The roots of denialism: How the birth of smog in 1943 led to Trump and QAnon

I. The opening battle

In business schools, there’s a little parable that gets spun about the indomitable genius of American scientists and … car tires.

Right after America surrendered the Philippines in 1942, the victorious Japanese halted exports of natural rubber to the United States. No rubber from the Filipino Pará tree meant a shortage of tires for cars, jeeps, aircraft — anything that rolled. Almost overnight, the wheels of the US war machine, just gearing up to stop fascism, were coming off. But American engineers swiftly rose to the challenge — inventing the process to make synthetic rubber. With that triumph of practical ingenuity, America was back in the fight.

That’s the end of one story, but the beginning of another. What happened next does much to explain how our long-shared faith in science, and the Enlightenment ideal of empiricism that has guided American politics and business from the country’s founding, has devolved into the epistemological crisis in which we currently find ourselves. It begins in one of those brand-new rubber factories, and it involves one of the earliest experiments in what we now call fake news — a beta test of a society ruled by “alternative facts,” where there’s no longer a consensus on just about anything formerly known as the truth.

On July 26, 1943, on Aliso Street in downtown Los Angeles, a plant was busy producing butadiene, a chemical necessary to make artificial rubber, when people noticed an orange-brown cloud overhead, a hazy fog that some described initially as kind of pretty, even though it stank like hell and made your eyes water. People in nearby office buildings coughed so hard they were sent home. Historians of modern pollution call this the birth of modern smog.

Over the next few years, smog was obviously coming from sources far beyond Aliso Street and began to blanket the entire city. On still mornings, the haze thickened, and a panic settled in. “Smog interferes with thought processes,” a local doctor informed the county supervisors, “inducing fear, anxiety, and general ‘mental tailspin,’ including ‘globus hystericus,’ an imaginary lump in the throat which provokes continuous swallowing.” Local spinach crops turned silver. Then black. Then dead. The reek was so bad that Hollywood stopped shooting outdoors. Classified ads for fancy houses and apartments boasted: “Above smog.”

Officials tried everything. Emissions at coal-burning plants were capped. Backyard incinerators were banned. Housewives were urged not to shake dust mops or beat rugs. Proposals called on the city to deploy a fleet of helicopters to fan the smog away, or to bore holes through the mountains so the smog could find its way to the desert.

But the smog persisted. So the politicians finally decided to do what you did back in those days: ask scientists to use empirical data to determine the truth, the actual cause, so engineers could figure out a fix.

A Dutch immigrant named Arie Haagen-Smit jumped in to help. A pioneer in a unique branch of botanical science, Haagen-Smit had created a system that could boil down a plant and extract its essence. He could identify the plant’s defining molecule. True, the system was bulky. To crack the atomic code of “pineapple,” he had to import 6,000 pounds of them from Hawaii, chop them up, and run the juice through his series of distillation traps. But it was definitive. He’d done it with wine and onions and marijuana, too. So when he piped Los Angeles’ rusty air through his traps, according to the Science History Institute, out “dripped several ounces of a ‘vile-smelling’ brown sludge — eau de smog.”

It didn’t take Haagen-Smit long to solve the mystery. Smog was what happened when hydrocarbons, created mostly by refineries and cars, were released into LA’s famously bright sunshine. The light prompted a chemical reaction, oxidizing the molecules into smog. Haagen-Smit’s findings “assume great importance,” the Associated Press reported in 1952, “because they have been accepted as fact — and a basis for action — by the county’s air pollution control district.”

In the coming years, armed with this knowledge of smog, engineers figured out some really impressive fixes, all of them still with us — catalytic converters that neutralize pollutants before they are released into the atmosphere, gas tanks that capture escaping vapor, floating lids on refinery tanks to prevent evaporation.

Just as World War II was the birth of smog, smog was the birth of what we now call denialism.

If that were the entire story, the defeat of smog would just be another business-school parable of American know-how, like Benjamin Franklin’s kite, or Thomas Edison’s light bulb, or synthetic rubber. It’s how we like to tell the tale of American greatness: the vigorous testing of ideas leads to new truths, which turn into smart action. Thomas Jefferson set the tone in the Declaration of Independence. After charging the king with tyranny, he wrote: “To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.” Then he outlined the problem, point by point, and proposed a solution. The Declaration is a call to rebellion. But it is also a scientific proof heralding a new kind of enlightened government, the elevation of empirical thinking to the grubby realm of politics.

