How the Decisions to Nix Certain Monoclonal Antibodies Were Made

A comprehensive description of how a key COVID-19 treatment has been treated by regulators

Monoclonal antibodies have had their share of ups and downs in the timeline of COVID-19 treatments—but according to news headlines spanning the past two years—not nearly as much as some of the other off-label drugs like ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Most of the controversy, if any at all, began at the end of last year, when a handful of preprints written by quite a few scientists said certain brands of monoclonal antibodies would not work for the Omicron variant.

The State of Florida was using sotrovimab—one of the drugs that lost its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in January. Meanwhile companies like Eli Lilly (partnered with AbCellera and AstraZeneca) were poised to benefit with exclusive authorizations. The losers for the U.S. monoclonal markets became Regeneron, who makes REGEN-COV, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) partnered with Vir Biotechnology—the maker of sotrovimab.

Yet people can still get monoclonal antibodies if they are available in their regions and states, and there are still pharmaceutical companies across the globe whose emergency use permits have not been revoked. Eli Lilly still has one more monoclonal antibody product in the game, and had to add another monoclonal antibody to another for more potency. The company conceded to the FDA’s decision. Regeneron vowed to tweak its formula to make it Omicron-resistant, while GSK/Vir rushed to prove their product indeed works for Omicron, and that the science used to edge out the competition was not clinically valid.

Stories on monoclonal antibodies may not be in the mainstream news very often, but it’s top of the page on pharmaceutical publications, and has even more of a place in articles on pharmaceutical industry stocks and industry deals with high-income nations. Those involved in the top tiers of health policy say that with changing variants, treatments need to be current with the new strains. When Regeneron and GSK/Vir lost their EUA, most policy makers just kind of shrugged their shoulders and moved on to COVID-19 drugs like remdesivir. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded remdesivir’s authorization to outpatient treatment and pediatric patients this January.

However, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis said it was possible Florida could take legal action to bring the revoked monoclonal antibody treatments back. DeSantis referenced President Joe Biden when he tweeted, “Floridians have benefitted from the state’s treatment sites and their access to treatment shouldn’t be denied based on the whims of a floundering president.”

Pandemic response critics may not be focused on monoclonal antibodies, but many group them into the alternative treatment soup. Critics say that any treatment that isn’t a vaccine is automatically stifled or publicly scrutinized as unsafe or ineffective.

During a December 2021 interview with podcaster Joe Rogan, Dr. Peter McCullough, a cardiologist, and one of the most published authors of peer-reviewed journals in his field, said he thinks there was, “an intentional, very comprehensive suppression” of early treatments to “promote fear, suffering, isolation, hospitalization, and death.”

A Different Kind of Treatment

In August of 2021, Florida newspapers reported the opening of monoclonal antibody clinics across the state. The viral photo people saw on the news was a moaning, crying, immobile woman, lying on the floor while waiting in line at a Jacksonville monoclonal antibody site. Without much information to go on, this desperate image has become the poster child of monoclonal antibodies.

Nobody wanted to be as sick as that woman on the floor, but at the same time, very few people understood what exactly that treatment was at the end of the line—monoclonal antibodies may be one of the least understood treatments on the market. People know these treatments are experimental, but their mechanisms and origins are certainly not common knowledge.

