Madness, Part 4: Pursuit Of Justice

Ben: Val Orlikow went to the Allan in 1956 for postpartum depression.

The treatment left her mentally shattered and her family in financial ruin. Under the guise of being treated, she’d become the victim of experiments that were funded in part by the CIA — electroshocks, recordings played on loop for hours on end, and injections of LSD.

Val Orlikow: Things became very furry and very frightening. Nobody explained it to me. Nobody ever asked me if I was willing to do it or anything.

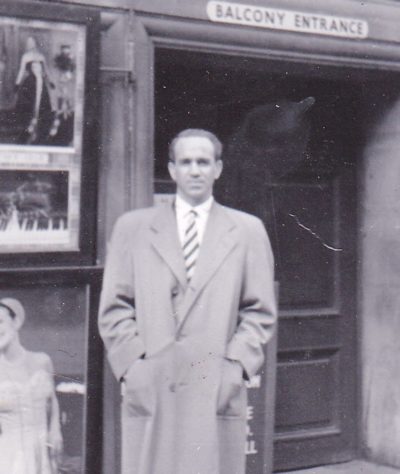

Amory: Val decided to fight back, to sue the CIA, and hold the agency accountable for experiments it had funded at the Allan. But a Canadian housewife taking on the CIA was a David vs. Goliath match-up. And it started with an actual David, Val’s husband, David Orlikow, who despite being a member of Canada’s parliament at the time, had a hard time even finding someone to take the case.

Ben: But he did eventually find a lawyer — a pair of them, actually — who were at least willing to try to take on the CIA: a renowned civil rights attorney in the U.S. — the late Joseph Rauh — and his up-and-coming professional partner, Jim Turner.

Jim Turner: I am an attorney. I practiced in Washington, D.C. for about 40 years.

Amory: Jim’s in his mid-sixties. He’s polite, direct, a down-to-business kind of guy. But you get the sense that if you gave him a couple beers, he could talk for hours about government scandals. Especially the government scandal he took on 40 years ago.

Jim: I spent a decade working on the case, more or less. And you kind of push a button and it comes out.

Ben: Jim was only in his mid-20s when David Orlikow came knocking. And yet, he was no stranger to CIA misconduct. He’d worked as a research assistant for the U.S. Senate’s Church Committee, which investigated government abuses of power, including the Watergate scandal, and yes, MK-ULTRA.

Jim: And when the Orlikows came to us with this case, it seemed to both of us that it was a very important matter that deserved public scrutiny on a couple of grounds, the most significant being that no part of our government should be above the law. Equally, that the folks who were so grievously injured should have some measure of recompense, even if it’s decades after the injuries were done.

Ben: Orlikow vs. United States was filed in 1980. It was a huge deal for Val, the plaintiff. Her granddaughter, Sarah Anne Johnson, says Val really struggled with the spotlight this case had suddenly put on her.

Sarah Anne Johnson: Every time she had to give an interview, every moment of it was painful for her. She would be so nervous and worried and uncomfortable. And my mom would have to go over to the house and pack her suitcase for her and help her get on the plane and she would try and back out every time. And it was very difficult for her to push herself through it. But she did it so that everybody would know what happened so that it could never happen again.

Amory: Although the case had Val Orlikow’s name on it, it included a handful of former patients of Dr. Cameron’s who came forward gradually and sometimes, reluctantly. Including Lou Weinstein, whose son Harvey says it took a year of trying to convince his father that what happened to him at the Allan wasn’t his fault.

Harvey Weinstein: I think I put it in the context of when a wrong is committed that one has a right to justice, and that he basically was assaulted by these medical practitioners. And secondly, that there was a conspiracy among intelligence agencies to experiment on vulnerable people and that he was a vulnerable person and that he had a right to be heard and to have his dignity restored to him.

Amory: Mental illness, especially in the days of Dr. Cameron, came with a lot of stigma. You didn’t talk about it, let alone try to take the U.S. government to court.

Ben: Val Orlikow and Lou Weinstein were two of what would become nine plaintiffs in the case, suing for a million dollars each. All former patients of Cameron’s who had received some combination of his depatterning and psychic driving techniques — psychedelics and sedatives, intense electroshocks, weeks or months of induced sleep, recordings played on loop.

