South Dakota’s new secretary of state has ties to vocal Minnesota election denier

Secretary of State-Elect Monae Johnson campaigned as the candidate who would secure South Dakota’s elections.

That message helped her defeat Democratic challenger Tom Cool – who campaigned on concerns about Johnson being an “election denier” – with 65% of the vote.

She’s one of very few election deniers to win statewide office during the mid-term election, and she did it with the help of a prominent Minnesota election conspiracy theorist, Rick Weible. The former small-town Minnesota mayor has been a key figure in spreading election conspiracies around Minnesota since 2020.

Johnson has declined to say if she subscribes to the conspiracy theory that the 2020 election was stolen but her proposals for election law changes in South Dakota align with those of right-wing election deniers. Changes such as an audit of every precinct in South Dakota and a state-level push to convince county auditors to hand-count all ballots. She also suggests lawmakers consider barring the use of tabulator machines altogether.

Election officials across the state — including the outgoing secretary of state and a county auditor who presided over the last fully hand-counted election nearly two decades ago — worry that such changes would complicate counting and render it less accurate.

“You’d never get an accurate count,” said Julie Pearson, the former Pennington County auditor who oversaw the transition from hand-counted ballots to tabulation. “Plus, the time. Our scanners, I think, run 200 ballots a minute.”

Johnson comes to office with election credentials of her own. She spent more than eight years working in the office she’ll take over in January. She said her experience in the secretary of state’s office showed her the value of customer service. Her predecessor, Steve Barnett, excelled in that regard, Johnson said, but she also said there are important differences.

“The main difference is I’m totally against voter fraud, online voting, or online voter registration and updates, and that secretary of state (Barnett) was pushing it his whole four years,” Johnson said. “His latest bill was that if you were already in the system, you could go online and update your address to make it more convenient.”

Barnett said voters can’t change any of their voting information through the state’s online system. The bill he proposed that would have made that possible, which did not pass, would have required a valid state identification and Social Security card to make any change.

Machine mistrust

Barnett has publicly rejected tabulator-related concerns of voter fraud. But Johnson said her concerns about voting tabulator machines and online voter updates are shared by “highly qualified professionals.”

“I had people reaching out to me saying ‘no’ because anything can be hacked,” Johnson said. “That was the biggest thing. The people reaching out to me were IT people, military people.”

Johnson did not name the IT and military sources who expressed those concerns, but campaign manager Gretchen Weible did: Chiefly, her husband Rick Weible, a former mayor of St. Bonifacius, Minnesota, who traveled Minnesota prior to the midterms and posted videos claiming election fraud and pushing for changes to election procedures, hardware, and software. The Weibles were on stage with Johnson during her election night victory speech in downtown Sioux Falls.

Rick Weible said his time as mayor exposed him to the flaws of machine counts, which led him to the election integrity fray.

“It was off by one to two votes every election,” Weible said.

However, Weible said tabulators proved valuable in post-election audits.

The Johnson campaign also pointed to Jessia Pollema of South Dakota Canvassing — an organization that advocates against electronic devices in South Dakota elections.

The crowd pushing election integrity has a misunderstanding of what “the machines” in question are and do, Barnett said.

“These people think anything that can be plugged into a wall can be hacked, whether it has a modem or not,” he said.

The state already uses paper ballots and requires voter ID, but Johnson said there is room for improvement. Specifically, she would like to implement a post-election review. All but five states have some sort of post-vote audit, and those audits can look very different from state to state.

A March story in the Reformer about an election reform rally that featured Rick Weible noted that 3% of precincts in that state perform hand counts after each election. Those counts are observed by representatives from both parties.

The 400,000-ballot audit of the 2020 election in Minnesota confirmed the validity of the state’s machine-run results.

Secretary-elect Johnson would like to see auditors in each county take a sample of the ballots from each precinct and hand count them to make sure the votes line up with tabulator machine counts.

