Fluoridation of community water and the politics of disinformation

The first part of this review was published December 7 and can be accessed here.

Fluoride and dental caries

Fluorine is the 13th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, present almost entirely in the form of fluoride, held in mineral deposits. It is naturally present in ground and seawater sources. The natural weathering of rocks releases these fluorides into the ecosystems through a process known as the fluorine cycle. While levels in seawater range narrowly from 0.86 to 1.4 mg/L, concentrations in rivers and freshwater lakes can vary considerably from 0.05 mg/L in parts of Canada to around 8 mg/L in parts of China. (1 mg/L—1 milligram per liter of water—is the same as 1 ppm, or one part per million, since a liter of water weighs one kilogram, or a million milligrams.)

Fluoride is certainly not the only element or mineral in drinking water. Others include sodium (20 mg/L), chlorine (4 mg/L: important to disinfect water), calcium (20-30 mg/L), iodine (4 ug/L), iron (0.3 mg/L), zinc (5 mg/L), and magnesium (10 mg/L), which are important for individual health within certain limits.

For fluoride, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set the upper-limit at 1.5 mg/L, while in the US the official recommendation is a concentration of 0.7 mg/L of fluoride, striking a balance between the dental benefits of fluoridation without undue exposure to higher levels that can lead to teeth staining and or, with very high concentrations and prolonged ingestion, skeletal fluorosis (a disabling condition where the bones become hardened and less elastic, therefore fracture prone) endemic in regions of the two most populous countries, China and India.

Globally, around 25 countries add fluoride to drinking water to varying degrees; 11 countries provide fluoridated water to more than half their population. There are 28 countries with naturally fluoridated water, although in many of them the fluoride is above the recommended safe level.

More than 400 million people worldwide receive water fluoridated at the recommended level, nearly half of those in the United States. Almost three-quarters of the US population is served by community water systems that have fluoridated water. Less than one percent of the population (under three million people) use water with natural fluoride levels exceeding 1.5 mg/L.

The fluoridation of drinking water, historically, has led to a reduction in cavities among children by more than 60 percent. Fluoride prevents dental caries through topical-remineralization of tooth surfaces. Presently, at current levels, the reduction is in a range of 12 to 42 percent, and substantially benefits people living in poor communities where 40 to 70 percent of their fluoride intake comes from drinking water.

Caries of permanent teeth are one of the most prevalent conditions, affecting some 2.4 billion people. This includes nearly 500 million children suffering from caries of their primary teeth. The WHO declares:

Public health actions are needed to provide sufficient fluoride intake in areas where this is lacking so as to minimize tooth decay. This can be done through drinking-water fluoridation or, when this is not possible, through salt or milk fluoridation or use of dental care products containing fluoride, and by advocating a low-sugar diet.

An American Fluoridation Society economic analysis found that for most cities, every $1 investment in water fluoridation saved $38 in dental treatment costs. A 2010 New York state study found that Medicaid enrollees in less-fluoridated counties required 33 percent more fillings, root canals, and extractions than those in counties where fluoridated water was much more prevalent. Scientists testifying before Congress in 1995 estimated that fluoridation led to annual savings of $3.84 billion. These are but some of the numerous findings on the economic gains associated with fluoridation.

Tooth decay remains the most common chronic disease of childhood in the US. About one in four children living below the federal poverty level have untreated tooth decay that leads to pain, missed school days, and poorer school performance.

With respect to health concerns raised about fluoride, the public health services addressed these in a comprehensive review published in 2005. On the topic of fluoride and bone cancer, when actual bone fluoride concentrations were measured, there was no association between fluoride levels and the bone cancer. These findings were consistent with ecological studies. Animal studies did not support classifying fluoride as a carcinogen.

Returning to the topic of IQ and neurological effects, an earlier National Regulatory Commission (NRC) review of several Chinese studies where the mean fluoride concentrations were in the range of 2.5 to 4.1 mg/L, several times higher than recommended, noted reports of a lower IQ among children exposed to these levels. In that review, the NRC found the significance of these findings was uncertain due to important procedural details having been omitted. Earlier meta-analysis suffered from similar poor-quality studies leading to conclusions by a critical review in 2011 conducted by the Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER) that “a biological plausibility for the link between fluoridated water and IQ has not been established.”

The impact of fluoride on the endocrine systems—the thyroid, parathyroid, and pineal glands—especially in the young has been reviewed in studies of both animals and humans. These too suffer from similar limitations noted above, but no link has been found despite assertions by the anti-fluoridation advocates.

