Why People Fall For Conspiracy Theories

Think of a conspiracy theorist. How do they see the world? What stands out to them? What fades into the background? Now think of yourself. How does the way you see things differ? What is it about the way you think that has stopped you from falling down a rabbit hole?

Conspiracy theories have long been part of American life, but they feel more urgent than ever. Innocuous notions like whether the moon landing was a hoax feel like child’s play compared to more impactful beliefs like whether vaccines are safe (they are) or the 2020 election was stolen (it wasn’t). It can be easy to write off our conspiracy theorist friends and relatives as crackpots, but science shows things are far more nuanced than that. There are traits that likely prime people to be more prone to holding these beliefs, and you may find that when you take stock of these traits, you aren’t far removed from your cousin who is convinced the world is run by lizard people.

Flying to conclusions

JOEY ELLIS

Let’s begin our tour of cognitive fallacies by going bird-watching. Picture, if you will, avid bird-watcher Fivey Fox at their two favorite spying spots. In one habitat, there are more cardinals than bluebirds — a 60:40 ratio — so Fivey calls that habitat “Big Red.” In the other habitat, “Big Blue,” there is an opposite ratio of bluebirds to cardinals (60 bluebirds, 40 cardinals).

In the interactive below, you initially can’t see which spot Fivey is bird-watching in, but you can see what bird they spot. After each sighting, Fivey notes the bird in their notebook, and then you decide whether you have seen enough to guess the correct habitat or you’d like to see more birds. Have a go!

Did you get it right? Actually, who cares! I am more interested in how you made your decision.

That game measures a trait known as the jumping-to-conclusions bias. If you made your choice about the habitat after seeing just one or two birds, you demonstrated that trait, even if you made the right decision. The bias indicates a tendency to make up one’s mind about things quickly, often with very little evidence. One study found that people with this bias were more likely to endorse conspiracy beliefs than people without it, and it’s also been found to be correlated with harboring delusions.

It’s not surprising that someone who tends to make up their mind about something after reviewing very little evidence would be more likely to believe in a conspiracy theory. But if you fall into this category, don’t freak out. It doesn’t mean you’re destined to fall for b.s. the rest of your life. This is only one piece of the puzzle. It’s important to recognize what these kinds of studies can and can’t tell us. Many of the studies only observe a correlation — which we all know does not necessarily equal causation — between certain traits and conspiracy theories. Just because people who believe conspiracy theories are also more likely to have trait X doesn’t mean that it’s trait X that’s making them susceptible — the two might just go together. And even if there is a causal effect, that still doesn’t mean that everyone with trait X will subscribe to a conspiracy theory, or that everyone who doesn’t have trait X is immune to b.s.

“It’s all probabilistic,” said Joshua Hart, a professor of psychology at Union College who has studied the personality traits of people prone to believe conspiracy theories. Hart said when you consider the population as a whole, you can see these traits are correlated with harboring beliefs in conspiracies, but at the individual level, any single trait doesn’t necessarily predispose someone to falling down the rabbit hole. “I don’t think any one of them is going to tip the scale.”

Still, this research is useful and helps us establish a richer picture of who is susceptible to conspiracy theories. Take another exercise, where participants were shown the results of a series of coin tosses.

Patterns can be illusory

JOEY ELLIS

Participants were shown 10 sequences of 10 coins each. After each sequence, they were asked whether they thought the results were random or predetermined, on a 7 point scale (with 1 meaning completely random and 7 meaning completely determined). Take a look at the sequence above: How would you rate that? Click on the footnote to see the answer.<a class="espn-footnote-link" data-footnote-id="1" href="https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-people-fall-for-conspiracy-theories/#fn-1" data-footnote-content="

It’s random.

“>1

This particular exercise was used in a 2018 study to measure something called illusory pattern perception: the tendency to see patterns where there are none. Respondents who believed there was some kind of predetermined pattern to the coin toss sequences were more likely to believe conspiracy theories. The researchers tried a few other methods of measuring illusory pattern perception — such as having participants try to detect patterns in abstract modern art paintings — and found similar results. Another study found this trait is also associated with people who ascribe profundity to randomly generated nonsense statements. Once again, these findings jibe with what you may presuppose about conspiracy theorists: Making connections between unrelated events or symbols is a key marker of many conspiracy theories.

