From delayed results to voter intimidation — 6 things that could go wrong on election night

U.S. election security officials have said the 2020 election was “the most secure in American history,” and a months-long analysis by the Associated Press found fewer than 475 cases of potential voter fraud in the six key battleground states — despite former President Donald Trump’s baseless claims of a “rigged” result.

But the extraordinary closeness of the latest polling in the 2024 race between Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris — and Trump’s continued insistence that the “only way” he can lose again is if Democrats “cheat” — means that Election Day could be as chaotic and confusing in 2024 as it was four years ago. Here are six key things that could go wrong on Tuesday:

Slow counting in key states

According to the latest surveys, the battleground states of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are likely to be two of the closest in terms of the final results. And in both of those states, workers are not allowed to start counting early ballots until Election Day.

In most states, early ballots are opened and processed (i.e., “pre-canvassed”) as soon as they arrive — or, at the latest, in the week before the election. That’s the main reason state officials can report their results so quickly after the polls close.

But that’s not how Pennsylvania and Wisconsin operate. There, it’s extremely unlikely that either Harris or Trump will jump out to the sort of immediate, clear-cut lead that enables media outlets to project and ultimately declare a winner with only a small percentage of precincts reporting. So the counting could continue well into the next day or even into the next few days, depending on how narrow the margins are.

If that happens, the entire election could hang in the balance.

Confusion over the rules — and challenges to the results

The longer it takes to call a winner — and the closer the eventual outcome is — the more chaotic things could get. Pennsylvania in particular is looking problematic.

Generally, states have rules governing the counting of mail ballots that apply throughout the state and can be used to resolve disputes. But Pennsylvania has 67 different partisan county boards with different rules about which mail ballots they’ll accept, how and when they’ll notify voters about mistakes, and even whether they’ll allow voters to fix the mistakes they’ve made.

This is a recipe for disaster. In the Bush v. Gore ruling following the 2000 election, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Florida’s use of different vote-counting standards within the same state. So if the winning margin in Pennsylvania is tight (it was about 44,000 in 2016) and if the usual number of ballots are rejected (it was about 34,000 in 2020), local decisions about mail ballots will almost certainly wind up in court.

In fact, any razor-thin result — in Pennsylvania or elsewhere — is likely to trigger litigation. Since Jan. 1, 2021, the GOP and other Trump-aligned groups have already sued more than 50 times across the seven key battleground states. Claiming to be acting against voter fraud, Republicans have sued to purge voter rolls; bolster signature and ID requirements; reduce the use of ballot drop boxes; and require that all ballots be counted by hand.

The party’s goal, as voting rights expert Danielle Lang of the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center recently told NBC News, is to “create confusion and chaos” — and to use that confusion and chaos as a pretext for post-election challenges.

“A lot of this litigation is, quite frankly, not designed to succeed,” Lang explained.

Democrats have also filed lawsuits. According to NBC News, they have mostly focused on “expanding voting access by trying to extend registration deadlines or appealing for broader interpretations of laws about absentee ballots and voter identification.”

The Trump factor

In 2020, Trump claimed long before the election that the only way he could lose was if it was “rigged.” Then, when he did lose, he continued to publicly push this falsehood while privately overseeing a scheme to overturn his loss.

Unless Trump secures a cut-and-dried victory on Election Night, he will almost certainly try to do the same thing again. “They are getting ready to CHEAT!” he wrote in a Sept. 23 Truth Social post. At the same time, he has repeatedly sidestepped questions about whether he will commit to the peaceful transfer of power.

So if Pennsylvania or any other state is too close to call on Nov. 5 — and if its initial, incomplete vote count shows Trump ahead of Harris while Democratic-leaning mail ballots are still being processed — Trump is expected to once again declare himself the winner, regardless of what the full tally ultimately shows.

From there, according to reporting from Politico and others, Trump and his allies would likely lean on partisan election officials in contested states to refuse to certify the results (presumably by citing the partisan lawsuits mentioned above). Since 2020, 35 of these battleground-state officials have already done just that — even though they lack the necessary authority.

Short of prevailing in close races in battleground states, the former president and his allies are unlikely to get as far as they did in 2020, thanks to recently passed bipartisan laws blocking efforts by bad actors to meddle with the results. But just 28% of Republicans now have confidence in the accuracy of U.S. elections, according to Gallup, down from 55% in 2016 — so it won’t take much to divide and disrupt the country.

