It’s One of the Most Powerful Conspiracy Theories in the World. There’s a Reason So Many People Believe It.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

When No Other Land won the 2025 Academy Award for Best Documentary for its depiction of life in the occupied West Bank, some in the Hollywood audience sat silently in protest. Far from the ceremony, an insidious narrative about the movie was already taking hold.

“Hollywood gave a Pallywood mockumentary an Oscar,” declared YnetNews, calling the film a “dangerous fable” and accusing its co-directors of staging confrontations and manipulating footage. Israel National News published an article titled “Pallywood Propaganda Wins an Oscar,” written by a spokeswoman for an Israeli pro-settler NGO, who wrote that the film is “an extreme anti-Israel concoction” designed to manipulate Western audiences. In a separate op-ed in the Wrap, critics demanded that the academy rescind the Oscar, accusing the filmmakers of “outright falsehoods” and “emotional manipulation.” The message was clear: The movie was “Pallywood propaganda on steroids.”

The term Pallywood—a portmanteau of Palestine and Hollywood—stems from a long-standing claim that Palestinians fabricate their suffering for cameras, using actors, dolls, or staged scenes to smear Israel. It offers an all-purpose, ready-made excuse to dismiss even the most well-documented atrocities, sowing just enough doubt to ignore Palestinian suffering entirely.

This conspiracy has been around for years, but mentions of Pallywood spiked dramatically after Oct. 7, 2023, far surpassing previous peaks for the term during past Israeli military offensives in Gaza and the West Bank. Beyond Israel, Pallywood has gained traction in right-wing circles worldwide, particularly in the U.S. and India. One of the most grotesque examples came in December 2023, when a wave of pro-Israel accounts—including the official @Israel handle, the Jerusalem Post, and influencers like Ben Shapiro—amplified the claim that a grieving Palestinian man, seen in a widely shared video cradling his killed baby grandson, was faking it. “Hamas accidentally posted a video of a doll (yes a doll),” the @Israel account wrote in a post that was viewed more than 1.3 million times. Others—including StopAntisemitism, Hen Mazzig, and Yoseph Haddad, echoed the claim to millions more. “Pallywood 🤣,” delighted Eli David.

In truth, the baby, 5-month-old Muhammad Hani al-Zahar, had been killed in an Israeli airstrike. The supposed “doll” these accounts amused over was his body. The Jerusalem Post eventually retracted its article. But by then, the damage was done. The lie didn’t need to hold up under scrutiny—it confirmed what many were already primed to believe.

These claims have proliferated in recent months, even as the horrors of the war in Gaza have been increasingly difficult to dispute following the often-deadly work of journalists and health care workers who have continued to report what’s happening on the ground. I spoke to some of those people—and also to the people who aren’t so sure that there aren’t Palestinian ruses afoot—to understand the seductive and enduring power of the conspiracy that, more than ever, seeks to mask the reality of the carnage in Gaza.

When I met Richard Landes in New York, he had just arrived from Israel, where he also keeps a home. Dressed in a wide-brimmed hat and walking with a cane, he looked like an aging adventurer, eager to deliver to me his theory about media deception and how Palestinian propaganda had “evolved” into what he calls “Pallywood 3.0”—a supposedly industrialized version of the staging of tragedies he believes he uncovered decades ago.

Few have done more to promote the Pallywood myth than Landes, a medievalist and historian of apocalyptic movements who coined the term. In his most recent book, 2022’s Can “the Whole World” Be Wrong?, he argues that Western journalists are unwittingly reporting Palestinian propaganda as legitimate news (a phenomenon he calls “lethal journalism”), rendering them complicit in spreading antisemitic narratives under the guise of human-rights reporting. The book expands on the idea of Pallywood as an intricate, evolving system of staged deception designed to manipulate global opinion against Israel.

