Sons of the Covenant: The Untold History of B’nai B’rith, the ADL, & the Assault on Dissent (Part I)

Originally posted at Dispatches from Reality, by Scipio Eruditus. dfreality.substack.com

Fraternity. Power. Silence…

“All truly dogmatic religions have issued from the Kabalah and return to it: everything scientific and grand in the religious dreams of all the illuminati, Jacob Bœhme, Swedenborg, Saint-Martin, and others, is borrowed from the Kabalah; all the Masonic associations owe to it their Secrets and their Symbols.”

— Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma, Pg. 744

Related Entries

The modern assault on political dissent and open debate — especially visible in the coordinated suppression of criticism over the conduct of Israel and the renewed Gazan genocide — did not arise in a vacuum.

It is the culmination of forces long in motion, pioneered by organizations like B’nai B’rith and its later offshoot, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). Presented to the public as defenders of tolerance and human rights, these organizations in fact developed early models of reputational warfare, economic coercion, and legal intimidation to control public discourse and shield ethnic communal interests. This series, Sons of the Covenant, traces that history from its roots in 18th-century Masonry through the creation of the ADL and into the present day — a necessary investigation into how the structures of modern Zionist censorship were built, refined, and weaponized against American society.

As an explicitly Masonic offshoot, our foray into the historical exploration of B’nai B’rith must necessarily begin with the Masonic lodges themselves. The relationship between Jewry and Freemasonry in Europe constitutes one of the most consequential but underappreciated dynamics in modern history. The Craft, styling itself as a universal brotherhood beyond confessional boundaries, played a critical role in opening civil society to Jews during the 18th & 19th century. Jacob Katz, writing on the historical interplay between the two groups, downplays the magnitude of this intersection (emphasis mine):

As far as the history of the relations between Jews and the Freemasons Is concerned, there can be no doubt where the topic belongs. Here we have an unobserved sideshow of the process of Jews becoming absorbed in European society.

— Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723–1939, Pg. 3

Far from a sideshow, Freemasonry offered Jews a unique portal into European civic life: a social institution whose very constitution “laid down that in the lodges no man could be discriminated against on the grounds of his religion” (Katz, Pg. 9).

Unlike guilds or political offices at the time, Masonic lodges professed to judge men on moral character alone. The 1723 Constitution of the London Grand Lodge famously declared (emphasis mine):

A Mason is oblig’d by his Tenure, to obey the moral Law; and if he rightly understands the Art, he will never be a stupid Atheist nor an irreligious Libertine. But though in ancient Times Masons were charg’d in every Country to be of the Religion of that Country or Nation, whatever it was, yet ’tis now thought more expedient only to oblige them to that Religion in which all Men agree, leaving their particular Opinions to themselves; that is, to be good Men and true, or Men of Honour and Honesty, by whatever Denominations or Persuasions they may be distinguish’d; whereby Masonry becomes the Center of Union, and the Means of conciliating true Friendship among Persons that must have remain’d at a perpetual Distance.

This Masonic brand of Deistic universalism thus opened a space for Jewish inclusion in the Lodge. In England and Holland, this principle saw swift realization, as well as in the early lodges of colonial America. Chronicling this early chapter of American Masonry, Samuel Oppenheim observes:

Many of the most eminent of [Mordecai Noah’s] Jewish brethren were in his day filling high and honorable places in the fraternity. The Grand Lodges of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and Louisiana… at different times elevated distinguished brethren of the Jewish faith to the dignity of Grand Mastership.

— The Jews and Masonry in the United States Before 1810, Pg. 1

Indeed, Oppenheim documents figures like Moses Michael Hays, Grand Master in Massachusetts, and Moses Seixas, Grand Master in Rhode Island, who attained the highest leadership positions in American Masonry before 1810.

In revolutionary France, Freemasonry similarly provided a hospitable climate. Katz notes (emphasis mine):

In France, by contrast, Freemasons formed a united front in favor of absolute universality. There, clearly, the Masons stood together on the side of the Jews.

— Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723–1939, Pg. 10

While somewhat outside of the scope of this series, I have discussed Napoleon’s complicated history with the Jews in Revolutionary France in my first book, Anatomy of a Revolution. By contrast, German Freemasonry exhibited a more conflicted stance. While a minority of lodges advocated for Jewish inclusion, others imposed rigid barriers, insisting that membership required adherence to Christianity (a gross irony in itself). Yet even in Germany, the Craft adapted. Lodges under French or Dutch auspices often admitted Jews, and Jewish Masons sometimes founded their own affiliated lodges. The pattern, Katz notes, was one of “persistent knocking” at the doors.

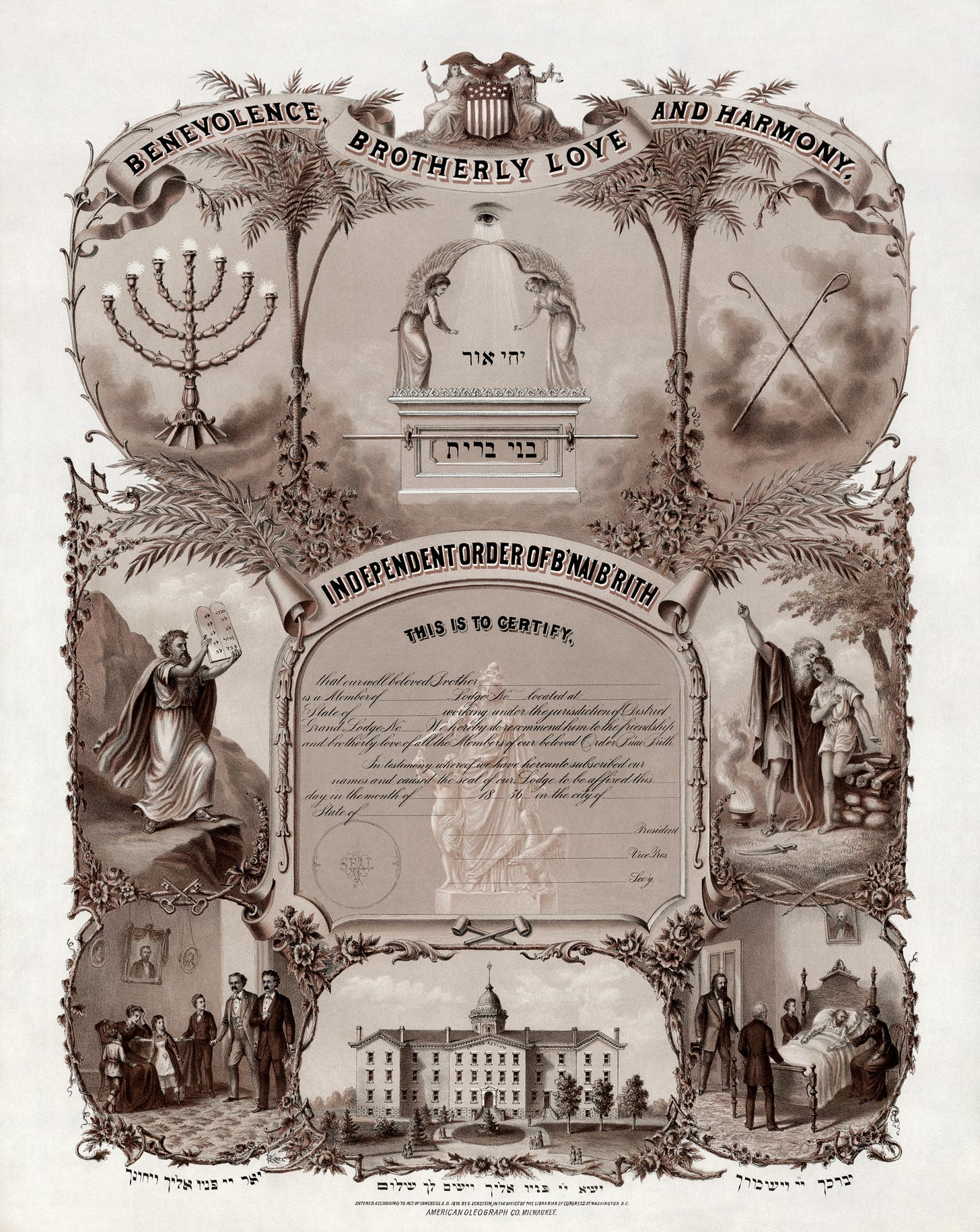

The historical integration of Jews into European civil society via Freemasonry laid critical groundwork for the founding and mission of B’nai B’rith. Far from representing a mere reaction to Masonic exclusion, B’nai B’rith (Hebrew for Sons of the Covenant) strategically embraced and adapted Masonic models of fraternity, ritual, and secrecy to forge a distinctly Jewish organization. By utilizing these powerful social frameworks, B’nai B’rith sought to establish a vehicle for internal cohesion, communal advancement, and political influence within the broader American civic landscape. As such, B’nai B’rith was not merely reflective of Masonic traditions; it was purposely crafted to become the influential force in American Jewish life and politics it has.

In this light, the later establishment of B’nai B’rith in the United States must be understood not as a reaction to exclusion but as the deliberate transplantation and modification of Freemasonry for distinctly Jewish ends. In her history of the order, Cornelia Wilhelm points out:

A large proportion of the founders is believed to have been active in Freemason or Odd Fellows lodges and greatly appreciated this form of sociability as an expression of bourgeois and religious acculturation.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, Pg. 24

The claim that B’nai B’rith emerged solely because Jews were being excluded from Masonic lodges does not withstand scrutiny.

“Masonry is a Jewish institution whose history, degrees, charges, passwords, and explanations are Jewish from the beginning to the end…”

― Dr. Isaac M. Wise, The Israelite, August 3rd, 1855

The founding of B’nai B’rith in 1843 in New York City was the natural flowering of trends long at work: Jewish participation in Masonic fraternalism and its consequent religious ideals of universalism.

