Examining the relationship between conspiracy theories and COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy: A mediating role for perceived health threats, trust, and anomie? – McCarthy – – Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy – Wiley Online Library

The COVID-19 pandemic has heralded dramatic social and economic impacts on a global scale, with social distancing measures, mask-wearing, and lockdowns the primary methods employed to date for containing the spread of the virus. At the time of writing, the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccination programs offer the hope of achieving herd immunity and a process of social and economic recovery. However, recent studies in jurisdictions with advanced vaccination roll-out programs show substantial proportions of these populations remain vaccine hesitant, creating a barrier to slowing the transmission of COVID-19 and establishing herd immunity (Cardenas, 2021; Holeva et al., 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has also led to a considerable upswing in conspiracy theory beliefs, which have been a key barrier to vaccination uptake (Miller, 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020; Van Mulukom et al., 2020). Prior theory and research suggests that conspiracy theory beliefs tend to emerge as a way to manage the negative emotions and uncertainty that arise during periods of societal disruption (Miller, 2020; van Prooijen & Douglas, 2017). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy beliefs have been linked to reduced engagement in preventative health behaviors aimed to curb COVID-19 virus spread (e.g., social distancing, good hygiene) (Bierwiaczonek et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2021; Farais & Pilati, 2021; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020). Recent research also suggests that these conspiracy theory beliefs are linked to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal (Allington et al., 2021; Bertin et al., 2020; Holeva et al., 2021; Romer & Jamieson, 2020; Salali & Uysal, 2020; Simione et al., 2021). Understanding how to reduce vaccine hesitancy is a critical public policy challenge in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic specifically (Fridman et al., 2021; Romer & Jamieson, 2020), and life-threatening viruses and diseases more broadly.

To address these challenges, our study examines the relationship between an individual’s belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories and their intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Our study builds on recent research that finds the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is mediated by the perceived health threat posed by the virus (see Romer & Jamieson, 2020). Our study extends these findings by examining additional mediational pathways—involving trust in government and anomie—that may explain the influence of specific COVID-19 conspiracy theories on COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. Trust in authorities has been found to mediate the relationship between antivaccine conspiracy theory beliefs and intentions to vaccinate against other diseases (Jolley & Douglas, 2014). Recent research also shows that mistrust in medical science and/or medical/scientific institutions mediates the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy (Allington et al., 2021; Milosevic Dordevic et al., 2021; Simione et al., 2021). Anomie, a state of mind where individuals perceive that the moral fabric of society is declining (Teymoori et al., 2016; Teymoori et al., 2017), has also been proposed as a possible mediator of this relationship but has not yet been empirically tested (Jolley & Douglas, 2014). This study is the first to examine the relevance of anomie for understanding the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19. This study also examines whether similar mediational pathways hold when examining the effect of different COVID-19 conspiracy theories on vaccine hesitancy. Our study’s findings provide insights into the potential areas of focus for ameliorating the impacts of conspiracy theories on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Conspiracy theories in the context of COVID-19

The large-scale social upheaval heralded by the COVID-19 pandemic has provided fertile ground for the growth and spread of conspiracy theories (Hartman et al., 2020; Miller, 2020). Conspiracy theories have traditionally spiked during times of societal crisis (e.g., war, terrorism, environmental disaster), when uncertainty, powerlessness, and feelings of fear and anxiety are high (Miller, 2020; van Prooijen & Douglas, 2017). In these contexts, conspiracy theories may take hold as a coping mechanism, serving an existential function by assisting individuals to make sense of a crisis through compensatory feelings of control (Douglas et al., 2017; van Prooijen & Douglas, 2017).

A range of conspiracy theories have proliferated since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hartman et al., 2020; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Van Mulukom et al., 2020), leading the World Health Organisation to declare an “infodemic” alongside the pandemic (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; WHO, 2020). For example, the belief that the expansion of the 5G mobile network facilitates COVID-19 spread emerged in the early stages of the pandemic (Ahmed et al., 2020). Since then, other conspiracy beliefs have emerged, including that COVID-19 is a hoax, that the virus is a biological weapon developed in a Chinese laboratory, and that COVID-19 vaccines are developed to harm or control the public (Miller, 2020; Van Mulukom et al., 2020). At the same time, more generalized conspiracy theories have been circulating, suggesting that the danger and scale of COVID-19 have been exaggerated by governments, media, and pharmaceutical companies for the purpose of financial gain or population control (Miller, 2020; Oleksy et al., 2021; Van Mulukom et al., 2020).

While these conspiracy theories embody very different presumptions, previous research suggests that individuals who endorse one conspiracy theory are more likely to endorse others, even when the theories are contradictory (Wood et al., 2012). Scholars have subsequently theorized that conspiracy beliefs may constitute a monological belief system, a “conspiracy mentality” comprising a persistent world view that officials (e.g., governments and other authorities) are deceptive in their explanations of world events (Imhoff & Bruder, 2014; Miller, 2020; Wood et al., 2012). Indeed, research in the COVID-19 context finds high intercorrelations between multiple, contradictory conspiracy theory beliefs (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Miller, 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020). These studies lend support to the argument that a conspiracy mentality may be a more important focus for misinformation prevention efforts, compared to tackling specific conspiracy theory beliefs (Miller, 2020). Despite these high intercorrelations, emerging research finds that different conspiracy theories may have distinct behavioral or attitudinal impacts (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Oleksy et al., 2021), suggesting there may be value in countering specific conspiracy theories, depending on the impacts of concern.