Over coffee, Landes traced his convictions back to the case of Muhammad al-Durrah, a 12-year-old Palestinian boy shot and killed in 2000 at Netzarim Junction, in Gaza, an event caught on film and broadcast worldwide. Landes said he was immediately suspicious of the footage. He described to me his benevolent curiosity, watching hours of raw video from the scene and discovering what he believes were signs of staging—injured men getting up, ambulances whisking away seemingly unharmed people. He fixated on the final frames, when al-Durrah, moments from death, appears to move his arm.

“The last time you see him in a clip taken by the cameramen, he is alive,” he said. “He’s lying stretched out; he’s got his right hand over his eye, not clutching his stomach, where he was allegedly hit with a fatal wound. And then he slowly lifts up his elbow and peeks out at the camera and then slowly lowers the elbow. And it’s so obvious that the journalist who ran the story literally cut that scene so that people wouldn’t see it. I don’t think he was killed.” He remains convinced that Palestinian camera operators, medics, and bystanders were all in on a kind of elaborate theater. “The boy who’s being carried to the funeral is not the same as the picture of the boy from the family of Muhammad al-Durrah,” he said. (What actually happened that day has been the subject of extensive revelations and questionable reversals for decades; al-Durrah’s family, and the people who witnessed the events, maintain that he was killed by Israeli soldiers.)

