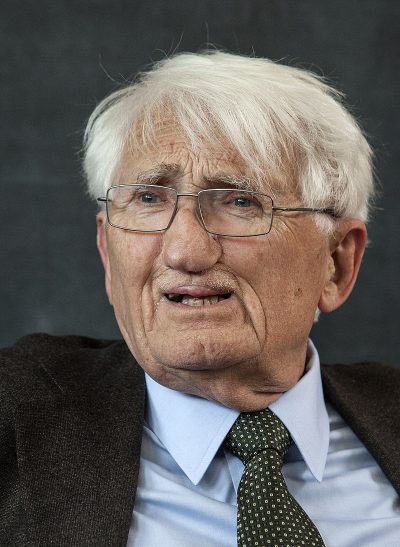

Jürgen Habermas on the War in Ukraine: “The conversion of former pacifists leads to mistakes and misunderstandings”

Understandably, emotions run high in a war. However, prominent German philosopher Jürgen Habermas calls on us: “let’s not allow ourselves to be guided by warmongering or a politics of fear”. He insists on reasonableness and “comprehensive consideration”.

The end of German pacifism

One of the most remarkable and unexpected events of this war is Germany’s radical turn regarding armaments and war efforts. The country has no real war industry, in the past it spent relatively little on armaments and in military conflicts the government has generally been very moderate. Just think of Iraq in 2003 or Libya in 2011.

From a historical point of view, that is more than understandable and sensible. In the past, the militarization of Germany has twice led to a global conflagration resulting in tens of millions of deaths. Therefore, it is better not to go back to that situation.

There is a second reason for the German reluctance to be involved in the current conflict. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, German capital was poured into Eastern and Central Europe. Strong economic ties were forged with Russia, among others.

Outside the European Union, Russia was until recently the fourth most important country for German imports and the fifth most important country for the export of German goods. The Germans are particularly dependent on the Russians in terms of energy: for gas that dependency is 32 percent, for oil it is 34 percent and for coal it is 53 percent.

German capital therefore has nothing to gain from a protracted conflict, let alone from an escalation, on the contrary. Conversely, it is especially the US that has an interest in this. At least that’s how Willy Claes, a former NATO-boss, sees it. According to him, this conflict is essentially about a “confrontation between Russia and America” in which “Europe is not involved”. He notes that the US it “will not mind it taking a while”.[1]

At the outset of the invasion, for the two reasons cited, the Federal Government was particularly reticent, much to the chagrin of countries such as the US, UK and the eastern states of the European Union. They put pressure on Chancellor Scholz to shake off this reticence.

The pressure exerted by the media was even greater. Due to the fact that almost everyone now has a smartphone, this is the most mediatized war in world history. We are able to follow the appalling suffering in this war online with the most horrific details, so to speak, and that arouses a lot of emotions, even far away from the battlefield.

In addition, the mainstream media use the Hollywood framing of ‘the good versus the bad’. Such a framing is excellent for viewing and reading figures, and moreover it raises the emotions in public opinion. Such reporting however, leaves no room for nuance or for balanced approaches such as those of the German government at the outset of the conflict.

Eventually, Olaf Scholz gave in to the great pressure and that was the end of a pacifist foreign policy that had lasted for the past 75 years. Germany will spend no less than 100 billion euros extra on armaments in the coming years and promises have also been made for arms supplies to Ukraine.

An ugly dilemma

It is against this pressure on the German chancellor and the break with the pacifist past that Jürgen Habermas has written a noteworthy op-ed piece in the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Habermas is Germany’s most prominent and respected philosopher, pretty much the Noam Chomsky of Germany.

The 92-year-old philosopher outlines the ugly dilemma facing the West: either a defeat in Ukraine or the escalation of a limited conflict that could turn into a Third World War. In this “space between two evils”, the West has chosen not to participate directly in this war.

For Habermas, this is a wise decision because “the lesson we have learned from the Cold War is that a war against a nuclear power can no longer be reasonably ‘won’, at least not by military force”.

The problem with this is that Putin then determines

“when the West crosses the threshold set by international law, beyond which he will also formally consider military aid to Ukraine to be the start of a war by the West. This gives the Russian side an asymmetrical advantage over NATO, which does not want to become a war party because of the apocalyptic proportions of a world war involving four nuclear powers.”[2]

On the other hand, the West “cannot accept being blackmailed randomly. If the West simply left Ukraine to its own devices, this would not only be a scandal from a political and moral point of view, it would also not be in its own interest.” The scenario of what happened in Georgia and Moldova[3] could then repeat itself and, Habermas wonders, “who would be next”?