Amory: We don’t know the total number of people who were treated at the Allan under Dr. Cameron’s direction. We know it was in the hundreds. And who knows how many of those people never learned about Cameron’s connection to the CIA. Or couldn’t remember what had happened to them. Or felt too ashamed to come forward. Or didn’t live to see the day that justice would finally be pursued.

Ben: But for the people pursuing that justice, there was a long road ahead.

(theme music plays)

Ben: I’m Ben Brock Johnson.

Amory: I’m Amory Sivertson, and you’re listening to Endless Thread. The show featuring stories found in the vast ecosystem of online communities called Reddit.

Ben: We’re coming to you from WBUR, Boston’s NPR station. And we’re bringing you Part 4 of a special series…

Amory: Madness: The Secret Mission for Mind Control and the People Who Paid the Price.

Ben: If you’re going to take on the CIA, you need a heavy hitter on your side. And Jim Turner had one: His legal partner, Joseph Rauh, had won prominent civil rights cases in the past. He’d defended Lillian Hellman and Arthur Miller before the anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee, and he’d had a hand in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Amory: But Jim says, even for Joe, suing the CIA on behalf of a small group of Canadian citizens was a daunting proposition.

Jim: You just can’t live your life being afraid. You got to do what’s right, and not be weak-willed. And neither Joe nor I were weak-willed.

Amory: It was going to take more than willpower. They needed to prove that the CIA was negligent in its funding of Ewen Cameron’s work, that there was a lack of oversight of dangerous experiments conducted without the consent of patients or their families, and that the CIA had tried to conceal its involvement with Cameron in the first place.

Jim: You’re suing an entity that is well-schooled in misdirection and in concealment, and that has, at its unilateral disposal, a whole set of national security objections that it can make to releasing information.

(music plays)

Ben: The CIA had already destroyed evidence of MK-ULTRA. But how would the intelligence agency avoid having to disclose what remained? By claiming that disclosing such evidence would put our national security at risk.

Amory: They were also good at concealing information within the agency. There were only a handful of employees at the CIA who had even known about MK-ULTRA at the time, and the ones who did were mostly prevented from testifying.

Jim: And when we would depose individuals who had knowledge, who had worked for the agency, they would interpose objections that were improper, instruct witnesses not to respond, even though they did not represent that witness. And that really, really dragged things out.

Amory: But Jim and his colleague had other arrows in the quiver. Including the testimony of several prominent psychiatrists, all of whom agreed that Cameron’s experimental procedures could not be considered “proper treatment,” or even treatment at all.

Jim: The bizarre combination of techniques that Cameron was employing in the Allan Memorial Institute were present nowhere else in the psychiatric community. And to not regard that as experimentation is to not have any meaning for the word experimentation. If you’re going to be getting something that is not standard care, you have a human right to know about it. And that was apparently of no concern either to Cameron or to the CIA who was funding him.

Ben: The lack of patient consent in Cameron’s experiments really was of no concern to the CIA. Not to the director of MK-ULTRA, Sidney Gottlieb, or to his deputy, Robert Lashbrook. How does Jim Turner know? They told him themselves in official court depositions.

Amory: Both Gottlieb and Lashbrook admitted in their depositions that they took zero steps to ensure Cameron’s experimentation was safe, or that it was being conducted on consenting volunteers. When Lashbrook was asked, “Did you ever at any time hear a conversation at the CIA concerning the question whether the persons who were experimented on must be told that they were being experimented on?” He answered…

Ben: “Not that I recall.”

Amory: Or, “Did you at any time make any suggestions on any projects on how to safeguard the experimentees?”

Ben: “It wasn’t felt necessary really to go into a lot of detail as to exactly how they were handling the subjects. In general, patients would be of low interest.”

Amory: Lead plaintiff Val Orlikow on ABC again.

Val Orlikow: I realize the CIA is a very important organization and they have a very important job to do, but God, it surely doesn’t have to be done on people who are totally incapable of knowing what’s happening or having any defense against it. And I can’t imagine the mentality of people who would do this. I just can’t.