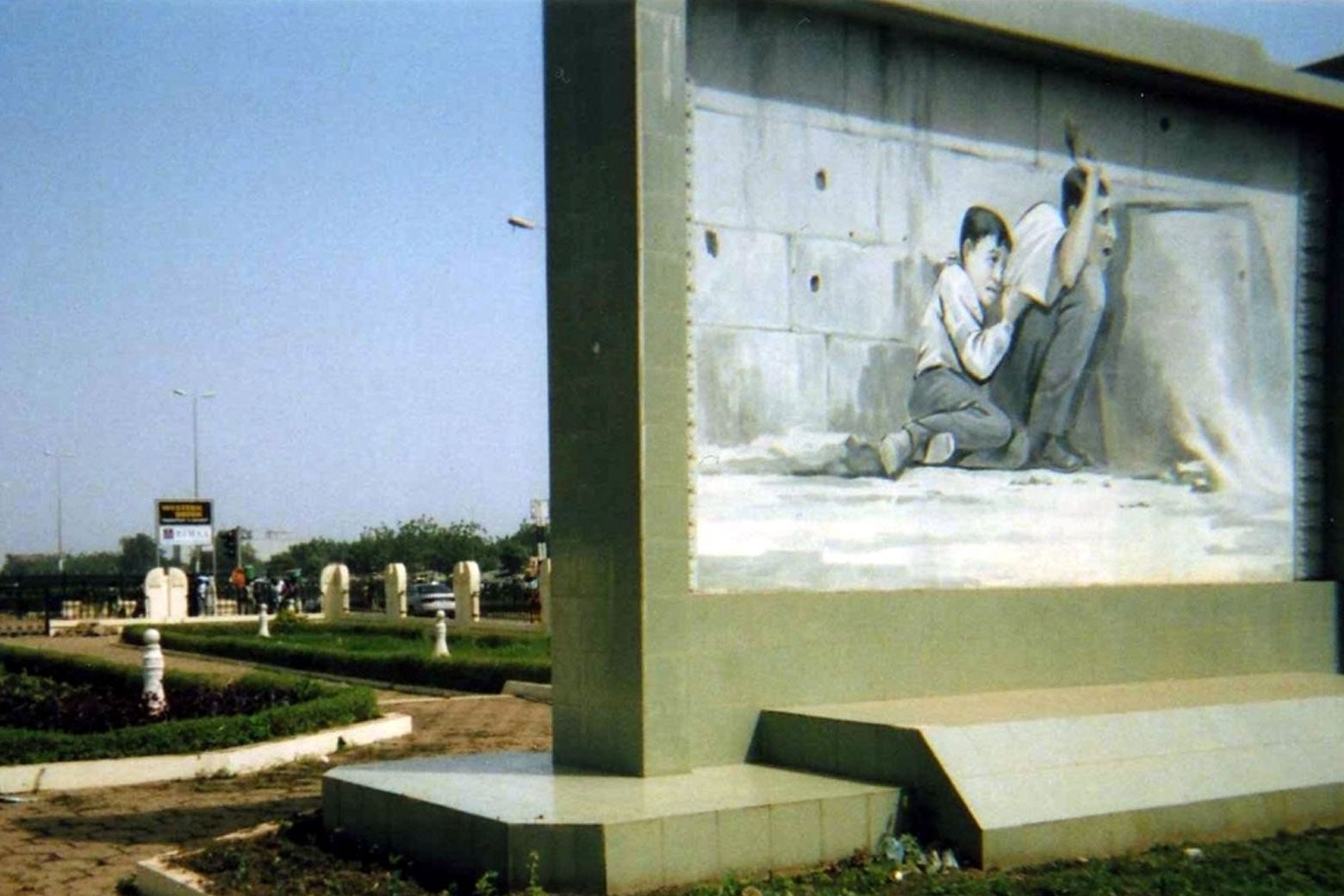

PetterLundkvist at English Wikipedia

For Landes, this moment was foundational. He argues that Palestinians are waging war with empathy. “They got to fight back somehow. They don’t have the weapons, but a picture is worth a thousand bullets,” he said. “They’re manipulating the compassion of Westerners so that they can get a massive response of anger at Israel, force her to a ceasefire, and thereby spare Hamas so Hamas can once again start a round in which they draw Israeli fire onto their own civilians.”

It became a self-reinforcing logic: In his view, the more compelling the image, the more likely it was a deception.

Landes told me that nearly every clip from Gaza and the West Bank contains clues. “You’re an Arab, right?” he asked me. “Women weep openly, but is it common for men to do the same in grief? Ask around. In many cultures, especially warrior cultures, men don’t display emotions like sorrow. They might cry in rage but not in despair. And yet, in these videos, you see men weeping dramatically.” He pointed to Gazawood, a crowdsourced website and X account that compiles what it claims are Pallywood slipups—supposed bad edits, recurring actors, makeup mistakes. The account frequently shares videos of dead Palestinian babies, speculating that they might be fake. “If you pause the footage and look closely, you’ll see other people in the background who were smiling at the performance,” Landes added, referencing videos like this one.

Landes continues to monitor footage from Gaza closely. In a recent Substack post, he scrutinized a video showing the immediate aftermath of an Israeli airstrike that hit a 13-year-old boy, Mohammed Salem, and a secondary strike on those who came to his aid that killed Salem and a 14-year-old boy and wounded 20 others. Though the Washington Post verified the video’s authenticity and the Israeli military acknowledged the strikes, Landes argues that a lack of visible injuries and people reacting before the explosion proves that it was staged.

I pointed out that many so-called examples of Pallywood have been debunked—like videos supposedly showing Arab children having makeup applied to fake injuries, recordings that are actually behind-the-scenes footage from films or commercials. But Landes insisted that his broader point still stood: “I’m not saying that every claim of Pallywood is fairly accurate. I do think that there are significant numbers that are accurate.”

Though he stops short of denying the destruction in Gaza outright, Landes believes that the world is slowly catching on. He cites past cases—like the 2004 Gaza beach bombing, in which four Palestinian children were targeted by Israeli naval strikes while playing soccer, and for which he claims that Hamas land mines were actually responsible—as examples of how initial narratives shape public perception long before facts are verified. Even when he concedes that Israeli forces may commit atrocities, he argues that Palestinian exaggerations, and the willingness of Western journalists to relay them, are what truly fuel the cycle of violence.

As Israel bans foreign journalists from entering and reporting freely in Gaza, I asked Landes, what hope do we have to verify information in the way he seeks? “It may be that you can’t. It may be that you have to recognize that,” he told me. “The journalist is there to report as accurately as possible. And if you can’t report accurately, you don’t just incredulously run with any information you get from people who are clearly warriors with their pens and their cameras.”

Laila Al-Arian, an Emmy- and Peabody-winning investigative journalist and executive producer of Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines, has spent the months since October 2023 reporting on Gaza. Her feed is flooded with footage of bombed homes, bloodied children, frantic rescue efforts—as well as accusations that it’s all fake.

