Are COVID-19 conspiracy theories for losers? Probing the interactive effect of voting choice and emotional distress on anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic has increasingly become intertwined with politics, emerging studies have identified political orientations as essential drivers behind public endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Yet little is known about the relationship between individuals’ voting choices and their conspiracy beliefs, as well as the psychological mechanism behind them. By introducing affective intelligence theory (AIT) into the conspiracy theory literature, this study examines the moderating role of emotional distress as the underlying mechanism that conditions the relationship between voting choice and the public’s anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs. A cross-national online survey of adults (aged 18 or above; n = 2208) was fielded in Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, and the US in June 2021. The results show that individuals who voted for the losing party in the previous election are more susceptible to anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, indicating a “losing effect.” Additionally, those experiencing greater emotional distress are more vulnerable to those conspiratorial statements. Moreover, the aforementioned losing effect of voting choice is weaker among individuals who experienced greater emotional distress during the pandemic. These findings enhance our understanding of the socio-psychological mechanism behind conspiracy beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The assertion that science is often utilized or distorted to advance political agendas is not novel. However, the politicisation of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the proliferation of various COVID-19 conspiracy theories, has been particularly concerning given the scale and intensity of the crisis. Recent evidence shows that belief in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories reduces vaccination willingness and uptake (Chen et al. 2022a; Đorđević et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2022; Seddig et al. 2022), thereby threatening individual health and the efficacy of public health policies. More concerning, public attitudes toward anti-vaccine conspiracy theories are found to be intertwined with political orientations, such as political ideology (Jiang et al. 2021), suggesting a pressing threat to public health from the turbulent political landscape. Therefore, understanding how political factors influence public beliefs in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories has become crucial for individual health and the health of the social system.

This study focuses on the effect of an individual’s voting choice on his or her anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs, as well as the psychological mechanism underlying this effect. Unlike prior research that has concentrated on political ideology, this study emphasises the role of voting—a crucial means for citizens to engage in politics and a key process in the distribution of power in modern society. Previous studies have suggested that individuals on the losing side of an election are more susceptible to political conspiracy theories, because conspiratorial narratives disparaging their opponents can help these “losers” cope with the increased threat of losing power and justify their own political choices (Douglas et al. 2019; Uscinski and Parent, 2014). However, little is currently known about how voting choice influences attitudes toward COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Apart from its substantial role in shaping political behaviours, emotion is also found to be a crucial antecedent for individual endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories (Kim and Kim 2021; van Mulukom et al. 2022). This study focuses on emotional distress, a prominent mental state during the pandemic (Twenge and Joiner 2020; Zhao et al. 2020). In recent decades, advances in neuroscience and political psychology—especially research on affective intelligence theory—have refuted the conventional idea that emotional experience or affective processes must follow cognitive processes (Adolphs 2008; Davidson and Irwin 1999; Mintz et al. 2021; Straube et al. 2010; Zajonc 1980). Emotional experience can occur preconsciously, and thus can serve as “the foundation of all information processing, decision-making, and behavior” (Marcus et al. 2019, p. 114). This theorization implies that emotions (including distress) may act as a conditional factor (i.e., moderator) that can alter the impact of political factors (herein one’s voting choice) on individuals’ conspiracy beliefs. Yet, existing scholarship on conspiracy theories often centres on the isolated effects of various antecedents, neglecting the potential interactive dynamics between them. By introducing affective intelligence theory (AIT) to the literature on conspiracy theories, this study fills the above research gaps by probing the following questions: How does voting choice influence individuals’ anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs? Does feeling distressed affect this voting choice effect? And if so, how?

For empirical investigation, this study incorporates data from a cross-national survey covering Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, and the US (n = 2208) conducted in June 2021. Those four jurisdictions were selected because they have similar timelines regarding exposure to the first few waves of the pandemic. Also, by the time of our survey, all four jurisdictions had launched their official vaccination programs, and were suffering from vaccine-related conspiracy theories (Lee 2021; Letters 2021; Mainichi Japan 2021; Tandoc et al. 2021). Additionally, the three East Asian jurisdictions share cultural proximity (such as Confucianism) to the epicentre of the pandemic (i.e., China) while differing in terms of their political systems. Including the US provides a Western counterpart featuring a democratic system. These similarities and differences enable us to check and compare our models and findings across contexts, and thus help generate deeper insight into the psychological mechanism that drives the public’s anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs.

Defining conspiracy theories and conspiracy beliefs

Conspiracy theories, by their very nature, are social and political. They often attempt “to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots by two or more powerful actors” (Douglas et al. 2019, p. 4). Typically, these “secret plots” promote the interests of a handful of actors, “the conspirators,” at the expense of public interest or the common good (Uscinski et al. 2016). This conceptualization of conspiracy theory distinguishes this concept from rumours and misinformation which are not characterized by malicious intent on the part of actors (De Coninck et al. 2021; Hong et al. 2021). Moreover, though not necessarily addressing the government, the actors of conspiracy theories usually refer to powerful persons or groups (Douglas et al. 2019; Goertzel 1994). Grounded on the above conceptualization, conspiracy beliefs are construed as “belief[s] in a specific conspiracy theory, or set of conspiracy theories” (Douglas et al. 2019, p. 4).

Recent evidence highlights the importance of differentiating conspiracy beliefs from conspiracy mentality, especially when examining related antecedents of conspiracy beliefs. Conspiracy mentality, also referred to as “conspiracy predispositions” (Uscinski and Parent 2014), “conspiracy thinking” (Walter and Drochon 2022) and “conspiracy mindset” (Sutton and Douglas 2020), “describes the general propensity to subscribe to theories blaming a conspiracy of ill-intending individuals or groups for important societal phenomena” (Bruder et al. 2013, p. 2). Results from a meta-analysis (Stojanov and Halberstadt 2020) have shown that, compared to beliefs in specific conspiratorial statements, conspiracy mentality is less likely to be influenced by a perceived lack of control. A recent overview (Imhoff, Bertlich, Frenken 2022) has demonstrated that conspiracy mentality is “probably a relatively pure measure of accepting the existence of conspiracies” (p. 4), highlighting its stability as a disposition and robustness as a predictor of specific conspiracy beliefs. Moreover, scholars have identified a significant linkage between political orientation and conspiracy mentality (Imhoff, Zimmer, Klein et al. 2022), suggesting a possible confounding effect of the latter on the relationship between voting choice and conspiracy beliefs. Therefore, our analysis includes conspiracy mentality as an important control variable.

