9/11 “Truth”: How believers in the 9/11 conspiracy theory respond to refutations.

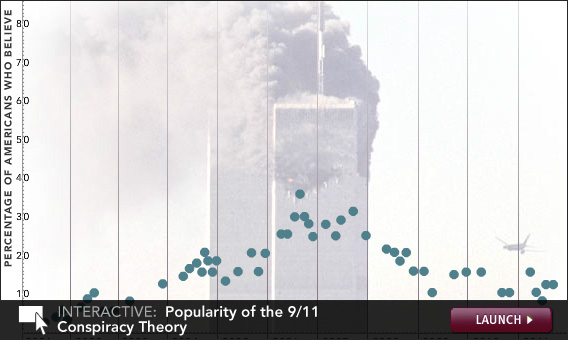

It’s difficult to pinpoint a precise moment when the popularity of the 9/11 conspiracy theory peaked, though it was probably sometime in 2006. In tracking its decline, however, three dates stand out: July 22, 2004, when the 9/11 Commission released its final report; Feb. 3, 2005, when Popular Mechanics published its 5,500-word article dismantling the movement’s claims; and Aug. 21, 2008, when the National Institute of Standards and Technology issued the final portion of a $16 million study investigating the cause of the collapse of the Twin Towers and a third World Trade Center skyscraper that was not hit by a plane.

Facts alone are insufficient to destroy a conspiracy theory, of course, and in many ways a theory’s appeal has more to do with the receptiveness of its audience than the accuracy of its details. The popularity of the 9/11 conspiracy theory would continue to ebb and flow after each of these reports. But their responses to these challenges show how followers of the 9/11 conspiracy theory changed their emphases and arguments—or, more often, did not—when presented with new information.

The Popular Mechanics article may never have been published were it not for a $3 million national ad campaign by an eccentric millionaire to promote a self-published book called Painful Questions. The campaign posited that the World Trade Center was brought down in a controlled demolition and that the Pentagon was never hit by a jetliner, and asked questions about whether the fires in the Twin Towers were sufficiently hot to bring about their collapse or whether the hole in the Pentagon was big enough to fit a commercial airplane. When Popular Mechanics Editor James Meigs saw the ad, he says, “I thought, well, we’re Popular Mechanics and we’ve been reporting about what happens when planes crash, how skyscrapers are built, for 100 years. Let’s actually answer the questions.”

So the magazine went about reporting out some of the most interesting and serious conspiracy theories, and responding to them based on interviews with more than 70 experts in aviation, engineering and the military. Its article found that all of the supposedly scientific evidence for government involvement in 9/11 was based on shoddy research and, to a large extent, manipulated and misleading argumentation. The piece remains the most widely read story the magazine has ever published, with more than 7.5 million page views.

“We were the first people to actually take the conspiracy theory claims seriously and address them very directly,” Meigs says. “And the reaction was so overwhelmingly hostile, and kind of scary, that it was a real education in how these groups work and think.” Among the responses was a report by anti-Zionist conspiracist Christopher Bollyn, who claimed to have discovered why the 100-year-old engineering magazine would take part in a government cover-up of the crime of the century: A young researcher on the magazine’s staff named Benjamin Chertoff was a cousin of then-Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, and the magazine was seeking to whitewash the criminal conspiracy with its coverage.

Never mind that Chertoff had not been in his position when the story was being written, and Benjamin Chertoff had never met the man who he said might be a distant cousin. The mere mention of the connection was sufficient for conspiracists to dismiss the report.

“That was interesting. A little bit scary I think for Ben, but also kind of comical,” Meigs said. “Imagine the scenario. Let’s say somebody at Slate is related to Dick Cheney and all of a sudden he said, ‘Hey guys, I need everybody to work with me on this: We’re going to all get together to cover up the biggest mass murder in American history. Are you with me?’ “

The Popular Mechanics article was turned into a book called Debunking 9/11 Myths, which came to include interviews with more than 300 sources and eyewitnesses. David Ray Griffin responded with his own book, Debunking 9/11 Debunking in 2007, in which he reiterated theories that he said had not been adequately debunked, claimed that the only successful debunking Popular Mechanics had done was of straw men, and repeated the Chertoff cover-up accusation.

It’s worth lingering over Griffin’s response to illustrate a typical reaction among conspiracy theorists to refutation. One of the bedrocks of the conspiracy theory is that U.S. military planes should have been easily able to intercept any of the four hijacked airplanes on 9/11 to prevent the attack. The Popular Mechanics article notes that only one NORAD interception of a civilian airplane over North America had occurred in the decade before 9/11, of golfer Payne Stewart’s Learjet, and that it took one hour and 19 minutes to intercept before it ultimately crashed. Based on initial reports that misread the official crash report, conspiracists had previously cited the Stewart case as evidence that it normally only took NORAD 19 minutes to intercept civilian aircraft.

“That’s a very debated thing,” Griffin told me. “It looks like somebody has kind of changed the story there. I don’t know what happened, but I’ve read enough about it to look like that’s not true that it took that long.” And what about other physical evidence that debunks the interception theory, specifically the NORAD tapes, which document the chaos and confusion of American air defenses that morning in painstaking detail? Griffin’s response is that the tapes have likely been doctored using morphing technology to fake the voices of the government officials and depict phony chaos according to a government-written script. It’s not surprising, he says, that after 9/11, mainstream historical accounts would be revised to fit the official narrative.

“This is a self-confirming hypothesis for the people who hold it,” Meigs says. “In that sense it is immune from any kind of refutation and it is very similar to, if you’ve ever known a really hardcore, doctrinaire Marxist or a hardcore fundamentalist creationist. They have sort of a divine answer to every argument you might make.”