It is no exaggeration to say that hundreds of reports on fluoride and drinking water are published in numerous journals every year. A PUBMED search resulted in 14,272 listings on the topic since 1934. The topic has been well studied and understood. The sudden eruption of the controversy on fluoridation of drinking water is not one of scientific uncertainty but a political contrivance by right-wing groups that has persisted and festered on the fringes of society until recently, especially in the wake of the COVID pandemic.

The discovery of the benefits of fluoridation

The discovery of fluoride and its benefits on dental health began in 1901. A young dentist named Frederick McKay, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, had recently opened a practice in Colorado Springs. There he noticed many of his patients had permanent discoloration of their teeth known as “Colorado Stain.”

Intrigued, he enlisted the assistance of a renowned dental researcher, Dr. G. V. Black. They found that more than 90 percent of the locally born children suffered from the stain, termed initially “tooth mottling” (later changed to “fluorosis,” a condition caused by high fluoride levels in drinking water). McKay also noted that these children’s teeth were resistant to decay. He believed that the answer must be in the water sources, but he had not yet identified the actual cause.

In 1923, McKay went to Oakley, Idaho to investigate an uptick of tooth mottling. Speaking to parents, they told him that the stains began to appear only after the town had constructed a communal water pipeline to a nearby spring a few miles away. McKay instructed the town to use another source for water. Within a few years, the brown stains disappeared, but McKay was no closer to figuring out why.

It wasn’t until 1930 in Bauxite, Arkansas that McKay, with the assistance of H. V. Churchill, chief chemist for the Aluminum Corporation of America (Alcoa), finally pieced the puzzle together. During his investigation there, he discovered that those born after 1909 had badly stained teeth and those before 1909 did not. Bauxite had changed its water supply that year.

He published his findings, which caught the attention of Alcoa, Bauxite’s largest employer, which at the time was dealing with a public relations crisis concerning its aluminum cookware and the charge that aluminum was poisonous. Concerned that aluminum would be blamed for the teeth staining in Bauxite, the company tested the water from the new wells, but this time using more sophisticated technology, and found high levels of fluoride at 13.7 parts per million (ppm). Churchill informed McKay of his findings.

In the meantime, a husband-and-wife research team from the University of Arizona, H. V. and Margaret Cammack Smith, had reached similar conclusions about fluoride in drinking water.

These findings finally prompted the US Public Health Services, led by Dr. H. Trendley Dean from the San Francisco office, to conduct additional investigations to confirm the results obtained by McKay/Churchill and the Smiths. A comprehensive national analysis confirmed these findings and found that mottling and discoloration of teeth, now called dental fluorosis, began when fluoride levels in water exceeded 1 ppm.

However, Dean also recognized that children from regions where water fluoride concentrations were higher also had a lower incidence of dental cavities compared to regions with low fluoride levels in drinking water. In 1938, Dean and his colleagues established this level, about 1 ppm, as safe and effective in reducing tooth decay and avoiding mottling and discoloration.

Dean hypothesized that adding this level of fluoride to community water could help fight tooth decay while maintaining cosmetically safe levels. His 1942 study of 21 cities found that people living in areas where community water supplies contained fluoride had fewer cavities and less severe decay. This led the Public Health Service, near the end of the Second World War, to launch a long-term social program to assess the safety and benefit of adding fluoride to public water. Grand Rapids, Michigan was selected as the test city to address these questions.

The residents there were the first residents in the country to begin drinking fluoridated water with the control arm of this experiment at nearby Muskegon, which did not fluoridate. Both cities provided consent to the 15-year experiment with investigators anxiously hoping their efforts would bear fruit. The project was an immense success. Notably, the reduction in tooth decay in the first five years was considerable. The study ended just after six years, with Muskegon officials demanding fluoride for their drinking water. After just 11 years, among 30,000 schoolchildren in Grand Rapids, Dean observed the rates of cavities had dropped 60 percent among children born after fluoride was introduced.

Political controversies over fluoridation

These early reports led John Frisch, Wisconsin’s dental health officer, to call for the fluoridation of the state’s water supply. Frisch, a progressive, was an avid promoter of fluoridation, as well as other public health measures, including regulating utilities and railroads, bringing tuberculosis under control, food inspection, and the creation of a powerful state board of health. However, it was his call for immediate action on fluoridation that set the political stage for the ensuing anti-fluoride campaign that ignited in that state. There was enthusiasm for fluoridation among one layer, but skeptics in another, especially in the red scare climate so prevalent after World War Two and emergence of Joseph McCarthy.

