How Secret Soviet Killings Led to COVID Tyranny

June 12, 2022

As the mournful notes of the cello brought the four minutes of The Dying Swan to a close at The Hague on January 24, 1931, the audience was in tears. Throughout the performance, there had been no dancer — only a moving spotlight emphasizing the absence of Anna Pavlova, the ballerina the world loved. She had died the day before, of a mysterious lung infection that began almost immediately after her train had left Paris. She’d told doctors she suspected she’d been poisoned. Unable to reach a diagnosis, they treated her symptoms but failed to save her.

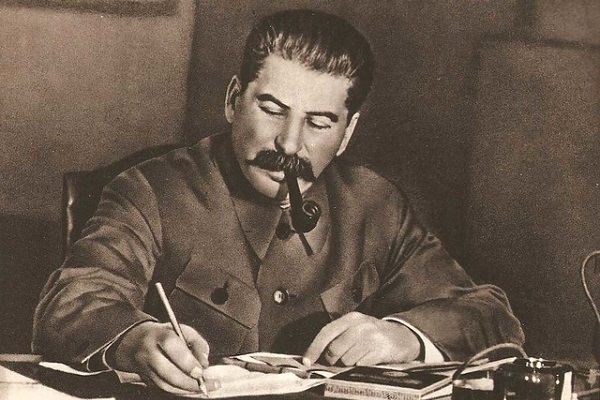

For Soviet émigrés of the time, the empty stage, the melancholic music, and the spotlight sans performer were poignant symbols of the hundreds of thousands of “liternoye” killings — secret, disguised liquidations staged as natural deaths or suicides — ordered by Joseph Stalin. His targets were not just rivals in the USSR, but also dissident writers, intellectuals, artists, and performers living abroad. In fact, from the 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, while Stalin was carrying out purges in the USSR, the émigré community witnessed several mysterious deaths and disappearances.

Stalin worked by the dictum “communism must eliminate what it cannot control.” “Liternoye” killings were different from the genocides and massacres he oversaw: the liquidation of kulaks, the Holodomor — deaths caused by famine-related decisions in Ukraine — and the purge of nationalities. Unlike those, “liternoye” killings resulted in deaths from seemingly natural causes. They would be followed by hasty disposal of bodies and either advantageous glorification (as for Lenin, a presumed victim of Stalin) or damnatio memoriae (complete erasure from the records and history). Quite often, hard-to-detect poisons and bioweapons were used for these murders.

In their fast-paced book, The Dancer and the Devil: Stalin, Pavlova and the Road to the Great Pandemic, authors John E. O’Neill and Sarah C. Wynne make the startling but plausible connection joining Pavlova’s death (note that it was from lung disease), communism’s century-old obsession with bioweapons, and the recent development of poisons and pathogens by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that culminated in the worldwide COVID pandemic.

The psychopathic Stalin’s fascination with torture and bioweapons can be gauged from two facts. He set up Lubyanka as the headquarters of the secret police, with a prison and torture cells. Lubyanka was also where the gulags and purges were planned. Not far from it, he created Laboratory One, a sophisticated center for research in poisons and bioweapons.

Stalin’s rise to leadership was through conscienceless, expedient actions. By 1922, he had become one of Lenin’s closest lieutenants, judged trustworthy and capable of carrying out the liquidation of rivals. Eventually, after facing an assassination attempt, Lenin came to suspect Stalin of having targeted him, for Stalin was known for a talent in stealth and for betraying or killing friends without qualms. So Lenin then favored Leon Trotsky. He dictated a testament for his wife to share with the Communist Party. It recommended Stalin’s removal. But Stalin learned of it and had the document suppressed. Shortly thereafter, Lenin died, and a little later, his family members, too. It was widely suspected that Stalin had hastened their departure with poison.

The authors painstakingly build their case for the Stalinist ideological lineage of the COVID pandemic and how Pavlova’s death is surely (if tenuously) connected to it. “Stalin” (translated as “man of steel”) was a self-given alias, modeled on his guru’s alias, “Lenin.” The choice reflects, and perhaps influenced, his unbending materialism and heartless actions.

