In elections we trust not, say many Americans

Voters filling out ballots for early voting in the 2024 presidential election in Chicago, Illinois, on Oct 4.

PHOTO: AFP

WASHINGTON – In what could be called the “bamboo hoax” of the 2020 presidential election, auditors in Arizona scanned thousands of ballot papers for evidence that these had been pre-filled, stuffed in boxes and shipped from China to secure a Joe Biden win.

The claim, based on the alleged presence of bamboo fibre as proof of Chinese interference, was made by pro-Trump conspiracy theorists. No fraud was uncovered, but the sentiment it fed is rampant today, with the election less than 30 days away.

Distrust, deepened by rhetoric that is austerely dubbed as “divisive” by the media, is stoking a crisis of confidence in the country’s imposing yet curiously fragile election infrastructure.

Like in 2016, a stressor this time is the presence of an estimated 11 million illegal immigrants. Unlike then, illegal immigration has leapt from the sidelines to the main stage in 2024. It is the top issue after inflation.

The Trump campaign claims that some of these non-citizens will attempt to vote and sway the election in favour of Democratic candidate Kamala Harris.

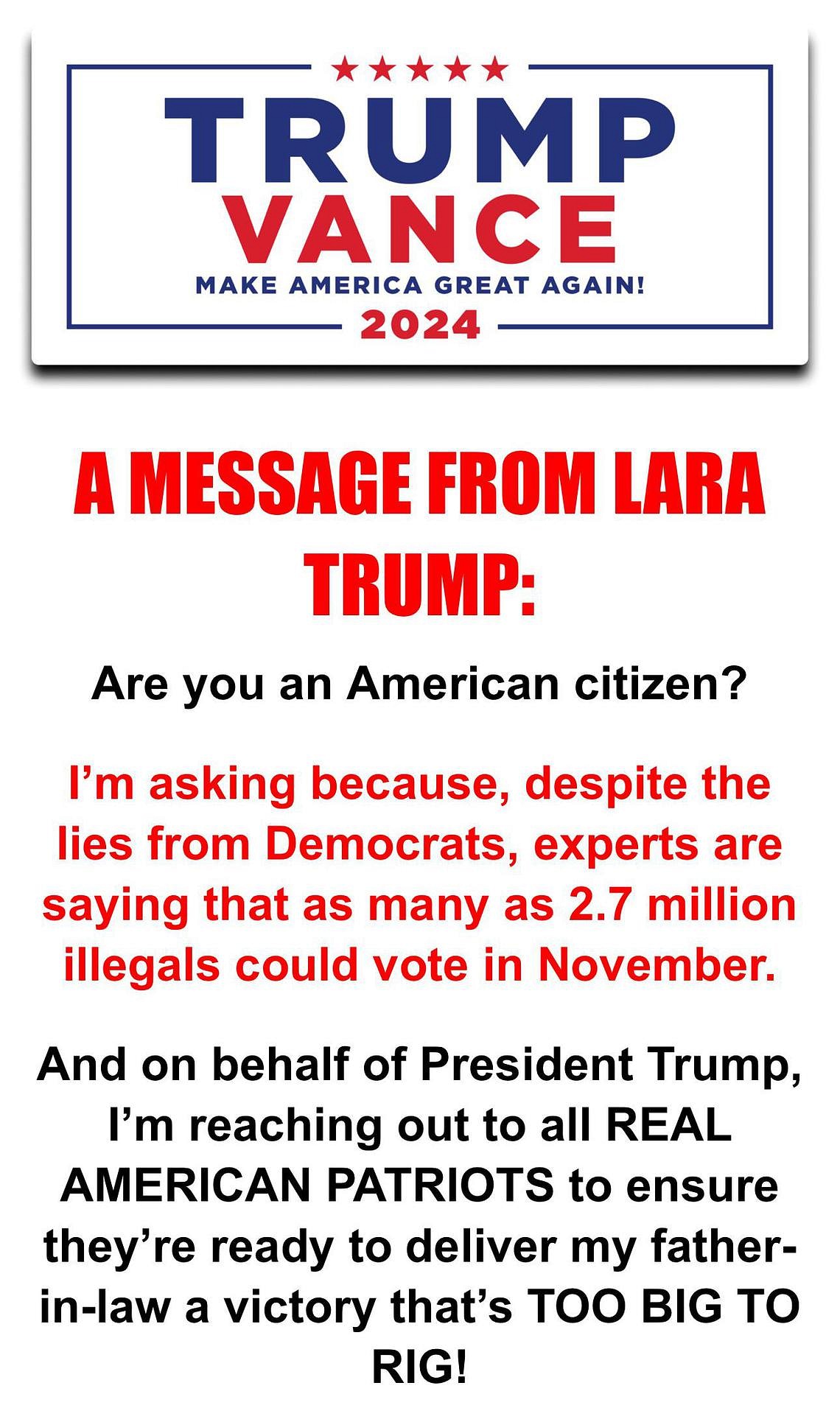

Republican National Committee (RNC) co-chair Lara Trump sent out a text message on Oct 10 warning of illegal voting. Her pitch for donations dovetailed into a plea to Republicans to turn out in large numbers to ensure – in her words – that the victory is “too big to rig”.