Voting for opposition parties and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Social motive, specifically “the desire to belong and to maintain a positive image of the self and the in-group,” is a major driving force facilitating conspiracy beliefs (Douglas et al. 2017, p. 540). When such a social need arises, conspiracy theories implicating the competing out-groups gain appeal as they help people valorise the images of themselves and their in-groups (Douglas et al. 2017). This is particularly the case for individuals on the losing side of a political process like an election (Douglas et al. 2019; Edelson et al. 2017). Moreover, scholars have also argued that conspiracy theories can serve as an important measure to cope with perceived dangers for vulnerable groups, especially out-of-power groups after an election (Uscinski and Parent 2014). This is because losing an election means becoming disadvantaged in the distribution process of power and resources, thus making conspiracy theories which demonize the opponent attractive and resonant among the out-of-power groups (Uscinski and Parent 2014).

Prior studies have found empirical evidence supporting the above theorization. Based on a long-term content analysis of letters to the editor of the New York Times, scholars found that during the terms of Republican presidents, most conspiracy theories targeted the right and capitalists, whereas when a Democrat took office, most conspiracy theories targeted the left and communists (Uscinski and Parent 2014). Using longitudinal data collected before and after the 2012 US election, Edelson et al. (2017) determined that electoral losers are more likely than winners to believe there has been election fraud.

Extending this line of research to the context of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, we contend that the anti-vaccine conspiracy theories could also serve the need of electoral losers to validate themselves by painting the incumbent (or the ruling parties) in a negative light. Moreover, we argue that the above “validating role” of conspiracy theories could even be applied to conspiratorial claim that does not directly involve the incumbent (e.g., “the only reason the COVID-19 vaccine is being developed is to make money for pharmaceutical companies”). Specifically, considering that all of these vaccines have been approved by their respective governments and even included in official vaccination programs,Footnote 1 conspiratorial claim about the vaccines could be deemed implicit accusations against the incumbent, thereby serving to help uphold the in-group and self-image of individuals who supported the losing parties in the former election.

That said, some may suspect that the impact of losing the election could be temporary. Yet, a recent study of the 2010 Swedish general election demonstrated that the experience of losing an election is not “a temporary disappointment with the election outcome but rather a relatively long-lasting aspect of how voters regard the functioning of the democratic system” (Dahlberg and Linde 2017, p. 638). In fact, this “losing effect” has been found to last for nearly the entire electoral cycle (Dahlberg and Linde 2017). This finding suggests that the distance between the latest election and the prevalence of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories may have little impact on the relation between voting choice and conspiracy beliefs. As such, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1: People voting for opposition parties will be more likely to believe in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories.

Emotional distress and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Past experimental studies demonstrated that conspiracy beliefs are emotional-driven (e.g., van Prooijen and Jostmann 2013; Whitson et al. 2015). The “dual-process models” (Evans 2008) posit that the human mind processes information about the environment with two functional systems, with one system operating rapidly by relying on intuitions and emotions (System 1) and the other operating slow with its reliance on analytical thinking and rational deliberation (System 2). A recent overview of the social-cognitive processes of conspiracy beliefs concluded that those beliefs derive from System 1 thinking, as empirical studies have consistently identified intuitive thinking and uncertainty-related emotions as key predictors (van Prooijen et al. 2020). For instance, utilizing two experimental studies, van Prooijen and Jostmann (2013) have recognized a positive effect of experiencing anxious uncertainty on conspiracy beliefs.

Grounded on these findings, we hypothesize that experiencing emotional distress can also induce one’s beliefs in conspiracy theories, especially those about COVID-19 vaccines. Emotional distress, or “psychological distress,” is “a state of emotional suffering typically characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety” (Arvidsdotter et al. 2016). Scholars (van Prooijen and Douglas 2017, 2018) have noted that conspiracy theories flourish after the occurrence of distressing and anxiety-provoking events, “such as a fire, a disease epidemic, a war, a plane crash, or a terrorist strike” (van Prooijen and Douglas 2017, p. 326), suggesting a link between distress and conspiracy beliefs. Drawing on a series of experiments, Whitson et al. (2015) found that experiencing uncertain emotions like anxiety, a key component of distress, increases one’s belief in conspiracy theories. This is because those conspiratorial discourses can help people “regain a sense of perceived control over the uncertain landscape” by offering a simplified explanation of the current events (Whitson et al. 2015, p. 89). More pertinent to our study, recent surveys of COVID-19 conspiracy theories have documented a positive correlation between distress and conspiracy beliefs (De Coninck et al. 2021; Simione et al. 2021). The above discussion generally implies a positive association between emotional distress and endorsement of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2: People with more intense emotional distress will be more likely to believe in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories.

Emotional distress as a moderator of voting choice

Guided by affective intelligence theory, we further scrutinize the potential role of emotional distress in the relationship between voting choice and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs. Affective intelligence theory, drawing on insights from neuroscience, suggests that affective appraisal occurs preconsciously. This positions an individual’s emotional experience as the basis for all consciousness-based information processing, decision-making, and behaviours (Marcus et al. 2019). This argument suggests that emotion can serve as a condition that determines how the cognitive process functions.