Conspiracy theory beliefs have a range of negative impacts for individuals and society including the reduction of prosocial behaviors (Jolley & Douglas, 2014; Jolley et al., 2019); trust in individuals, government or institutions (Meuer & Imhoff, 2021); normative democratic participation and political efficacy (Ardevol-Abreu et al., 2020; Imhoff et al., 2021; Jolley & Douglas, 2014); and engagement in protective health behaviors such as vaccination (Jolley & Douglas, 2014; Pummerer et al., 2021; Romer & Jameison, 2020). Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, recent research finds that the belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories is correlated with reduced intention to engage in social distancing and good hygiene behaviors, as well as reduced support for government guidelines and restrictions (Bertin et al., 2020; Bierwiaczonek et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2021; Farias & Pilati, 2021; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Marinthe et al., 2020; Pummerer et al., 2021; Romer & Jameison, 2020). Of particular relevance to the current study, recent research suggests that COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs are also associated with increased COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (Allington et al., 2021; Bertin et al., 2020; Holeva et al., 2021; Romer & Jamieson, 2020; Salali & Uysal, 2020).

Predictors of vaccine hesitancy or refusal

Attitudes toward vaccination can range from active demand to complete refusal, with vaccine hesitancy being defined as the area between these two points (Dube et al., 2013). Recent years have seen an increasing trend toward vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusal, leading to outbreaks of otherwise preventable diseases (Dube et al., 2013; Hornsey et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016). The internet has enabled vocal antivaccination activists to broadcast and diffuse their message more quickly and to larger audiences than ever before, and research finds that even short periods spent reading antivaccination websites can negatively influence vaccination intentions (Dube et al., 2013).

Several studies have examined current levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy or refusal across jurisdictions. International studies have found a greater propensity for vaccine hesitancy among individuals with lower education, lower income, and from racial or ethnic minority groups, while mixed findings on gender suggest that overall women may be more vaccine hesitant (Allington et al., 2021; Holeva et al., 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021; Robertson et al., 2021; Savoia et al., 2021; Simione et al., 2021). A number of these studies propose that a lack of trust in authorities, including scientific and medical authorities, and a lack of trust in vaccines are key mediating factors for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in these groups (Allington et al., 2021; Robertson et al., 2021; Savoia et al., 2021; Simione et al., 2021). These findings coalesce with previous research on drivers of vaccine hesitancy that finds health and vaccine risk perceptions, trust in government and health institutions, and social trust (i.e., trust in others) can influence vaccine hesitancy (Brewer et al., 2007; Dube et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016). In general, health risk perceptions are closely tied to trust in health and government institutions (Dube et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016). Individuals who have low trust in government are more likely to perceive government sources of information on vaccines as unreliable, and those who distrust health professionals are more likely to say they receive information on vaccines from antivaccination organizations (Lee et al., 2016).

Beliefs in a range of conspiracy theories have been found to influence the intention to accept vaccines for diseases (Hornsey et al., 2018; Jolley & Douglas, 2014). Jolley and Douglas (2014) found that believing in antivaccine conspiracy theories or being exposed to material supporting antivaccine conspiracy theories, reduced the intention of British parents to vaccinate their children. This effect was mediated by the perceived dangers of vaccines, distrust in authorities, and feelings of powerlessness and disillusionment. In a multinational study of vaccination attitudes, Hornsey et al. (2018) found that holding conspiracy beliefs was the strongest psychological predictor of negative attitudes toward vaccines, when other factors such as disgust reactions to blood or needles, levels of reactance (i.e., being intolerant or skeptical of consensus views), and individualistic ideological orientations were considered.

Research to date suggests that COVID-19 conspiracy theories increase individuals’ hesitancy to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (Allington et al., 2021; Bertin et al., 2020; Holeva et al., 2021; Milosevic Dordevic et al., 2021; Romer & Jamieson, 2020; Salali & Uysal, 2020; Simione et al., 2021), consistent with prior research. For example, a study in the United Kingdom and Turkey found that those who believed that the COVID-19 virus was artificially created were more likely to report vaccine hesitancy, compared to those who believed that COVID-19 had a natural origin (Salali & Uysal, 2020). Bertin et al. (2020) examined the influence of conspiracy theories on the COVID-19 vaccination intentions in France. COVID-19 conspiracy theories were classified as (a) in-group conspiracy theories (i.e., conspiracy theories that implicate malfeasance by national [French] institutions), (b) out-group conspiracy theories (i.e., conspiracy theories that implicate malfeasance by foreign actors), and (c) prochloroquine conspiracy theories that suggest that this drug is being unfairly maligned to protect government or pharmaceutical financial interests. They found that the out-group, in-group, and prochloroquine conspiracy theory beliefs, as well as a broader measure of “conspiracy mentality,” all negatively impacted COVID-19 vaccination intentions. However, the authors found that out-group conspiracy theories (i.e., those implicating foreign actors) had a stronger association with antivaccination attitudes than the in-group conspiracy theories. This suggests that different conspiracy theories can have varying effects on vaccination intentions. It also suggests a general distrust of vaccines among conspiracy theorists, as none of the conspiracy theories examined in the study related specifically to vaccines.

In a longitudinal study, Romer and Jamieson (2020) examined the influence of beliefs in three conspiracy theories on COVID-19 vaccination intentions in a national US sample across a 4-month timeframe. Beliefs in the three following conspiracy theories were averaged to create a conspiracy belief index: (a) the pharmaceutical industry created the coronavirus to increase sales of its drugs and vaccines; (b) the coronavirus was created by the Chinese government as a biological weapon; (c) some in the US Centre for Disease Control are exaggerating the danger posed by the coronavirus to damage the Trump presidency. In addition, agreement with the conspiracy theory that the vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) causes neurological disorders such as autism was considered. COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs at time 1 predicted vaccine hesitancy 4 months later, and this relationship was mediated by the perceived seriousness of the health threat to the nation posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and also by the conspiracy belief that the MMR vaccine causes autism.