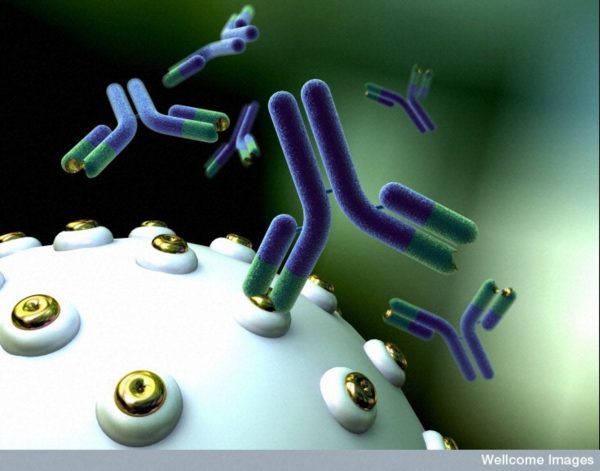

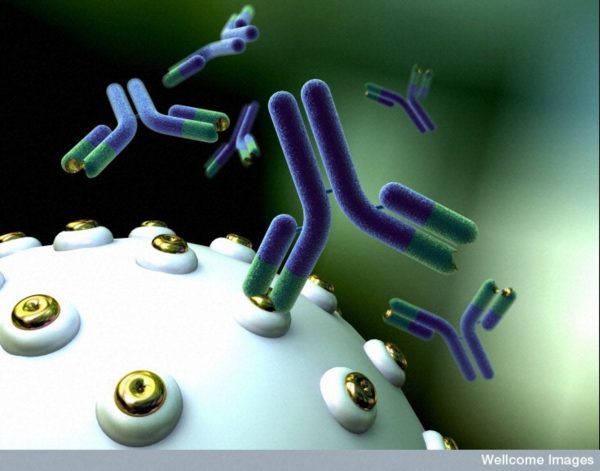

“Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off harmful pathogens, such as viruses like SARS-CoV-2,” as explained by the FDA. They come with especially strange names that can be easily confused with the names of antibiotics and steroids in the wax and wane of COVID-19 treatments and therapies.

It’s a competitive market—and one that relies heavily on the latest science and clinical trials, as well as emergency approval from governments and nations.

If they can find them in their state despite complications and contracts, Americans who are as sick from COVID as the woman on the floor have only two left to choose from: Eli Lilly/AbCellera’s bebtelovimab or AstroZeneca’s Evusheld tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

Monoclonal antibody treatments can be effective in the short-term. Most company studies and reviews in major publications showed a reduced risk of hospitalization and death in the 60–85 percent range.

The most important study showing monoclonal antibodies were working and keeping people from the hospital was the University of Oxford randomized evaluation trial released in June 2021 (aka the RECOVERY trial), which demonstrated Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody combination reduced viral load, shortened the time to resolution of symptoms, and significantly reduced the risk of hospitalization or death.

Joint Chief Investigator Sir Martin Landray said in a University of Oxford article, “There was great uncertainty about the value of antiviral therapies in late-stage COVID-19 disease,” he said, “It is wonderful to learn that even in advanced COVID-19 disease, targeting the virus can reduce mortality in patients who have failed to mount an antibody response of their own.”

Products and Partnerships

In the world of monoclonal antibodies, there have been about seven major players:

AbCellera/Eli Lilly’s bamlanivimab with etesevimab, which are administered together, were given an EUA in November 2020, and bamlanivimab (alone) had its revoked in April 2021 when clinical trials found adverse reactions including anaphylaxis and vasovagal reactions, as well as waning effectiveness. The FDA said in a statement, “Although the FDA is now revoking this EUA, alternative monoclonal antibody therapies remain available under EUA, including REGEN-COV (casirivimab and imdevimab administered together) and bamlanivimab and estesevimab, administered together, for the same uses as previously authorized for bamlanivimab alone.”

Eli Lilly’s bebtelovimab, discovered by AbCellera and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center, was given an EUA in February 2022.

Regeneron’s REGEN-COV casirivimab/imdevimab combo was approved for an EUA in the United States in January 2020 and revoked in January 2022. Roche’s Ronapreve casirivimab/imdevimab, which was jointly developed with Regeneron, began emergency permits for use in Japan in July 2021 and additionally casirivimab/imdevimab combinations continue to be offered in the European Union, United Kingdom, India, Switzerland, Canada, and Australia.

