A conspiracy newspaper tries to find an audience in Britain

On October 4, about a hundred people began filing into a community hall in Stroud, a pretty town in southern England that, like many of its peers, has a vein of disaffection and despondency running just under the surface.

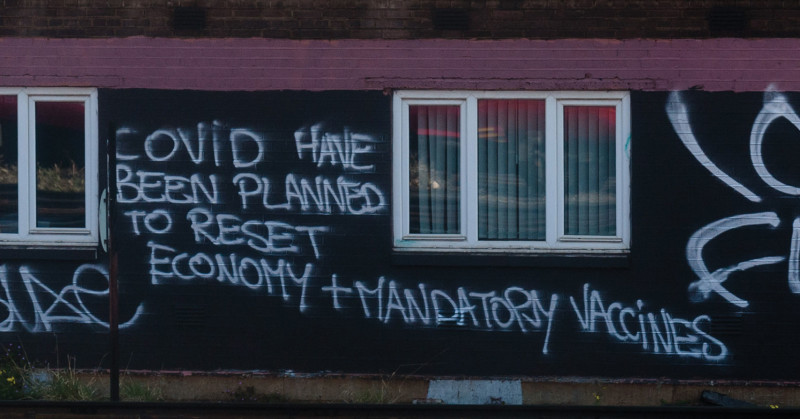

They were gathering to discuss the appearance of a new paper in the town called The Light. It is handed out in streets across the UK by volunteers; in some cases, stacks of copies are left in grocery stores. It offers readers a simple vision of reality: the world’s bad stuff, like COVID or war in Ukraine, can be explained by an elite cabal that is intent on pushing through a new world order.

Just like the Times, it has a bold logo in a commanding serif font, skyboxes that preview content, a splash, a large image. Headlines include “WHO wants to rule the world,” “Democracy a failed experiment,” “Jabs linked with seizures,” “How to stop 5G rollout,” and “Medicines can destroy health.” It says it provides “the uncensored truth”—throwing doubt on established narratives about war in Gaza, net-zero efforts, radiation poisoning, and more. Toward the back of its twenty-eight pages are the ads—privacy screens for laptops and phones, a holistic dental clinic (with a “focus on the natural healing abilities of the human body”), an ad for gold bullion that promises you can “be your own central bank.” Throughout, The Light wants its readers to get active. For the price of £190 ($237), you can buy five hundred copies. It urges: “Wake up your neighbours!”

Research from 2021 found that 25 percent of all articles were conspiracy-related. The Light has run stories by Nazi blogger Lasha Darkmoon (that elites brainwash people against questioning the Holocaust) and recommended a book by author Eustace Mullin (who also wrote Adolf Hitler: An Appreciation). BBC journalist Marianna Spring reported that the paper publishes as many as one hundred thousand copies monthly—costing almost $300,000 a year—and is distributed in thirty UK hubs, all funded by ads and subscribers. “That gives it perhaps a sheen of legitimacy that it wouldn’t have if it was just an online magazine,” David Lawrence, a researcher at anti-far-right-extremism charity HOPE Not Hate, told me.

The Light didn’t respond to an interview request from CJR. But Darren Smith (sometimes Darren Nesbitt), the founder and editor, was interviewed this year by the BBC in a pub near Manchester. “I’ve been awake for ten years,” he said. Smith said reading the paper “should be exciting to people, we don’t have to accept what the BBC tell us, we don’t have to accept what the official narrative is”—on topics such as “science, history, geography, cosmology, you name it, health, et cetera.”

The appeal of conspiracy theories, according to Rod Dacombe, director of the Centre for British Politics and Government at King’s College London, is that they offer psychological comfort in uncertain times, and that, like a game, they demand participation. QAnon “Q drops” asked followers to decode cryptic posts, inventing the mythology as they went along; The Light publishes puzzles and quizzes that tell readers to go and do your own research. One evening, Dacombe decided to follow along. He chose a crossword word-search game. “I found I was following another link and another link,” he told me. “The Light will not present information as finished. It will say, ‘Don’t take my word for it, go and look for yourself,’” allowing its readers to undergo a “process of revelation.” They become true believers all on their own.

The market for new sources is wide open. Just 40 percent of ninety-three thousand people surveyed globally said they mostly trusted the news, this year’s Oxford’s Reuters Institute Digital News Report found. Even if it doesn’t persuade people outright, Lawrence said, The Light and its twenty-thousand-strong Telegram channel make people think, “Maybe there is something in this.”

In 2020, around the time The Light came to be distributed in the town, people began to appear in Stroud’s town center to promote 9/11 and fluoridation hoaxes, or to express their support for the American conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, or their loathing for Anthony Fauci, who had been the face of America’s scientific response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “There is a strong theme of punishment and retribution throughout The Light,” Dacombe said. In June last year, the paper ran a story that read “under the 1947 Nuremberg Code, MPs, doctors and nurses can be hanged if found guilty of medical experimentation” with the COVID vaccine.

The event in Stroud was organized by a volunteer group, Community Solidarity Stroud District (CSSD), that had grown concerned about the popularity of the newspaper, and who equate it with the rise of fascism. The goal of CSSD is not to silence people involved with The Light, Denise Needleman, an organizer, said, but to “counter any arguments with good reason, argument, and evidence.” The event in Stroud was timed for the anniversary of a spontaneous uprising against fascism in Britain, on October 4, 1936, that is credited with humiliating the movement into submission as a mainstream force.

One of the speakers invited was the lawyer and historian of fascism David Renton. Watching over the packed room, about ten volunteer stewards from CSSD stood in yellow vests. But they’d allowed people associated with the paper to enter, to defuse tension. “The Light is, in the end, a far-right propaganda sheet,” Renton told the audience.

A few Light fans tried starting a debate—they mentioned 9/11, Needleman said—but found no receptive audience. They appeared embarrassed. And to Needleman’s eye, when she saw them handing the paper out in the following days, they looked “really quite glum.”

Jem Bartholomew is a freelance reporter. He was previously a Reporting Fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Jem’s writing has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, The Economist, Time, New York magazine, and others.