“And if the hand count matches, your precinct is good to go,” Johnson said.

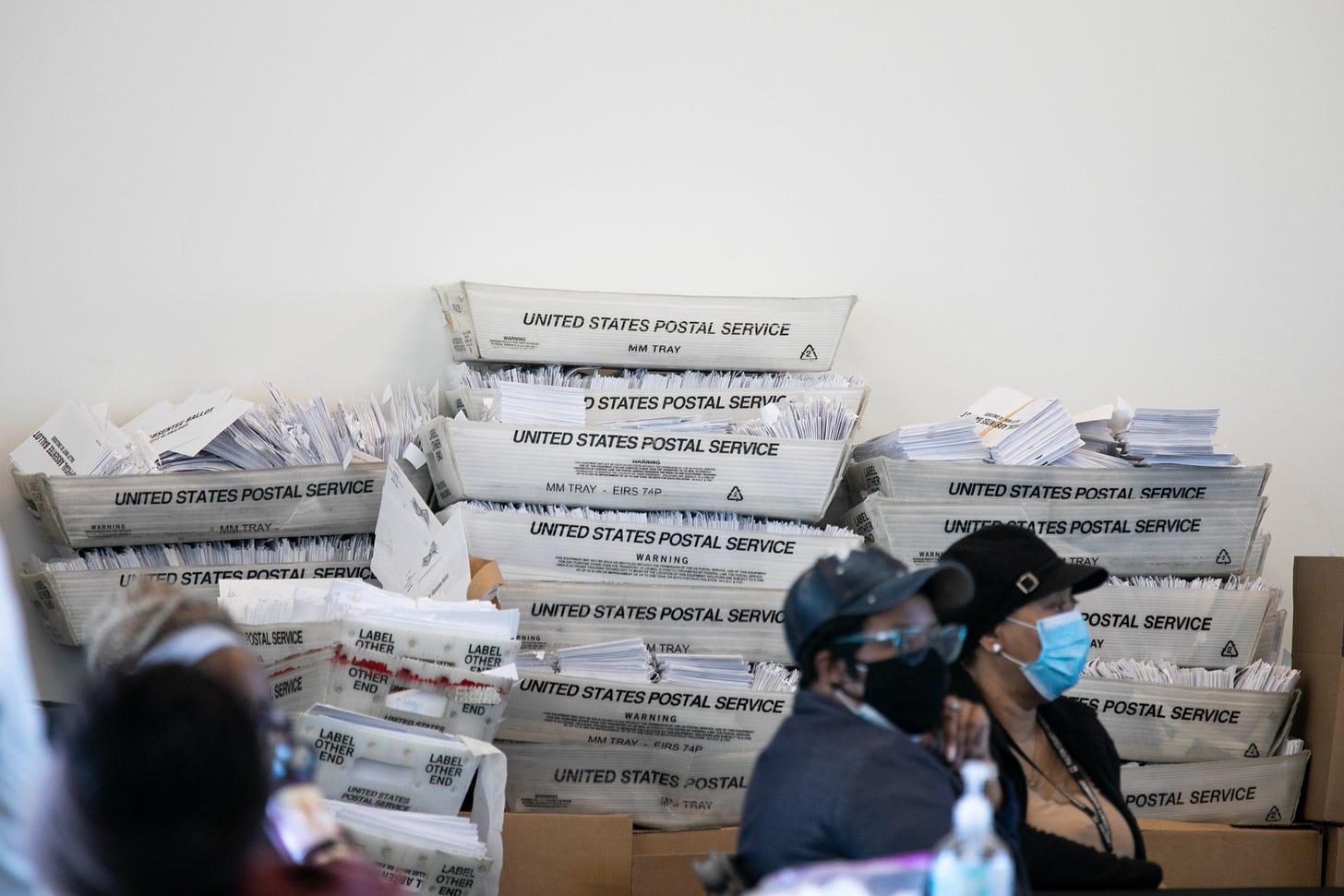

Hand-counting ballots

County auditors make the call about tabulator use on the county level, but Johnson said she would advise against their use. It would take legislative action to do away with tabulators altogether.