“It’s everywhere on my Twitter,” she told me. To her, the concept of Pallywood is no more credible than the “crisis actor” conspiracy theories used to deny mass shootings in America, like the one at Sandy Hook. “Facts don’t matter. They’re inventing stories to discredit what’s right in front of them: suffering, atrocities, death,” she said.

Al-Arian, who is Palestinian American, said the “Pallywood” label has followed her work for years but has intensified with the war in Gaza. The assertion that Palestinians are unreliable narrators of their own stories deeply frustrates her. “Journalists aren’t really journalists. Doctors aren’t really doctors. Rescue workers aren’t really rescue workers. It’s all about delegitimizing Palestinian voices,” she said. “If you paint Palestinians as irrational, obsessed with martyrdom, you shift the conversation away from settler colonialism, land theft, ethnic cleansing.”

In her work, she often has to contend with the effects of this doubt; while Israeli lives are consistently portrayed with sensitive compassion in Western media, Palestinians are often denied that. “Israeli snipers who shoot children are still given the benefit of the doubt,” she said. The world sees only a fraction of what’s really happening, she told me: “Forget Pallywood. The real tragedy is how much we don’t see. Journalists are being killed, their equipment destroyed. What makes it out is just a sliver of reality.”

Even so, it wasn’t hard to find journalists in the region who see things differently. For reporters like Al-Arian, there is a flood of raw footage: families pulling bodies from rubble, lifeless and bloodied children in the arms of dispirited parents. But in pro-Israel circles, those same platforms are filled with selective clips framed as evidence of Palestinian trickery—a “corpse” shifting under a shroud, civilians eating desserts amid a food shortage. Each is fodder for the Pallywood narrative.

“Do you know Mr. FAFO?” Ruthie Blum, an Israeli journalist, former Jerusalem Post editor, and former adviser at the office of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, asked me. She was referring to Saleh Aljafarawi, a Palestinian musician turned citizen journalist who now documents Israeli airstrikes in Gaza in real time. “Apparently he’s a well-known actor in Palestinian circles,” she said, “who’s appeared in several clips playing the part of a wounded Palestinian, all bloodied up, and, in other footage, having makeup applied to him in what looks like a makeshift studio.”

Aljafarawi was given the FAFO nickname—short for “Fuck Around and Find Out”—after pro-Israel accounts circulated footage of him early on in the war cheering on Hamas rockets, juxtaposed with videos of him weeping amid Gaza’s devastation. He quickly became a central figure in the Pallywood conspiracy. His image is often used to suggest that Palestinians are staging their suffering—even when the videos shown aren’t of him. Multiple news organizations have debunked these claims. Yet the conspiracy persists.