Within this uneasy setting, Habermas is glad that the German chancellor is not guided by a “politics of fear” and that he is pushing for a “politically responsible and comprehensive consideration”.

Scholz himself summarized his policy in Der Spiegel as follows:

“We confront the suffering that Russia is causing in Ukraine by any means necessary without causing an uncontrollable escalation that causes immeasurable suffering across the continent, perhaps even the entire world.”

Warmongers

But Scholz is under a lot of pressure. He faces a “fierce battle of ideas, fuelled by press voices, over the nature and extent of military support to a ravaged Ukraine.” In addition, the main protagonist, President Zelensky, is a talented actor, “who knows the power of images and delivers powerful messages”. The “political misconceptions and wrong decisions of previous German governments” are thus easily weaponized for “moral blackmail”.

Habermas here refers on the one hand to the continuation of the policy of detente after the fall of the Soviet Union, even when Putin had become unpredictable, and on the other hand to dependence on cheap Russian oil.

This moral blackmail has

“ripped the young away from their pacifist illusions”. He explicitly refers to Annalena Baerbock, the young foreign minister of the Greens, “who has become an icon, who immediately after the start of the war gave authentic expression to the shock with credible gestures and confessional rhetoric”.

Three days after the invasion, Baerbock gave an emotional speech to the German parliament. As in other countries, the German Greens have strong roots in the peace movement. It was therefore more than significant that it was mainly the German Greens who insisted within the government for more and faster arms deliveries.

Habermas is particularly irritated by the “belligerent rhetoric” and “the self-assuredness with which the morally indignant accusers in Germany act against a thoughtful and reticent federal government”. They are hounding the chancellor with “short-sighted demands”.

“The conversion of the former pacifists” according to Habermas “leads to mistakes and misunderstandings”, and he perceives a “confusion of feelings”. These “agitated opponents of the government line… are inconsistent in negating the implications of a policy decision they do not question.”[4]

Scholz has kept a cool head for the time being. He has had to make concessions, but he continues to steer a cautious and moderate course, especially when compared to the bellicose stance of the US or Britain. Germany has promised to increase its arms supplies to Ukraine, but these are promises and their implementation has been slow.

Unlike hawkish countries such as the US, UK and the Baltic States, France, Germany and Italy maintain an open dialogue with Russia. For example, Scholz and Macron had a telephone conversation with Putin to negotiate, among other things, about unblocking Ukraine’s food exports.

Putin

Habermas also resents the “focus on Putin as a person”. That “leads to wild speculation, which our leading media spread today, just as in the heydays of speculative Sovietology.”

The media portrays “an erratic visionary” who sees “gradual restoration of the Great Russian Empire as his political life’s work”. “This personality profile of an insanely driven historical nostalgic contrasts with a track record of social progress and the career of a rational and calculated strongman”.

Habermas interprets the invasion of Ukraine “as a frustrated response to the West’s refusal to negotiate Putin’s geopolitical agenda”.

For Habermas, Putin is “a war criminal” who deserves having to appear before the International Criminal Court. But at the same time, he notes that the Russian president still has veto power in the Security Council and that he can threaten his opponents with nuclear weapons.

Like it or not, it will be with him that we will “need to negotiate an end to the war, or at least a truce”.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Translated by Dirk Nimmegeers.

Source

Jürgen Habermas unterstützt abwägende Haltung des Bundeskanzlers, Der Spiegel.

Notes

[1] Willy Claes in Belgian TV programme De Afspraak of 24 May: “If I may say it a little boldly, it is about a confrontation now between Russia and America. With all due respect and sympathy for the Ukrainians, and by the way, Europe is not playing along. … In conclusion, the Americans will not object it taking a while. … It’s a golden age for the war industry, which is by definition American.”

[2] The US, France, Great Britain and Russia.

[3] In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia to support the self-proclaimed republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia it backed in their conflict with Georgia’s central authorities. After a ceasefire, the Russians withdrew but maintained a security zone in the conflict zones. A similar scenario had previously occurred in Moldova in the period 1990-1992.

[4] NATO’s choice not to be directly involved in this war.

Featured image is licensed under CC BY 2.0

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Global Research can be found here.