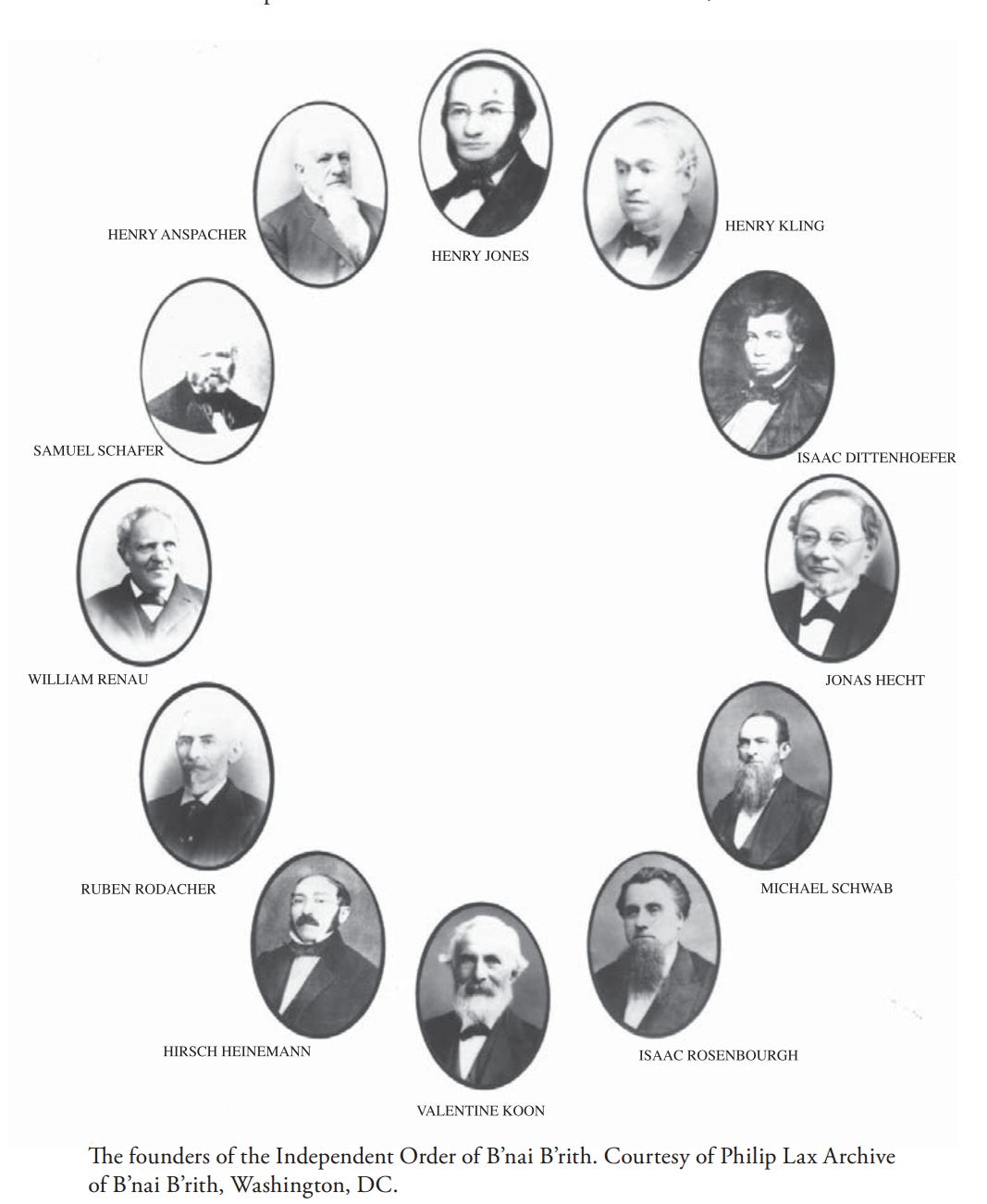

The Independent Order of B’nai B’rith was launched on Friday, October 13th, 1843, when twelve German Jewish immigrants — mainly from Hamburg and other German-speaking regions — met at Sinsheimer’s Café on Essex Street in Manhattan. The Order was thoroughly shaped by the ideology of Reform (or Progressive) Judaism, an ideology which dominated such circles. Reform, as articulated by its early leader David Einhorn, redefined Talmudic Judaism in universalistic terms. In 1857, Einhorn summarized Judaism’s essence as “older than the Israelites,” identifying it with “pure humanity” and envisioning its culmination in a “messianically perfected humanity.” Rabbinic Judaism, he argued, was not a distinct religion so much as a “priest people” called to bring divine truth to universal dominion. (Wilhelm, Pg. 53). Reform Judaism thus imagined the eventual dissolution of religious distinctions altogether into a one-world “religion of humanity.”

Cornelia Wilhelm describes the Order’s inception:

In the fall of 1843, Henry Jones and William Renau designed a ritual and drafted a constitution for the planned organization, whose founding was prepared in detail at five preliminary assemblies on October 14, October 21 (in Sinsheimer’s saloon), October 26, October 29, and November 2, 1843.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, Pg. 27

On November 5th, 1843, (an equally conspicuous date) the first formal lodge meeting was held. They adopted a constitution, elected officers, and initiated their first candidates. The early records show a careful replication of Masonic methods: degrees of initiation, secrecy, oaths, symbols, rituals — unmistakably modeled on the framework its founders had known in Germany and America. Nearly all of the mythological pageantry of Masonry is inherently tinged in, if not outright copied from, Kabbalistic and Talmudic symbology: its adaptation by this exclusively Jewish fraternity was easily and readily made. Wilhelm portrays its structure very differently however:

The fact that the name of the first lodge was entirely secular and referred exclusively to its location, New York, can be taken as an unambiguous step toward distancing the order from the influence of traditional religiosity.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, Pg. 28

Yet for all the secular appearance, the organization’s pageantry and name — Sons of the Covenant — reveals its true character: a self-consciously ethnic and religious community adapted to modern civic forms.