These studies suggest that several factors are important for understanding the relationship between conspiracy theories and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. First, beliefs in conspiracy theories may have both unique and common effects on vaccine hesitancy (Bertin et al., 2020). Second, for those who believe in numerous conspiracy theories, as many conspiracy theorists do (Miller, 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020), a generalized distrust toward authorities may ferment. Such distrust could cause these individuals to dismiss or doubt official public health information about the risks of COVID-19 or the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines (Jolley & Douglas, 2014; Milosevic Dordevic et al., 2021). Third, COVID-19-specific conspiracy theories may influence vaccination intention by reducing the perceived health threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, and through an associated belief that vaccines can cause harm (Romer & Jamieson, 2020).

Another possible explanation for the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy is that conspiracy theories may increase perceptions of anomie (Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Jolley & Douglas, 2014; Jolley et al., 2019). Anomie has been defined as a mental state where individuals perceive that society’s social fabric is deteriorating and moral standards are eroding (Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Teymoori et al., 2016). Anomie has been found to predict conspiracy beliefs (Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999), and to be exacerbated by conspiracy theory beliefs (Jolley et al., 2019). A corollary of increased levels of anomie is that individuals may be less inclined to trust others and more inclined to engage in self-interested behavior (Jolley et al., 2019; Teymoori et al., 2016). Research suggests that social trust and associated altruistic motivations (i.e., a desire to act in the interests of others in society) are important predictors of individuals’ intentions to get vaccinated against illnesses (d’Alessandro et al., 2012; Ronnerstrand, 2013; Woelfert & Kunst, 2020). Thus, conspiracy theory beliefs may reduce intentions to be vaccinated against COVID-19 by exacerbating anomie and diminishing social trust. These relationships have been proposed (Romer & Jamieson, 2020), but have not yet been empirically examined.

The current study

The current study seeks to further explore the relationship between different COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Research to date finds that COVID-19-specific conspiracy theories are associated with increased hesitancy to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (Allington et al., 2021; Bertin et al., 2020; Holeva et al., 2021; Milosevic Dordevic et al., 2021; Romer & Jamieson, 2020; Salali & Uysal, 2020; Simione et al., 2021). The current study expands our understanding of the process by which COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs influence vaccine hesitancy. It does so by (1) exploring the potential mediating role of the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19, trust in government, and anomie and (2) examining the association between three distinct COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Three conspiracy theories were chosen to explore both the common and distinct effects of individual conspiracy theories on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Governments are using COVID-19 in a bid to permanently limit our freedoms; COVID-19 was intentionally released by China as a biological weapon; and COVID-19 vaccines will be used to harm or control society. These theories were chosen because (a) they were popularly endorsed beliefs at the time of the study and (b) they have potentially different implications for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. If a person believes that COVID-19 vaccines were designed to cause harm, they would presumably be more likely to refuse to be vaccinated. However, if someone believes that COVID-19 was a biological weapon released by China, they may view it as a harmful virus and potentially be more inclined to be vaccinated against it. It is not clear whether someone who believes that governments are exaggerating the pandemic to permanently limit individual freedoms would be willing to be vaccinated or not. While being vaccinated is a key means to eradicate COVID-19 and return life to normal, it might be seen as a form of government control and refused on that basis. Understanding the common and distinct impacts these specific conspiracy beliefs have on vaccine hesitancy has the potential to inform strategies to counter vaccine hesitancy, which is an important priority amidst the global roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines.

METHOD

This study draws on a national survey of Australians collected during the COVID-19 pandemic but shortly before Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine roll-out commenced.1 The survey assessed Australians’ attitudes toward authorities during the pandemic and included a specific focus on the influence of conspiracy beliefs on preventative health behavior and COVID-19 vaccination intentions. The survey was advertised via Facebook and hosted on the Limesurvey platform. The survey was fielded for 21 days between 22 October and 12 November 2020. A final useable sample of 779 participants was obtained, after individuals who did not complete the survey in full (N = 548) and those who did not answer a validity check correctly (N = 108) were removed from the sample. A response rate of 38.9% was calculated, when the final useable sample was considered against the initial 2004 clicks on the Facebook survey advertisement (see Murphy, Williamson et al., 2021 for further information on the survey methodology). The following section outlines the measures used in this paper. Additional items contained in the survey but not used here can be found in Murphy, Williamson et al. (2021).

The two multiitem independent variables—trust in government and anomie—were subjected to a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) (using varimax rotation) to determine the construct validity of each scale (see Table 1). Two factors with eigenvalues of >1.0 were revealed, with the trust in government items comprised a distinct factor (capturing 55.76% of the variance), and the anomie items comprised a second distinct factor (capturing 17.99% of the variance). The communalities suggested that both the trust in government and the anomie items are well represented by the factors, with no low communalities present.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Communalities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in government | |||

| I have confidence in my State/Territory Government | 0.923 | –0.249 | 0.914 |

| I trust my State/Territory Government to act in the best interests of all Australians | 0.935 | –0.220 | 0.922 |

| I generally support the decisions made by my State/Territory Government | 0.915 | –0.199 | 0.878 |

| My State/Territory Government usually acts in ways that are consistent with my own ideas about what is right and wrong | 0.922 | –0.186 | 0.884 |

| Anomie | |||

| Compared to the Australia I knew before, I barely recognise what this country is becoming | –0.428 | 0.696 | 0.668 |

| The values that made Australia great are eroding more and more with each passing year | –0.398 | 0.745 | 0.713 |

| Nowadays, ideas change so fast that it is hard to tell right from wrong | –0.082 | 0.700 | 0.496 |

| There seems to be an absence of moral standards these days | –0.146 | 0.779 | 0.629 |

| You don’t know who you can trust anymore | –0.106 | 0.723 | 0.534 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.018 | 1.619 | |

| % Variance | 55.76 | 17.99 | |

| M (SD) | 2.33 (1.39) | 3.58 (0.96) |

- These bold values indicate the loading on the selected factor.