More specifically, in the literature on AIT, uncertainty-related emotions such as distress, anxiety, and fear have garnered substantial scholarly attention. These emotions have been found to make individuals less reliant on their existing stances or habits when managing affairs or responding to the environment (Gervais 2019; MacKuen et al. 2007; Marcus et al. 2000, 2019). It is because these emotions often arise when individuals encounter a novel threat with an uncertain cause, leading to a sense of lack of control (Lerner and Keltner 2001). To alleviate this feeling of uncertainty, emotionally triggered individuals tend to seek out additional information, even from sources that contradict their political beliefs (Albertson and Gadarian 2015; Valentino et al. 2008). The acquisition of novel and diverse information can lead to opinion changes, particularly among anxious individuals, thereby diminishing the influence of their existing political standpoints on their responses to the surroundings (MacKuen et al. 2007; Marcus et al. 2000).

Empirical evidence has lent support to this theorization. For instance, Marcus et al. (2019), utilizing three survey studies, demonstrated that fear reduces the likelihood of voting for a far-right party (Front National), especially among centre-right and far-right party identifiers; also, they found that fear can increase acceptance of authoritarian policies (i.e., stricter security measures), particularly among left-leaning who typically oppose such measures. Similarly, a recent study using cross-national panel data revealed that higher levels of fear and governmental trust are associated with greater public support for liberty-restricting public health measures, such as curfews and mobile phone surveillance. However, the positive relationship between governmental trust and support for liberty-restricting measures weakens among individuals with greater fear over the COVID-19 pandemic (Vasilopoulos et al. 2022).

Although prior research on AIT has primarily focused on public attitudes and decision-making processes in political context, this study extends the theory to the realm of conspiracy beliefs. As discussed above, conspiracy theories are inherently political, often implicating powerful figures and groups as conspirators. Therefore, based on this line of reasoning, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: Feelings of distress will attenuate the relationship between voting choice and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs.

Methods

Data

This study relies on cross-national survey data collected in Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, and the US between June 11 and 30, 2021, a time period when the pandemic in each region turned relatively stable. Though, as noted earlier, the influence of losing an election has been shown to persist throughout the entire electoral cycle (Dahlberg and Linde 2017), our data collection spans four jurisdictions with varying intervals between their most recent elections and the time of data collection, allowing us to make comparisons based on the length of the intervals. Specifically, Singapore and Hong Kong held their general and legislative elections on 10 July 2020 and 4 September 2016, respectively. Japan conducted its general election on 22 October 2017, while the United States completed its presidential election on 3 November 2020.

The survey was administered by a global data company, Dynata. For the four regions examined, the company-owned online panels comprised 56,000 to 2,350,000 registered users, among whom our samples were obtained via opt-in online surveys. Data collection based on online panels can be conducted quickly for time-sensitive projects (Callegaro et al. 2014; Wright 2005), such as studies on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our surveys targeted adult residents (18 and over) in each jurisdiction. Quota sampling method was employed to recruit participants with characteristics that approximated the general population. The data company sent email invitations to registered panel members, inviting them to log into the survey platform to complete the questionnaire via computers or mobile phones. This recruiting procedure was continued until the pre-determined quota was met. To increase the response rate, upon completing the surveys, participants were rewarded with credits to redeem for cash or goods. The response rates of the four jurisdictions ranged from 15% to 30%. The questionnaire was prepared in English, Chinese, and Japanese. After removing cases with incomplete information, a sample of 2,208 respondents was obtained.

Regarding the demographics of the sample, less than half of the respondents were aged under 40 (44.4%), and there were slightly more male respondents (57%) than female respondents in the sample. Additionally, most respondents had obtained a tertiary degree or above (79.3%). Nearly half of the respondents perceived themselves as middle class (47.9%), while only 20.2% of the respondents perceived their status as upper middle or upper class. To save space, detailed characteristics of the sample from each jurisdiction are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Measures

Anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs were measured by two items originating from prior research (Duffy et al. 2020). Both items were measured by asking the same question (“Please evaluate how much you disagree or agree with the following statements”) on a seven-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”). The first statement (Conspiracy Theory 1) was “The real purpose of a mass vaccination program against COVID-19 is to track and control the population,” while the second (Conspiracy Theory 2) was “The only reason the COVID-19 vaccine is being developed is to make money for pharmaceutical companies.” We then aggregated these two items into an index of anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs (Pooled data: M = 3.98, S.D. = 1.73, Spearman-Brown coefficient = 0.82). Higher scores indicated stronger belief in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories.

Voting choice

Voting choice was measured by asking which party the respondents voted for in the previous general/legislative election. Voting for opposition/losing parties was coded as 1, and voting for the ruling/winning party was coded as 0. Particularly, in Singapore, voting for People’s Action Party was coded as 0 while choosing other parties was coded as 1.Footnote 2 In Hong Kong, though the political leader (i.e., Chief Executive) is not popularly elected and the party system was fragmented, the legislative election is based on universal suffrage within a political landscape characterized by a clear cleavage between the pro-establishment/pro-Beijing camp and the opposition camp (Wong et al. 2018). Therefore, scholars usually analysed people’s voting choice in terms of the political camp they choose (Tang and Lee 2018; Wong et al. 2018). Given that the pro-Beijing camp had won a majority in the 2016 Hong Kong legislative election, those voting for parties of the opposition camp were coded as 1, and those voting for pro-Beijing parties were coded as 0.Footnote 3 For Japanese respondents, since the ruling coalition of LDP (Liberal Democratic Party)–Komeito had retained supermajority in the 2017 general election (Liff and Maeda 2019; Wakatsuki et al. 2017), voting for LDP and Komeito were coded as 0, while voting for other parties were coded as 1.Footnote 4 For the US survey, voting for the Democratic Party was coded as 0, and voting for the Republican Party or other parties was coded as 1. Abstaining from voting in the previous election or “I don’t remember/No response” was treated as a missing value.