Their stated aims were ambitious. As the first constitution declared:

B’nai B’rith has taken upon itself the mission of uniting Israelites in the work of promoting their highest interests and those of humanity; of developing and elevating the mental and moral character of the people of our faith; of inculcating the purest principles of philanthropy, honor, and patriotism; of supporting the science and art; alleviating the wants of the victims of persecution; providing for, protecting, and assisting the widow and orphan on the broadest principles of humanity.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, pg. 28

As we will find out, their endeavors have not solely been relegated towards these anodyne ends, and indeed, much like its gentile counterpart, such philanthropy is often used as a convenient shield to deflect criticism away from the inherently religious and political actions of the Order. In practice, B’nai B’rith initially concentrated on mutual aid, especially helping members in financial distress, providing death benefits, and supporting widows and orphans — indispensable functions for a growing immigrant community.

Within a few years, B’nai B’rith began to grow steadily. By 1851, the order counted twelve lodges, with an aggregate fund of $19,134.23 — some $800,000 in 2025 — and had disbursed over $1,100 in aid to needy members that year alone. Yet even in this early period, the vision expanded beyond simple mutual aid. Structurally, the Order evolved quickly as well. By 1852, B’nai B’rith had established the system of districts, with each district encompassing lodges in different regions, each semi-autonomous but united under a Grand Lodge. Again, the echoes of Masonic governance are unmistakable.

Philosophically, B’nai B’rith presented itself as both American and Jewish. The notion of a “Jewish civil religion,” blending universal ethical ideals with Jewish identity, reflected the aspirations of its founding generation. As Wilhelm frames it:

…B’nai B’rith succeeded in firmly anchoring a Jewish civil religion within the more general American civil religion and continually synchronizing it with the central parameters of American identity.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, pg. 5

Yet as we will cover in later chapters of this series, this synthesis was never purely assimilationist. As B’nai B’rith’s constitution makes clear, the order was, from its inception, an instrument for advancing its communal interests.

Indeed, the organization’s very first foray into public affairs shows this reality. In 1851, B’nai B’rith marshalled opposition against a treaty between the United States and Switzerland. In the first historical account written on the Order (with an effusive preface penned by one Robert F. Kennedy, Sr.), B’nai B’rith member Edward Grusd recounts:

B’nai B’rith first spoke out on a public issue in behalf of the Jewish people early in 1851, when a treaty was pending between the United States and Switzerland. It was learned that several Swiss cantons had laws forbidding Jews to live there, and that the pending treaty would exclude Americans of the Jewish faith from its benefits in those cantons. Dr. Sigismund Waterman, who a decade later was to become president of B’nai B’rith, wrote letters of protest on behalf of the Order to Secretary of State Daniel Webster and to Senator Henry Clay. Webster and Clay both assured him they would take action against the outrage.

— B’nai B’rith: The Story of a Covenant, Ch. 2

Although their efforts were ultimately undermined — mysteriously neutralized by unnamed “other parties” — the episode illustrates that B’nai B’rith always viewed itself as a defender of Jewish rights internationally, not merely a domestic fraternal society.

“The beauty and pride of Masonry is its universal character, its tendency to fraternize mankind, and its being free from the elements which have been ever the efficient causes of hatred, persecution, fraud, and rude barbarism.”

— Dr. Isaac M. Wise, The Israelite, August 17th, 1855

By the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, B’nai B’rith was still relatively small compared to its later growth.

Nevertheless, the order had successfully transplanted the fraternal model of European Masonry into American Jewish life, consciously modified it for ethnic self-consolidation, and began the long process of transforming itself into an outspoken vehicle of ethnic communal power. The American Civil War marked a period of both disruption and opportunity for B’nai B’rith. Though the fraternal order was still relatively young and regionally concentrated, its membership reflected the complex loyalties of American Jewry. Many B’nai B’rith members took up arms, some for the Union, others for the Confederacy.

Edward Grusd records that members of B’nai B’rith lodges enlisted in substantial numbers:

From District No. 1, headquartered in New York, came repeated reports during the war years of members volunteering for the Union Army. Individual lodges suffered losses in manpower, but the sense of patriotic duty, North and South, remained strong.