Another article of faith among conspiracy theorists is that the conspiracy would not have to have been very large. In Crossing the Rubicon, Michael Ruppert writes that there didn’t have to be any more than two dozen people with complete foreknowledge of the attacks to orchestrate 9/11, and that they would all be “bound to silence by Draconian secrecy oaths.” But those numbers begin to balloon out of control if all of the people and institutions accused of playing a part in the cover-up are counted. They would have to have included the CIA; the Justice Department; the FAA; NORAD; American and United Airlines; FEMA; Popular Mechanics and other media outlets; state and local law enforcement agencies in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York; the National Institute of Standards and Technology; and, finally and perhaps most prominently, the 9/11 Commission.

A Slate Plus Special Feature:

Slate’s Political Gabfest reflects on the attack and how it’s affected their lives. Listen to this special Slate Plus bonus segment by — your first two weeks are free.

Of the alleged conspirators in the cover-up, few play a greater role than Philip Zelikow, the 9/11 Commission’s executive director. A career academic and diplomat, he was asked to resign from his post in 2004 by representatives of 9/11 families because of an alleged conflict of interest stemming from his role on George W. Bush’s transition team. Zelikow recused himself from any part of the investigation dealing with the time period that he worked with the transition team, but his presence on the commission is all the conspiracists needed to discredit the entire report.

“I play a very prominent part in their demonology of the world, but the people themselves don’t come across like raving lunatics,” Zelikow says. “They’re often people who in many respects seem quite sincere, very concerned, very patient. They just are fixated.” The obsessive nature of conspiracism makes it very difficult to discuss or debate issues with some of the more hardcore believers. “They’re not really able to listen to you,” Zelikow says. “It’s almost like you’ll say something and then the tape will just replay its loop again.”

In 2007 a conspiracist confronted Zelikow in public with the “fact” that many of the hijackers are still alive. Zelikow responded that the 9/11 Commission had looked into the claims and found nothing to them but could not fit every single debunked conspiracy theory into the final version of the report. The questioner’s reply was to repeat his accusation. I had a similar experience on the same topic when questioning Griffin, who begins his book The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortionswith the “hijackers are still alive” theory. I sent him an email pointing out that this theory relied on discredited media reports—the “hijackers” they had found were just people with the same names as the hijackers. In response, he emailed me a chapter on the topic from one of his books and said he was too busy to discuss the issue further.

Another common conspiracist tactic is to obsess over minor points of contention and exaggerate the importance of often easily explained inconsistencies in very hard evidence, such as phone calls victims made to family members on the ground describing the hijackings. For example, Griffin says that the phone calls, records of which were made public as part of the 9/11 Commission, were faked by “voice-morphing” technology that fooled family members on the ground.

All the same, some conspiracy theorists have actually retreated from their more difficult-to-prove claims, such as the argument that no commercial plane hit the Pentagon. “They are focusing most of their attention on the World Trade Center stuff, where they’re clinging to a few of these now pretty well-rebutted engineering hypotheses,” Zelikow says. The most successful purveyor of these hypotheses is Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth founder Richard Gage. In March 2006 Gage heard Griffin argue on the radio that quotes from firemen provided evidence of controlled explosions in the World Trade Center. Gage was floored. “I couldn’t even get back to the office, I had to pull the car over,” he says. Gage tried to attend a Griffin lecture in Oakland the very next day, but the 600-person hall was full and he had to settle for listening to a live webstream. Within a couple of weeks he had created a PowerPoint presentation about this theory and started proselytizing to co-workers.

Two months later he started Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth, and soon after that he became a full-time activist, spreading his message that the World Trade Center investigation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology was a fraud and that there needed to be an “independent” investigation. The petition he started at the time now has signatures from more than 1,500 licensed or degreed architects and engineers, and he is considered one of the movement’s most persuasive leaders. Like Griffin, Gage argues that the three-year-long, $16 million NIST investigation, the work of nearly 100 NIST investigators, staff, and independent experts and consultants, was part of the criminal cover-up. “We’re calling for a federal grand jury investigation of the lead investigator and his co-project leader,” Gage says. “Whoever’s names are on those reports need to be investigated.”

Dozens of peer-reviewed papers have been written that support the official hypotheses, but those are dismissed as well. Both Gage and Griffin do, however, point to the movement’s own peer-reviewed paper, published by former BYU professor Steven Jones and Danish scientist Niels Harrit. Because traditional controlled demolitions would have been audible throughout lower Manhattan had they actually occurred on 9/11, conspiracists have been forced to posit a very obscure scientific explanation for their central thesis: that the demolitions used an incendiary chemical called nano-thermite. Jones and Harrit argued in their paper that they found traces of a thermitic reaction in particles of dust found at the World Trade Center.

Griffin and Gage hold this up as mainstream validation of the movement’s work, but the peer-review process of the paper is suspect. (The editor of the journal resigned over the paper after it was published without her approval, for example, and one of the paper’s peer reviewers is a 9/11 conspiracist who has speculated that the passengers on the four flights are actually still alive and living off of Swiss bank accounts.) “Since they can’t attack the science, they attack the peer-review process,” Gage responds. “Let’s have them attack the science.” The science has been addressed by Popular Mechanics and others.

At a certain point, though, debating science and theory and ideas is an exercise in futility, because the hypotheses of conspiracy theorists are not grounded in any kind of a larger understanding of the real world. “This sounds really mean,” says Erik Sofge, a reporter on the original Popular Mechanics piece and an occasional contributor to Slate. “But really, it’s like arguing over the marching speed of hobbits.”