Which is why what actually happened right after Haagen-Smit released his findings marked a kind of turning point in American history. At the time, factories were springing up all over Los Angeles, and car sales were booming. Fixing the problem of smog would be costly, and would hinder the unfettered expansion of pollution-producing industries. So the American Petroleum Institute pioneered a response that is commonplace today. It signed up a front group with a stately name — the Stanford Research Institute — and set out to trash the research that was threatening its bottom line. It was the beginning of a 70-year-long attack on the very nature of science itself. The path of that attack has been long and winding — marked by signposts of cunning, deception, diabolical genius even — but it has led directly to the world we live in today, with daily geysers of incoherence, slurries of lies, and discharges of digital sludge. Just as World War II was the birth of smog, smog was the birth of what we now call denialism.

The Stanford Research Institute was a Potemkin think tank, funded by the very industry it was purporting to study. But as one of the first of its kind, it hadn’t yet learned how to conceal its true agenda. An oil-company executive sat on SRI’s board of directors. It was funded by the petroleum industry’s “Smoke and Fumes Committee.” And the first sentence of its mission statement declared: “The prime responsibility of the Stanford Research Institute is to serve Industry.”

No self-respecting fake institute today would make such naive mistakes. Nor would it be so foolish as to hire a respected scientist to take down another respected scientist. But that’s how SRI started. It paid Harold Johnston, an atmospheric scientist who later garnered acclaim for his work on the ozone layer, to shoot down Haagen-Smit’s findings. Instead, Johnston replicated Haagen-Smit’s work and declared him a genius for figuring out the true cause of smog. Johnston was fired.

SRI pressed on with its alternative science. It announced that its own research showed the causes of smog “have not been positively identified.” Its research supervisor, Vance Jenkins — who was also the head of the Smoke and Fumes Committee — launched a public campaign to disparage Haagen-Smit. The idea that air pollution caused smog, he declared, was nothing but an “unproved speculation” — an “interesting guess” that was being used by some “as a means of gaining favorable publicity.”

In an oral history, Haagen-Smit’s widow, Maria, remembered that these insults changed the career trajectory of her husband, whom she affectionately called Haagy. One evening, the couple attended a public talk sponsored by SRI. At the event, a scientist — bought and paid for by SRI — attacked Haagan-Smit by name. “He expressed regret that a respected scientist such as Dr. Haagen-Smit could make such a serious mistake,” Maria recalled. “I could almost feel Haagy’s blood pressure rise. He was furious. The validity of his work was being questioned! ‘I’ll show them who’s right and who’s wrong,’ he muttered as we left the room.

Haagen-Smit devoted the rest of his life to studying air pollution. He stood his ground, eventually won the argument, and became famous. He was widely known as Dr. Haagen-Smog. In 1968, Gov. Ronald Reagan appointed him to head the new California Air Resources Board. In those days, scientists who were devoted to the truth were honored, regardless of political affiliation. In the very first battle in the War on Truth, it seemed as though the truth had won. Just before Haagen-Smit died, he had one of the world’s premier environmental-research facilities named for him. It’s still there, just off I-10 in Los Angeles, the Haagen-Smit Laboratory, a monument to empirical science.

But it turned out to be a museum.

II. ‘Doubt is our product’

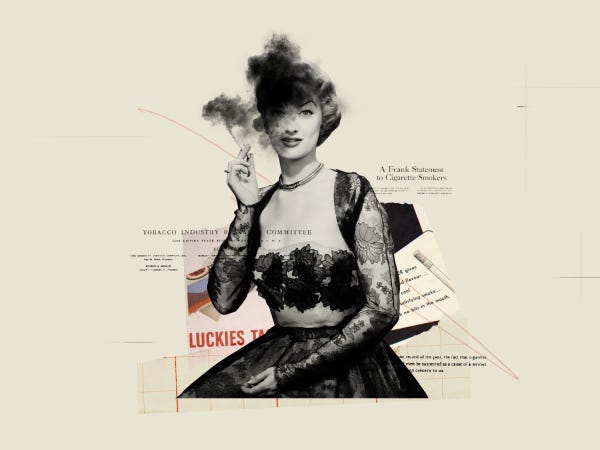

In 1952, the same year Haagen-Smit published one of his key papers on smog, the British Medical Journal published a very different paper. There was, the journal announced, a “real association between carcinoma of the lung and smoking.” Further experiments and studies confirmed the link between cancer and cigarettes. Thanks to the smog industry’s failed insurrection against scientific knowledge, the tobacco industry had a blueprint to improve upon. Like SRI, it would create a fake think tank — called, simply, the Tobacco Institute. But this time, it adopted a new strategy for denialism in the face of product-damaging science. It decided not to engage the science or the scientist at all. The tobacco industry had a new understanding: This wasn’t a question of truth. This was a publicity problem.