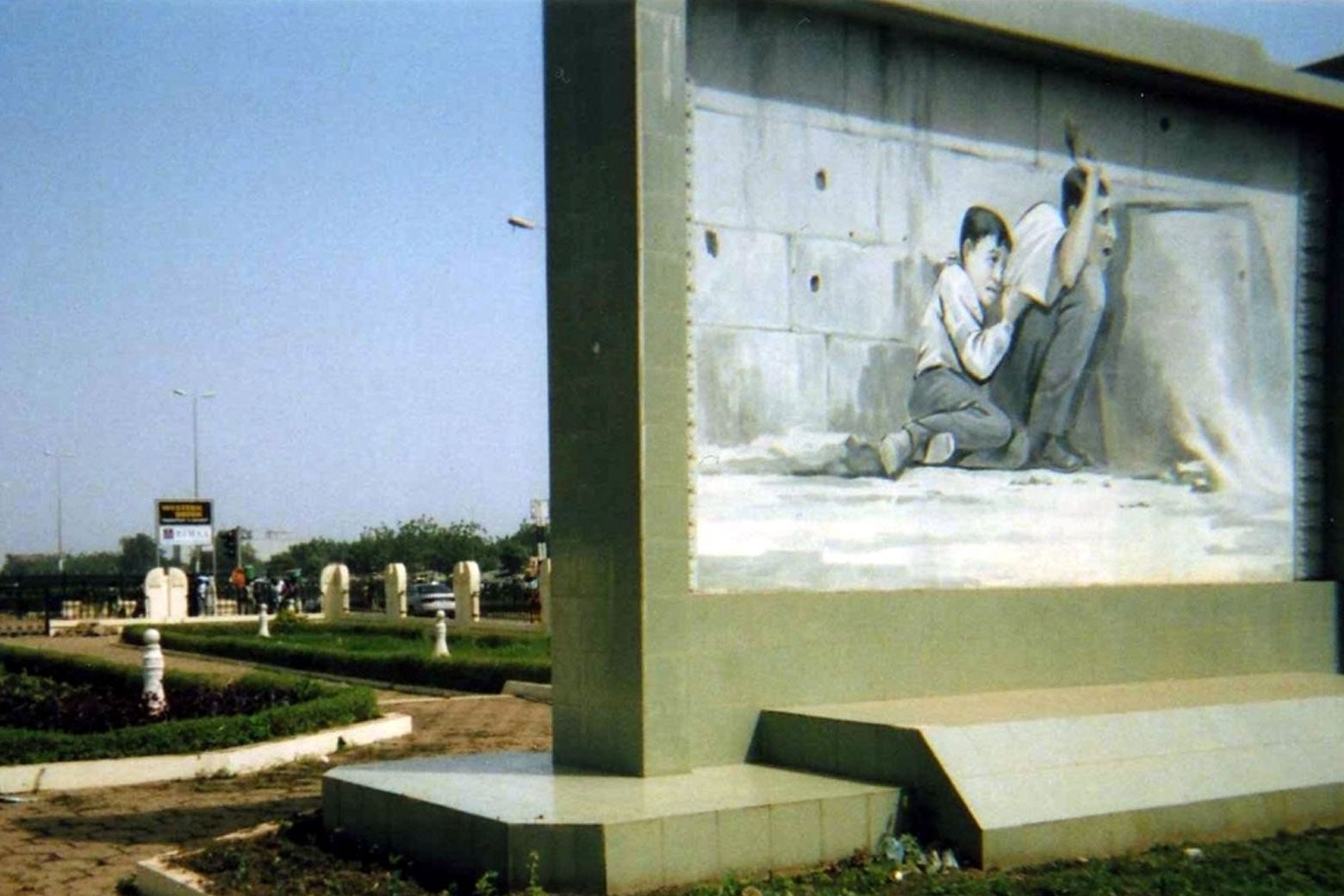

Abdallah F.s. Alattar/Anadolu via Getty Images

Blum is certain Pallywood is real, at least in part. “There have been many, many videos,” she said. “You’ll see a row of dead bodies covered in sheets, and then one of them lifts his arm to check his phone. Or there’s this other one, with a father weeping over his supposedly dead kid, and then the kid starts scratching his foot. He’s a little kid, so he couldn’t keep still.”

She told me her son, a soldier in the Israeli military, barely survived his deployment in Gaza. And she insists that the images perpetuate a culture of violence within Palestinian society.

“It’s used to persuade children to become martyrs for Allah,” she said. “They say: ‘Look at this dead boy—you should aspire to that.’ That’s what makes it different from other kinds of propaganda. This is why Palestinian children are such victims of their society—because they are taught to idolize not only killers but killers who died in the process of killing.”

Blum doesn’t deny that real suffering is happening in Gaza. But she praised the Israeli army’s rules of engagement and argued that even if any of the images are authentic, “every death in Gaza is on Hamas’ hands.”

Because it’s an English term, most Palestinians in Gaza have never even heard of Pallywood. Most Israelis don’t use it either. But Tom Divon, a researcher at Hebrew University specializing in digital culture, told me that the idea is much more powerful—and deeply ingrained—than the term itself. “No content from Gaza has the chance to stand as evidence of truth in the current climate, where we are conditioned to search for the fake. We wait for the injured girl to stand up, laugh, and reveal the lie, because we’ve been trained to see Gaza through a lens of suspicion,” he said. “It’s a way to cope. Truth, in its full force, is overwhelming. Denial offers some relief.”