(music plays)

Ben: An unexpected challenge to the plaintiffs’ case was the position taken by their very own Canadian government.

Amory: Now, you’d expect the Canadian government to be outraged over a foreign government funding experiments conducted on its citizens. But it turns out, The Canadian government had given Cameron even more money than the U.S. had. And when the CIA became aware of this, Canadian officials realized they had a problem on their hands. So they put together a commission to look at whether their government had acted improperly in funding Cameron’s work.

Jim: And they issued a report that could have been written by — and I expect was written by — the CIA’s lawyers.

Ben: That report concluded that the Canadian government was not legally liable for the outcome of Dr. Ewen Cameron’s experiments. Its release in 1986 was a huge blow to Jim Turner and his plaintiffs, who were already 6 years into their suit at this point.

Jim: And when I started negotiating with the U.S. attorneys, they said, we don’t have to negotiate with you. We’re going to hang the Canadian government’s involvement in this around your neck. You’re never gonna get a dime out of the CIA because the Canadians were doing it and they won’t stand up for their own citizens now.

(music plays)

Ben: Another key part of the case for Jim Turner was disproving the CIA’s position that Cameron had come to them unsolicited. Jim Turner’s team was able to get a deposition from a CIA official who said Cameron was recruited to do mind control experiments.

Amory: Which leads us to another challenge facing the prosecution: proving that Cameron’s so-called treatment regimen was a mind control experiment.

Ben: The proof was in a paper that Cameron had written in 1953, four years before the CIA started funding him. A paper buried in the boxes of Cameron’s papers archived at the American Psychiatric Association’s headquarters in Washington D.C, and unearthed by the son of one of the plaintiffs in the case, Harvey Weinstein.

Harvey: And in this paper, he talks about extraordinary political conversions that occurred in the Iron Curtain countries. But he says, quote, “We have explored this procedure, in one case, using sleeplessness, disinhibiting agents and hypnosis.” And my eureka moment was, here it is. He actually says that he was trying to do mind control experimentation and to use whatever he had at his disposal to do this.

Ben: So four years later, when the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology approached Cameron and said “How would you like more money at your disposal to do this work?” Cameron obliged. He applied for a grant from this CIA puppet organization and he got it.

Val Orlikow: He knew, he knew who he was working for and sometimes I can’t believe it. And yet I know it’s true.

Amory: Val Orlikow was sure that Dr. Cameron knew what he was doing and who was paying for it. We put that to Jim Turner.

Amory: There is no way to definitively prove one way or the other whether or not Cameron knew that, but–

Jim: So what!? So what? The CIA looked for a researcher who was doing research and experimentation that advanced brainwashing interests. It thought Cameron was doing that. He was doing it. He took money from them. They’re liable for it. I was never very concerned about Cameron’s own personal knowledge about Cameron’s own personal motive. The CIA knew they were giving him money and they knew they were getting results from him and he said that he wouldn’t be able to do the work without them in his last correspondence with them.

Ben: Jim is referring here to a letter that Cameron sent to the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology, calling their support “invaluable.”

Amory: Invaluable, perhaps, because it made it possible for Cameron to experiment on more of his patients, causing more harm to everyone involved.

Jim: These criminal misconduct kinds of crimes that happened under the MK-ULTRA program did not just have individual victims. There are entire intergenerational damages that were done to whole families and whole sets of people who had done nothing wrong, had done nothing to deserve this kind of governmental interference in their lives.

Ben: In January of 1988, nearly a decade after the case had been brought, Jim Turner got the call that a settlement had been reached in Orlikow vs. United States. The U.S. government would pay $750,000 to be divided among the now eight plaintiffs. One was disqualified on a technicality.

Amory: The Canadian government offered up an additional $20,000, totalling about $100,000 per victim. A far cry from the million dollars each plaintiff was seeking.

Jim: It’s a tough calculus when you’re trying to help people who are, some of them, just above indigency, living hand-to-mouth. But you’re also trying to get a meaningful settlement that can’t just be brushed off as, oh, we don’t admit any liability. Well, you don’t give somebody $750,000 if you haven’t done something.