Measures

Dependent variable

Vaccine hesitancy. The primary dependent variable in this study is vaccine hesitancy, that is, unwillingness to receive a vaccination for COVID-19. To measure vaccination hesitancy, survey respondents were asked “If a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine was developed would you voluntarily take it?” Responses were coded as yes = 0 and no = 1.

Independent variables

- Governments are using COVID-19 in a bid to permanently limit our freedoms (“government” conspiracy theory: M = 3.45; SD = 1.67).

- COVID-19 was intentionally released by China as a biological weapon (“weapon” conspiracy theory; M = 2.82; SD = 1.46).

- COVID-19 vaccines will be used to harm or control society (“vaccine” conspiracy theory; M = 2.59; SD = 1.64).

Perceived health threat. Prior research suggests that perceived risk of contracting a disease (and/or spreading it to others) influences intentions to be vaccinated (Brewer et al., 2007; Dube et al., 2013; Savoia et al., 2021). We measured the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19 using two items: “How much of a threat do you think COVID-19 poses to your personal physical health?” (M = 2.59; SD = 1.24) and “How serious a threat do you think COVID-19 poses to the health of all Australians?” (M = 2.66; SD = 1.35). Responses were measured on a 5-point (1) no threat to (5) very high threat Likert scale. As the two items were highly correlated (r(777) = .759, p < .01), and had common bivariate relationships across the other variables, a combined perceived health threat variable was formed by averaging ratings across the two items. A higher score indicates a greater perceived health threat from COVID-19 (M = 2.63; SD = 1.22).

Trust in government. Numerous studies have found that individuals who believe in conspiracy theories tend to have lower trust in government (Pummerer et al., 2021; Van Mulukom et al., 2020). This is likely to impact how information provided by the government is perceived, and during a pandemic has implications for the acceptance of government messages about risks of disease and the efficacy and safety of vaccines. In this study, trust in government is defined as the belief in the competence of state and territory governments to manage the pandemic (see Table 1 for the four items used to construct the trust scale). Each item was measured on a (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree Likert scale. A higher score on this scale indicates that participants were more trusting of the government. The sample had a mean trust in government rating of M = 2.33 (SD = 1.39; α = .96).

Anomie. Conspiracy theory beliefs have been found to exacerbate perceptions of anomie (Jolley et al., 2019), and increased levels of anomie have been proposed as a potential mediator of the relationship between conspiracy theory beliefs and vaccine hesitancy (Jolley & Douglas, 2014). Anomie was measured using five items adapted from previous work on anomie by Teymoori et al. (2016) and system identity threat by Frederico et al. (2018). These items were designed to capture the aspect of anomie reflecting the perception that society’s moral fabric is declining, including a corresponding decline in trust of others in society (see Table 1 for items). A higher score on this scale indicates that participants had higher perceived anomie (M = 3.58; SD = 0.96; α = .82).

Covariates

Several covariates were included in the analysis that have been found to be related to conspiracy theory beliefs, namely age, gender, and political ideology (Van Mulukom et al., 2020). Age was measured in years, and gender was categorized as male, female, or other. As only eight respondents indicated “other” for gender, this category was not sufficiently large to enable inclusion of a third gender category in the analysis. Gender was recoded to a two-level variable with (0) female and (1) male, with gender for the other category coded as missing.

Political ideology was measured by asking participants the following: Some people talk about left (e.g., Australian Labor Party, Greens), right (e.g., Liberal National Party; One Nation), and center to describe political parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself in terms of your support for political parties?2 Respondents were asked to indicate their political position on a scale from (1) very left-wing to (4) center to (7) very right wing. The sample included a slightly higher proportion of more right-wing leaning participants (M = 4.14; SD = 1.49).

Analytic approach

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated to explore the variables and the relationships between them (using SPSS version 26). From here, a series of path analyses were undertaken in MPLUS to examine the mediational pathways between different COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs and vaccine hesitancy. A maximum likelihood estimator was used, with vaccine hesitancy specified as a categorical variable. Hence, coefficient estimates of predictors of vaccine hesitancy represent logistic regression coefficients (unexponentiated), while the remaining estimates represent linear regression coefficients. Bootstrapping procedures using samples of 10,000 were employed to estimate the confidence intervals for all predictors in the model. An initial model was run including all three conspiracy theories as independent variables in the same model. However, a post hoc power analysis using a Monte Carlo simulation in MPLUS (Muthen & Muthen, 2002) indicated that the large, shared variance between the different conspiracy beliefs reduced the available power to detect other moderate strength mediational paths. Thus, a separate path model was run for each conspiracy theory to understand the common and unique relationships across conspiracy theory types on the mediators and on vaccine hesitancy. Post hoc power analyses of these models indicated that there was sufficient power to detect relationships of moderate strength, although the models may be less sensitive to the detection of low strength relationships. This should be born in mind when considering the significance of results for relationships with low effect sizes in these models.