So the industry hired a public-relations firm, Hill & Knowlton, to deal with this disturbing new fact — that smoking is really, really bad for you. In response to the information in a tiny science paper from England, Big Tobacco took out full-page ads in American newspapers, reaching 43 million people. The ad was titled “Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers.” It said there were “many possible causes of lung cancer” and there was “no agreement” among the scientists and “no proof” tobacco was the culprit. The cause of all these cancers among smokers could be … well, anything.

The argument was simple. The science isn’t perfect, so we need more studies.

What’s striking about tobacco’s pushback to the direct, proven link between cigarettes and cancer is that it never blinked. The industry held to its proposition — that science hadn’t proved its case — for the next half a century. The “repeated assertion without conclusive proof that cigarettes cause disease,” the cigarette giant Brown and Williamson declared in 1971, “constitutes a disservice to the public.”

The point was to create, in the minds of smokers, enough doubt in the rock-solid scientific truth that they would keep on smoking. In 1969, an internal Brown and Williamson memo summed up the intent of the industry’s anti-science stance. “Doubt is our product,” the memo explained, “since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public.”

The industry’s effort to generate a permanent state of ignorance in millions of people proved so successful that Robert Proctor, a professor at Stanford University who studies the history of science, created an academic subspecialty to scrutinize this new field. He coined his own term for it: agnotology — “the study of willful acts to spread confusion and deceit, usually to sell a product or win favor.”

Occasionally, some tobacco executive would slip up and let their craven ugliness show. Like the R.J. Reynolds executive who confided in an actor on the set of a TV commercial: “We don’t smoke that shit. We just sell it. We just reserve the right to smoke for the young, the poor, the Black, and the stupid.” Or the moment in 1971 when Joseph Cullman, CEO of Philip Morris, defended tobacco’s shrivelling effect on fetuses. “Some women would prefer smaller babies,” he said.

But mostly the industry stayed on message. As long as there was a margin of a sliver of a fraction of a percent of uncertainty in the scientific studies, then the truth could not be declared the truth. As late as 1998, the chairman of Philip Morris — a man named Geoffrey Bible — said under oath and without spontaneously combusting, “I’m unclear in my own mind whether anyone dies of cigarette-smoking-related diseases.”

As it happens, 1998 was a key year in tobacco history. Nearly every state attorney general in America sued Big Tobacco for the massive tax burden created by caring for the industry’s dying customers. The attorneys general won a historic $206 billion settlement. After that, the industry gave up on Hill & Knowlton’s talking points, mostly because the US market had become so negligible. There were now more smokers in China alone — 300 million — than there were people in the United States. That’s where the action was. “Thinking about Chinese smoking statistics,” a cigarette flack named Robert Fletcher murmured out loud, “is like trying to think about the limits of space.” The industry’s denialism didn’t end when the tobacco companies lost billions of dollars in court. It just went global.

III. Discrediting science itself

In 2008, at the tail end of the George W. Bush years, an astonishing public-service announcement appeared on television. It featured former House Speaker Newt Gingrich on a sofa in front of the US Capitol, outdoors, sitting next to the serving House speaker, Nancy Pelosi. They introduced themselves and awkwardly confessed they were not friends. “But we do agree,” Gingrich said, “that our country must take action on climate change.”

As fossils buried in the YouTube strata go, this one stands out. It’s arguably the high-water mark of a bipartisan belief in the climate crisis. Today, climate denialism is so rampant that it’s difficult to think back to a time when such a complex and emerging scientific discovery — that humans are causing catastrophic levels of change in our very own ecosystem — was so widely accepted.

But thanks to the strategies developed over the years by the corporate defenders of smog and cigarettes, the fossil-fuel industry was ready. This time, though, there wasn’t a single Fossil Fuel Institute — there were lots and lots of industry-funded deniers, all with PR-ready names: the Competitive Enterprise Institute, The Heartland Institute, the George C. Marshall Institute. According to an investigation by The Guardian newspaper, more than 100 groups were set up to “deny climate science and obstruct policy solutions to global warming.” Climate denial was, in effect, its own new industry, and its sole purpose was to churn out industry-backed studies designed to look like independent research conducted by respected scientists.