“I know there’s a lot of people that would love all the machines gone,” Johnson said.

One South Dakota county tried hand-counting ballots on Election Day. Tripp County gave it a go during the recent midterms – the only South Dakota county in nearly 20 years to perform one.

Several races had to be recounted by Tripp County’s volunteer counting boards — sometimes three or four times — on election night. Seventy-five ballots even went “missing” in one precinct during the post-election audit.

Ironically, the explanation for the mismatch was identified by a voting tabulator — the machines Johnson and Tripp County commissioners dislike.

“It’s been a nightmare,” Tripp County Auditor Barb Desersa told South Dakota Searchlight the day after the election. “To me, it’s plain as day (that the machine is more accurate), but I know there are others that don’t see it that way and question it.”

Johnson advisor Rick Weible said the issue in Tripp County wasn’t hand-counting ballots, but that the people counting those ballots grew tired. A fine-tuned process for hand counts would alleviate fatigue-related problems, he said.

“The way we’re doing it in South Dakota is terrible,” Weible said. “We need multiple shifts.”

For larger counties like Pennington, where nearly 46,000 ballots were cast for the 2022 general election, counting by hand isn’t realistic, Auditor Cindy Mohler said.

Mohler expects election integrity legislation will be introduced during the upcoming legislative session, but she hopes legislators reach out and listen to officials like her.

“Please talk to your county auditors, They’re the ones in the trenches, dealing with this every day. The laws will affect the work they do,” Mohler said.

Minnehaha County Auditor Ben Kyte echoed Mohler’s concerns about moving away from tabulators.

“It would create some challenges,” Kyte said. “We had over 75,000 ballots cast. I would be concerned about the accuracy of hand counting.”

Rick Weible said larger counties are divided into precincts, making hand counts feasible.

Auditor with hand-counting experience trusts tabulators

Former Pennington County Auditor Julie Pearson oversaw that county’s transition from hand-counted ballots to tabulator counts in 2004.

“(I) guarantee you 99.9% of the time your machine count is more accurate than a hand count is ever going to be,” Pearson said. “They’re gonna lose track of where they’re at. And when all you’re doing is doing little sticks (to keep count), you know, one two, three four five, how do you not lose track of where you’re at?”

The current system in South Dakota already offers a pre-election audit, she said. Prior to an election, a foot-tall deck of filled-out sample ballots is run through the tabulators, Pearson said.

“And then on election night, we’re required to run the test deck through each machine,” Pearson said. “And our machines are secure. The auditor’s office is always locked. Nobody is allowed in there. Once we start voting or have ballots, nobody else touches our ballots but deputy auditors and law enforcement.”

Pearson disagrees with Johnson’s policy prescriptions, but she thinks her intentions come from the right place.

“Whether you call her an election denier or not, I think it’s good that any new secretary of state, as the primary election official in the state of South Dakota … review everything that is in that election process,” Pearson said. “That’s really part of their job.”

Johnson said she does not want to make elections and voting harder for people. She’s particularly concerned about voting rights for the state’s Native American population, she said.

“I want to work with the tribes,” Johnson said. “I don’t know if other secretaries of state have reached out to the tribes. So once I am sworn in, that’s one of my main goals.”

Beyond elections

The office of the secretary of state is responsible for state elections and South Dakota’s public documents. That is another area Johnson sees room for improvement.

The state’s campaign finance expenditure reports ought to be more navigable, she said. A searchable database would help reporters “follow the money trail.”

“A lot of reporters reached out to me and said, ‘Is there any way that we could just put in a name like, say Monae Johnson, and then see who Monae donated to right now?’ You can’t do that search right now.”

This story originally appeared in South Dakota Searchlight, a States Newsroom publication and sibling site of the Minnesota Reformer.