In 2020, Roche entered into a number of new partnerships, including with Gilead, who makes Veklury (remdesivir). Remdesivir was the only FDA approved drug treatment for COVID-19, as opposed to treatments and drugs on experimental EUA authorizations (other than Pfizer-BioNTech’s Comirnaty COVID-19 vaccine, which is fully licensed, but unavailable in the United States), and as of January, the only drug approved for pediatric patients.

Also still under EUA is AstraZeneca’s Evusheld (tixagevimab/cilgavimab), approved December 2021, which is for the prevention, rather than treatment, of COVID-19, specifically designated for patients with moderate to severely compromised immune systems and whom have a history of severe adverse reactions to a COVID-19 vaccine.

Celltrion’s Regkirona regdanvimab is an approved EUA monoclonal antibody treatment in South Korea, Europe, Indonesia, Brazil, Peru, and Australia. It became the fifth COVID-19 treatment to receive provisional Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approval in Australia in December of 2021.

The most well-distributed monoclonal antibody treatment is GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Vir Biotechnology’s Xevudy sotrovimab, provisionally authorized in the European Union. The FDA issued an EUA for sotrovimab in May of 2021 and revoked the EUA in February in geographic regions like where infections were likely caused by the Omicron variant. By April, sotrovimab had been revoked in every state. This is one of the brands Florida was using for its monoclonal antibody clinics when the big change was made.

The Variant Shift

When preprints of studies found that existing monoclonal antibodies may not be effective for variants like Omicron, everything changed.

All the players who had an EUA approved for their monoclonal antibody faced a reckoning of sorts in January, when nearly all of the monoclonal antibodies used to prevent disease failed to stand up to laboratory assays, as detailed in four non-peer reviewed preprints from December 7–14, supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. A number of international researchers asserted the Omicron variant may be totally or partially resistant to most currently available monoclonal antibody treatments.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) is listed as the supporter of the aforementioned preprints, and had committed $25 million to the Coronavirus Treatment Acceleration Program (CTAP) in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and others. CZI’s co-founders are Dr. Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg. A spokesperson for the company announced on December 7, 2021 that CZI would invest up to $3.4 billion for “advances in human health,” which include a separate $1 billion for the “Chan Zuckerberg Biohub,” which aims to develop disease treatment technologies.

Amid the preprint reports that the COVID-19 antibody treatment from Regeneron had lost its effectiveness against the Omicron variant, GSK and Vir made a statement to investors and media in December 2021 that their antibody drug was effective against all 37 mutations as identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, plus others, including Delta, Delta Plus, Mu, and Omicron, citing new, pre-clinical data from early-stage studies.

Despite that apparent effectiveness, monoclonal antibodies companies were already losing their places on the treatment field.

On January 24, Dr. Gerald Harmon, President of the American Medical Association released a statement after the FDA revised the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to block Eli Lilly’s bamlanivimab-estevimab and Regeneron’s REGEN-COV monoclonal antibody treatments in the United States.

“Given the latest data showing the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for 99 percent of current COVID-19 infections, we are pleased that the FDA is following the scientific evidence and limiting the use of monoclonal antibody treatments to those that are effective against the Omicron variant,” said Harmon.

“Limiting the use of these treatments will help ensure patients receive the best available therapy. We encourage physicians to reference the current National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment guidelines for the latest information on authorized therapies and recommendations for their use.”

Florida Disagrees

The announcement was confusing for several reasons: First, states like Florida, which had the most robust monoclonal antibody clinic and hospital program of any state in the United States, had been working from a Standing Order for Regeneron’s REGEN-COV, Eli Lilly’s bamlanivimab and etesevimab combination, and GSK/Vir Biotechnology’s sotrovimab for the treatment and post-exposure prophylactic use for COVID-19.

Floridians who felt sick with COVID-19 could go to a nearby site and get monoclonal antibody treatment, free of charge and without a prescription. With their offered monoclonal antibodies revoked and unauthorized, now the state would have to involve themselves in another contract process to offer Eli Lilly/AbCellera’s bebtelovimab or AstraZeneca’s Evusheld for the immunocompromised or vaccine-intolerant.