Emotional distress

Following prior research (Chen et al. 2022b; Weathers et al. 2013), emotional distress was measured by five items. Specifically, respondents were asked to rate on a seven-point scale (1 = “not at all”; 7 = “very much”) the extent to which they have been in the following five situations over the past month: “stressed about leaving home”; “having repeated and disturbing thoughts or dreams about what is happening”; “having difficulty concentrating”; “having trouble falling or staying asleep”; “feeling irritable or having anger outburst.” Then, these five indicators were aggregated into an index of emotional distress (Pooled data: M = 3.87, S.D. = 1.77, Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

Control variables

To achieve more accurate estimations of the focal relationships, a set of variables were included in our analysis as potential confounders. As elaborated in the second section, conspiracy mentality was controlled for and measured by five questions adapted from Bruder et al. (2013). Also, to minimize the possible confounding effect of partisanship, we included trust in government as a proxy measure due to the lack of direct measurement in our dataset. Past studies showed that trust in government was significantly linked to partisanship during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kerr et al. 2021; Nielsen and Lindvall 2021; Pickup et al. 2020; Robinson et al. 2021). Additionally, authoritarianism, news use of media, perceived threat, and feeling of hope were also controlled according to prior literature (Jolley et al. 2018; Min 2021; Peitz et al. 2021; Richey 2017; Wood and Gray 2019). We also included gender, age (1 = “18-29”; 2 = “30-39”; 3 = “40-49”; 4 = “50-59”; 5 = “60 or above”), education level (1 = “secondary or below”; 2 = “tertiary or above”), and social class (1 = “lower or lower middle class”; 2 = “middle class”; 3 = “upper middle or upper class”) as control variables. Country dummy variables were included when we conducted model fitting with the pooled data. Singapore was assigned as the reference group. Descriptives and complete measures of all control variables were provided in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Note.

Results

Before model testing, multicollinearity diagnostics were checked for the pooled and regional data. Variance inflation factors (VIF) ranged from 1.03 to 3.46, which was acceptable according to O’brien (2007) who suggested VIF should be less than 5. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were applied to the model fitting.

Hypothesis 1 posited a positive relationship between voting for opposition parties in the former election and belief in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. As shown in Table 1, all other conditions being equal, compared to respondents voting for the incumbent party, people who voted for the opposition parties were more likely to believe the anti-vaccine conspiracy theories (β = 0.077, p < 0.001, in Model 1 Table 1). This result was consistent across the three jurisdictions (Hong Kong: β = 0.141, p < 0.001, in Model 13 Table 3; Japan: β = 0.1, p = 0.008, in Model 19 Table 4; the US: β = 0.058, p = 0.027, in Model 25 Table 5) but not in Singapore (β = 0.006, p = 0.86, in Model 7 Table 2). Furthermore, analyses using each conspiracy theory as the dependent variable also generated similar results patterns, except for Singapore and Japan (in Japan, voting choice was only positively related to beliefs in Conspiracy Theory 1). Hence, Hypothesis 1 was at least partly supported.

Hypothesis 2 presumed a positive relationship between one’s emotional distress and belief in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. The findings presented in Model 1 in Table 1 demonstrated that distress had a significant positive association with the anti-vaccine conspiracy belief index (β = 0.312, p < 0.001). Moreover, this relationship was consistent across the four regions (Singapore: β = 0.28, p < 0.001, in Model 7 Table 2; Hong Kong: β = 0.439, p < 0.001, in Model 13 Table 3; Japan: β = 0.166, p < 0.001, in Model 19 Table 4; the US: β = 0.341, p < 0.001, in Model 25 Table 5). Analyses using each conspiratorial statement as the dependent variable also showed the same result. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

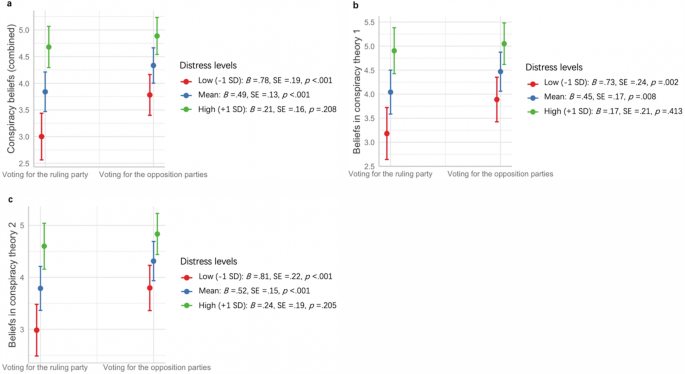

Hypothesis 3 presumed a negative moderating effect of emotional distress on the association proposed in H1. Results from Model 2 in Table 1 showed that the positive relationship between voting for the opposition parties and conspiracy beliefs was attenuated by emotional distress (β = −0.075, p < 0.001, also see Fig. 1), which supported H3. Specifically, as illustrated in Fig. 2, individuals voting for opposition parties exhibited significantly stronger beliefs in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories compared to those voting for the ruling parties when experiencing moderate or low levels of emotional distress (moderate level: B = 0.28, S.E. = 0.06, p < 0.001; low level: B = 0.48, S.E. = 0.08, p < 0.001). However, when individuals experienced extreme emotional distress, their voting choice in the previous election no longer differentiated their beliefs; under such conditions, they consistently expressed strong beliefs in these conspiracy theories regardless of their voting behaviour (B = 0.09, S.E. = 0.08, p = 0.254).

Furthermore, regional analyses showed that such a negative moderating effect of distress was statistically significant in both Hong Kong (β = −0.149, p = 0.014, in Model 14 Table 3) and the US (β = −0.111, p < 0.001, in Model 26 Table 5), but not in Singapore (β = −0.028, p = 0.513, in Model 8 Table 2) or Japan (β = 0.02, p = 0.668, in Model 20 Table 4). Additionally, in both Hong Kong and the US, individuals voting for the opposition parties expressed significantly stronger conspiracy beliefs compared to those voting for ruling parties, particularly when they experienced low to moderate levels of distress. However, this difference diminished when individuals experienced high levels of distress, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. Moreover, when using each conspiracy theory as the dependent variable, this interactive relationship between voting choice and emotional distress still held in Hong Kong, the US, and the pooled data. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was partly supported.