As Donald R. McNeil wrote on the fight for fluoridation in Readings in American Health Care (1995):

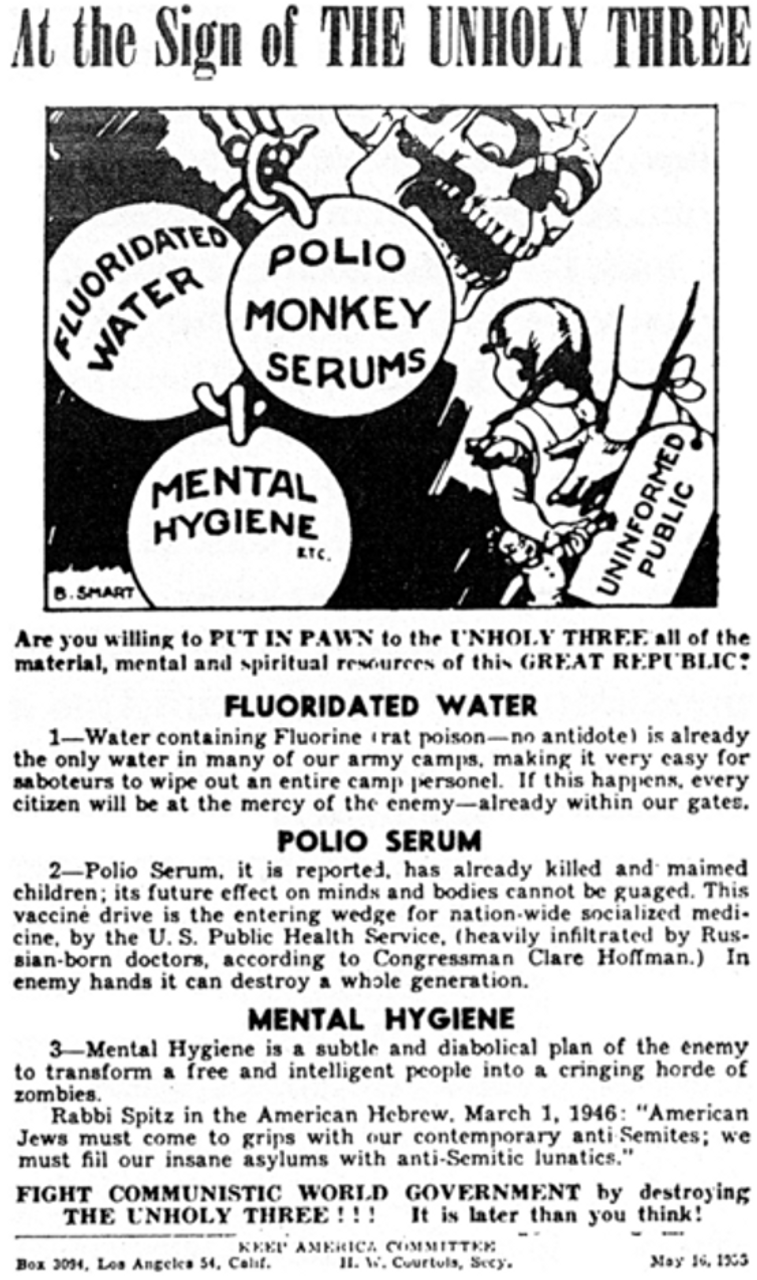

In fact, resistance had begun to form even before the big health organizations put their imprimatur on fluoridation. In Stevens Point, Wisconsin—one of the towns where Frisch campaigned—the backlash was led by Alexander Y. Wallace, a self-styled “watchdog of the public treasury,” local poet, and frequent writer of letters to the editor. His argument: Fluoride was “poison.”

Indeed, Wallace’s efforts to paint Frisch and his team’s fluoride expertise as outsiders looking to experiment on and infringe upon the liberties of Stevens Point citizens won him a referendum that rejected fluoridation in September 1950 and left the pro-fluoridation health officials and scientists dumbstruck. The Stevens Point episode also provided those opposed to fluoridation a strategy to sow doubt in the constituents, using scaremongering, with terms like “rat poison” and “guinea pigs.” They questioned the intentions of government scientists and appealed to Cold-War paranoia, using anti-communist rhetoric.

McNeil wrote:

Wallace’s triumph at Stevens Point, well publicized by the national press, soon acquired a folkloric status among the opponents of fluoridation. It was their Battle of Bunker Hill, and it demonstrated not only that fluoridation was a political issue but also that a well-orchestrated campaign could defeat the experts.

