Sparse Voter-Fraud Cases Undercut Claims of Widespread Abuses

Prosecutors across the country found evidence of voter fraud compelling enough to take to court about 200 times since the November 2018 elections, according to a 50-state Bloomberg canvass of state officials.

Republican and Democratic election and law enforcement officials contacted in 23 of the states were unable to point to any criminal voting fraud prosecutions since the November 2018 midterm elections.

Despite the escalating claims from former President Donald Trump of rampant misdeeds, nearly all of the instances found by state officials were insignificant infractions during a timeframe when hundreds of millions of people participated in thousands of elections around the country. Yet, misinformation about the topic has become a driving force of political debate.

Fabricated claims of fraud damages confidence in elections and can encourage partisans to demand that vote totals be changed to the outcome they want, said Edward Foley, an Ohio State University Moritz College of Law professor who studies disputed elections.

If losing political parties feel emboldened to pressure elected officials to undo fair outcomes, then “we have to worry about the capacity to count votes honestly,” he said in an interview. The danger, he said, is “not that there will be any infinitesimal amount of dishonest ballots cast. The real risk is that due to partisan motivations people won’t count them honestly.”

To quantify how much fraud can be documented, reporters with Bloomberg contacted more than 100 officials in all 50 states. All but three states (North Dakota, South Dakota, and Texas) responded. Bloomberg also researched news reports and consulted a voter database maintained by the conservative Heritage Foundation with a goal of ensuring the examination was as thorough as possible.

The reporters asked about criminal charges and convictions for voting fraud between November 2018 and the present.

(Hear more about this reporting project in the On The Merits podcast)

The range of cases pursued included allegations of changing votes in a high school homecoming contest and forging a signature on a ballot for president.

To be sure, there could be more instances, since charging decisions often are left to overburdened local prosecutors who have to focus their limited resources elsewhere. Even so, the findings illustrate a lack of evidence to back up claims of widespread cheating.

Political Affiliations

The information from the states showed that election fraud investigators have no home party.

Republicans hold 26 state attorneys general posts and control 28 secretary of state offices. The states controlled by Republicans in both of those offices reported roughly 59 prosecutions in their states during this period.

Democrats reported 102 prosecutions in the states where they held both of those offices. States where control between these offices is split between Republicans and Democrats—Arizona, Iowa, Maryland, Nevada, and New Hampshire—accounted for 35 prosecutions.

The top state for prosecutions, North Carolina, has a Democratic attorney general and secretary of state. It racked up 32 prosecutions since November 2018, with 24 of those coming out of a U.S. Attorney’s office run by both Trump and Biden appointees.

The prosecutions for voter fraud were literally all over the map.

‘I Was Pissed Off’

After the 2020 general election, a New Mexico man filed a complaint with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, concerned someone had stolen his identity and used it to vote in Seminole County, Fla.

The trail led to the man’s father who, according to a criminal complaint, allegedly told the police he requested and sent in the ballot in his son’s name.

“It was stupid. I was pissed off the way things are going in the country,” the man said, according to the complaint. “I voted but it didn’t make a difference.”

Historically about 30%-40% of the losing side in an election—Democrats or Republicans—claim that elections were “rigged” against them, according to University of Miami political science professor Joseph Uscinski, an expert on conspiracy theories.

That changed this year.

Roughly 61% of self-identified Republicans who responded to a May Ipsos/Reuters poll said they believe the election was “stolen” from Trump.

Photographer: Michael B. Thomas/Getty Images

Supporters of Donald Trump demonstrate outside the Missouri State Capitol building on Jan. 20, 2021.

Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose (R) and Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (D), the co-leaders of the National Association of Secretaries of State’s elections committee, have each said the 2020 general election was the most accurate and secure contest ever held in their states because of the general absence of fraudulent activity.

But “no one cares what election officials say,” Uscinski said in an interview.

(Sign up for the Ballots & Boundaries newsletter to follow the action as states change voting laws and revise political districts.)

The distrust of the election outcome is so high, he said, because “there’s a sustained effort by political and media elites—Trump and his supporters in Congress and in the Trump-supporting media—saying that the election was rigged over, and over, and over again for months on end, if not years.”