The “scientists” who produced these studies were so transparently bought and paid for, they often forgot to camouflage their paymasters. One investigation revealed that the research conducted by a fellow named Willie Soon had been funded by the American Petroleum Institute, the Electric Power Research Institute, the Mobil Foundation, the Texaco Foundation, and the Charles G. Koch Foundation. There was a happy-go-lucky shamelessness to the way Soon posed as an objective scientist. Once, when he wrote an op-ed article for The Wall Street Journal, his bio said, “Mr. Soon, a natural scientist at Harvard, is an expert on mercury and public health issues.” Harvard responded by issuing a clarification that Soon had “no affiliation with Harvard University except sharing a building with Harvard students and staff on Harvard’s campus.”

Still, the industry needed something more to undermine the mounting evidence that human-caused climate change was a Fact, as Jefferson would have called it. The year after Gingrich and Pelosi sat down together on that couch, with Congress poised to enact bipartisan legislation to regulate planet-warming pollution, climate deniers made another giant advance in the mechanics of modern truth-dismantling. It was no longer enough, they realized, to try to pass off industry propaganda as objective science. Instead, the deniers set out to discredit science itself. And the weapon they used was the precise opposite of the scientific method. They created a conspiracy theory.

On November 17, 2009, three bloggers who had a penchant for bashing climate science received the first of some 6,000 emails that had been hacked from the accounts of scientists working for the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in England. What followed were a series of knee-jerk media moves that are almost invariably spurred by the words “leaked emails.” First, a few days after the leak, a blogger for The Telegraph in London slapped the suffix “gate” on the word “climate,” thus signaling a cover-up of historic proportions. A few days later, the headline on an opinion column in the paper dubbed “climategate” the WORST SCIENTIFIC SCANDAL OF OUR GENERATION. In America, the conservative talk-show host Dennis Miller invited The Telegraph’s blogger onto his show. The branding effort paid off, and soon details of the “cover-up” began to pop all over the media.

None of the details were accurate, or even close to true. But they sounded great, especially if you’re a former comedian riffing with a partisan blogger. For instance, the scandalmongers poring through the emails came across the phrase “hide the decline” and jumped to the conclusion that these scientists, acting in conspiracy, were concealing the fact that the Earth isn’t heating up, it’s actually cooling off. It was a denialism twofer: The science we’ve been fed is flat-out wrong, and the scientists themselves can’t be trusted.

In fact, if you read the full email exchange, the scientists are actually talking about something they had discussed many times before, using that very phrase. Inaccurate measurements of tree rings had previously suggested — erroneously — that the planet was actually cooling off. Now, improved temperature readings being taken all over the planet were reporting a rapid and dramatic rise — which was “hiding the decline” suggested by the tree rings. But that explanation requires reading more than three words.

In the coming years, eight different reports would exonerate the climate scientists of anything scandalous. But by then, the damage was done. The emails, which leaked just a few weeks before the Copenhagen climate conference, helped divert attention from the world’s best shot at addressing the climate crisis. But more important, they managed to replace an accepted truth with a nonexistent scandal. The bold new attack on science was a triumphant success. Today, Newt Gingrich would never sit on that sofa. In fact, he long ago apologized to the conservative base for his reckless regard for the truth. In a recent poll, only 22% of Republicans agreed with the scientific finding that humans are causing most climate change. Late last year, Donald Trump could safely say, “I’m not a believer in man-made global warming” — a claim almost as marginal as saying the Earth is flat.