Since Oct. 7, Divon said, skepticism around Palestinian suffering has evolved. Where the term Pallywood was once invoked to suggest manipulation, many now simply look away: doubting death tolls, dismissing the scale of destruction, or otherwise accepting outright that mass civilian casualties are an acceptable cost of a just war.

“Gaza’s inhabitants are objectified, reduced to numbers or blurry concepts. The media rarely shows unfiltered images or personal stories, because doing so would be too confronting for most viewers,” he said. That distancing, he noted, predates the current war. Israeli mainstream media has long excluded humanizing perspectives of Palestinians, including Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, he said.

These days, when Palestinians post TikToks documenting life in a locked-off war zone, many Israelis begin from a baseline of disbelief. “ ‘Why are they baking cakes if they’re starving?’ ‘How are they making polished videos if they’re under siege?’ ” Divon said, explaining the reasoning. The rise of A.I. has only deepened public skepticism, making it feel increasingly plausible that any image or video, no matter how realistic, could be fake.

For Divon, Pallywood is less a conspiracy theory than a psychological defense mechanism. Within Israeli society, he said, it’s easier to imagine Palestinian suffering as unserious or exaggerated than to grapple with what the Israeli military is inflicting. “To them, it’s all lies. Why? Because acknowledging it as truth would shatter us,” he said. “How long until we look back and recognize that our mechanisms of denial were too strong, that we ignored the truth?”

Maytha Alhassen, a historian who studies media and national identity, sees Pallywood not as a uniquely Israeli phenomenon but as part of the mythmaking process in many nations. The U.S. legend of the “great American liberator” was invoked for decades to rationalize the country’s wars abroad, she said. She points to the 2022 documentary Tantura, which reveals how, decades ago, Israel erased evidence of massacres while promoting the idea that Palestine was “empty land,” a narrative essential to its national origin story.

The emotional investment in these beliefs, she argues, makes confronting the reality of Israel’s founding—displacement and devastation for Palestinians—almost impossible for many. “To question it is to shatter a core piece of identity,” she said. This, she believes, is why accusations of Pallywood gain traction. They’re meant not just to discredit Palestinian suffering but to preserve the psychological comfort of those invested in the status quo: “When your identity is formed around a nation-state, it requires so many acrobatic maneuvers to maintain it.” For many, Alhassen said, facing the reality of what’s happening in Gaza means facing something personal. “Either you confront that truth or you protect the dream. To accept the horror would be to shatter something at your core.”

While reporting this article, I spoke to many journalists and doctors on the ground in Gaza who told me that the horrors they’d witnessed were beyond question. Tanya Haj-Hassan, a pediatric intensive care physician, described treating a child whose body had been mangled by an Israeli bulldozer that ran over her tent while she slept. Despite her best efforts, the girl died in agony. Journalist Mohammed Mhawish recounted surviving an airstrike: His home was bombed, entombing him, his wife, and their 2-year-old son. Though several relatives and neighbors sheltering with them were killed, Mhawish and his family were pulled out alive by neighbors, bloodied but breathing. He resumed reporting shortly after recovering from his injuries. Stories like these are so wrenching, so unbearable, that it becomes easier to understand why some would rather call them fake—“Pallywood”—than confront what they reveal.

Combing through these examples, I thought back to my conversations with Landes. I wondered if he had any thoughts on No Other Land, filmed from 2019 to 2023 in the West Bank by, as it happens, a team of both Israeli and Palestinian filmmakers. He dismissed it outright. “The ‘documentary’ is a classic expression of Palestinian propaganda,” he told me. That the film could win an Academy Award, he said, was “testimony to the collapse of professional standards before the demands of political correctness.” Then he added: “If Palestinians expended a fraction of the energy and creativity they dedicate to maligning Israelis and playing victim on building a future for themselves, this would not be a forever war.”