Amory: I mean, true. And yet, that being said, they didn’t admit liability. And there was no apology.

Jim: Yeah, that’s part of the trade-offs. We talked about it. And in the final analysis, we thought it was more important to get compensation to people while they were still alive and could have some beneficial impact from the money than to demand an apology. People could come to a different conclusion on that.

Ben: People like the lead plaintiff, Val Orlikow. Val’s granddaughter Sarah Anne Johnson again.

Sarah: She wanted her day in court. She wanted a public apology. That was the most important thing to her more than the money.

Amory: Val died two years later, in 1990. To this day, neither the U.S. nor the Canadian government have ever officially apologized for funding experiments that were conducted without consent, and which amounted to medical malpractice and torture.

Ben: But now, a group of more than 300 people…

Amory: … and counting …

Ben: Are hoping to change that. More in a minute.

[Sponsor Break]

(Knocking on a door)

Marlene Levenson: Hi! Welcome!

Amory: Hello! Marlene? Marlene! I’m Amory.

Amory: It’s a grey October day in Montreal, and Ben and I have just arrived at the apartment of Marlene Levenson. Marlene is a member of SAAGA — Survivors Allied Against Government Abuse. Her aunt was experimented on at the Allan Memorial in the late 1940s. A week before our meeting, Marlene was firing up a crowd at a rally in Ottawa.

Marlene (from the rally): Why am I here? Because I want justice!

Ben: But today, she’s hosting a small group of other SAAGA members, who are eager to share their own stories with us.

Marlene: (setting up snacks) Help yourself, now, then, or later.

Amory: The first to arrive is one of the group’s organizers, Julie Tanny. She’s the lead plaintiff in a new class-action lawsuit that SAAGA is bringing against the U.S. government, the Canadian government, the Allan Memorial Institute, and McGill University.

Ben: But her story starts when she was very young. For Julie and her siblings, weekends were “Dad time.”

Julie Tanny: He was very involved. And when he came home, it was just empty.

(music plays)

Amory: Julie’s father, Charles Tanny, was sent to the Allan in 1957, not for anxiety or depression or some other form of mental illness, but for nerve pain, specifically, something called trigeminal neuralgia.

Julie: … which is a pain in the temple that radiates into the jaw, and his family doctor suggested he see a psychiatrist assuming it was psychosomatic. And the psychiatrist we didn’t know was actually working at the Allan with Cameron. And he put my father into that program.

Ben: That program was Dr. Cameron’s de-patterning and psychic driving regimen.

Julie: And my father was put into psychic driving for 30 days, as well as insulin comas and all the narcotics and drugs that they gave them. And, after 30 days, they expressed concern that my father still had ties to his former life because he was asking to see his wife.

Ben: Which, to Cameron and his team, meant that the so-called “treatment” wasn’t working. They decided to keep trying.

Julie: And after 27 days my father was reduced to a five-year-old wearing diapers. And Dr. Cameron noted that it looked like this is as far as we could take him. And then he was released.

Amory: Julie herself was just 5 years old at the time. She didn’t know where her father had gone, or why. But when he returned 2 months later, he didn’t seem to remember much of anything about his life before the Allan.

Ben: Charles had been a loving, attentive parent. Now he was, at best, detached. And at worst…

Julie: My father came home with a very short fuse and physically violent. All I know is when I read my father’s interview when he got to the Allan, because they used part of the interview to use the tapes that they run 24/7 under your pillow, one of the things he said in his interview was that his youngest daughter was the apple of his eye. Yet when my father came home and I got a little bit older, he started beating me, and not my other two siblings.

Ben: This shift in Julie’s dad is sadly familiar to many members of SAAGA. As one of the group’s organizers, Julie has helped a lot of other family members like herself try to understand the information in their loved one’s medical records. And she’s picked up on some patterns.

Julie: In a lot of the records I’ve read the same thing over and over again that Dr. Cameron found the patient to be aggressive. And, you’d think the man was smart enough to figure out he was making them aggressive. There is such crazy stories of things that happen to families where a father tried to kill them or he had a noose hanging, waiting in the basement or just like crazy, violent, aggressive behavior.

