As election fraud narratives persist, misinformation research shows sources of ‘toxic feedback loops’

The 2020 U.S.presidential election is almost a year past, but the unfounded allegations that President Biden did not win the vote persist: more than one-third of Americans think Donald Trump won. That’s despite the fact that investigations and lawsuits from around the country asserting election fraud have all failed. And the narratives pushing the disinformation are sure to continue into 2022 elections and beyond.

So how in the heck did we end up here? The University of Washington’s Kate Starbird has some answers.

Starbird, who is the faculty director of the UW’s Center for an Informed Public (CIP), took the stage Tuesday at the GeekWire Summit in Seattle to share some research into what she called “participatory disinformation.”

After culling through months of posts on Twitter, Starbird and colleagues found that while big name allies of then-President Trump were spreading erroneous messages about the election, included in the flow were tweets from ordinary citizens that were picked up and amplified.

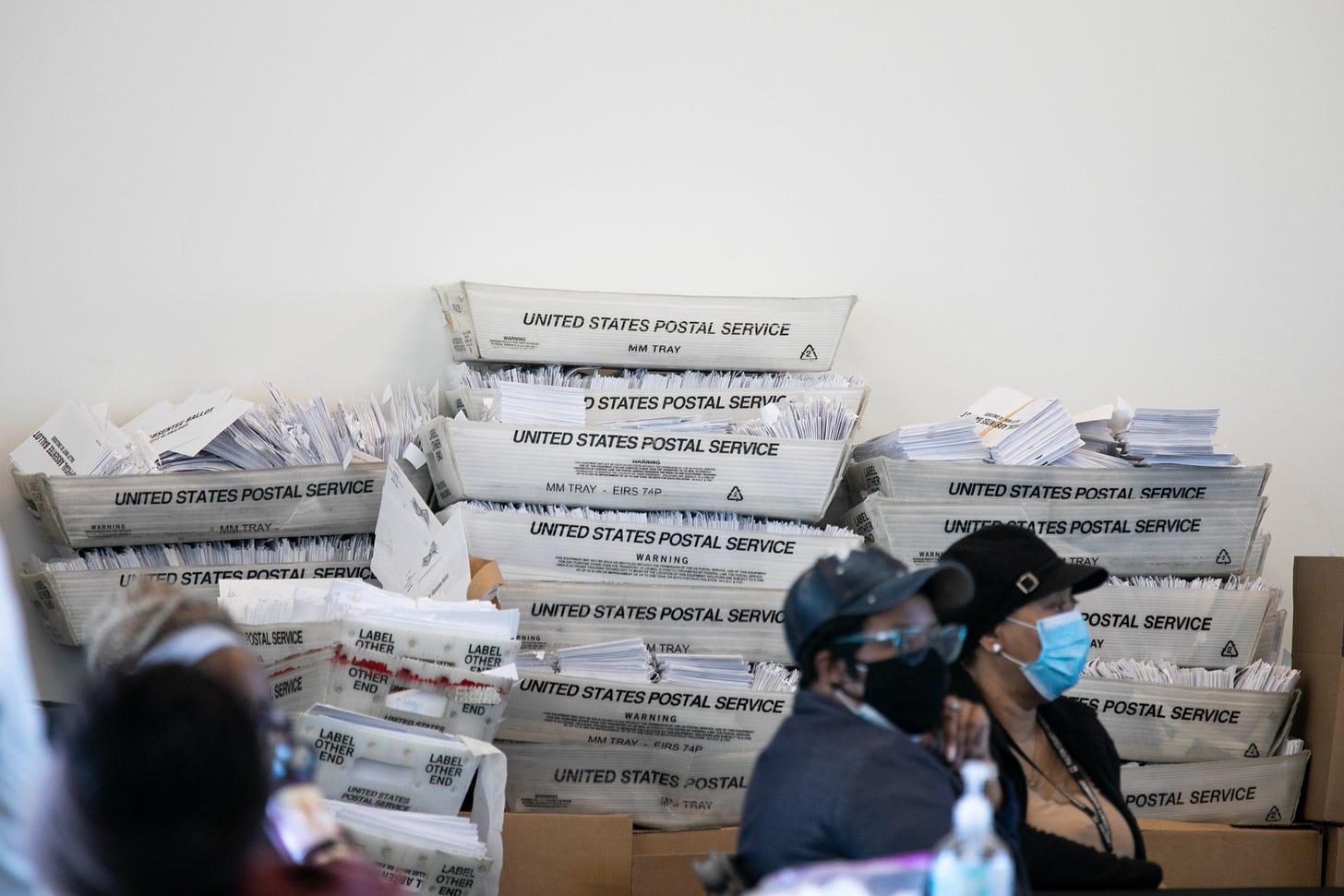

The narrative started with prominent voices — including Trump himself, his sons, conservative media members, right-wing celebrities, QAnon supporters and others — laying a foundation for misinformation and more malicious disinformation. Starbird shared a June 22, 2020 tweet from Trump that claimed without evidence that foreign governments could submit mail-in ballots against him. With this tweet and others, Trump and his allies continued reinforcing “the narrative of a rigged election,” Starbird said.

As a result, some conservative voters began seeing fraud where it didn’t exist. They shared misinformation about ballots being tossed in GOP-leaning precincts that were filled out with Sharpie pens — leading to SharpieGate — and misread official information about ballots being illegally rejected when they were not.

These inaccurate allegations were retweeted until they reached Twitter users with megaphone-sized followings, who greatly amplified the lies.

The movement coalesced under the Stop the Steal slogan and its patriot-hued calls to action that featured eagles and American flags. Trump supporters generated what Starbird called “toxic feedback loops” that kept recycling the voting fraud disinformation and fomenting anger.

“I used to think of these accounts — this was naive of me — as caricatures of political partisans. And yet, on January 6, we saw them come alive in this physical and violent protest on the capital,” Starbird said.

That was the date that Congress certified Joe Biden’s win of the presidential race, a key step in the peaceful transfer of power that some opponents had hoped to derail. Five people died in relation to the riots, which also caused $1.5 million of damage to the U.S. Capitol.

Starbird was one of many researchers who studied the role of social media in real time, throughout last year’s election as part of the Election Integrity Partnership. The coalition included the UW, Stanford University, the Digital Forensic Research Lab, and Graphika.

Last week, the right-wing activist group Project Veritas filed a defamation lawsuit against the UW and Stanford over a blog post from the partnership alleging that Project Veritas had promoted election disinformation. In response, the UW said the claims are without merit and that it is prepared to make that case in court.

Starbird is looking past the 2020 vote and considering the big picture. She wants to know how to throw a wrench in the machinery that generates the narratives of disinformation that incite violence and threaten democracy. Starbird suggested that government regulation of social media and programs providing civic media literacy are some of the answers.

“How do we stop this?” she asked. “How do we pull back from this precipice and come back to some way of having conversations based on reality and work through hard problems together?”