RESULTS

The distribution of participants’ characteristics and the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy in the sample are displayed in Table 2. Just over half of the participants (51%) said they would not be willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, while the remaining 49% stated that they would be willing to be vaccinated.

| M | SD | Min | Max | % (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.31 | 12.46 | 18 | 83 | |

| 18–24 | 1.7 (13) | ||||

| 25–44 | 19.1 (149) | ||||

| 45–64 | 55.6 (433) | ||||

| 65+ | 23.5 (183) | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 52.4 (408) | ||||

| Male | 46.6 (363) | ||||

| Other | 1.0 (8) | ||||

| Education | |||||

| Up to secondary education or trade technical certificate | 31.1 (242) | ||||

| Tertiary education | 68.9 (537) | ||||

| Political affiliation (1 = left wing to 10 = right wing) | 4.14 | 1.49 | 1 | 7 | |

| COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy | |||||

| Not willing to take vaccine | 51.0 (397) | ||||

| Willing to take vaccine | 49.0 (382) |

Agreement with each of the three conspiracy theories is displayed in Table 3. The most popular conspiracy theory was the “government” conspiracy theory, with approximately 62% of the sample agreeing or strongly agreeing that governments are using COVID-19 in a bid to permanently limit individual freedoms. Approximately one-third (34%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed with the “weapon” conspiracy theory (34%) and with the “vaccine” conspiracy theory (35%), indicating that a third of participants thought COVID-19 had been released by China as a biological weapon, and a similar proportion believed that COVID-19 vaccines will be used to harm or control society.

| Governments are using COVID-19 in a bid to permanently limit our freedoms | COVID-19 was intentionally released by China as a biological weapon | COVID-19 vaccines will be used to harm or control society | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Government) | (Weapon) | (Vaccine) | |

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| Strongly disagree | 26.3 (205) | 30.4 (237) | 44.9 (350) |

| Disagree | 5.9 (46) | 8.7 (68) | 7.2 (56) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 5.8 (45) | 26.8 (209) | 13.0 (101) |

| Agree | 20.4 (159) | 16.7 (130) | 13.5 (105) |

| Strongly agree | 41.6 (324) | 17.3 (135) | 21.4 (167) |

Table 4 displays the bivariate correlations between all measures. There were high correlations across the three conspiracy theories. Belief in the “government” conspiracy theory correlated moderately with belief in the “weapon” conspiracy theory (r (777) = .529, p < .001) and strongly with the vaccine conspiracy theory (r(777) = .713, p < .001). Similarly, belief in the “weapon” conspiracy theory was moderately correlated with the “vaccine” conspiracy theory (r(777) = .485, p < .001). There were also some common correlates of the three distinct conspiracy theory beliefs. Those who endorsed one of the three COVID-19 conspiracy theories were more likely to be female, have a more right-wing political ideology, perceive higher anomie, have lower trust in government, and perceive a lower health threat from COVID-19. Correlates of greater vaccine hesitancy included being younger, having a more right-wing political ideology, being more likely to endorse a conspiracy theory, having higher perceptions of anomie, having lower trust in government, and perceiving a lower health threat from COVID-19.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | –.025 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Political ideology | –.070 | .235** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Government conspiracy | –.107** | .272** | .504** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Weapon conspiracy | .013 | .115** | .466** | .529** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Vaccine conspiracy | –.107** | .139** | .390** | .713** | .485** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Anomie | .033 | .153** | .485** | .618** | .542** | .527** | 1 | |||

| 8. Trust in government | .110** | –.265** | –.451** | –.712** | –.353** | –.523** | –.505** | 1 | ||

| 9. Perceived health threat | .210** | –.263** | –.490** | –.724** | –.353** | –.633** | –.461** | .602** | 1 | |

| 10. Vaccine hesitancy | –.118** | – | .378** | .614** | .381** | .752** | .450** | –.487** | –.615** | 1 |

- *p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

- Note: A correlation between gender and vaccine hesitancy was not conducted because both are dichotomous variables.

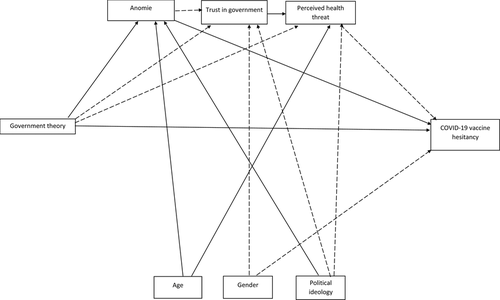

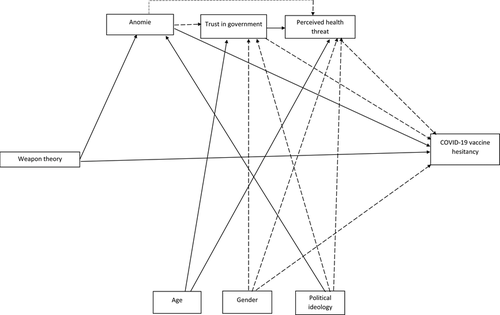

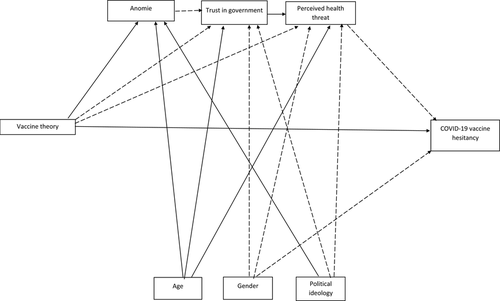

Path analysis

Figures 1–3 show the results of the three path models. The direct and indirect effects of the three models are also summarized in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. All models showed a negative, direct association between each conspiracy theory and vaccine hesitancy, but there were variations in indirect effects or mediational pathways. In addition, the coefficients suggest that the vaccine conspiracy theory had the strongest direct effect on vaccine hesitancy, while the weapon conspiracy theory had the weakest direct effect on vaccine hesitancy.