In response to the change, Florida Department of Health released a statement on January 24 that all monoclonal antibody state sites will be closed until further notice.

The Communications office said, “Florida disagrees with the decision that blocks access to any available treatments in the absence of clinical evidence. To date, such clinical evidence has not been provided by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).”

The Florida Department of Health had been correct. There had been no clinical evidence—just pre-prints supported by Zuckerberg’s CZI.

Dismissing the non-peer reviewed preprints, Florida Health added, “As stated in one of the preprint studies cited on the NIH website, “despite observing differences in neutralizing activity with certain mAbs (monoclonal antibodies), it remains to be determined how this finding translates into effects on clinical protection against B.1.1.529 (Omicron).”

The second reason people were confused is because the average citizen is unclear on what exactly monoclonal antibodies are. Descriptions on the news have been vague. People hear that when a monoclonal antibody is injected into the body, it binds to the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2, consequently blocking cellular entry and COVID-19 infection.

Basically, the information people are given, is that they make you feel better if you get sick with COVID. You have to get it right away—within the first ten days—and it’s made of antibodies. The antibodies get injected straight into a person’s system and keep the spike protein from entering the cells. Most publications describe monoclonal antibodies as a precision immune booster, a last resort for when you become sick, but not sick enough for the hospital.

The third reason people were confused is because they didn’t know if monoclonal antibodies were safe. People didn’t have the information to know or be convinced that a treatment they hadn’t heard of before the pandemic was safe, and a great many of them had lost trust in their government and institutions offering the treatment.

According to The Times of Israel, when Israel began to widely administer Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody treatment last September, almost half of the country’s eligible population rejected the introduction of monoclonal antibodies. “Some eligible 400 patients have refused to take it,” The Times said, even when the expensive treatment was covered by their HMO.

But why? Because the treatment has the word “clone” in the name? Is it some sort of gene splicing experiment, some wondered? Were the Israeli people concerned that the product has similarities to gene manipulation? And what are the ethical concerns of production?

A Repurposed Drug Treatment

Monoclonal antibodies technology is not new. The treatments have been around for nearly 50 years. The use of monoclonal antibodies in pharmaceuticals began in 1975 at the Laboratory for Molecular Biology in England when researchers developed a way to create cells that could pump out streams of identical antibodies. In the ’80s, monoclonal antibodies were used in diagnostics for pregnancy tests, and approved in the late ’90s for targeted therapies for a wide range of diseases and disorders, from cancer to psoriasis.

In 2019, seven of the 10 best-selling new drugs were monoclonal antibodies for cancer and inflammatory diseases, with more than 570 mAbs currently in clinical testing. One of the most well-known monoclonal antibody treatments is the rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira. Monoclonal antibodies are used globally, with 80 percent sold in the United States, Europe, and Canada.

Like many treatments during the pandemic, recommendations and approvals came and went depending on many complex factors—and not without controversy.

Promising trials for monoclonal antibodies in the early months of the pandemic led to emergency use authorization (EUA) in the United States for Regenoron’s monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab and Eli Lilly/AbCellera’s drug bamlanivimab.

Many other pharmaceutical companies began Phase II and III trials, Vir and GlaxoSmithKline, Brii, Sorento, and AstraZeneca. Initial evidence from Regeneron and Eli Lilly indicated their drugs decreased hospitalizations and medical visits, and reduced viral loads for outpatients in the early stages of disease and worked best in high-risk patients with low native antibody response.

Additional efforts to study potential impact on transmission were underway, and due to the nature of the intravenous formulation, clinical and logistical challenges were analyzed.

Some of the most prominent front line doctors and scientists during the pandemic have supported monoclonal antibodies as a viable early treatment for COVID-19.

