Is Brainwashing Possible? Here’s What History Says

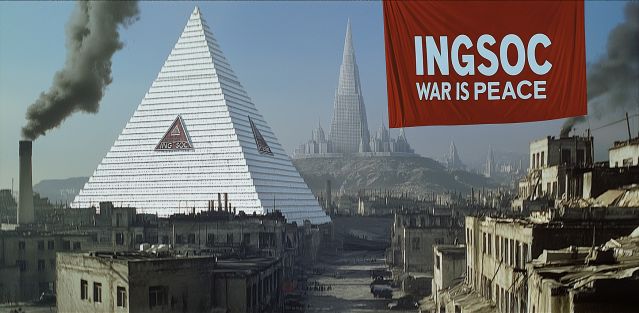

In George Orwell’s novel 1984, the entire world is controlled by three totalitarian superstates. Britain, or “Airstrip One,” is ruled by a single party, Ingsoc, with its cult of personality surrounding the dictator known simply as “Big Brother.” This government aims for total control over private thought and belief; its Ministry of Love uses torture and gaslighting to reeducate “thought criminals.”

Could this really happen? In late 2023, novelist Sandra Newman published a parallel novel, Julia, retelling 1984 from a female perspective. Newman’s vision of Orwell’s nightmare focuses on the same themes of propaganda, surveillance, and brainwashing, while offering a slightly different conclusion. And so, the feasibility of Orwell’s nightmare is up for consideration.

To explore whether “mind control” as depicted in fiction and popular culture is really possible, a brief history lesson is in order.

The Cold War and MKUltra

Orwell wrote the original novel from 1947 to 1948, during the early years of the Cold War (a term Orwell himself is credited for popularizing). During this period of ideological tension, fears over communist indoctrination stirred. Though Orwell didn’t live to see it, having died in January 1950, the ‘50s soon erupted with an all-out obsession over “brainwashing” after some American POWs became communist sympathizers during captivity in the Korean War.

Partly catalyzed by this red scare, the CIA launched a project, MKUltra, to test and develop new brainwashing tactics, which focused heavily on the psychedelic drug LSD. Subjects for MKUltra were not volunteers, but, rather, unconsenting victims. After many grossly unethical experiments, the CIA eventually concluded that LSD’s effects, while powerful, were too unpredictable to be useful for mind control.

In short, brainwashing is largely pseudoscience. The concept is no longer taken seriously by most psychologists, and it’s no longer generally admissible as a defense in U.S. criminal courts.

That’s not to say that subtler forms of psychological manipulation are impossible, or even that one cannot be stripped of one’s identity through trauma. But the stories of ideological defection in Korean War POWs don’t require much in the way of new psychological theories or techniques. In the end, any ideological belief change that occurred in POW camps is likely explainable in terms of survival mechanisms activated during extreme stress and isolation.

Call this brainwashing if you like, but it’s not the sort of brainwashing that Big Brother could use with total efficacy. If the purpose of 1984’s Ministry of Love is to reeducate doomed prisoners so they cannot remain defiant—even privately—to the day of their executions, then I predict such a project would very often fail.

This skepticism was largely shared by Aldous Huxley, author of the other great dystopian novel Brave New World. Huxley wrote to Orwell: “Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power […]”. On the other hand, contrary to the later conclusion of MKUltra, Huxley did believe that mind control was achievable using hypnosis and drugs.

Of course, most of 1984’s other horrors are fully realizable. As such, even a mere attempt toward the sort of reeducation that the Ministry of Love aspires to would be one of humanity’s most despicable projects ever, on par with Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulags. And yet, if total indoctrination were possible, then it is surprising that 20th-century totalitarianism in Germany and Russia didn’t already accomplish it.

Fiction as thought experiment

Reading Orwell’s 1984 as a young teenager catalyzed a loss of innocence. At an impressionable age, the novel’s ending suggested to me that love and hate can be flipped with sufficient force.

This isn’t entirely wrong: thoughts and feelings are indeed fleeting. The self, as we commonly understand it, is not a solid or immutable core. MKUltra was on to something with LSD, as powerful psychedelics really can weaken or temporarily dissolve the ego. But Orwell’s terrifying hypothesis, that sincere love for a dictator can be aroused by a combination of torture and gaslighting, doesn’t necessarily follow from this.

Some readers will run Orwell’s fictional scenario, or thought experiment, with different results. This is, naturally, a shortcoming of thought experiments. They are not real experiments. But the Ministry of Love is obviously not an ethical experiment to run in real life (and neither was MKUltra, for that matter). Hence, the value of both formal thought experiments (in academic philosophy) and informal thought experiments (in fiction).

Just as researchers attempt to replicate each other’s findings in science, literary authors may attempt to replicate each other’s findings in fiction. In this light, Sandra Newman’s recent novel Julia is a valuable follow up experiment that questions some of Orwell’s conclusions.