Marxism, a materialistic philosophy, is based on class warfare and control of the means of production. But Stalin extended it into a dictatorial control by the party — meaning himself — of all aspects of people’s minds and existence. Language, literature, music, art, history, culture — everything must be subservient to the state. The Soviet state reduced the arts to agitprop and the glorification of the revolution. Many intellectuals and artists went abroad to avoid persecution and find the freedom in which creativity thrives. These émigrés — among them Pavlova and impresario producer Sergei Diaghilev — epitomized free, unbroken spirits. This displeased Stalin immensely, and he ordered many of them killed by his secret police. The book makes the death of the ethereal, swan-loving Pavlova as much a tragic icon of communism’s murder of the spiritual, artistic side of humankind as of Stalin’s “liternoye” killings.

About the same time as Pavlova was dying, Stalin planned the destruction of two cultural icons of pre-Bolshevik Russia: the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and the Gate of Resurrection. For he had sworn he would kill G-d, end the Orthodox Church’s hold over the minds and souls of the Russian people, and firmly establish a materialistic worldview. Thousands of clergymen and believers were shot or sent to gulags.

Meanwhile, Laboratory One and the Special Task Groups responsible for carrying out killings in and outside the USSR were perfecting a variety of methods using “untraceable” bacterial and viral material. Stalin had the top security echelon, Laboratory One operatives and their families, and many others who knew of these secret ops eliminated, to be replaced with a fresh crop of executioners and scientists. Despite all his paranoia, Stalin was poisoned in 1953, ending his plan for a nuclear strike on the West, a war that would have destroyed civilization. It also halted many more purges he had planned.

But evil has a life of its own, and thrives in a world that rejects the spiritual. Laboratory One grew in power, reach, and danger under newer generations of communist leaders. Several bioweapons labs were opened, producing weapons capable of killing millions. “Liternoye” killings were perfected, too, as demonstrated by the 1978 murder of dissident Bulgarian journalist Georgi Markov with a poisoned pellet shot from a pneumatic device rigged in an umbrella. Though the Soviets pledged not to develop bioweapons under the 1972 Biological Warfare Convention, they spent billions on them through the 1970s to the 1990s. President Vladimir Putin pursues the poisoning of opponents and the development of biological weapons of mass destruction with zeal.

When the CCP took over China in 1949 with Stalin’s help, a slow osmosis of Stalinism, and with it, the ideology driving Laboratory One, began. Chairman Mao Zedong imitated the Soviet slaughters with his Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. The People’s Republic of China, which worshiped Stalin, began a biowar program that has developed deadly toxins and viruses. With Russian cooperation, the program was thriving by the 1960s. Since then, China has weaponized Marburg fever and the Ebola and SARS viruses.

The world first became aware of China’s bioweapons capabilities in 2005, when it offered assistance to Iran’s bioweapons program. Now, with at least fifteen identified facilities, it is believed to have the world’s largest and most sophisticated bioweapons capability. Five months before the COVID outbreak, the Pentagon had warned that China had a vast chemical- and bio-warfare program. The outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever and COVID have been characterized as inadvertent leaks, but who trusts China? Or trusts its supreme leader, Xi Jinping, who, like Stalin and Putin, has initiated purges, has ordered genocides (of Falun Gong, Uyghurs, and Tibetans), has murdered dissidents, and won’t hesitate to use bioterror?

China’s COVID cover-up has included the destruction of forensic samples, the mysterious deaths or disappearances of scientists who exposed the Wuhan lab’s work, and an iron control of the narrative. Xi joins the ranks of the greatest killers and cover-up artists in human history. Stalinism inspires inhumanity in its worshipers, as it has in Putin and Xi. The Dancer and the Devil traces the length of that dark and demonic reality — from Pavlova to the COVID pandemic.

Image via Flickr, public domain.