Amory: Another pattern Julie’s noticed is one of silence. Family members who haven’t been able to talk about what happened to their mothers and fathers and siblings, with each other, or anyone else.

Ben: Some of it has to do with the stigma around mental illness, and the shame that can be felt by everyone it touches — a stigma that still exists today, of course, but was even more present in the 50s and 60s.

Amory: We heard this over and over again talking to people.

Marlene Levenson: You weren’t allowed to talk about mental illness. It was like a cancer in the family and no one wanted to know about it.

Angela Bardosh: Just dealing with mental illness and the stigma of mental illness.

Marian Read: You see back then, you’re crazy. Imagine what it was like thinking you had a crazy parent — then everybody’s gonna look at you.

Amory: This pain, for many people, has been the greatest silencer of all.

Julie: There are people who very much want justice, but in some ways because of the government’s stance on all this, which is to ignore it all, they just can’t come forward. And the pain of reliving it all, we have many people in our group who just cannot talk about it. Can’t!

Ben: For Julie, the Canadian government’s silence — has been deafening.

Julie: They have apologized to everybody. They’ve apologized to the indigenous, they apologized to the Inuits, they apologized to the Japanese. They’ve apologized to everybody! I mean, our country has a horrendous history. But, unfortunately, our case, for reasons that we don’t understand, they just can’t acknowledge.

Amory: So Julie and the other 300-plus members of SAAGA want their apology from the Canadian government, and from everyone who played a role in aiding and allowing Dr. Ewen Cameron’s brainwashing experiments to take place without the consent of his patients. They filed their class-action lawsuit in January of 2019. Where does it stand today?

Ben: It doesn’t. A class-action suit needs to be authorized by a judge before it can move forward. And, more than a year later, that hasn’t happened yet.

Amory: In part, because it took SAAGA’s attorneys months just to serve the CIA. And now, the U.S. government is trying to have the whole case dismissed, claiming immunity against a suit filed in an ally’s jurisdiction.

Jeff Orenstein: Obviously, we don’t agree.

Amory: This is Jeff Orenstein of the Consumer Law Group. He’s representing the SAAGA plaintiffs in their class-action suit, and he says that — despite the challenges — the decision to include the U.S. government in their litigation was a no-brainer.

Jeff: The way I always have been taught to do things is you go after everyone who you think is responsible. And so it was really not a question for me of leaving out a party that I think was involved in this.

Ben: What was a question is what justice actually looks like for families that suffered government-sponsored harm. Jeff’s colleague on the case, Andrea Grass, says it includes something that the plaintiffs in Orlikow vs. United States never got: an apology.

Andrea Grass: So what we’re talking about with an apology is accountability. And no one seems to want to take accountability for this.

Amory: Andrea and Jeff are also seeking a, perhaps less poetic, but more practical form of justice for their clients: compensation. They’re hoping they can do a lot better than the $100,000 Jim Turner got for his clients in the 80s, but they’re bracing themselves for a similarly long fight.

Ben: But just a couple miles away from where Jeff and Andrea are working on their class-action suit, not far from the Allan Memorial itself, another Montreal lawyer is taking a different approach.

Alan Stein: Let’s see, where do you want to interview me? That’s the thing.

Ben: Alan Stein greets us at reception, and he seems excited to have us and to tell his colleagues.

Alan: They’ve come all the way from Boston to interview me. How do you like that?

Amory: Alan’s office is a trove of information. Boxes of case files and court documents stacked up against the walls, and a desk piled high with papers.

Ben: This looks exactly like I would imagine a lawyer’s desk to look.

Amory: Within his stack of papers are documents for a suit representing about 60 families whose loved ones were experimented on by Dr. Cameron.

Amory: This is hundreds of pages.

Alan: Hundreds of pages!

Ben: Alan’s suit is a direct-action case, which — unlike the class-action — does not require the authorization of a judge before it can move ahead. He’s suing the Canadian Government, the Allan Memorial, and McGill University — but not the U.S. government.

Alan: I decided not to sue the CIA.

Amory: Why?