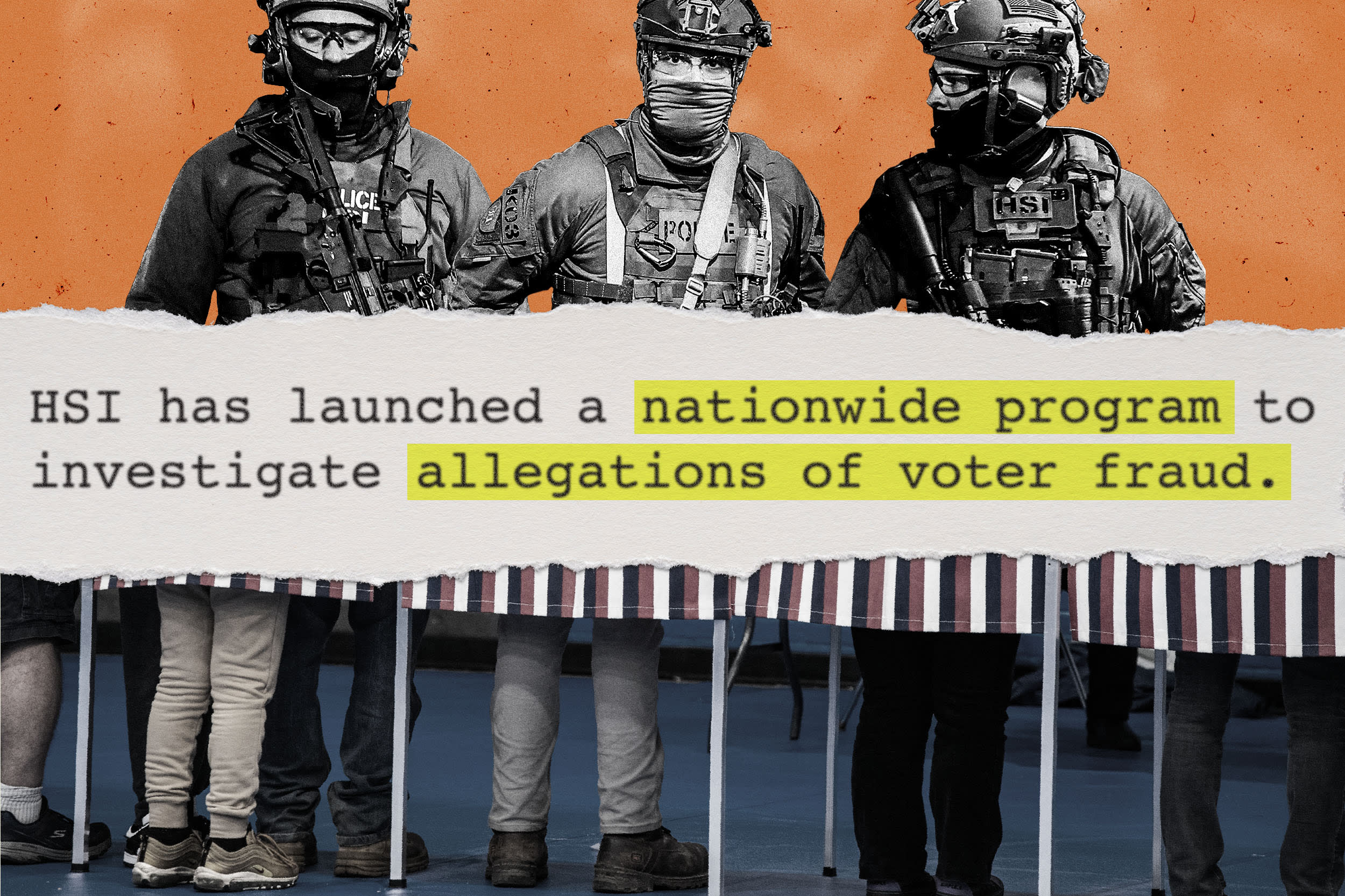

Violence or intimidation at polling places

Driven by the former president’s personal obsession with “election integrity,” the Trump campaign has reportedly recruited a network of more than 150,000 volunteer poll watchers and poll workers “to go into the polls and watch very carefully,” as the candidate himself recently put it.

“We need every able-bodied man, woman to join [the] Army for Trump’s election security operation,” Donald Trump Jr. said in an online video. “We need you to help us watch them. Not just on Election Day, but also during early voting and at the counting boards. President Trump is going to win. Don’t let them steal it.”

The concern among voting rights advocates, election officials and Democrats is that if such an “Army” does materialize outside or inside polling places, legal observation could tip over into illegal intimidation — which could discourage or deter people from voting.

Even violence is a possibility, including confrontations that shut down polling places or ballot-counting facilities. According to the New York Times, “federal officials have not released data on the volume of violent threats and incidents of intimidation reported by local governments, but experts say it has increased substantially since the summer.”

Last week alone, the Justice Department unsealed a complaint against a man in Philadelphia who had vowed to skin alive and kill a party official who was recruiting volunteer poll watchers. The police in Tempe, Ariz., arrested a man in connection with shootings at a Democratic campaign office. Prosecutors charged a 61-year-old man from Tampa, Fla., with threatening an election official. A blue U.S. Postal Service mailbox in Phoenix was set on fire, damaging about 20 ballots. (The suspect admitted to committing arson but claimed his actions were not related to the election.) And on Monday, drop boxes in Oregon containing hundreds of ballots were also targeted by arson.

Cyberattacks

This year, 98% of voters — including every single voter in the battleground states — will cast paper ballots. So the chance of electronic vote-tampering is minuscule. But a cyberattack could still affect, say, the election-night reporting system that media outlets rely on. And “foreign disinformation about the reliability of the vote is even more pervasive in 2024 than it was in the past several election cycles,” according to Time, with Russia, China and Iran acting online to further divide Americans over the election results. They “make us hate one another so much that we internally tear ourselves apart or we make enemies out of ourselves,” Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes told the magazine.

Bad weather

Hurricane Helene has already upended the election in North Carolina, where the General Assembly unanimously passed special voting rules after the disaster to make it easier for 1.3 million registered voters in 25 storm-ravaged counties to vote in person and by mail. Any new weather emergency has the potential to shutter polling places or disrupt turnout.