He added:

Before Stevens Point, there was no organized opposition to fluoridation. There were only scattered cries of alarm from people who (like Wallace) had earlier opposed the pasteurization of milk and other government-imposed health measures.

Now, however, national networks began to form. Individuals, including some dentists, chiropractors, natural health advocates, and ordinary “concerned citizens,” found allies in such diverse organizations and publications as the John Birch Society, the Ku Klux Klan, the Citizens Medical Reference Bureau (a long-time fighter of immunization), Prevention magazine, and the Medical-Dental Ad Hoc Committee on the Evaluation of Fluoridation. These groups and individuals began sharing information, offering suggestions on tactics, and in other ways (sometimes financial) providing mutual support.

In the wake of these developments there emerged a disinformation movement claiming that fluoride was a cancer-causing agent or linked to a variety of illnesses, without a shred of evidence to support the allegations. Furthermore, the proponents characterized fluoridation as a form of forced experimentation on humans being conducted by “godless medical technocrats.”

Although the initial opposition dwindled, the question of fluoridation had grown into a social and political issue used opportunistically by these libertarian zealots to promote an anti-communist agenda. In alliance with Christian Scientists, they claimed that people were being subjected to forced “mass medication.” There were lawsuits, but by 1961 the Supreme Court had ruled that fluoride was a trace element already found in foods and water. Furthermore, it was only added to water supplies when concentrations were deemed too low to prevent cavities. Fluoridation was upheld, but this only entrenched the reaction against it.

The first voicing of an anticommunist perspective on fluoridation, McNeil notes, began in the 1950s with a San Francisco housewife by the name of Golda Franzen, who called fluoridation a “Red conspiracy.” McNeil wrote:

She predicted that fluoridation would produce “moronic, atheistic slaves,” who would end up “praying to the Communists.” Franzen’s warnings, echoed by such groups as the John Birch Society and the Ku Klux Klan, acquired particular salience during the anti-communist fevers of the McCarthy era. For his part, C. Leon de Aryan, editor of an anti-Semitic publication in San Diego, described the spread of fluoridation as a plot to “weaken the Aryan race” by “paralyzing the functions of the frontal lobes.”

The anti-fluoridation campaign was seized on by an ultra-right fringe for whom issues of science and facts were of little concern. They made claims of deleterious effects of fluoride irrespective of anything grounded in objective fact. The conspiracy theory peddled by the John Birch Society, that fluoridation was a communist plot to enslave the population, was widely ridiculed.

This popular sentiment was cogently expressed in the portrayal of Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper, one of the main nuclear war plotters in the 1964 satire by director Stanley Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove. In one scene, amid a base lockdown after having ordered his bombers to drop nukes on the Soviets, General Ripper explains his actions to his bewildered subordinate. “I can no longer sit back,” he says with cigar in hand, “and allow Communist infiltration, Communist indoctrination, Communist subversion, and the international Communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids.”

Science and the working-class movement

Fundamentally, scientific discoveries and their practical application in numerous fields for the betterment of society are the end products of the advancements made by the working class movement. The 1917 Russian Revolution ensured the establishment of universal free health care systems, which saw life expectancy soar. Notwithstanding the world wars and betrayals of Stalinism and rise of fascism, the impetus towards progress and the application of the sciences drew inspiration from the victory of the proletariat in Russia led by Lenin and Trotsky. In a manner of speaking, the entire modern history of humanity has seen the concordant development of scientific progress with the gains made by the working class in its struggles.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the associated transformation of the mass working class organizations in the capitalist countries into openly capitalist parties and “unions” that operate as industrial police forces against the working class have been essential factors in the regression in popular support for science against religion, and in conspiracy theories that resemble primitive superstitions.

David North, national chairman of the Socialist Equality Party (US) and chairman of the international editorial board of the World Socialist Web Site, gave important expression to this connection in a critical essay in 2005 on the controversy over the case of Terri Schiavo, a woman who had been kept alive despite being declared brain dead for 15 years. North said in his opening paragraph: “The controversy surrounding the fate of this unfortunate woman and her beleaguered husband is a prism through which the malignant social contradictions of the United States are being refracted,” with the personal tragedy of a single family reflecting the “ugly truths about the society in which the event is unfolding.”

He added:

Of course, fundamentalist demagogy and charlatanry are hardly new phenomena in the United States. But never before have the national government and the ruling political party embraced American-style Christian fundamentalism as their ideology and sought to develop out of a wide network of reactionary fundamentalist organizations a mass political constituency.