— B’nai B’rith: The Story of a Covenant, Ch. 3

Among notable examples, members of New York’s Maimonides Lodge — one of the early lodges of B’nai B’rith — enlisted at high rates in Union regiments. While the war strained operations, particularly in the South, communication with the central Grand Lodge would remain largely unimpeded.

In December 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant issued his infamous General Order No. 11, expelling all Jews from the military department under his command, which included Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky. The order stated that “the Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department… are hereby expelled from the department within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.” Grant’s directive accused Jews collectively of participating in illegal trade — specifically in smuggling and black-market cotton. Enforcement was sporadic, but in several areas, notably Paducah, Kentucky, some families were forcibly removed from their homes under military supervision.

The reaction to the order was swift. Jewish leaders, including Rabbi Isaac Leeser, of the Reform sect, as well as prominent members of B’nai B’rith, protested directly to President Abraham Lincoln. After pressure from within Lincoln’s administration and lobbying efforts from Jewish citizens and civic allies, Lincoln rescinded Grant’s order on January 4th, 1863. Though short-lived and largely unenforced, General Order No. 11 has become a foundational grievance in American Jewish political memory.

After 1865, B’nai B’rith entered a rapid period of growth. The Order survived intact, and the postwar years brought a new phase of expansion. District lodges multiplied as Jewish communities spread westward with American expansion. By 1870, B’nai B’rith had established active districts across the Northeast, Midwest, and California. Cornelia Wilhelm notes:

B’nai B’rith’s pattern of expansion closely followed Jewish migration routes, creating a network of lodges in cities and towns wherever sufficient numbers of German Jewish immigrants had settled.

— The Independent Orders of B’nai B’rith and True Sisters, Pg. 40

The postwar period also marked a subtle but decisive shift in the Order’s mission, one which would bear enduring consequences.

Externally, B’nai B’rith maintained the pose of a universalist fraternal order. However, critics, such as the controversial John Merrick Church, noted its ethnic particularism by the early 20th century (emphasis mine):

A reader of the official organ of B’nai B’rith, “B’nai B’rith Magazine, A National Jewish Monthly”, who knows the radical movement in detail, cannot but be struck by the consistent praise of Socialists and Communists in its columns, the complete absence of criticism of Red revolutionary activity, the virulently anti-Christian sentiment and activity of the Order, and the huge funds at its disposal to purchase the services of preferably Gentile religious fronts to defend such Jewish activities.

They are even securing Fundamentalist Christian ministers as their propagandists, which is more clever on their part than on the part of the sincere Christian who unwittingly betrays his Lord for thirty pieces of silver.

— B’nai B’rith: An International Anti-Christian, Pro-Communist Jewish Power, Pg. 1

Church’s assessment, while strident at times, points to an undeniable trend: B’nai B’rith had long abandoned any pretense of neutral fraternalism.

Beneath its Masonic exterior of brotherhood and benevolence, the Order began pursuing a new goal: the use of legal threats, social pressure, and economic retribution to suppress criticism and regulate American public discourse. The tactic was simple but effective: dissent, slander, or even unapproved opinion would not be debated — “requests” would be made to offenders, whom, if not compliant, would be punished. Businesses would be boycotted, reputations destroyed, careers ended. In this respect, B’nai B’rith pioneered methods that would only become mainstream generations later under the modern euphemism of “cancel culture.”

As the Leo Frank case would soon demonstrate, B’nai B’rith’s focus was no longer simply fraternal solidarity or cultural preservation, but the mobilization of political power to suppress its foes and exonerate its friends. Not only would the case lead to the forming of the B’nai B’rith affiliated Anti-Defamation League, it would forever shatter B’nai B’rith’s self-image as defenders of innocence against “mindless” hatred.

In founding the ADL in 1913, B’nai B’rith formalized a shift decades in the making: the transition from mutual aid to aggressive political lobbying, legal warfare, and narrative control.

Continued in Part II…

“B’nai B’rith will surely be in the forefront of that struggle for justice and equality, as they have led us so often in the past.”

― Robert F. Kennedy, Sr., B’nai B’rith: The Story of a Covenant

Further Research