Nazi Collaborator Monuments in Ukraine

This article was originally published on The Forward in January 2021.

There are hundreds of statues and monuments in the United States and around the world to people who abetted or took part in the murder of Jews and other minorities during the Holocaust. As part of an ongoing investigation, the Forward has, for the first time, documented them in this collection of articles. For an initial guide to each country’s memorials click here. For a 2022 update to the investigation, click here.

Note: beginning in 2014, when the Maidan uprising brought a new government to Ukraine, the country has been erecting monuments to Nazi collaborators and Holocaust perpetrators at an astounding pace — there’s been a new plaque or street renaming nearly every week. Because of this, the Ukraine section represents an extremely partial listing of the several hundred monuments, statues, and streets named after Nazi collaborators in Ukraine.

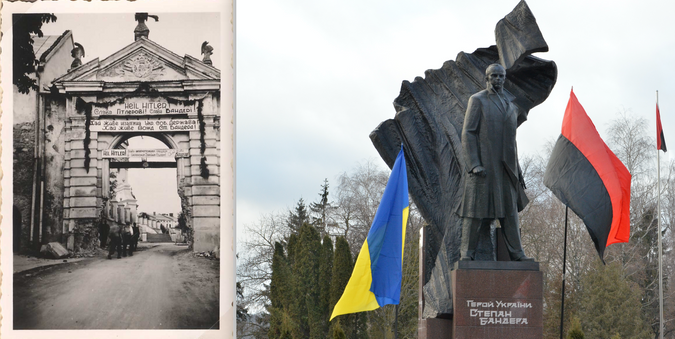

L’viv and Ivano-Frankivsk — 1.5 million Jews, a quarter of all Jews murdered in the Holocaust, came from Ukraine. Over the past six years, the country has been institutionalizing worship of the paramilitary Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which collaborated with the Nazis and aided in the slaughter of Jews, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which massacred thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles. A major figure venerated in today’s Ukraine is Stepan Bandera (1909–1959), the Nazi collaborator who led a faction of OUN (called OUN-B); above are his statues in L’viv (left) and Ivano-Frankivsk (right). Many thanks to Per Anders Rudling, Tarik Cyril Amar and Jared McBride for their guidance on Ukrainian collaborators.

Left, Nazi propaganda photo; Bandera statue in Ternopil, Ukraine. Photo by Mykola Vasylechko

Ternopil and numerous other cities — another statue of Bandera in Ternopil. Above left is a photo from Zhovkva 1941, when OUN members welcomed the Nazis, assisting with their murder of Jews. The banners include “Heil Hitler!” and “Glory to Bandera!”

Ukraine has several dozen monuments and scores of street names glorifying this Nazi collaborator, enough to require two separate Wikipedia pages. Prominent honors include a joint monument to him and Roman Shukhevych in Cherkasy, Horishniy, Pochaiv, Rudky and Zaviy; a monument to him, Shukhevych and other OUN leaders in Morshyn; a monument to him and his father in Pidpechery; a plaque and monument in Lutsk; a bas-relief, monument and museum in Dubliany; a plaque, monument and museum (with bust) in Stryi; a plaque, street and monument in Zdolbuniv; monuments in Berezhany, Boryslav, Buchach, Chervonohrad, Chortkiv, Drohobych, Dubno, Hordynya, Horodenka, Hrabivka, Kalush, Kamianka-Buzka, Kolomiya, Kozivka, Kremenets, Krushel’nytsya, Kyiv, L’viv, (and a plaque), Mlyniv,Mostyska, Mykolaiv (L’viv oblast), Mykytyntsi, Nyzhnye (Sambir raion), Pidvolochysk, Romanivka, Sambir, Skole, Sniatyn, Staryi Sambir, Seredniy Bereziv, Sokal, Sosnivka, Strusiv, Terebovlia, Truskavets, Turka, Uzyn, Velyki Mosty, Verbiv, Zahirochka and Zalishchyky; a plaque and street in Sniatyn and Zhytomyr; plaques in Ivano-Frankivsk, Khmelnytskyi and Rivne; museums in Staryi Uhryniv (with a statue and memorial plaque) and Volya-Zaderevatska (with a bust and bas-relief); a park in Kamianka-Buzka; and a school in Dobromyl.

Kyiv — In 2016, a major Kyiv boulevard was renamed after Bandera. The renaming is particularly obscene since the street leads to Babi Yar, the ravine where Nazis, aided by Ukrainian collaborators, exterminated 33,771 Jews in two days, in one of the largest single massacres of the Holocaust. Both the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the World Jewish Congress condemned the move.