Model 1: Path model showing standardized relations between the government conspiracy theory belief, perceived health threat, trust in government, anomie, and other predictors of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. Paths shown have confidence intervals of p ± .025; unbroken lines indicate positive relationships while broken lines indicate negative relationships

Model 2: Path model showing standardized relations between the weapon conspiracy theory belief, perceived health threat, trust in government, anomie, and other predictors of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. Paths shown have confidence intervals of p ± .025; unbroken lines indicate positive relationships while broken lines indicate negative relationships

Model 3: Path model showing standardized relations between the vaccine conspiracy theory belief, perceived health threat, trust in government, anomie, and other predictors of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. Paths shown have confidence intervals of p + .025; unbroken lines indicate positive relationships while broken lines indicate negative relationships

| Standardized coefficients (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomie | Trust in government | Perceived health threat | Vaccine hesitancy | |

| Model 1: Government conspiracy theory | ||||

| Age | 0.104 (0.048, 0.161) |

0.043 (–0.005, 0.094) |

0.128 (0.081, 0.175) |

–0.012 (–0.087, 0.062) |

| Gender |

–0.083 (–0.193, 0.030) |

–0.138 (–0.241, –0.036) |

–0.094 (–0.193, 0.006) |

–0.370 (–0.524, –0.219) |

| Political ideology |

0.247 (0.187, 0.308) |

–0.088 (–0.156, –0.019) |

–0.139 (–0.201, 0.079) |

0.004 (–0.083, 0.091) |

| Government theory | 0.512 (0.451, 0.571) |

–0.588 (–0.658, –0.517) |

–0.539 (–0.629, –0.458) |

0.274 (0.150, 0.400) |

| Anomie |

–0.093 (–0.158, –0.028) |

0.010 (–0.054, 0.074) |

0.145 (0.036, 0.251) |

|

| Trust in government |

0.131 (0.058, 0.206) |

–0.061 (–0.163, 0.051) |

||

| Perceived health threat |

–0.433 (–0.539, –0.332) |

|||

| Model 2: Weapon conspiracy theory | ||||

| Age |

0.051 (–0.010, 0.112) |

0.102 (0.047, 0.161) |

0.157 (0.105, 0.208) |

–0.014 (–0.087, 0.060) |

| Gender |

0.080 (–0.038, 0.198) |

–0.306 (–0.425, –0.189) |

–0.170 (–0.284, –0.057) |

–0.320 (–0.469, –0.177) |

| Political ideology |

0.296 (0.229, 0.360) |

–0.210 (–0.284, –0.136) |

–0.193 (–0.261, –0.123) |

–0.018 (–0.107, 0.071) |

| Weapon theory |

0.394 (0.332, 0.454) |

–0.044 (–0.118, 0.031) |

–0.045 (–0.114, 0.021) |

0.131 (–0.215, –0.044) |

| Anomie |

–0.360 (–0.432, –0.287) |

–0.137 (–0.208, –0.064) |

0.165 (0.064, 0.267) |

|

| Trust in government |

0.389 (0.315, 0.462) |

0.131 (0.043, 0.216) |

||

| Perceived health threat |

–0.535 (–0.628, –0.449) |

|||

| Model 3: Vaccine conspiracy theory | ||||

| Age |

0.101 (0.044, 0.161) |

0.070 (0.015, 0.125) |

0.127 (0.076, 0.176) |

–0.007 (–0.077, 0.064) |

| Gender |

0.043 (–0.072, 0.157) |

–0.286 (–0.397, –0.173) |

–0.181 (–0.283, –0.083) |

–0.298 (–0.448, –0.146) |

| Political ideology |

0.334 (0.277, 0.388) |

–0.176 (–0.249, –0.103) |

–0.171 (–0.230, –0.111) |

0.017 (–0.062, 0.099) |

| Vaccine theory |

0.403 (0.349, 0.455) |

–0.298 (–0.361, –0.234) |

–0.385 (–0.444, –0.324) |

0.581 (0.509, 0.657) |

| Anomie |

–0.244 (–0.315, –0.173) |

–0.027 (–0.093, 0.042) |

0.020 (–0.065, 0.107) |

|

| Trust in government |

0.271 (0.200, 0.342) |

–0.068 (–0.154, 0.024) |

||

| Perceived health threat |

–0.297 (–0.393, –0.201) |

|||

- *p < .05.

- **p < .01.

- ***p < .001.

- 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals.

| Vaccination hesitancy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% Confidence intervals | |

| Model 1: Government conspiracy theory (sum of indirect effects) | 0.343 (0.049)*** | (0.248, 0.442) |

| Anomie | 0.074 (0.028)** | (0.018, 0.129) |

| Trust in government | 0.036 (0.032) | (–0.030, 0.098) |

| Perceived health threat | 0.233 (0.035)*** | (–0.169, 0.306) |

| Model 2: Weapon conspiracy theory (sum of indirect effects) | 0.095 (0.028)** | (0.040, 0.150) |

| Anomie | 0.065 (0.021)** | (0.025, 0.108) |

| Trust in government | 0.006 (0.006) | (–0.004, 0.020) |

| Perceived health threat | 0.024 (0.019) | (–0.012, 0.060) |

| Model 3: Vaccine conspiracy theory (sum of indirect effects) | 0.143 (0.024)*** | (0.097, 0.192) |

| Anomie | 0.008 (0.018) | (–0.026, 0.044) |

| Trust in government | 0.020 (0.014) | (–0.007, 0.047) |

| Perceived health threat | 0.114 (0.021)*** | (0.075, 0.157) |

- *p <.05.

- ** p < .01.

- *** p < .001.

Model 1 displays several direct and indirect effects between the government conspiracy theory and vaccine hesitancy (see Figure 1 and Tables 5 and 6). First, there was a significant direct, positive relationship between the government theory and vaccine hesitancy. Government conspiracy theory beliefs were also indirectly related to vaccine hesitancy through increased perceptions of anomie and reduced perceived health threats posed by COVID-19. In this model, belief in the government conspiracy theory was positively associated with anomie, and negatively associated with trust in government and with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. In turn, anomie was positively associated with vaccine hesitancy, and perceived health threats were negatively associated vaccine hesitancy. Anomie was negatively associated with trust in government, and trust in government was positively associated with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. Age was positively associated with anomie and the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19, while gender was negatively associated with trust in government (males were less trusting than females), and negatively associated with vaccine hesitancy. Having a right-wing political ideology was positively associated with anomie, and negatively associated with trust in government and with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19.