Where do Monoclonal Antibodies Come From?

Monoclonal antibodies have been described to the public as a 30-minute injection of purified, laboratory-produced molecules that act as substitute antibodies. To most, this sounds pretty benign, and no one seemed to be sounding the alarm that monoclonal antibodies are unsafe, despite the emergency approvals they’ve relied upon.

Antibodies are derived from living organisms—but which organisms?

If you read one of the many articles on monoclonal antibodies, the explanation usually begins with point A: the lab-produced substitute antibody. But the antibody in the IV bag is really point B.

According to an article by a monoclonal antibody manufacturer, a typical monoclonal antibody production process begins with mice vaccination. In order for the mice to have COVID-19, it must be injected with the vaccine that carries the antigen.

The article states, “Mice are immunized with an antigen and later their blood is screened for antibody production. The antibody-producing splenocytes are then isolated for in vitro hybridoma production.”

Next, the myeloma cells are prepared and after a fusion process, are formed into hybridomas (cultures of hybrid cells). Then the clones are screened and selected on the basis of antigen specificity and immunoglobulin class, characterized, scaled up, weaned off, and finally expanded into desired antibodies.

So after point A, and point B, we have point C: a time of action for the new antibody.

The FDA information site describes point C as the time when the antibodies “may block the virus that causes COVID-19 from attaching to human cells, making it more difficult for the virus to reproduce and cause harm. Monoclonal antibodies may also neutralize a virus.”

Then we have point D, the time after a person ideally recovers. We don’t really know much about point D—or how the immune system will welcome new synthetic antibodies. Due to the treatment being experimental, we don’t have long-term studies to determine exactly what point D looks like. Time will tell, however Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Allergy and Infectious Diseases endorses the treatment.

Fauci said during a White House briefing in August, 2021, “We recommend strongly that we utilize this to its fullest,” calling monoclonal antibody treatment “effective” yet “underutilized” by most physicians treating the early cases of the virus.

The Regeneron monoclonal antibodies (REGEN-COV) use a similar mice vaccination process, according to a July 2021 Nature study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The study explains that Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, the New York-based biotechnology company that produces REGEN-COV monoclonal antibodies for COVID, uses human antibodies obtained from transgenic (organism with artificial DNA from an unrelated organism) human antibody mice, containing “two fully human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibodies, one selected from the Velocimmune mouse platform and the other isolated from human subjects.”

According to an FDA reference paper (with redactions), the Regeneron formula is not just antibodies from vaccinated transgenic mice ovaries. It also contains a redacted percentage of histidine (a “possibly” safe amino acid, according to the FDA), and 0.1 percent polysorbate 80 per dose.

An article on the Regeneron monoclonal antibody cocktail explains the manufacturing process as one that begins with “a mammalian cell line called Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells.” The article states, “Regeneron core technologies enable the rapid and efficient generation of these protective antiviral mAbs outside the body, derived from genetically humanized mice or convalescent (sick/recovered) humans.”

Among the other monoclonal antibodies in circulation Eli Lilly/AbCellera’s Bebtelovimab also contains polysorbate 80 (0.5 mg per dose). Polysorbate 80 has been associated with an increased risk of systemic adverse reactions. GSK/Vir’s sotrovimabis also produced by a Chinese Hamster Ovary cell line.

Whether people have informed consent that their monoclonal antibody treatment involves “genetically humanized mice,” monoclonal antibodies continue to be utilized across the world as an emerging technology.

Moreover, according to a paper titled “Mouse Models for Drug Discovery: Can New Tools and Technology Improve Translational Power,” published in Oxford University Press, 2016, the use of mutant mouse models in biomedical research and preclinical drug evaluation is on the rise, especially with the advent of molecular genome-altering technologies such as CRISPR.

Support for Monoclonal Antibodies

Prominent figures and heads of state have recovered from COVID-19 with the concurrent use of monoclonal antibodies. President Donald Trump recovered from COVID-19 using several treatments, including monoclonal antibodies, remdesivir, steroids, vitamins, and zinc.