Discussion

Relying on cross-national survey data, we have scrutinized the role of voting choice and emotional distress, and their interactive dynamics in shaping individual beliefs about anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. In summary, all our hypotheses have been at least partly supported: people voting for the opposition parties in the former election (Hypothesis 1) and those experiencing greater emotional distress (Hypothesis 2) are more tilted toward conspiratorial statements against the COVID-19 vaccines; this positive relationship between voting choice and conspiracy beliefs turns weaker when people experience more emotional distress (Hypothesis 3).

Our finding on voting choice and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs resonates with the conventional wisdom that “conspiracy theories are for losers” (Uscinski and Parent 2014, p. 130). For people voting for the losing parties in an election, conspiracy theories implicating the incumbent are particularly attractive because they can justify individuals’ political choices and uphold a positive image of themselves and their in-groups. This finding remains robust even after controlling for conspiracy mentality, which rules out the possibility that individuals are equally likely to believe any conspiracy theory about an out-group. Additionally, we include governmental trust as a proxy measure for partisanship, a potential confounder that could influence the relationship between voting choice and conspiracy beliefs. Moreover, as expected, this finding even extends to anti-vaccine conspiracy theories that do not directly involve the incumbent. Specifically, the explicit actor in Conspiracy Theory 2 is pharmaceutical company. Yet, our analysis shows that the effect size of voting choice in the case of Conspiracy Theory 2 is comparable to that in the case of Conspiracy Theory 1. This result suggests that conspiracy beliefs driven by political bias tend to be pervasive, as long as the conspiratorial claims help justify individuals’ political choices, either directly or indirectly. Due to this political bias, official efforts to debunk vaccine-related conspiracy theories may be ineffective, especially among citizens supporting the losing parties in the most recent election. Thus, the roles of other actors (i.e., other than the current administration, such as the media, opposition parties, and NGOs) in fighting conspiratorial information on vaccines should be further valued, by both policy-makers and practitioners.

Our findings also revealed additional nuances based on regional variation. In both Hong Kong and the US, the relationship between voting choice and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs is particularly salient and consistent across the two conspiratorial claims (compared to that in Japan and Singapore). This pattern is probably due to the growing political polarisation in Hong Kong and the US in recent years (Chan and Fu 2017; Ding and Lin 2021; Jahani et al. 2022; Lee 2016). As politics become more contentious and polarised, issues surrounding COVID-19 vaccines, including related conspiratorial narratives, may be increasingly weaponised as tools for political contestation, thereby amplifying the role of voting choice in shaping conspiracy beliefs.

In Japan, voting for the losing party was found to correlate with beliefs in Conspiracy Theory 1 but not Conspiracy Theory 2, the latter of which does not explicitly implicate the incumbent. This suggests that the connection between voting choice and conspiracy beliefs may depend on the extent to which the conspiratorial claim targets the ruling party. Notably, the varied intervals between the most recent elections and our data collection (Hong Kong: 57 months; Japan: 44 months; US: 8 months) suggest that the “losing effect” tends to persist over time, aligning with prior research (Dahlberg and Linde 2017). However, this effect is absent in Singapore, which is somewhat expected given its lack of competitive elections and ruling party alternation. The absence of a counterfactual condition in elections may diminish the predictive power of voting choice for conspiracy beliefs in this context. Taken together, our regional findings indicate that while the persistence of the losing effect is not sensitive to the time elapsed since an election, its strength is influenced by the level of political competitiveness within the region.

Our investigation of emotional distress reaffirms the emotional roots of conspiracy beliefs (van Prooijen et al. 2020). Consistent with recent evidence (Simione et al. 2021), our finding shows that individuals experiencing higher levels of distress are more vulnerable to COVID-19 conspiracy theories. This finding indicates that when encountering a novel threat like the COVID-19 pandemic, uncertainty-related emotion like distress would drive individuals’ judgment on pandemic-related conspiracy theories, since the latter could mitigate one’s feeling of uncertainty and loss of control by providing a simplified explanation of the situation at hand (Whitson et al. 2015). This finding implies that emotional distress may endanger individual health and paralyse public health initiatives as it can raise anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs that are found to impair vaccination intentions (Chen et al. 2022a; Đorđević et al. 2021). More concerning is that the effect of distress is quite robust across the four jurisdictions examined, with the magnitude of the effect even comparable to that of conspiracy mentality. The effect of emotional distress is also consistently stronger than that of voting choice, authoritarianism, media use, and socioeconomic factors. This indicates that individuals’ anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs are primarily emotion-driven.

Furthermore, by extending affective intelligence theory to the context of conspiracy theories, we have identified a moderating effect of emotional distress that mitigates the association between voting choice and anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs. This finding corresponds with the AIT theorization that when facing a novel external threat like COVID-19, experiencing uncertain emotions like distress reduces individuals’ reliance on their current political stance, in their attitude formation and decision-making processes (Vasilopoulos et al. 2018). Nonetheless, distress itself could be harmful to personal health and the execution of public health policies, regardless of its role in restraining the politicisation of vaccine-related conspiracy theories. This finding also implies that as people are normalized to the pandemic and their emotional distress start to wane, the weight of political stance in shaping conspiracy beliefs will increase. This means that, to more effectively counter conspiracy beliefs, stakeholders should consider reallocating resources among various actors (both official and unofficial) responsible for addressing vaccine-related conspiracy theories, based on the different stages of the pandemic.