From Mundane to Ridiculous

Election doubters often claim that shoddy poll-books and improperly registered voters are committing fraud. Washington Secretary of State Kim Wyman (R) said her experience has been that local officials are vigilant.

For instance, she said, Thurston County, Wash., election officials noticed something unbelievable in a voter registration file about a decade ago: a seemingly normal single-family home address with 19 voters registered to it. “County officials actually physically get in the car and drive out to residences, like, ‘Huh, why are there 19 people living at this house that looks like it’s just a single house,’” said Wyman, who at the time was Thurston County Auditor.

“It was a commune. Single address—looks like a single building on the records—but people were living in tents,” she said in an interview. “That was a very legitimate residence address.”

In Kansas, former U.S. Rep. Steve Watkins(R) was charged with felonies after listing his address as a UPS store for voting in a 2019 election. In a lower-profile race, Ashtabula, Ohio City Council Member Reginald Holman (D) pleaded guilty in 2019 after winning a seat for which he wasn’t eligible—he really lived with his elderly parents in nearby Plymouth Township.

Real examples like those make some election-security skeptics determined to find more.

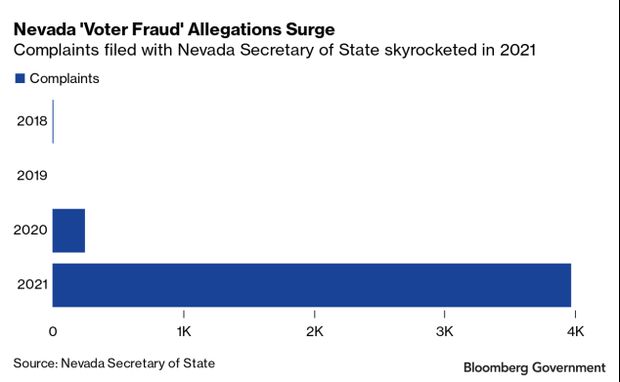

Consider Nevada: After the 2018 midterms the Nevada Secretary of State received four complaints of voter fraud; the office received zero complaints in 2019, 246 complaints in 2020 and at least 3,972 complaints in 2021, Jennifer Russell, a spokeswoman for the office, said in an email.

“We investigate all of them,” she said.

In March, the Nevada Republican Party submitted four boxes of complaints including 122,918 allegations of election irregularities to Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske’s (R) office.

The GOP claimed that 8,842 Nevada voters had registered at commercial addresses—an indication of fraudulent voting patterns, they alleged. However, a statistical analysis of the addresses found 98% were actually addresses where people normally reside (like apartments, mobile home parks, monasteries or dorm rooms), according to a report Cegavske issued in April.

As for the other 2%—she said it’s not illegal to register at a commercial address in Nevada so long as the person lives there, and the complaint lacked proof that voters didn’t actually live at those addresses.

Wyman, who has worked in election administration in Washington State for decades, said her belief in the rule of law is one of the reasons she is a Republican.

“You look at why democracy has worked for 240 plus years and it’s because we have these pillars of democracy, representative government that comes from fair elections people believe the results of, and it comes from the rule of law and it comes from the founding documents,” she said. “And we’re eroding and chipping away at the belief that representative government is legitimate every time we start talking about rigged elections.”

‘Time-Intensive and Expensive’

Even when secretaries of state identify potential fraud, there’s no guarantee that the cases will be a high priority for prosecution.

The average attorney in the nation’s more than 2,300 state prosecutor offices closes roughly 94 felony cases each year, and even small, part-time offices will secure an average of 88 felony convictions annually, according to a national Justice Department survey.

In contrast, the most aggressive voting fraud investigation office in the country, run by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R), logged more than 22,000 staff hours and closed 16 election cases in 2020, according to an investigation by the Houston Chronicle. Paxton’s website said his team is currently prosecuting 43 defendants. He didn’t respond to repeated requests for an interview.

“The investigation of claims of voter fraud are extremely time-intensive and expensive to conduct with most not resulting in any case to be brought forward,” Nelson Bunn, Jr., executive director of the National District Attorneys Association, said in an email. “While an important issue, prosecutors and law enforcement agencies have very limited resources in good times and the impact of COVID and the resulting case backlogs are now straining these offices and broader criminal justice system even further.”