Podcaster Joe Rogan recovered from COVID-19 using monoclonal antibodies, ivermectin, Z-pac, steroids, and what he called “the kitchen sink.”

Even as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis expanded the monoclonal antibodies program across the state, not much was written about monoclonal antibodies by the media.

Even CNN writer Jen Christensen treated it with her “nice” gloves, writing that monoclonal antibodies work, but they’re “not the path out of this pandemic.” The most provocative thing she could say is that it’s a “conservative” thing, due to its reliance on therapy from President Trump, Texas Governor Greg Abbott, and Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City.

Monoclonal antibodies are challenging to manufacture, time-consuming, and expensive, but DeSantis made these treatments free for his citizens.

At the time, in Florida, the news barely reported that clinics were opened as COVID-19 treatment centers, and many left out the words “monoclonal antibodies” in the headlines. Yet despite little press on the subject, and possibly not the fullest understanding of what the treatment they were getting actually was, Florida citizens flocked to the clinics for treatments.

Not much curiosity from TV stations, but in September of 2021, The Highwire featured the piece, “Is Monoclonal Antibody Treatment Saving Lives?”

Prepping the topic, Highwire host Del Bigtree said hydroxychloroquine had become a “political football” and ivermectin is entrenched in battles. Then he asked the big question, “Is there a treatment that anybody likes?” He wondered about that treatment he has heard a little about: monoclonal antibodies.

Bigtree brought on emergency room physician and general practitioner Dr. Richard Bartlett, who was treating patients with Regeneron (casirivimab and imdevimab) monoclonal antibodies in West Texas at the time.

Regeneron’s monoclonal antibodies are the same brand which President Trump received.

“Monoclonal antibodies are not new technology. It’s not something Bill Gates cooked up just the other day,” Bartlett said, after wishing he had treatment access sooner for his patients. He said from “boots on the ground” experience, he’d seen monoclonal antibodies save lives. “This is something that’s real science. What I’m seeing is that in 30 minutes, sitting in a chair—very boring—getting an IV, and their chest pain is going away. Their chest tightness is going away. Their back pain is stopping. The headache, that they’ve had for five days non-stop goes away. They are seeing tremendous results.”

Bartlett said that unlike plasma, monoclonal antibodies have less of a risk of infection because it is a “purified antibody product.” He said he hadn’t seen any adverse reactions in his patients as of the interview.

During the time of interview, the world was mostly seeing the Delta variant. Bigtree could see this could turn into a problem.

He asked Bartlett, if these antibodies were designed for the original strain, would they work for future variants?

“The bottom line is I’m seeing great results. We’ve seen articles that it can prevent over 70 percent of hospitalizations and deaths. This is a game changer,” responded Bartlett.

Bartlett mentioned he also found budesonide, a steroid, to be an additional, highly effective co-treatment for COVID-19. He also uses an aspirin a day for his protocol, to prevent blood clots, and antibiotics such as clarithromycin, ivermectin, and supplemental oxygen, depending on each patient’s individual needs.

Besides monoclonal antibodies, Bartlett added, there are other strategies that work. “It’s all hands on deck when you’re dealing with this,” he said, “and these treatments are not mutually exclusive.”

Problems with Monoclonal Antibodies

According to the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC), the guidance approach on monoclonal antibodies by agencies such at the FDA is “complex” and “confusing.”

“We are unable to identify a consistent approach to the strength and timing of NIH recommendations and/or updates to the recommendations,” the FLCCC stated in an article on National Institutes of Health (NIH), FDA, and WHO recommendations on monoclonal antibodies, ivermectin, convalescent plasma, remdesivir, anti-IL-6 therapy.

And while monoclonal antibodies have seen their share of revisions in EUA authorizations that confuse professionals wanting to administer alternatives, some say the process has become political.