This study expands our understanding of the socio-psychological mechanism underpinning conspiracy beliefs. As one of the pioneering studies examining the role of voting choice in the context of conspiracy theories, it reveals that past political behaviours, such as voting, can influence individual’s attitudes toward conspiratorial statements about health issues like COVID-19 vaccines. Furthermore, by introducing AIT into conspiracy theory research, this study elucidates the fundamental role of emotion in shaping individual conspiracy beliefs: uncertainty-related emotions such as distress not only directly influence conspiracy beliefs but also modify the impact of political factors like voting choice.

This study is admittedly limited in several respects. First, by utilizing cross-sectional data, we could not discern the causality behind the relationships examined, especially for the effects of emotional distress. Therefore, future research is needed to retest those relationships with longitudinal data. Second, we have examined the moderating role of only one negative emotion (i.e., distress) through the lens of AIT, leaving other emotions, such as anger, unexamined. Future research is needed to compare the roles of different types of emotions in shaping conspiracy beliefs. Third, it is sensitive to ask about respondents’ voting choices, especially in non-democratic societies like Singapore and Hong Kong, since people may face more political risk when overtly expressing support for opposition parties. To address this issue, we first checked the vote percentages for both the ruling party and the opposition parties in our data, which generally reflected the actual voting results in each jurisdiction. Also, for each region, we performed a correlation analysis using authoritarianism and voting for opposition parties which was pertaining to one’s political ideology. The results show that the correlation coefficient in Singapore (r = −0.111, p < 0.01) is comparable to those in Japan (r = −0.125, p < 0.001) and the US (r = −0.085, p < 0.01), suggesting there is no systematic bias in our measurement of voting choice. Yet, surprisingly, the negative correlation was particularly pronounced in Hong Kong (r = −0.336, p < 0.001). This is probably due to the series of pro-democracy social movements and protests triggered by the “Anti-Extradition Bill Movement” in 2019, which has garnered extensive support across demographics (Fong 2022). Conceivably, after those movements, people still voting for the incumbent (or the so-called “pro-establishment camp”) would be more likely to tilt toward authoritarianism. Fourth, while we use a single-item measure of governmental trust as a proxy for partisanship, its validity may differ between bi-party (e.g., the US and Hong Kong) and multi-party (e.g., Japan) systems. Future study should include direct and contextualized measures of partisanship to improve the estimation. Lastly, using dummy variables to control the regional influence, we were unable to examine the potential mechanisms underlying the regional difference. For instance, as discussed above, the divergent effects of voting choice on conspiracy beliefs detected in the four jurisdictions may depend on the extent of political polarisation in each society. However, empirical examination of this assumption would require a larger dataset covering more societies. Therefore, we encourage future study to explore the possible influence of contextual-level factors, and to re-examine our model by checking for potential interactions between contextual-level and individual-level factors in shaping conspiracy beliefs.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

-

For detailed information on official permission for the vaccines used in vaccination programs in the four jurisdictions, see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022), Government of Singapore (2022), Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2022), and the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2022).

-

For Singaporean respondents, voting for Workers’ Party, Singapore People’s Party, Singapore Democratic Party, National Solidarity Party, Singapore Democratic Alliance, Reform Party, Singaporeans First, People’s Power Party, or other opposition parties were coded as 1.

-

For Hong Kong respondents, voting for Civic Party, CP–PPI–HKRO, the Democratic Party, Demosisto, Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood, Labour Party, League of Social Democrats, People Power, or other opposition parties were coded as 1; voting for Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong, Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions, Liberal Party, New People’s Party, or other pro-establishment/pro-Beijing parties were coded as 0

-

For Japanese respondents, voting for Constitutional Democratic Party, Democratic Party for the People, Japanese Communist Party, Japan Innovation Party, Social Democratic Party, Reiwa Shinsengumi, NHK Party, or other opposition parties were coded as 1

References

-

Adolphs R (2008) Fear, faces, and the human amygdala. Curr Opin Neurobiol 18(2):166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.006

-

Albertson B, Gadarian S (2015) Anxious politics: Democratic citizenship in a threatening world. Cambridge University Press

-

Arvidsdotter T, Marklund B, Kylén S et al. (2016) Understanding persons with psychological distress in primary health care. Scand J Caring Sci 30(4):687–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12289

-

Bruder M, Haffke P, Neave N et al. (2013) Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Front Psychol 4:225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225

-

Callegaro M, Baker R, Bethlehem J et al. (2014) Online panel research: History, concepts, applications, and a look at the future. In: Callegaro M, Baker R, Bethlehem J et al. (eds) Online panel research: A data quality perspective. Wiley, West Sussex, p 1-12

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) COVID-19 vaccination program operational guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/covid19-vaccination-guidance.html

-

Chan C, Fu K (2017) The relationship between cyberbalkanization and opinion polarization: Time-series analysis on Facebook pages and opinion polls during the Hong Kong Occupy Movement and the associated debate on political reform. J Comput-Mediat Comm 22(5):266–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12192

-

Chen X, Lee W, Lin F (2022a) Infodemic, institutional trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A cross-national survey. Int J Env Res Pub He 19(13):8033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138033

-

Chen X, Lin F, Cheng EW (2022b) Stratified impacts of the infodemic during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey in 6 Asian jurisdictions. J Med Internet Res 24(3):e31088. https://doi.org/10.2196/31088

-

Dahlberg S, Linde J (2017) The dynamics of the winner–loser gap in satisfaction with democracy: Evidence from a Swedish citizen panel. Int Polit Sci Rev 38(5):625–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512116649279

-

Davidson RJ, Irwin W (1999) The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends Cogn Sci 3(1):11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01265-0

-

De Coninck D, Frissen T, Matthijs K et al. (2021) Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: Comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front Psychol 12:646394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394

-

Ding C, Lin F (2021) Information authoritarianism vs. information anarchy: A comparison of information ecosystems in Mainland China and Hong Kong during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. China Rev 21(1):91–106