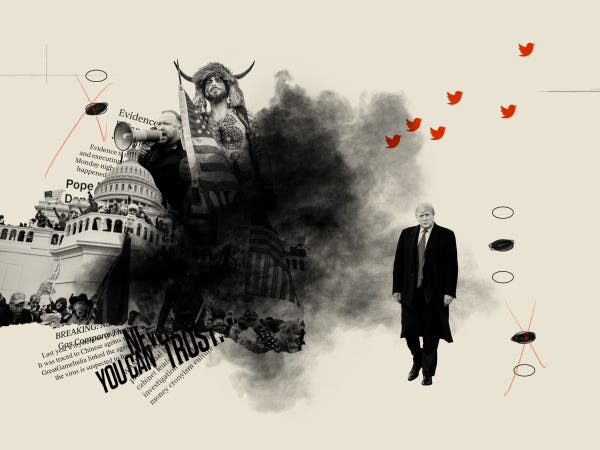

IV. The new multiverse

When Trump assumed office on January 20, 2016, the media assumed the new president would finally be forced to retire his Twitter account. There was talk of national security concerns, a sense that it was time to put away childish things. The status-keepers of Washington assumed Trump would hand off all his communications to a fully staffed press office — one of the most time-honored and visible trappings of presidential power, up there with the bulletproof limo and the Marine One helicopter on the White House lawn.

But there was no discernible pause in the presidential tweets. And no change of tone. Trump spent his first day in office claiming that attendance at his inauguration was the “the highest number in history,” when it obviously was not. The press was soon poring over side-by-side satellite photos, peering down at the vast swaths of empty space at Trump’s inauguration, compared with the jam-packed crowd at Barack Obama’s ceremony in 2008. Experts at crowd estimates were suddenly everywhere in the media. Congress actually litigated this issue before the United States Senate.

Finally, on “Meet the Press,” the presidential advisor Kellyanne Conway cleared up the confusion. As the host Chuck Todd pointed to the clear discrepancy in crowd sizes, Conway simply shrugged. The White House, she said, was relying on “alternative facts.”

“Alternative facts aren’t facts,” Todd famously replied. “They are falsehoods.” But what the press was unable to grasp at the time was that such categories no longer mattered. Under the new president, America had officially entered a new stage of denialism — one in which facts, as such, no longer exist. The wealthy have always been able to mau-mau a lie into truth, with the help of entourages of yes-men. That’s how Trump, as a petty millionaire back in the Eighties, bullied Forbes into including him in its list of top billionaires. And those of lesser means have long retreated into the gratifying fictions of conspiracy theory to slake their despair at being powerlessness in a global economy. Trump’s true achievement as president was to fuse these two forms of bonkerism, via the accelerant of social media, into a singularity of self-deception.

The Trump presidency has upended the entire Enlightenment experiment that Jefferson had outlined to a candid world. Until that moment, every aspect of modern life had been oriented around the ideal of rationality. Spy agencies, at least in theory, were supposed to supply good, solid intelligence so a president could discern the best possible course of action. Journalists were supposed to gather reliable information, albeit in a hurry, and bang out a first rough draft of what just happened. Historians, by adding more time to the process, were supposed to assemble conflicting contemporary accounts into integrated narrative truth. At the core of every major societal institution lay an assumption of empiricism. In the first century of the American republic, even organized religion served as a champion of science, which it celebrated as a means of discerning God’s divine hand in the world He created.

After the Dark Ages, trial by ordeal — when the accused were drowned or blanketed in molten lead to see whether survival revealed their innocence — had been replaced with trial by evidence, carefully weighed and set before a jury to discern the truth. But the day Trump took office, the truth became whatever he and the loudest voices on social media said it was. America was being subjected to a daily trial by ordeal.

The press harrumphed that Trump was violating democratic norms. That Trump was lying. That anyone associated with this effort should be ashamed, and that everyone else should be offended. Some tried to understand the radical new form of denialism as one of those occasional moments when a president understands how to work a new medium better than his clodhopper opponent. Kennedy and TV; Clinton and cable news; Obama and Facebook. Now, Trump and Twitter.

But those previous presidents all used their respective media to persuade voters along traditional lines. Scholars who study how we communicate are beginning to discern that social media is categorically different from past forms of media. Rather than counter an emerging truth with a new argument, or even just obfuscate as politicians had always done, this new media can be manipulated not only to shred established facts but also to throw up so many “alternative facts” that half the country is confused and the rest exhausted. What better way to deny the truth than to create your own?

Take one small example: the election rumor that Trump voters were having their votes canceled because their Sharpies bled through the ballots. One voter who used a Sharpie at the polling site in her precinct was informed by the screen on the voting machine that her ballot had been canceled. She immediately jumped on Twitter, offering absolute proof that Democrat ogres at the election board were carrying out nefarious schemes, just as everybody said.

Much later, it was cleared up. It turned out that the woman had previously requested a mail-in ballot. So when she went to vote at the polling station in person, the system actually worked perfectly. It was her mail-in ballot that was canceled. But once she made her claim on Twitter, it blew up, and a new truth was born.