Alan: Because I felt it would delay the action indefinitely. Most of my clients want to at least have a hearing within the next few years. A class action like this where you sue the CIA, you could be tied up in court for 10, 15 years!

Ben: Alan doesn’t expect his suit to take that long. But it’s still a slow process. And given the global pandemic, things are currently at a standstill.

Amory: Whenever they get going again, Alan’s asking for $850,000 in damages per family. Although really, he’s hoping to settle.

Alan: Because it’s a very time consuming thing, it’s very difficult for these people to have to resumé what they went through, how they suffered without a mother, father, sister and brother.

Ben: Alan also hopes a settlement would come with an apology, but it’s not the priority. Whichever lawsuit we’re talking about here, direct action or class action, it’s difficult for victims to imagine what healing really looks like. Here’s Julie Tanny again.

Ben: What is going to make it better?

Julie: Nothing. Nothing will ever make it better. But for me and a lot of other people who suffered real financial hardships as a result of it, the compensation will definitely help. Is an apology gonna be enough? No, these aren’t the guys who did it. But these are the men who are still working very hard to cover it up. And you have to wonder why. This isn’t even in our history books. It’s crazy!

Amory: We’ve reached out to the Canadian government, the CIA, and the Allan Memorial Institute via McGill University and the Royal Victoria Hospital. The Canadian government never responded. The CIA said they wouldn’t make someone available to talk to us. And the Allan Memorial Institute sent a response that reflects just how confusing the relationship between the Allan, McGill, and the Royal Victoria Hospital is.

Ben: The Allan Memorial Institute is the psychiatric wing of the Royal Victoria Hospital, and the Royal Victoria Hospital is one of McGill’s teaching hospitals.

Amory: And these degrees of separation have probably made it easier for all of them to pass the buck on what happened at the Allan under Cameron’s leadership. Their statement to us reads:

The McGill University Health Centre acknowledges that Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron carried out experiments at the Allan Memorial Institute during the 50s and 60s. The research attributed to him continues to be controversial, and its consequences, unfortunate. The courts have already established that the Royal Victoria Hospital was not considered, by law, the employer of Dr. Cameron; at the time, he exercised his profession in an autonomous and independent manner.

Julie: I guess they just want us all to die off and then the next generation is not going to bother fighting for justice. So maybe it’ll just go away. But, I don’t know.

(music plays)

Ben: About a year after winning a settlement for their clients in Orlikow vs. United States, Jim Turner and Joseph Rauh published a paper entitled “Anatomy of a Public Interest Case Against the CIA.” In it, they detailed the government’s attempt to quote “ignore the plight of its victims,” and insisted that the importance of curbing that kind of arrogance could not be overstated.

Amory: The takeaway from that case for Val Orlikow — the Canadian grandmother who dared to take on the CIA — and for anyone who would hopefully follow in her footsteps, is that there is power in the very pursuit of justice. In the pursuit of not being ignored. No matter how loudly and how long you have to holler for it.

Jim: I think it’s gonna be a hard row to hoe. That being said, again, I applaud any attorneys and any families who are still seeking justice for what happened at the Allan.

Amory: Any words of advice for those attorneys?

Jim: Don’t give up.

(music plays)

Ben: Do you think your grandmother would be proud to know that people haven’t given up on trying to do that and hold the CIA accountable?

Sarah: Absolutely. Yes. Everybody deserves their day in court.

(music plays)

Amory: However long it takes the members of SAAGA to get their day in court, there is someone who will never be able to answer to them, someone who will never be held accountable for the experiments at the Allan, and who will never apologize to these former patients and family members: Dr. Ewen Cameron. Shortly after he left the Allan Memorial Institute in 1964, Dr. Cameron suddenly… died.

Duncan Cameron: We all very much wished that my father was alive because he would have had to deal with that issue and would have dealt with it quite effectively.

Ben: Next time, in the fifth and final part of “Madness,” the collapse of Dr. Ewen Cameron…

John Marks: And they found his work next to worthless.

Amory: … and the chilling legacy he left behind.

Stephen Bennett: You can’t separate Guantanamo. This is the legacy.