The Ohio Attorney General and Florida’s Secretary of State said they’ve referred dozens of voting fraud cases to local prosecutors since the November 2018 general election, yet neither office knew whether prosecutors had filed charges.

Detecting the ‘Undetected’

In September 2020, the conservative Public Interest Legal Foundation released a report claiming that voter registration files for the 2016 and 2018 general elections were riddled with errors, including nearly 350,000 dead registrants. Based on credit reporting data, the group said it found 37,889 duplicate in-state registrants.

None of the secretaries of state in the 42 states covered by the report reached out to learn more, said Hans von Spakovsky, manager of the Heritage Foundation’s Election Law Reform Initiative and former member of Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity.

“Not only do many of these cases go undetected—the measures aren’t in place to do that—even when there’s evidence of fraud a lot of it doesn’t get investigated,” he said in an interview. “Maybe [secretaries of state] think it would be embarrassing for them to admit that a private organization found all these potential cases of fraud and they don’t want to do anything.”

He held up as an example the U.S. attorney’s office for the middle district of North Carolina, which handled 24 cases alleging unlawful registration or voting by immigrants from November 2018 to the present.

An example of fraud that was prosecuted and changed an election outcome also comes from North Carolina, where a GOP consultant allegedly ran an illegal ballot-harvesting campaign with fraudulently filled out ballots. Eight people were indicted and a 2018 North Carolina congressional race was redone.

In Patterson, N.J., a state judge tossed the results of a 2020 city council race in which nearly a quarter of the absentee ballots were rejected. Four people were charged, including a candidate who was allegedly caught with someone else’s ballot in his coat jacket.

Data Matching

To better address voter registration issues, and tackle many of the problems von Spakovsky and other critics have raised, dozens of states are banding together in the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC).

The private consortium analyzes data such as social security numbers, death records, postal service requests for address changes, drivers license numbers, email addresses, and more to help states determine if voter rolls need to be updated. The group also looks for people registered to vote in two states.

ERIC currently has 30 state members and Washington D.C. At least three more states will join the consortium this year, and by 2024, its databases should cover roughly 80% of U.S. voters, according to David Becker, ERIC founder.

Meanwhile, election officials around the county have sought to show that the procedures they’re using are rigorous and that they can be trusted to resist partisan pressure.

After the election, Trump urged Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) to “find” more votes, and more recently Trump has conflated cleaning up the state’s registration files—a routine process that actually helps prevent possible fraud—with evidence of fraud.

Photographer: Dustin Chambers/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger speaks during a news conference on Dec. 14, 2020.

“We looked into all possible areas of fraud. I was the first Georgia Secretary of State to even look at double-voting. We set up an absentee ballot task force made up of prosecutors to further look into absentee ballot fraud,” Raffensperger said in an interview. “People may not like the results. I understand that—I’m a Republican, I was disappointed, too. But at the end of the day those were the results.”

Raffensperger’s team of 22 investigators armed with guns and law-enforcement backgrounds started looking into double-voting and discovered that roughly 1,000 people had voted absentee in the 2020 presidential primary and then returned to vote in person.

Investigators found that the voters were mostly elderly and confused as they used absentee ballots for the first time during the Covid-19 pandemic. The few that intended to double-vote were referred for prosecution. Roughly 50 other voting fraud cases were referred by the State Election Board in hearings held in February and April 2021.

The state examined claims of 66,000 underage voters, which in reality were properly pre-registered 17-year-olds who didn’t cast ballots. It looked into allegations of 10,000 deceased voter ballots and found two; and found 74 instances of felons voting. All of those possible cases were referred for prosecution, Raffensperger said.

Those who run elections take it seriously, he said.

“Look at your precinct workers—people that you go to church with, that you see at Kiwanis or Rotary or some service organization. They’re the salt of the earth folks that are doing their job,” he said. “And you can trust those folks because they have the most important thing in elections: that’s integrity.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ebert in Columbus, Ohio at aebert@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Katherine Rizzo at krizzo@bgov.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergindustry.com; John Dunbar at jdunbar@bloomberglaw.com