Social media works less like print or broadcast and more like a reality generator. It doesn’t stand up a single alternative fact but rather spews a multiverse of truths. Some flare into existence for a few moments before being extinguished. Others spark infernos that blaze for years, consuming vast swaths of reality. Social media, as deployed by Trump and his followers, didn’t just rewrite the rulebook for denying unpleasant truths like smog and cigarettes and climate change and Joe Biden’s election. It replaced the unpleasant truths with a dizzying array of newer, more advantageous versions of reality.

V. ‘We can’t really believe our eyes’

When it comes to manipulating social media, throwing out multiple narratives is the entire point. Kate Starbird, a computer scientist at the University of Washington who studies new misinformation strategies, points to the myriad allegations of voter fraud in the 2020 election. “It was the voting machines, the mail-in voting ballot process, the Sharpies that bled through, the suitcases of votes mailed in from China,” she told me. “Some people glom onto one or another. But if you refute one, they’ll fall back onto another one because, really, they work in aggregate.” It doesn’t matter which lie you believe. The tsunami of claims on Twitter doesn’t so much create a specific truth as leave behind a residual truth of suspicion — in this case, that the election system is full of fraud and can’t be trusted.

Starbird has seen this process play out over and over again, going back to the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013. At the time, social media generated a host of conspiracy theories that the terrorism was committed by almost anyone besides the actual bombers, the Tsarnaev brothers. “First it was the Navy SEAL that did it,” Starbird recalled. “Then it was Blackwater security agents. It went on and on, for all these different suspects. At the end of the day, it wasn’t that they ever settled on one. It was that they put enough doubt out there. That people were like: ‘Oh, we can’t really believe our eyes.’”

For researchers studying the new reality generator, the key set of players are those with big followings, who transmute panicked claims into viral gold. Starbird calls them spotlighters and kingmakers. Recent studies of the exploding anti-vaccine ecosystem have shown that the overwhelming majority of the disinformation can be traced to 12 spotlighters, including Robert F. Kennedy Jr. There is lots of money to be made from this new machine. Kennedy gives highly paid speeches, while the deranged radio host Alex Jones and the adulterous TV Christian Jim Bakker have been ordered by government watchdogs to stop hawking, respectively, COVID-19-curing toothpaste and COVID-19-curing colloidal silver.

But those are the payoffs at the high end of the generator — money, fame, power. For the info-serfs feeding the bottom of the system, the reward is fellowship and community, the pleasure that comes from identifying a new bit of alternate reality and the dopamine rush of seeing it go viral. Imagine, Starbird said, that you are the lady who tweeted that evil Democrats had canceled her ballot.

“They post a tweet as just a regular person, and then they get all this attention because a minor influencer retweets them,” she said. “Then it’s retweeted over and over and over again. So all of a sudden, they get this reputational gain. The mid-range influencer, meanwhile, gets all this attention because they’re sharing stuff that’s interesting to their followers. So there are these reputational gains that happen throughout the system.”

Now imagine your tweet gets picked up by one of the top celebrity spotlighters in the political generator. Imagine the surge of powerful emotions as your new truth goes viral. And imagine how trite it would seem when a lamestream media type starts his nerdy whining about “facts,” when your 240 characters were liked by Eric Trump’s wife?

These are new truths baptized in the powerful emotions of self-discovery, internet fame, and group acceptance. They aren’t just believable — they’re actually far more credible than the antiseptic facts mustered by the amateur empiricism of daily journalism. It’s why your QAnon granddad screams at the holiday dinner table. He’s invested in the fact that Hillary Clinton drinks Adrenochrome centrifuged from the blood of infants, because he participated in some small way in the amplification of this sudden truth, while you’re left sputtering about how, well, actually, a Vox columnist did a Google analysis of search terms and she says blah blah fact blah.

Professional wrestling is pretty much everything you look for in a Trump tweet, but sweatier.

Sixty-five years ago, Roland Barthes wrote an essay comparing wrestling and boxing, which some writers have turned to in order to understand Donald Trump, who himself was one of the WWF’s most notorious barkers throughout the 1990s. The essay also goes a long way toward explaining how the two leading generators of truth work. Boxing is an organized sport that is framed, like so many modern disciplines, by the Enlightenment idea of empirical truth. Boxing matches are tests of ability, presided over by a referee whose job is to enforce a set of agreed-upon rules that will, in the end, yield a conclusive answer to a question: Who is the better fighter?