-

Đorđević JM, Mari S, Vdović M et al. (2021) Links between conspiracy beliefs, vaccine knowledge, and trust: Anti-vaccine behavior of Serbian adults. Soc Sci Med 277:113930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113930

-

Douglas K, Sutton RM, Cichocka A (2017) The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 26(6):538–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

-

Douglas KM, Uscinski JE, Sutton RM et al. (2019) Understanding conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol 40:3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

-

Duffy B, Beaver K, Meyer C (2020) Coronavirus: Vaccine misinformation and the role of social media. The Policy Institute. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/coronavirus-vaccine-misinformation.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Edelson J, Alduncin A, Krewson C et al. (2017) The effect of conspiratorial thinking and motivated reasoning on belief in election fraud. Polit Res Quart 70(4):933–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917721061

-

Evans JS (2008) Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 59:255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

-

Fong BC (2022) Movement-voting nexus in hybrid regimes: Voter mobilization in Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill Movement. Democratization 29(7):1186–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2022.2037566

-

Gervais BT (2019) Rousing the partisan combatant: Elite incivility, anger, and antideliberative attitudes. Polit Psychol 40(3):637–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12532

-

Goertzel T (1994) Belief in conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol 15(4):731–742. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791630

-

Government of Singapore (2022) COVID-19 vaccination. https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/vaccination. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Hong YY, Chan HW, Douglas KM (2021) Conspiracy theories about infectious diseases: An introduction. J Pac Rim Psychol 15:18344909211057657. https://doi.org/10.1177/18344909211057657

-

Imhoff R, Bertlich T, Frenken M (2022) Tearing apart the “evil” twins: A general conspiracy mentality is not the same as specific conspiracy beliefs. Curr Opin Psychol 46:101349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101349

-

Imhoff R, Zimmer F, Klein O et al. (2022) Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat Hum Behav 6(3):392–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

-

Jahani E, Gallagher N, Merhout F et al. (2022) An online experiment during the 2020 US–Iran crisis shows that exposure to common enemies can increase political polarization. Sci Rep. -UK 12(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23673-0

-

Jiang X, Su MH, Hwang J et al. (2021) Polarization over vaccination: Ideological differences in twitter expression about COVID-19 vaccine favorability and specific hesitancy concerns. Soc Media Soc 7(3):205630512110484. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211048413

-

Jolley D, Douglas KM, Sutton RM (2018) Blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel: The system-justifying function of conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol 39(2):465–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12404

-

Kerr J, Panagopoulos C, Van Der Linden S (2021) Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Pers Individ Differ 179:110892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110892

-

Kim S, Kim S (2021) Searching for general model of conspiracy theories and its implication for public health policy: Analysis of the impacts of political, psychological, structural factors on conspiracy beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Env Res Pub He 18(1):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010266

-

Lee FLF (2016) Impact of social media on opinion polarization in varying times. Commun Public 1(1):56–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047315617763

-

Lee JD (2021) The utter familiarity of even the strangest vaccine conspiracy theories. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/01/familiarity-strangest-vaccine-conspiracy-theories/617572/. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Lerner JS, Keltner D (2001) Fear, anger, and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol 81(1):146–159. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146

-

Letters (2021) Coronavirus vaccine: Hong Kong needs better messaging. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/comment/letters/article/3127453/coronavirus-vaccine-hong-kong-needs-better-messaging. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Liff AP, Maeda K (2019) Electoral incentives, policy compromise, and coalition durability: Japan’s LDP–Komeito Government in a mixed electoral system. Jpn J Polit Sci 20(1):53–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109918000415

-

Lin F, Chen X, Cheng EW (2022) Contextualized impacts of an infodemic on vaccine hesitancy: The moderating role of socioeconomic and cultural factors. Inf Process Manag 59(5):103013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103013

-

MacKuen M, Marcus GE, Neuman RW et al. (2007) The third way: The theory of affective intelligence and American democracy. In: Marcus GE, Neuman RW, MacKuen M et al. (eds) The affect effect: Dynamics of emotion in political thinking and behaviour. Chicago Scholarship Online, p 124–151

-

Mainichi Japan (2021) ’It’s a conspiracy’: What goes on in the minds of anti-mask, anti-vaccine groups? (Pt 1). The Mainichi. https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20210522/p2a/00m/0na/008000c. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Marcus GE, Neuman WR, MacKuen M (2000) Affective intelligence and political judgment. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Marcus GE, Valentino NA, Vasilopoulos P et al. (2019) Applying the theory of affective intelligence to support for authoritarian policies and parties. Polit Psychol 40(S1):109–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12571

-

Min SJ (2021) Who believes in conspiracy theories? Network diversity, political discussion, and conservative conspiracy theories on social media. Am Polit Res 49(5):415–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X211013526

-

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2022) COVID-19 Vaccines. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/vaccine.html. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Mintz A, Valentino NA, Wayne C (2021) Beyond Rationality: Behavioral Political Science in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press

-

Nielsen JH, Lindvall J (2021) Trust in government in Sweden and Denmark during the COVID-19 epidemic. West Eur Polit 44(5-6):1180–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1909964

-

O’brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41(5):673–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6

-

Peitz L, Lalot F, Douglas K et al. (2021) COVID-19 conspiracy theories and compliance with governmental restrictions: The mediating roles of anger, anxiety, and hope. J Pac Rim Psychol 15:18344909211046646. https://doi.org/10.1177/18344909211046646

-

Pickup M, Stecula D, Van Der Linden C (2020) Novel coronavirus, old partisanship: COVID-19 attitudes and behaviours in the United States and Canada. Can J Political Sci 53(2):357–364. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000463

-

Richey S (2017) A birther and a truther: The influence of the authoritarian personality on conspiracy beliefs. Politics Policy 45(3):465–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12206

-

Robinson SE, Ripberger JT, Gupta K et al. (2021) The relevance and operations of political trust in the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Adm Rev 81(6):1110–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13333