In Model 2, belief in the weapon conspiracy theory had a direct positive relationship with vaccination hesitancy (see Figure 2 and Table 5). There was also a significant indirect effect of the weapon conspiracy theory on vaccine hesitancy through its positive association with anomie; no other indirect effects were evident (see Table 6). In this model, greater belief in the weapon conspiracy theory was positively associated with anomie, and anomie in turn was negatively associated with trust in government and with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. There was a negative association between both trust in government and the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy, and a positive association between anomie and vaccine hesitancy. In terms of covariates, age was positively associated with trust in government and the perceived health threats posed by COVID-19. Gender was negatively associated with trust in government and with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19, and negatively associated with vaccine hesitancy. Having a right-wing political ideology was positively associated with anomie, and negatively associated with trust in government, and with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19.

In Model 3, belief in the vaccine conspiracy theory had a direct, positive effect on vaccine hesitancy. Belief in the vaccine conspiracy theory was also significantly indirectly associated with vaccine hesitancy through its negative association with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. No other indirect effects were significant. In Model 3, anomie was negatively associated with trust in government, and trust in government was positively associated with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. Age was positively associated with anomie, trust in government and the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19. Gender was negatively associated with trust in government and the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19, and was negatively associated with vaccine hesitancy. Having a more right-wing political ideology was positively associated with anomie, negatively associated with trust in government, and negatively associated with the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the influence of three distinct COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and further tested potential mediational pathways through which COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs may influence vaccine hesitancy. Our findings suggest there are both common and unique mediational pathways for different conspiracy theories on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy; however, belief in any of the conspiracy theories was directly associated with increased vaccine hesitancy. Our study also suggests that while the mediational paths vary across conspiracy theories, anomie and perceived health threat posed by COVID-19 were the most common mediational paths to vaccine hesitancy. Anomie mediated associations between belief in the weapon conspiracy theory and vaccine hesitancy, while perceptions of the health threat posed by COVID-19 mediated the relationship between belief in the vaccine conspiracy theory and vaccine hesitancy. Both anomie and perceptions of health threats mediated the relationship between the government conspiracy theory and vaccine hesitancy. These findings are consistent with recent research (i.e., Romer & Jamieson, 2020) that suggests COVID-19 conspiracy theories may influence vaccine uptake indirectly by changing perceptions of the personal health threat posed by COVID-19. However, our findings also suggest perceptions of anomie, operationalized in this study as a lack of social trust and a view that the moral order or social fabric of society is deteriorating, is another important mediational path influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. A further interesting finding from our study was that there was no effect on trust in Australian state or federal governments among those who believed in the conspiracy theory that suggests COVID-19 is a biological weapon intentionally released by China, while the two other COVID-19 conspiracy theories were negatively associated with trust in the Australian government. This suggests that the association between COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs and trust in authorities can depend on the specific out-groups that are identified as the source of the conspiracy (Bertin et al., 2020; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Oleksy et al., 2021). Specifically, conspiracy theories targeting malevolent international actors may potentially limit the effects of conspiracy theory beliefs on trust in national or state governments.

Before we discuss the implications of our findings, it is necessary to highlight the limitations of our study, which need to be considered when interpreting the findings. First, this study relies on cross-sectional survey data, and while mediation analysis can provide some insights into the process by which phenomena may be related, it does not test causality. Thus, we cannot determine the temporal and causal relationships between conspiracy theory beliefs, mediator variables, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Aligned to this, the temporal direction of the relationships between perceptions of anomie and COVID-19 conspiracy theories cannot be confirmed, and a bidirectional or reciprocal relationship between these factors is possible and warrants further research. Despite this limitation, our findings are supported by recent longitudinal assessments of the influence of conspiracy theory beliefs on vaccination intentions (see Romer & Jamieson, 2020). Second, the study is limited to individuals who were active on Facebook during the survey fielding period. As such, our study sample is not a probability sample (although the sample was found to be broadly representative of the Australian population). While a sample recruited via Facebook is a convenience sample, fielding surveys via Facebook enables timely and cost-effective capture of emerging issues—an important consideration when collecting data during the COVID-19 pandemic. We should also highlight that sampling via Facebook does address a key criticism of previous conspiracy theory studies. Prior research has been criticized because samples have not been drawn from populations with a sufficiently high prevalence of conspiracy theorists to enable in-depth exploration of the drivers of this phenomenon (Douglas & Sutton, 2018). Facebook is a key platform for the dissemination and uptake of conspiracy theories, and thus provides access to a population with a denser prevalence of conspiracy theorists (Bruns et al., 2020; Papakyriakopoulos et al., 2020). As is evidenced by the endorsement of conspiracy theory beliefs among our sample, we were able to obtain a relatively high prevalence of conspiracy theorists using this sampling method.