In addition to the rise of quackery and anti-scientific sentiments, North addressed the rising influence of religion in American life, which he attributed to the collapse of the American labor movement since 1980. He wrote:

The victim of their own political bankruptcy and cowardice in the face of the offensive launched by the corporations, with the backing of the government, against the working class in the early 1980s, the trade unions have more or less disappeared as a significant social force in the United States.

He added:

The virtual disappearance of what had been the principal form of mass organization and popular resistance to corporate power radically changed the nature of the relationship between workers and the economic structure within which they live. Whereas in the past they confronted this structure, however inadequately, as a class, they now confront this structure as isolated individuals. They find themselves in a situation where they are compelled to confront problems not as part of a social collective, but by themselves.

Religion serves to fill the great social void in the lives of workers. Unable to fight for their interests as part of a class movement, workers believe that they must fight on their own. Hence the importance of having Jesus “in one’s corner,” to tend to life’s bruises and whisper encouragement.

North concluded his analysis by drawing out the essential connection between scientific knowledge and the struggles of the working class:

We can draw great encouragement from the fact that science is providing the socialist movement with a vast new array of intellectual weapons. It is ironic that the field of science at the very center of the Terri Schiavo controversy—neurobiology—is the scene today of the most spectacular theoretical breakthroughs. Astonishing advances are being made in the understanding of the physiology of the brain, the most complex of all material structures. And these, in turn, substantiate the materialist understanding of consciousness and cognition championed by Marxism. It is no wonder that the ruling elite should so fear the work of the finest scientists, whose discoveries in the field of neurobiology and related areas of research are systematically demolishing the last redoubts of religious mysticism.

The working class cannot advance without the aid of science. But science itself requires the advance of the working class. Today, the growth of political reaction in the United States places the scientific researcher under siege. But the isolated scientist cannot defend him- or herself any more successfully than the individual worker. In the final analysis, the progress of science as a whole, not to mention the physical safety of individual researchers, depends on the resurgence of a new revolutionary movement of the working class. In the most profound historical sense, the socialist movement unites under its banner both the pursuit of scientific truth in all its forms and the struggle for human equality.

The evisceration of mass organization, explained by North, has also made the population susceptible to these bald lies packaged in populist rhetoric. Clearly, the repeated lies by the public health officials downplaying the dangers of COVID have strengthened the hand of reaction. Just as there is no constituency in the ruling class for the defense of democratic rights—as demonstrated by the 2000 Supreme Court decision in Bush v. Gore—there is no constituency for the defense of science when its findings threaten the profit interests of the financial aristocracy.

And now, with Trump’s ascension and RFK Jr. at the helm of the Department of Health and Human Services, science is falling prey to the same reaction that has seen conditions of working people deteriorate. These will certainly fuel the assault on their living conditions and standards and propel the resurgence of the revolutionary movement. But this will require that scientists and health care researchers unite in solidarity with workers on an international basis.

Concluded

margin: 0 auto;

white-space: normal;

-webkit-user-modify: read-only;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form {

font-size: 13px;

line-height: 1.2em;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form h3 {

height: auto;

font-size: 24px;

color: #000;

line-height: 1.1em;

background: none;

padding: 0;

margin-top: 0;

}

#form .mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-checkboxgrp-row {

display: flex;

margin: 8px 0 8px 0;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-checkboxgrp-label {

width: 100%;

font-size: 1rem;

line-height: 1.5em;

color: #393C43;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-checkboxgrp-checkbox {

width: 1.5rem;

height: 1.5rem;

font-size: 1rem;

accent-color: #EC143B;

margin: 0 12px 0 0;

transform: scale(1.0);

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-button-wrapper {

margin-bottom: 0;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-button-wrapper .mauticform-button.btn-default {

width: 100%;

color: #fff;

padding: 16px 24px;

background: #CC0000;

border: #cCC0000;

font-size: 1rem;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-label {

font-size: 1rem;

display: block;

font-weight: bold;

margin-bottom: 8px;

color: #050404;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-input,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-selectbox,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-textarea {

font-size: 1rem;

padding: 8px;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-input,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-selectbox {

height: 40px;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-message {

font-size: 1.125rem;

line-height: 1.5em;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-errormsg {

font-size: 1rem;

margin-top: 8px;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 48em) {

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-checkboxgrp-label {

font-size: 1.125rem;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-button-wrapper .mauticform-button.btn-default {

font-size: 1.125rem;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-input,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-selectbox,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-textarea {

padding: 14px;

}

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-input,

.mauticform_wrapper > form .mauticform-selectbox {

height: 48px;

}

}