While testifying at the Pennsylvania House of Representatives last year, Dr. Pierre Kory, a pulmonary and critical care specialist and president of the FLCCC, said a war on off-patent, FDA, approved, inexpensive, safe, “repurposed drugs” has been waged by the pharmaceutical industry for decades in an attempt to preserve profits for novel, patented, high profit drugs.

Kory said, “The reality as to why these medications are ignored and not recommended is quite simple; we live in a healthcare system that is structured to favor novel, highly profitable, pharmaceutically engineered compounds over compounds that have well-established safety profiles, yet little profit to be made … I’ve had a front row seat to the latest battles in that war during COVID-19 and it has been one of the most profound sadnesses of my professional career.”

The American response to COVID-19, led by Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), became the subject of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s book, “The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health.”

In a chapter on “mismanaging the pandemic,” Kennedy wrote: “I was struck, during the COVID-19’s early months, that America’s Doctor, apparently preoccupied with his single vaccine solution, did little in the way of telling Americans how to bolster their immune response.”

He continued. “During the centuries that science has fruitlessly sought remedies against coronavirus (aka the common cold), only zinc has repeatedly proven its efficacy in peer-reviewed studies … Yet Anthony Fauci never advised Americans to increase zinc uptake following exposure to infection.”

Doctors have also voiced their concern with the timing of approvals and neutrality of recommendations. Bartlett said the key to the success of monoclonal antibody treatment has been early treatment. “That is what has been ignored, suppressed, and minimized, and censored, is early, effective outpatient treatment,” he said.

Early and effective treatment, outside of the hospital, can take several forms and needn’t be limited to vaccines and costly drugs like monoclonal antibodies. The financial windfall that COVID-19 represented for some interests has raised concerns about the relationship between profit-driven companies, private foundations, and governments.

“An increasingly clear feature of the COVID-19 pandemic is that the public health response is being driven not only by governments and multilateral institutions, such as the World Health Organization, but also by a welter of public-private partnerships involving drug companies and private foundations,” notes an article published in the BMJ, the influential journal of British Medical Association.

The Wellcome Trust, one of the world’s top funders of health research, became one of the leaders of the WHO program to support new COVID-19 therapeutics but also stood to gain financially from the pandemic, noted the articles author, independent journalist Tim Schwab.

“Wellcome’s financial interests have been published on the trust’s website and through financial regulatory filings but do not seem to have been disclosed as financial conflicts of interest in the context of Wellcome’s work on covid-19, even as they show that the trust is positioned to potentially gain from the pandemic financially.”

The article explains the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator project “hopes to raise billions of dollars and deliver hundreds of millions of treatment courses” during the COVID-19 treatment years, “including dexamethasone and a number of monoclonal antibodies.”

“Revelations of the Wellcome Trust’s financial conflicts of interest follow new reports that another charity, the Gates Foundation, is also positioned to potentially benefit financially from its leading role in the pandemic response,” Schwab writes.

Though efforts from The Wellcome Trust and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation focused on bringing monoclonal antibodies and vaccines to low- and middle-income nations that had not historically used monoclonal antibodies, many countries were interested in other therapies.

During the pandemic, reports of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) took a back seat to pharmaceutical products and vaccines, despite the fact many countries were using them to prevent and cure COVID-19.

A global perspective study (Elsevier, March 2021) finds CAM had been used for COVID-19 in more than 25 percent of patients in India, as well as up to 80 percent of the population of Pakistan, as well as Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and Maldives.

A survey from the same paper found 22 percent of Saudi Arabians used CAM such as chamomile and garlic to prevent COVID-19. Eighty-percent of the African populations and communities in South America, Europe, and North America used CAM according to the WHO.

The usage of monoclonal antibodies across the globe may take a few new twists and turns, and the questions people may have on whether the treatment is on the good or bad side may need further investigation.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Epoch Times can be found here.