Roman Shukhevych memorials in Ukraine. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Krakovets, L’viv and numerous other towns — Monuments to Roman Shukhevych (1907–1950), another OUN figure and Nazi collaborator who was a leader in Nazi Germany’s Nachtigall auxiliary battalion, which later became the 201st Schutzmannschaft auxiliary police unit. Shukhevych later commanded the brutal Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), responsible for butchering thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles.

The monument in Krakovets (above left) and plaque in L’viv (above right) are two of many Shukhevych statues in Ukraine. This includes joint monuments to him and other nationalists in several cities (see Bandera entry above) a monument to him and other nationalists in Sprynya; a monument, two plaques and a bas-relief in L’viv Polytechnic National University in L’viv; and monuments in Ivano-Frankivsk, Kalush, Khmelnytskyi, Khust, Kniahynychi, (and a plaque), Kolochava, Oglyadiv,Shman’kivtski, Staryi Uhryniv(at the Stepan Bandera museum), Tyshkivtsyah, Tyudiv, and Zabolotivka; plaques in Buchach, Kamianka-Buzka,Kolomyia, Pukiv, Radomyshl’, Rivne and Volya-Zaderevatska; a museum in Hrimne; a stadium in Ternopil; and a school in Ivano-Frankivsk. The Algemeiner on Israel slamming naming the Ternopil stadium for Shukhevych.

Even more shocking are the Shukhevych monuments in Canada and the U.S.

Additionally, Shukhevych is honored with several dozen streets in Ukraine. Most of the Bandera and Shukhevych statues are in western Ukraine, in towns where the Jewish population was exterminated by paramilitaries loyal to these men. A major boulevard has been named for Shukhevych in Kyiv as well. The World Jewish Congress condemned the glorification of Shukhevych and the statue in Ivano-Frankivsk.

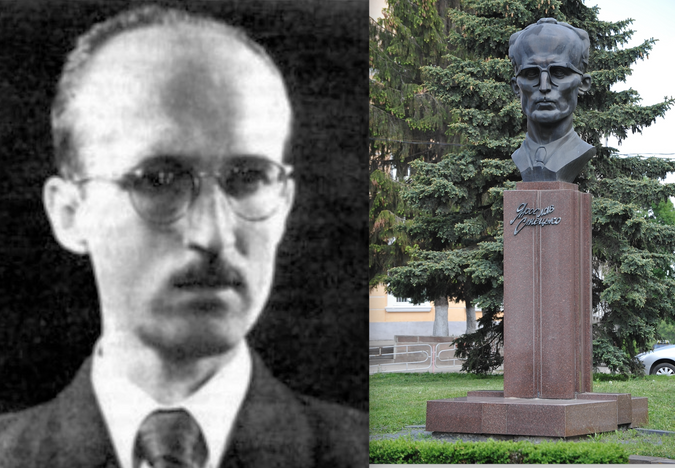

Yaroslav Stetsko, Stetsko bust in Ukraine. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Ternopil — A bust of the genocidal Yaroslav Stetsko (1912–1986), who led Ukraine’s 1941 Nazi-collaborationist government which welcomed the Germans and declared allegiance to Hitler. A rabid antisemite, Stetsko had written “I insist on the extermination of the Jews and the need to adapt German methods of exterminating Jews in Ukraine.” Five days prior to the Nazi invasion, Stetsko assured OUN-B leader Stepan Bandera: “We will organize a Ukrainian militia that will help us to remove the Jews.”

He kept his word — the German invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by horrific pogroms with the incitement and eager participation of OUN nationalists. The initial L’viv pogrom alone had 4,000 victims. By the war’s end, Ukrainian nationalist groups massacred tens of thousands of Jews, both in cooperation with Nazi death squads and on their own volition.