Experts on the electoral system argue that the idea is far-fetched.

“I don’t think there’s evidence that voting by non-citizens is a large problem,” Dr John Fortier, an expert on election administration at the American Enterprise Institute, told The Straits Times.

“But I will say that our voter registration lists are not perfectly clean,” he added. “People sometimes get on the list as non-citizens.”

Republican National Committee co-chair Lara Trump sent out a text message on Oct 10 warning of illegal voting. ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

No one can say how many. This uncertainty stems partly from the country’s sprawling, decentralised election system, a patchwork of state-run operations that do not always communicate seamlessly.

“We have 50 states and they don’t all talk to each other. So we don’t have a perfect view to know exactly what and how that’s happening,” Dr Fortier said.

It is hard to obtain figures of what exactly is needed to hold the election, in manpower or money. Estimates put the number of election workers deployed in the 2020 election at between 774,000 and one million, and the cost ranging from US$4 billion (S$5.2 billion) to US$10 billion.

While no state Constitution allows non-citizens to vote, some municipalities in California, Maryland, Vermont and the District of Columbia do permit voting by non-citizens in some local elections, such as for school board and city council.

But there do not seem to be enough non-citizens to turn the scales. Republican-led states have conducted voter roll reviews, with Texas removing more than 6,500 potential non-citizens since 2021. That number pales in comparison with the state’s nearly 18 million registered voters.

House Speaker Mike Johnson supports requiring proof of citizenship to register. However, implementing such measures could prove challenging in a country lacking a national birth registry, where less than half of its citizens hold passports.

Public opinion polls reflect a sense of tentativeness in the public mood: A recent Gallup poll found only 57 per cent of respondents had faith that votes would be accurately cast and counted.

The partisan divide between those who believe the system works and those who do not is stark – just 28 per cent of Republicans and as many as 84 per cent of Democrats.

Another worry ahead of the election is how the under-funded election apparatus will hold up under unprecedented public scrutiny and, possibly, harassment. The Trump campaign has reportedly been training and mobilising 100,000 supporters, according to the RNC, to act as “election integrity” advocates in swing states.

However, Dr Fortier saw reason for optimism, citing improved voter registration systems and the adoption of voting technologies that engender trust. Amid suspicion of fully electronic voting systems, most US voters still vote by paper ballots or systems that produce a paper record.

Perhaps the biggest worry is how readily, if at all, the verdict is accepted, and if losers will engage in frivolous and bad-faith challenges to results.

Trump has been quoted by the media as saying he would not accept a loss. He has not retracted the claim that the 2020 election was rigged, even after numerous court challenges failed.

His supporters believe he was a victim of election fraud. False theories circulated that then Vice-President Mike Pence had unilateral authority to reject electoral votes from contested states.

These, and several other conspiracy theories that the Trump base embraced, led to a violent attack on the US Capitol when lawmakers were meeting to certify the results, leaving four dead and 140 law enforcement officers injured.

Will a close election, razor-thin margins and deep mutual mistrust cause a repeat of a Jan 6 type of situation?

To be sure, the 2020 election was highly unusual in that it was held during the Covid-19 pandemic, when it was unclear if in-person voting was safe. Public opinion was divided on whether mail-in ballots should be allowed and how they should be counted, Dr Fortier noted.

“This is still an intense election, but the odds of somebody using the Electoral College machinery in crazy ways is less than it was in 2020,” he said.

What certainly does not help is the great distrust for mainstream media; only around a third of Americans trust the media to report the news in a full, fair and accurate way.

About half find it difficult to tell fact from fiction when getting news about the election, according to a new Pew Research Centre survey.

Coincidentally, the survey came out on the day Trump criticised one of America’s big TV networks, claiming it had manipulated Democratic candidate Kamala Harris’ answers in an interview to make her look better.

In response, the CBS network said different portions of her answers were used on its 60 Minutes and Face The Nation programmes. Noting that this was standard editing practice, the network added that it had used similar approaches for Trump’s past interviews.

The coming election, thus, is not just a test of who wins the White House, but also whether the American experiment – the system of self-governance conceived at the time of America’s founding, which is seen as a work in progress – emerges stronger after its 60th presidential election.