-

Seddig D, Maskileyson D, Davidov E et al. (2022) Correlates of COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Attitudes, institutional trust, fear, conspiracy beliefs, and vaccine skepticism. Soc Sci Med 302:114981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114981

-

Simione L, Vagni M, Gnagnarella C et al. (2021) Mistrust and beliefs in conspiracy theories differently mediate the effects of psychological factors on propensity for COVID-19 vaccine. Front Psychol 12:683684–683684. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.683684

-

Stojanov A, Halberstadt J (2020) Does lack of control lead to conspiracy beliefs? A meta‐analysis. Eur J Soc Psychol 50(5):955–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2690

-

Straube T, Preissler S, Lipka J et al. (2010) Neural representation of anxiety and personality during exposure to anxiety-provoking and neutral scenes from scary movies. Hum Brain Mapp 31(1):36–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20843

-

Sutton RM, Douglas KM (2020) Conspiracy theories and the conspiracy mindset: Implications for political ideology. Curr Opin Behav Sci 34:118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.02.015

-

Tandoc EC, Kim HK, Goh ZH (2021) Commentary: Misinformation threatens Singapore’s COVID-19 vaccination programme. CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/covid-19-coronavirus-conspiracy-misinformation-fake-news-400276. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Tang G, Lee FL (2018) Social media campaigns, electoral momentum, and vote shares: evidence from the 2016 Hong Kong Legislative Council election. Asian J Commun 28(6):579–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1476564

-

The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2022) About the vaccines. https://www.covidvaccine.gov.hk/en/vaccine. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

-

Twenge JM, Joiner TE (2020) Mental distress among US adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol 76(12):2170–2182. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23064

-

Uscinski JE, Klofstad C, Atkinson MD (2016) What drives conspiratorial beliefs? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Polit Res Quart 69(1):57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915621621

-

Uscinski JE, Parent JM (2014) American conspiracy theories. Oxford University Press, New York

-

Valentino NA, Hutchings VL, Banks AJ (2008) Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the internet. Polit Psychol 29(2):247–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00625.x

-

van Mulukom V, Pummerer LJ, Alper S et al. (2022) Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med 301:114912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912

-

van Prooijen JW, Douglas KM (2017) Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Mem Stud 10(3):323–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017701615

-

van Prooijen JW, Douglas KM (2018) Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain. Eur J Soc Psychol 48(7):897–908. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2530

-

van Prooijen JW, Jostmann NB (2013) Belief in conspiracy theories: The influence of uncertainty and perceived morality. Eur J Soc Psychol 43(1):109–115

-

van Prooijen JW, Klein O, Đorđević JM (2020) Social-cognitive processes underlying beliefs in conspiracy theories. In: Butter M, Knight P (eds) Routledge handbook of conspiracy theories. Routledge, p 168–180

-

Vasilopoulos P, Marcus GE, Foucault M (2018) Emotional responses to the Charlie Hebdo attacks: Addressing the authoritarianism puzzle. Polit Psychol 39:557–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12513

-

Vasilopoulos P, McAvay H, Brouard S et al. (2022) Emotions, governmental trust and support for the restriction of civil liberties during the covid‐19 pandemic. Eur J Polit Res 62(2):422–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12513

-

Wakatsuki Y, Griffiths J, Berlinger J (2017) Japan’s Shinzo Abe hails landslide victory in snap election. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2017/10/22/asia/japan-election-results/index.html. Accessed 10 Dec 2024

-

Walter AS, Drochon H (2022) Conspiracy thinking in Europe and America: A comparative study. Polit Stud -Longdon 70(2):483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720972616

-

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM et al (2013) The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). The National Center for PTSD

-

Whitson JA, Galinsky AD, Kay A (2015) The emotional roots of conspiratorial perceptions, system justification, and belief in the paranormal. J Exp Soc Psychol 56:89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.09.002

-

Wong SHW, Ma N, Lam W (2018) Immigrants as voters in electoral autocracies: The case of mainland Chinese immigrants in Hong Kong. J East Asian Stud 18(1):67–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2017.29

-

Wood MJ, Gray D (2019) Right-wing authoritarianism as a predictor of pro-establishment versus anti-establishment conspiracy theories. Pers Indiv Differ 138:163–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.036

-

Wright KB (2005) Researching Internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J Comput-Mediat Comm 10(3):JCMC1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x

-

Zajonc RB (1980) Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am Psychol 35(2):151–175. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.35.2.151

-

Zhao SZ, Wong JYH, Luk TT et al. (2020) Mental health crisis under COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, China. Int J Infect Dis 100:431–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.030

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Research Project of City University of Hong Kong [grant number 7005823]; and the Knowledge Transfer Earmarked Fund from Hong Kong University Grants Committee [grant number 6354048]. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Xiang MENG, Fen LIN; Methodology: Xiang MENG, Fen LIN, Pei ZHI; Formal analysis and investigation: Xiang MENG; Writing—original draft preparation: Xiang MENG; Writing—review and editing: Xiang MENG, Fen LIN, Pei ZHI; Funding acquisition: Fen LIN.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approvalEthical approval was obtained from the Human Subject Ethics Committee of the City University of Hong Kong (Ref No: 8-2020-04-E295-18). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Before initiating the data collection process via online survey, the authors obtained written informed consent from all participants. The informed consent section was shown at the top of the first survey page. Participants were told the length of the time of the survey, the purpose of the study, and the contact information of the project coordinators. They were also explicitly informed that their participation was voluntary and that their responses would be treated with complete confidentiality and anonymity. In addition, this study intentionally avoided collecting any identifying information, such as names, addresses, or affiliations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, F., Meng, X. & Zhi, P. Are COVID-19 conspiracy theories for losers? Probing the interactive effect of voting choice and emotional distress on anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 470 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04774-3

-

Received: 17 June 2024

-

Accepted: 17 March 2025

-

Published: 02 April 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04774-3