Returning to the implications of our findings, they suggest that targeting perceptions of anomie and the perceived health threat posed by COVID-19 are the most direct levers available for influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. At least one of the models in this study found that these two mediators were negatively associated (i.e., that anomie was associated with reduced perceived health threat posed by COVID-19). While focusing on increasing perceptions of the health threat posed by COVID-19 may bolster vaccination intentions, there is a risk that increasing fear-based public health messaging may fuel conditions of uncertainty and negative emotions that attract people to conspiracy theories as a coping mechanism (Chou & Budenz, 2020). Indeed, recent research suggests that COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs might help to diffuse death anxiety, and thus reduce the motivation to get vaccinated (Simione et al., 2021). Additionally, acceptance of information on the health threats associated with COVID-19 requires trust in those delivering this information (Dube et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016). In line with previous research (Pummerer et al., 2021; Van Mulukom et al., 2020), our findings suggest that conspiracy theorists in general have low trust in government. An alternative or complimentary focus for countering the impacts of conspiracy beliefs on vaccination uptake, therefore, could be to focus on building public trust in government. In fact, recent research suggests that governments that operate in ways that seek to build trust may be able to counter the impacts of COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs (Murphy, McCarthy et al., 2021). If government actions and decisions are perceived to be fair, effective, transparent, and commensurate with risk, they may be able to build trust with harder to reach population groups, such as those prone to believing in conspiracy theories (Murphy, McCarthy et al., 2021). This would be a valuable investment for governments during periods of significant societal disruption (such as the COVID-19 pandemic), as they continue to rely on a wellspring of public trust in order to facilitate compliance with a range of changing restrictions. Investment by governments in trust-building strategies may result in substantial social and health dividends. This has been evident in Australia, with growing levels of public trust seeming to arise from a strongly public health-led response to the pandemic (Goldfinch et al., 2021), in contrast to other jurisdictions such as the United States and United Kingdom where falling trust has been seen (Brenan, 2021; Davies et al., 2021). Alongside this, there has recently been a rapid uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations as they have become more widely available in Australia, with early signs of vaccine hesitancy rapidly diminishing.

Ameliorating the exacerbation of anomie that conspiracy theories seem to provoke could also decrease COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. While existing literature finds that perceptions of rapidly deteriorating or changing moral norms may provide fertile ground for the growth of conspiracy theory beliefs, our findings support a more limited body of research indicating that conspiracy theories can also exacerbate or contribute to anomic states (Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Jolley et al., 2019). Conspiracy theories might provide individuals with a clearer moral framework through which to understand events during periods of social upheaval; however, it does not appear that they lead to the resolution of anomic states (Van Prooijen, 2018; Van Prooijen & Jostmann, 2013). Our study focused on the social trust aspect of anomie (i.e., the perception that the social fabric and moral order is deteriorating and that others are increasingly self-interested) (Teymoori et al., 2016; Teymoori et al., 2017). When individuals feel reduced trust in the moral standards of society, they are likely to experience a contraction of the social self, to deidentify from the superordinate group, and to perceive a greater potential cost of behaving in a cooperative and mutually beneficial manner with others (Teymoori et al., 2017). These perceptions can then create the conditions for increasingly self-interested and/or antisocial behavior, and reductions in prosocial and altruistic behavior (Jolley et al., 2019; Teymoori et al., 2017). This is likely to contribute to vaccine hesitancy, with vaccine uptake previously found to be associated with altruism and social trust (d’Alessandro et al., 2012; Ronnerstrand, 2013; Woelfert & Kunst, 2020). So, how can anomie be ameliorated? The limited body of extant research suggests that increasing engagement with communities, creating a shared sense of identity, building social and economic stability, and reducing inequality could contribute to reducing perceptions of anomie at a population level (Teymoori et al., 2017). This might in turn foster prosocial behaviors such as vaccination.

While there were some diverse impacts for the distinct (and to some extent contradictory) conspiracy theory beliefs examined in this study, these beliefs had moderate relationships with each other, suggesting that at least some individuals agreed with all three. This is consistent with previous research showing that individuals can simultaneously believe in several contradictory conspiracy beliefs. Such findings suggest that these beliefs may be better understood as being a symptom of a conspiracy mentality, a mindset that distrusts powerful groups and believes that authorities are often deceptive in their explanations for major events (Miller, 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020). This creates some challenges to identifying effective and fruitful targets for intervention. That is, is it better to focus on the most prevalent or content-relevant conspiracy theories to counter specific problematic behaviors, or to focus more broadly on reducing individuals’ susceptibility to a conspiracy mindset? There is often an assumption that effectively countering a single conspiracy theory will simply lead individuals to replace it with another, which implies conspiracy-specific targeted interventions may be futile (Miller, 2020; Romer & Jamieson, 2020).

Previous research has indicated that it may be possible to act to prevent vaccine-specific conspiracy theory beliefs if counter-information is provided prior to exposure to the conspiracy theory belief. Given it is much harder to disabuse conspiracy beliefs once they are accepted, it has been suggested that prevention is better than cure (Douglas & Sutton, 2018; Jolley & Douglas, 2014; 2017). The findings of Lewandowsky et al. (2012) on countering misinformation suggest repeat and early warnings about misinformation in relevant locations (e.g., on social media sites such as Facebook), encouraging healthy skepticism about information sources, and providing evidence in a way that endorses the values of the audience, could collectively increase the receptivity, cognitive processing, and recall of anticonspiracy information. Social media may also provide an opportunity to effectively disseminate provaccine messages; research suggests that the provision of balanced information about vaccines, which acknowledges concerns and avoids jargon and is delivered by health providers, could be a promising approach for positively influencing vaccination intentions (Puri et al., 2020).

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study confirm that the recent growth in conspiracy theory beliefs, particularly those centered on potential vaccine harm, pose a substantial threat to the large-scale uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, and thus the achievement of herd immunity to COVID-19. COVID-19 conspiracy theories appear to influence vaccine hesitancy through increasing perceptions of anomie and decreasing perceptions of the health threats posed by COVID-19, though different conspiracy theories show some variation in mediational pathways. Ameliorating perceptions of anomie in order to reduce the uptake and the impacts of conspiracy theories may require broader social and political responses that create a sense of shared identity, enhance community connectedness, and increase economic and political stability. Increasing trust in government may be another fruitful focus, which could influence how trustworthy information about the health impacts of COVID-19 and vaccination are deemed. In the context of the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccination programs internationally, there is an urgent need to better understand how COVID-19 conspiracy theories can be effectively countered, as COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy will continue to have very real and avoidable effects on mortality and morbidity globally.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a Griffith Criminology Institute Strategic Grant.