UFO Sightings Are Putting Airline Pilots in Danger—But Scientists Have Designed a Groundbreaking Solution

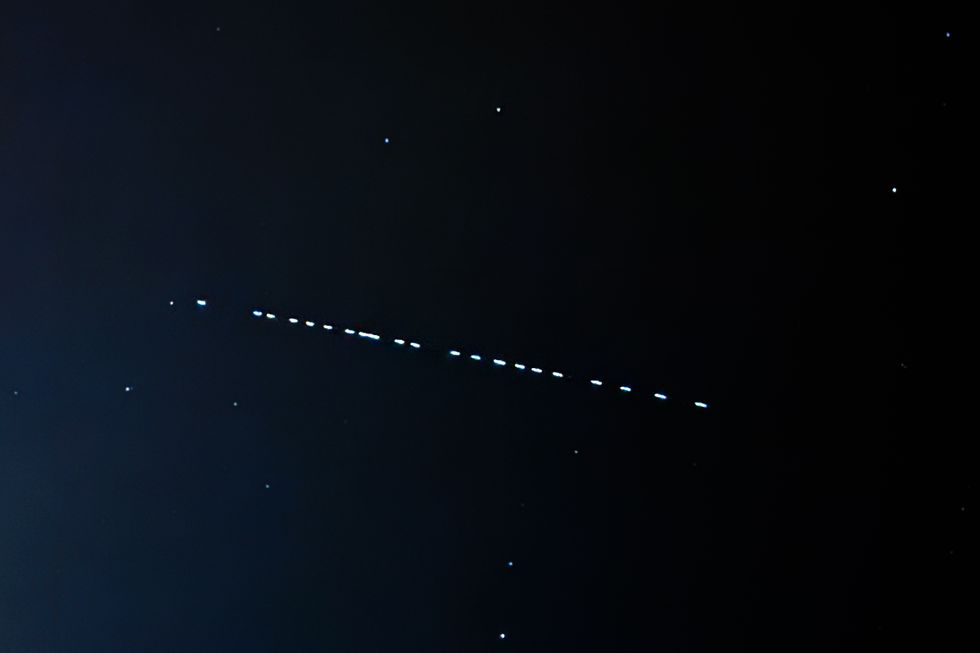

On the night of August 10, 2022, five pilots on two separate commercial airline flights were wholly convinced they’d documented proof of an Unidentified Anomalous Phenomenon (UAP) over the Pacific Ocean. Pilots from both flights reported seeing odd lights zipping through the sky—but the single incident they all witnessed turned out to be Starlink telecommunications satellites.

In recent years, pilots—as well as the public—have mistakenly identified these low-Earth orbit satellites as UAPs. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration released a list of 69 reports just from January 23–April 27, 2023 that identify “UFO-UAP,” and according to one paper, more than a third of them could be Starlink satellites. Unfortunately, such mysterious sightings lead to pilot confusion and potential safety consequences because of the distraction and extra chatter about them over the airwaves.

The core issue with pilots misidentifying satellites as UAPs stems from the fact that pilots cannot access real-time data about satellite movements, leaving them unprepared to recognize strange lights in the sky. These satellites may appear to move in unexpected ways, based on their orientation, and they may also appear and disappear, since their solar arrays reflect sunlight at different angles when deployed, relative to the pilot’s position in flight.

Starlink satellites orbit about 342 miles above Earth, according to Starlink’s website, and that places them lower than most other satellites, making them visible to our eyes as spots of light, no magnification needed. More than 6,000 Starlink satellites are currently circling Earth, and the SpaceX-owned company aims to eventually have 42,000 satellites in low-Earth orbit, which means pilots will need to have surefire methods for identifying them.

Four scientists want to fill the information gap in this type of situation to prevent unnecessary aviation risk. Led by mechanical engineer Douglas J. Buettner of the University of Utah, the team devised a method to simulate the exact locations of satellites, and they proposed plans that would provide pilots with the information they need to quickly identify satellites. Their paper describing this work was accepted at the 2024 International Academy of Astronautics Conference on Space Situational Awareness (ICSSA).

To shed some light on what the five pilots saw, the scientists conducted an “astrometric analysis” of their reports, using two cell phone photos and a video the pilots had taken of “an unrecognized and possibly anomalous phenomenon,” according to the paper. To corroborate the data, researchers looked up Starlink’s records, noting that the visual line the satellites created in the sky—called a “train” of satellites—launched that same day. The team also used data from the flight, including photographs taken in the cockpit. Using these pieces of information and an orbital mechanics software tool, they were able to reconstruct the August 10 cockpit view. It showed Starlink satellites matching both the time and place of the sighting.

Their analysis used a technique called “ray-traced rendering” of the view from the pilots’ cockpit, which provided a more visual simulation of exactly where the pilots saw the satellites through their cockpit windows, according to the paper. The simulation experiments indicated that the satellites’ solar arrays must have been deployed, likely making them glint brightly enough for the pilots in both aircraft to notice them. “In the implementation of our approach, we were able to closely match the apparent speed in degrees per second traveled by the object between the two photographs taken by one of the pilots,” the scientists wrote.

The team hopes that their work demonstrates a plan that could plausibly “warn aviators and the public about satellites that could be visible in unusual or novel illumination configurations,” and therefore support aviation safety, they wrote. In the future, it’s worth studying how the deployment of a satellite—as well as its surface materials—affects the way it reflects sunlight, the paper adds. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has said on X that the satellite orientation could be adjusted to minimize solar reflection during astronomical experiments, though the team’s paper does not specifically address this possibility.

The authors do suggest various procedures and technologies that aircraft could deploy to support accurate UAP identification. For example, pilots should be allowed to “routinely provide photographic evidence from either an automated system when they are busy with safety critical aircraft operations, or using cell phones when they are not allowed,” to greatly improve UAP analysis.

Satellite operators should also provide information about satellite movements—such as orientation, orbit location, and deployment timelines—to support more accurate and detailed models, the scientists write. Finally, they suggest a way for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to reduce in-flight risks due to pilots trying to determine the source of a UAP. Air traffic controllers could have access to a satellite-modeling system that would enable them to anticipate satellite sightings and alert the pilots when necessary. “We envision this as a collaborative effort between the satellite’s owners (in this case SpaceX/Starlink), the FAA, NASA, NOAA, and the U.S. Space Force,” the authors note.

As for people on the ground, anyone can find Starlink in the sky. Look up on a clear, dark night, and if you see a white light or “train” of lights moving across the sky, go to FindStarlink.com. You can search for your time and location and determine if what you see is indeed Starlink satellites.

Before joining Popular Mechanics, Manasee Wagh worked as a newspaper reporter, a science journalist, a tech writer, and a computer engineer. She’s always looking for ways to combine the three greatest joys in her life: science, travel, and food.