Stetsko memorials in Ukraine

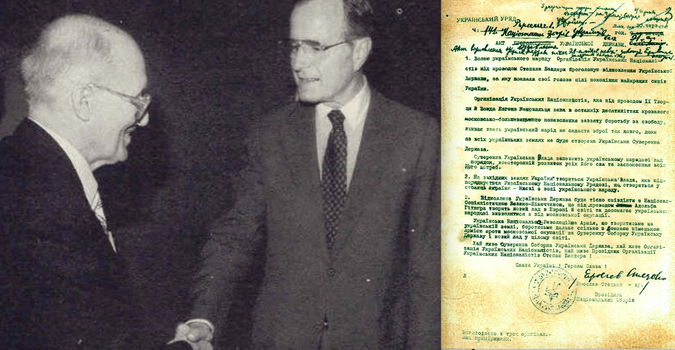

Stryi and thirteen other locations — Additional Stetsko monuments are found in Stryi (above left), which also has a Stetsko street, Velykyi Hlybochok (above right), which also has a Stetsko museum (with plaque) and school, Kam’yanky and Volya Zaderevatska. Stetsko also has a joint monument to him and other OUN leaders in Morshyn and streets in Dubno, Khmelnytskyi, Lutsk, L’viv, Monastyrys’ka, Rivne, Rudne, Sambir and Ternopil. After the war, Stetsko — the man who formally pledged his government’s loyalty to Hitler — moved to the U.S., where he quickly rose into the highest circles of Washington. He was lauded as leader of freedom fighters by Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Below left, Stetsko meeting with then-Vice President Bush, 1983. Below right, Stetsko’s signature on the Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood with a pledge to “work closely with National-Socialist Greater Germany under the leadership of Adolf Hitler.”

Stetsko with George H.W. Bush; Stetsko’s signature. By Wikimedia Commons

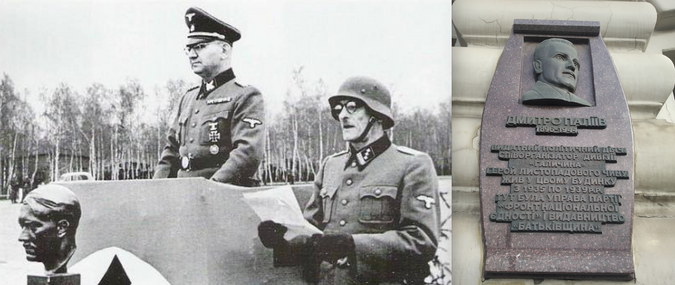

Dmytro Paliiv; Paliiv plaque in Ukraine. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

L’viv — A memorial plaque to Dmytro Paliiv (1896–1944), co-founder and SS-Hauptsturmführer of the SS Galichina 14th Division of the Waffen-SS (1st Ukrainian), unveiled 2007. SS Galichina was formed as a division in the Waffen-SS in 1943; among the formation’s war crimes is the Huta Pieniacka massacre, when an SS Galichina subunit slaughtered 500–1,200 Polish villagers, including burning people alive.

Above left, Paliiv (holding paper) at an SS ceremony, 1943–1944. This Waffen-SS officer has a plaque and bas-relief in his birthplace of Perevozets’ (unveiled 2001) as well as a plaque and street in Kalush. The JTA reported on death threats to a man who opposed naming the street.

Below left, a march in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), western Ukraine, 1941; below right, march celebrating the 71st anniversary of SS Galichina’s founding, L’viv, western Ukraine, 2014. L’viv’s 2018 march consisted of hundreds giving coordinated Nazi salutes. JTA report.

March in Ukraine, historical; SS-Volunteer Division “Galician” memorial march in Lviv, Ukraine, 2014. Photo by Wikimeda Commons

For monuments to Ukrainian Nazi collaborators outside of Ukraine, see the U.S., Canada and Australia sections.

Ukraine is erecting new plaques and monuments to Nazi collaborators on a nearly weekly basis. Eduard Dolinsky of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee chronicles this explosion of Nazi collaborator whitewashing on Twitter, and wrote about it in The New York Times. For more on Ukraine’s state-sponsored Holocaust revisionism see the Nation, Foreign Policy, Open Democracy, a press release from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and Defending History’s Ukraine page.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Lev Golinkin is the author of A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka, Amazon’s Debut of the Month, a Barnes & Noble’s Discover Great New Writers program selection, and winner of the Premio Salerno Libro d’Europa. Mr. Golinkin, a graduate of Boston College, came to the US as a child refugee from the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkov (now called Kharkiv) in 1990. His writing on the Ukraine crisis, Russia, the far right, and immigrant and refugee identity has appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, CNN, NBC, The Boston Globe, Politico Europe, and Time.com, among others; he has been interviewed by MSNBC, NPR, ABC Radio, WSJ Live and HuffPost Live.

Featured image: Bandera memorials in Ukraine. Photo by Wikimedia Commons