Why Tolkien and C.S. Lewis explored the flat-Earth “absurdity”

In January 1926, a new fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, gave his first lecture. It was standing room only, and he had to lead his audience into a larger room, so they could all sit down. This was the start of a career in which he educated generations of undergraduates. One course of his lectures, delivered many times at Oxford, was eventually published as The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature in 1964.

This don’s name was C. S. Lewis (1898–1963), who had died the previous year, celebrated for his Narnia series of children’s books, as a Christian apologist and an expert on late medieval English literature. In his academic work, Lewis fought back against the myth that medieval people thought the Earth was flat. As he wrote in The Discarded Image, ‘Physically considered, the Earth is a globe; all the authors of the high Middle Ages are agreed on this . . . The implications of a spherical Earth were fully grasped.’

However, when it came to creating his own world, Lewis found the Globe was not fit for his purposes. Narnia was flat. In the third Narnia novel, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, King Caspian leads an expedition across the Eastern Ocean to the end of the world. As the ship sails towards the dawn, the rising sun grows progressively larger, eventually becoming five or six times bigger. On the far side of the Ocean, the water is fresh and shallow, and covered with lilies. When the draught of the ship means it can go no further, a mouse, who is part of the crew, boards a tiny rowboat and paddles his way through a wall of water where he disappears. Beyond, the people on deck can just make out the high mountains of Aslan’s land, perhaps the earthly paradise of medieval legend.

The amount of commentary on C. S. Lewis, by both scholars and fans, is vast. Many have written about Narnia’s geography, but no one has given an adequate solution to why Lewis made it flat. After all, he was at pains to note in The Discarded Image that this was not how medieval people saw their world. Rather than over-analysing the issue, it seems likely we can find the answer in an exchange between King Caspian and a pair of English schoolboys called Edmund and Eustace, who have been magically transported to the [ship] Dawn Treader. Eustace thinks it ridiculous to say the world has an edge, but Edmund realizes that Narnia might be different to our own planet. Caspian is thrilled to learn about this:

‘Do you mean to say,’ asked Caspian, ‘that you three come from a round world (round like a ball) and you’ve never told me! It’s really too bad of you. Because we have fairy tales in which there are round worlds, and I’ve always loved them.

I never believed that there were any real ones . . . It must be exciting to live on a thing like a ball. Have you ever been to the parts where people walk about upside down?’

Edmund shook his head. ‘And it isn’t like that,’ he added. ‘There’s nothing particularly exciting about a round world when you are there.’

Lewis seemed to grasp how fantastical the theory of the Globe would be for someone who lived on a flat world – more like a myth than reality. But he also saw (this is a point he made many times) how inured to wonder we become once we take something for granted. Narnia was flat because it’s modelled on the mappa mundi, rich in Christian symbolism and different from the world revealed by science. But Lewis also wanted us to understand that it is possible to move between the symbolic and the real, if you know how. And from the inside, the symbolic world looks just as real as ours.

C.S. Lewis was not the only author to make his fantasy world flat. His friend J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973), another Oxford expert on medieval literature, did the same. The events in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit take place on a spherical earth. However, this had not always been the shape of the world. Thousands of years prior to the events in those books, evil men from the island of Númenor had attempted to invade the land of the elves in the far west. The dark lord Sauron had corrupted Númenóreans into believing that by doing so, they could obtain immortality. The elves prayed for deliverance. God, called Ilúvatar, uprooted the Undying Lands from the circle of the world, making it completely inaccessible to men. A great chasm opened up, which swallowed Númenor. Finally, the gods, authorized by Ilúvatar, ‘bent back the edges of Middle-earth, and . . . they made it into a globe, so that however far a man should sail he could never again reach the true West, but came back weary at last to the place of his beginning’.

