Understanding what drives conspiracy theories, in the context of COVID-19 in India and political beliefs

When believing in conspiracies also makes you believe that you are unlikely to get the virus, it is indeed dangerous.

The more conservative you are, the more you are likely to conspiratorially blame powerful others for the pandemic. Illustration © Adrija Ghosh for Firstpost

Have you heard that the government created the COVID-19 pandemic to hide the impending economic crash? If you have, and believed this, you have fallen prey to a conspiracy theory.

pandemic to hide the impending economic crash? If you have, and believed this, you have fallen prey to a conspiracy theory.

Conspiratorial thinking usually makes one believe that someone, usually a powerful “other”, is hiding something important about an otherwise unexplained situation, from them. In the context of the coronavirus , we still do not know for certain what the origin of the virus is, and therefore, many of us would believe a conspiracy related to COVID-19

, we still do not know for certain what the origin of the virus is, and therefore, many of us would believe a conspiracy related to COVID-19 . This is especially true when it comes to understanding the effects of the virus, specifically the long-term effects. We could end up believing many sources, ranging from medical experts to WhatsApp messages.

. This is especially true when it comes to understanding the effects of the virus, specifically the long-term effects. We could end up believing many sources, ranging from medical experts to WhatsApp messages.

What causes one to believe in a conspiracy? Usually, a heightened sense of reference to yourself and a preoccupation with how others are thinking about you. What this means is that you may be paranoid (non-clinically) that others, especially powerful others, are malevolent. In simpler terms, you may be worried about yourself being the intentional target of a more powerful person or entity, such as the “government”. This primarily stems from a distrust of institutions, which also leads you to believe that you are at greater personal risk from their actions. It also comes from a rigid way of thinking — particularly from a difficulty in believing that, in general, things may occur randomly.

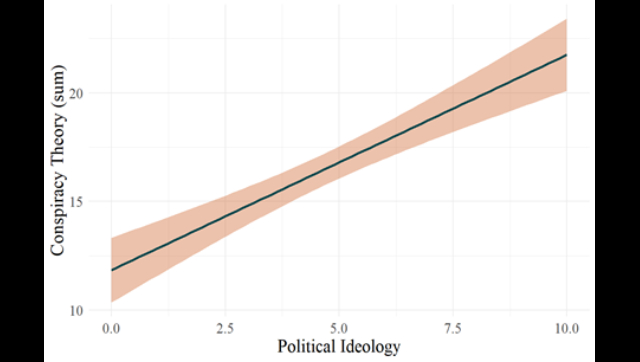

Usually, such rigidity is seen in the extremes of political ideology in a number of Western countries; however, we lack such data in India. In an ongoing study, we wanted to test this prediction: Does political ideology actually predict conspiracy beliefs, particularly with respect to a number of conspiracy theories pertaining to the coronavirus ?

?

We found that those who were more Right-leaning were more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. That is, the more conservative you are, the more you are likely to conspiratorially blame powerful others for the pandemic. We found this to be true for each of the “powerful” groups we studied: scientists, interest groups such as pharma companies, as well as the government. The government was blamed for two reasons: for creating the pandemic to cover up an economic crash, and to try to increase authoritarianism.

Previous research in this area has found that when justifications are made based on one’s ideological biases, they also reinforce identity threats. We usually think that our groups, (for example, our religion, our caste, our political parties) are more positive, and we often degrade those outside our groups to sustain our beliefs about our group’s superiority. We even go out of our way to keep up this belief, so as not to feel bad when facing an identity threat. In the context of the pandemic, we have seen how certain religious and/or occupational groups, particularly those that conservatives believe to be outgroups, were especially targeted and have been touted as the “cause” of the spread of the virus.

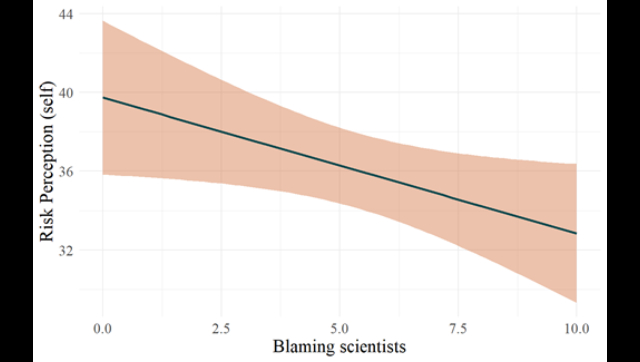

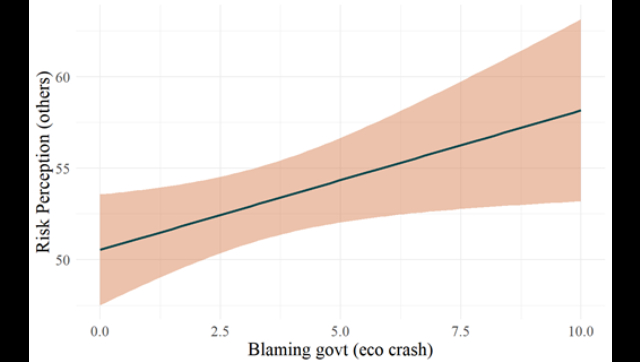

However, conspiratorial blame itself is not the core of the issue. Blaming others for the virus also made the respondents believe that they are not at risk of getting infected. When respondents believed that scientists were likely to be the cause of the virus, they believed that they were at lower risk of contracting the virus. Further, believing that the government was trying to hide an economic crash also led those leaning towards the Right to think that other Indians were at a higher risk of contracting the virus.

When believing in conspiracies also makes you believe that you are unlikely to get the virus, it is indeed dangerous. When one thinks that the scientists made up the virus, and therefore, they are not at risk, their own behaviours to curb the virus reduce. This makes one engage in risky behaviours such as not social distancing, and gathering in crowded public places.

People who were Right-leaning also thought that the average person in India was at a higher risk of contracting the virus, due to their belief that the pandemic was an exercise in hiding an economic crash. This is pretty similar to previous research, which also indicates that in scenarios where another person is at a risk of physical harm, we tend to be more risk-averse. This might be because we think others are less risk-averse, possibly because we think we are better than the average individual in accurately assessing risks, and others are poorer than us in the same regard.

It is imperative that we understand that sometimes, either due to the news and other content we are consuming, we might believe falsehoods or half-truths. We must engage in critical thinking, especially as the pandemic rages on, with respect to the risks we are willing to take for ourselves, but especially for others.

Arathy Puthillam is with the Department of Psychology at Monk Prayogshala, a not-for-profit research organization based in Mumbai. Her research interests include social, moral, and political psychology and tries to answer the question how do our groups affect us. She tweets @WallflowerBlack