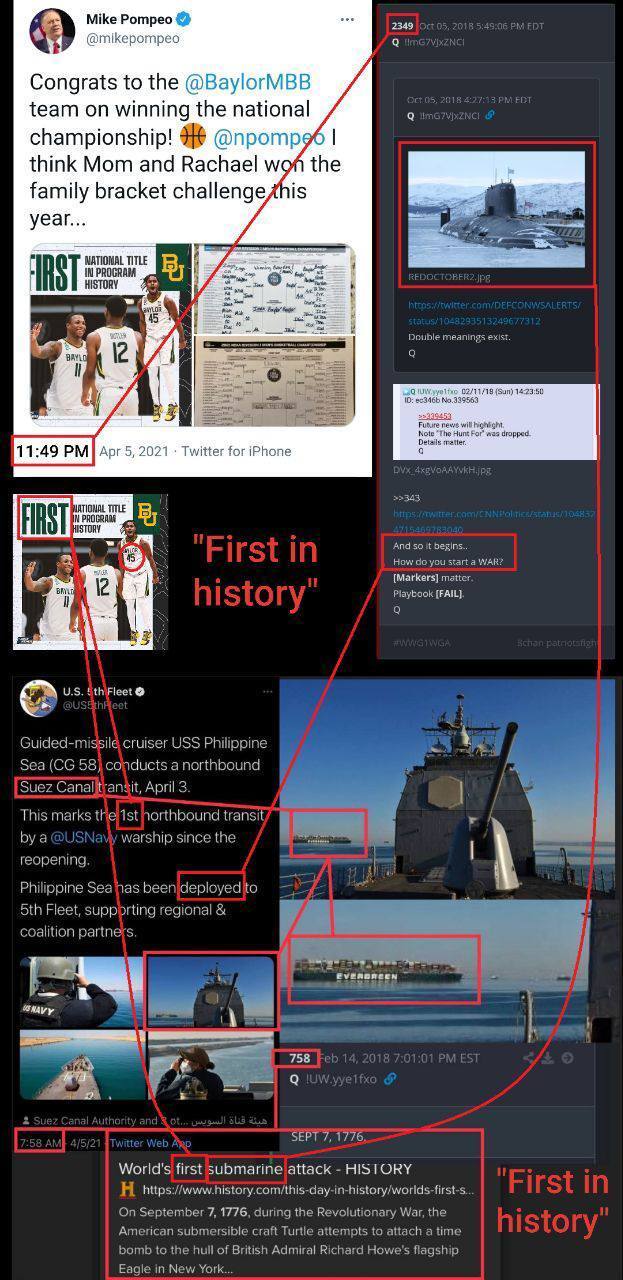

In practice, that might look something like the post below, which was shared in a QAnon Telegram group. It makes many logical leaps to try to indicate that the Ever Given, the ship that was caught in the Suez Canal and which many Q followers believe was transporting trafficked children, is somehow connected to a March Madness tweet from Mike Pompeo, the transit of a Navy warship and a Q post from 2018.

But it’s also a deeply human characteristic to perceive order in chaos. We see rabbits in the clouds and faces in household appliances. Illusory pattern perception is just a heightened version of this universal phenomenon.

Let’s try one more exercise. Answer the following question:

You’re running in a race, and you pass the person in second place. What place are you in?

JOEY ELLIS

There are two likely answers to this question, an intuitive one (first place), and an analytical one (second place). Only the latter is correct, though.

Questions like this are often used to measure whether someone naturally tends to think analytically, to take time to reflect on the information at hand before responding, or if they tend to go with their gut instinct. In multiple studies, people who gave the analytical answer to questions like this — in this case “second place,” — have been shown to be less likely to believe in conspiracy theories, and a 2014 study even found that priming someone to think analytically could reduce their belief in conspiracy theories.

Each of these tasks captures just a drop of the cognitive stew that can make someone more vulnerable to believing in conspiracy theories. But they demonstrate that conspiracy theorists aren’t just loony — many of the traits that can set someone up to believe wild ideas are things all of us are prone to, to some degree. We all have a little conspiracy theorist in us.

Setting up the chessboard

JOEY ELLIS

Cognitive quirks only go so far in explaining why people believe conspiracy theories. It’s also important to consider the environmental factors at play.

“A key element is the extent to which you are exposed to conspiratorial ideas,” said Gordon Pennycook, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Regina who researches reasoning and decision-making. “No one is reflective enough to bat away literally everything that they come across that’s false. Things will seep in if you’re repeatedly introduced to them.”

In the context of modern conspiracy theories, social media plays a significant role in getting these theories in front of the people who might be susceptible to them. Conspiracy theories about the coronavirus vaccine are a clear example. Though social media sites have made attempts to crack down on anti-vaxx content in the last year or so, they flourished in the first place thanks to these sites’ algorithms. And as so many of us have spent more time at home — and online — during the pandemic, our environment has become awash with all kinds of conspiracy theories. Anyone with even the slightest tendency to this kind of thinking would have trouble dodging the rabbit holes.

Research into what leads people to fall down the rabbit hole demonstrates that it’s not as simple as someone being loony — it’s a combination of cognitive quirks and environmental factors. You may even have recognized some of these traits in yourself, and even if you didn’t, you might be able to imagine a scenario where you would. The jumping-to-conclusions bias, for example, exists on a spectrum, and its manifestation can depend on the situation. You may not be willing to guess which habitat Fivey is in after only seeing two birds, but you can probably imagine a scenario where you’d personally feel comfortable making a call with less information. None of us forms every single one of our beliefs and opinions with perfect reasoning and extensive research. Just because we happen to get it right doesn’t mean our brain is doing anything more impressive than those who don’t.

“It’s not like most beliefs are arrived at through some sort of pure logic. The world is not a bunch of Spocks running around deducing everything,” said Joseph Uscinski, a professor of political science at the University of Miami who has studied conspiracy theories. “It’s just not how people operate.”

This might help explain why belief in conspiracy theories is surprisingly common. About half of the American public consistently endorses at least one conspiracy theory. A popular one — that more than one person was involved in shooting former President John F. Kennedy — is believed by around 60 percent of Americans, according to a 2017 SurveyMonkey poll. There’s a good chance you hold a belief that is a conspiracy theory.

Every one of us has a brain that takes shortcuts, makes assumptions and works in irrational ways. The sooner we recognize that, and stop treating loved ones who have adopted conspiratorial beliefs as lost causes, the better we may be at curbing the beliefs that threaten our democracy and public health. We’re all human after all. Well, except for the lizard people.

Art direction by Emily Scherer. Special thanks to Stephanie Mehl for research assistance.