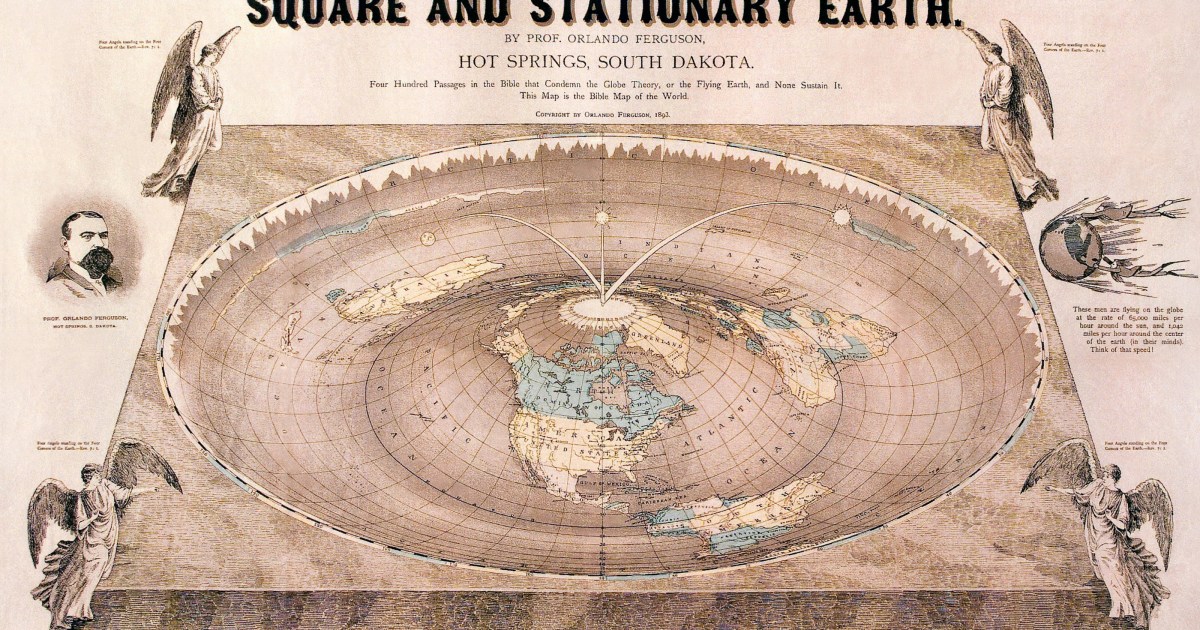

Tolkien’s academic speciality was Anglo-Saxon literature, and his particular passion was the Old English epic Beowulf. This story is set in a world that is a disc. In ‘The Monster and the Critics’, a lecture Tolkien gave on Beowulf in 1936, he noted that the poet ‘and his hearers were thinking of the eormengrund, the great Earth, ringed with garsecg, the shoreless sea, beneath the sky’s inaccessible roof’. He expanded on this point in his commentary on the poem, explaining that while educated people around AD 800 might well have been aware the Earth is round, this is not reflected in the verse and probably wasn’t part of the imaginative world of its hearers either.

England doesn’t have a fully developed mythology like the Greeks or Vikings. Perhaps it was lost or it never existed. Tolkien set out to create one. As this wasn’t a scholarly exercise, he was free to pilfer tropes from surviving stories in other related cultures, be they Irish sagas or French romances. For example, at the dawn of time, Tolkien wrote, the whole land was illuminated by two trees – an idea inspired by a passage from one of the medieval romances about Alexander the Great. When these trees were destroyed, fragments of their light formed the Sun and the Moon.

C. S. Lewis reveled in including absurdities in his tales (such as a lamp post in Narnia and an appearance by Father Christmas). Tolkien could not abide them.

According to Norse mythology – another influence on Tolkien – Yggdrasil, a great ash tree, stood at the centre of the world. In its roots, the worlds of men and giants were to be found. Even though they were great seafarers who briefly colonized North America, there was no room for the Globe in the Viking imagination. As late as the thirteenth century, the Icelandic chronicler Snorri Sturluson (1178–1241) began a history with the Old Norse words meaning the ‘the world disc’, which gives the saga its modern name Heimskringla.

The reason Tolkien made Middle-earth flat in its earliest incarnation may have been recognition that this is how all peoples once saw their world. The sundering of the Undying Lands and Middle-earth represented a loss of innocence that shut humanity off from the spiritual realm. Yet Tolkien came to regret this aspect of his mythos. In a lecture in 1939, ‘On Fairy-Stories’, Tolkien had discussed the importance of ‘secondary belief ’ and the rules that fantasy novels had to follow to achieve verisimilitude. He came to regard the flat Earth as failing the test because it was ‘astronomically absurd’. Unfortunately, it was too late to change such an integral part of the story of the Silmarillion, which might be why he never completed it. C. S. Lewis reveled in including absurdities in his tales (such as a lamp post in Narnia and an appearance by Father Christmas). Tolkien could not abide them.

In this article