Wrestling doesn’t have any rules or referees, other than those used as mere props in what wrestling really is: a performance by the wrestlers (and the referee and barkers) to arouse powerful emotions in a brief tableaux. There are swaggering claims of triumph, absurd exaggerations, taunts, petty insults, boasts, tantrums — pretty much everything you look for in a Trump tweet, but sweatier.

Over the past few months, the new system has taken a truth that played out in real time, before the entire nation — the attempted coup d’état on January 6 — and smashed it with a folding chair until millions of Americans came to accept that what they actually saw was nothing more than a visitors’ tour of the Rotunda. It’s why Trump tried so furiously to strong-arm acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen into declaring the existence of electoral fraud in key states. Trump already had Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell and a gaggle of state legislators making the case, but they had nowhere near the juice to get the reality generator to crunch something this big. He needed a big, staggering statement of support from the most believable source possible, the United States Department of Justice. He needed fuel for the generator. “Just say the election was corrupt,” he urged Rosen, “and leave the rest to me.” Trump’s hope that the new truth engine was robust enough to flip the legitimate results of a presidential election underscores how far things have come in the few short years since he Tinkerbelled a scattering of followers into the “largest inaugural crowd in American history.”

VI. The adaptive nature of falsehood

Historians and social scientists who study falsehoods in political rhetoric note that most Americans who live outside the generator labor under the delusion that those who believe in its substitute realities are “wrong.” That they are simply ignorant, incapable of discerning fact from fiction. But numerous studies have shown that many of those who trumpet falsehoods and conspiracy theories don’t do so because they believe them. They do so because publicly repeating the falsehoods and conspiracy theories makes them feel good. They know the truth. But they get more — far more — from the lie.

The falsehoods, writes Michael Bang Petersen, a Danish scholar who studies fake news, “serve the ‘function’ of providing intangible feelings of self-esteem.” Those who join in the social-media chorus get a sense of being on the right team. And the yelps from those who are offended by their tweets only serve to reinforce the pleasure of the “in group,” creating lasting and significant bonds among its members. And the more madcap and unverifiable the false claims, the tighter the bond.

Petersen approaches the study of false rhetoric as an evolutionary biologist. He views the adaptive qualities of falsehoods not as some amateurish attempt at journalism but as something else entirely — as signal flares that enable scattered and isolated believers to form into cells of like thinkers. Analyzing bursts of fake news as an attempt to describe reality, to someone like Petersen, is like evaluating a Thanksgiving dinner from a nutritional perspective. It sort of misses that there’s this whole other point.

The history of denialism, in a sense, mirrors the process of software development. It began with its beta version as a defender of smog. Then came its release as a champion of Big Tobacco, followed by a series of upgrades — some minor, some sweeping — designed to eliminate bugs and improve performance and address the needs of specific users: climate polluters, QAnon, Donald Trump, insurrectionists. Once the province of wealthy elites, denialism now operates at scale, with every American empowered to function as their own tiny Stanford Research Institute, enshrouding the national debate in a hazy and toxic fog of misinformation and paranoia and fear.

Software, by its nature, tends to get more powerful — and more addictive — with each upgrade. The next stage in the process, according to those who have studied the new reality generator, is likely to be far more frightening than what has come before. When “falsehoods have become a routine part of the daily news diet of ordinary citizens in advanced democracies,” Petersen warns, the feedback loop moves beyond feelings of self-esteem and group bonding. The machine begins to generate something far more threatening: perpetual signaling for “pre-riot” violence. “Historically,” Petersen writes, “some of the most murderous political programs — such as the genocides of the National Socialists, the Hutu extremists in Rwanda, and the ethnic cleansings in ex-Yugoslavia — have all been explained with reference to the circulation of falsehoods by political entrepreneurs.”

There are, in fact, certain kinds of extremist rumors that often presage eruptions of ethnic violence. Among the frequent themes throughout history, Petersen cites found, are the “killing of children, poisoning of wells, and raping of women.” If those sound like antiquated bogeymen from some bygone era, consider that half of all Trump supporters now believe that top Democrats in America also run an elite pedophile ring, that vaccines are poison, and that the January 6 insurrection was a friendly tour of the Capitol that spilled out beyond the velvet rope.

We still live in a democracy, for the moment. But its operating system is no longer driven by an algorithm of truths we hold to be self-evident.