The Dangers of Pseudohistorical Conspiracy Theories

Introduction

In November 2022, Netflix released their controversial documentary-style series entitled Ancient Apocalypse. It featured the musings of Graham Hancock, a speculative historian, and his attempts to prove the existence of an Atlantean society which he claims kickstarted the development of ice-age civilisation before it was destroyed in a mysterious cataclysm. Hancock has appeared multiple times on the Joe Rogan Experience, a podcast which has previously platformed harmful narratives about COVID-19 and faced harsh criticism over episodes featuring notorious conspiracist Alex Jones. Following immediate condemnation by archaeological and historical groups, Ancient Apocalypse was dubbed “the most dangerous show on Netflix”.

Like true crime discussions, online discourse over the mysterious and unknown history of humankind has become something of a pop-culture phenomenon, complete with sub-communities, like Hancock’s own website forum, and dedicated content creators. More concerning than harmless interest and debate, the internet has also facilitated the spread of huge amounts of mis/disinformation and harmful content. Through eroding trust in the actual facts of our world, picking scapegoats and advancing harmful rhetoric, the realm of the pseudohistorical creates real danger and a potential gateway to extremist thinking.

At a time when faith in institutional narratives is dwindling, it is crucial to identify when seemingly innocuous discussions have been infiltrated by dangerous ideologies. In this Insight, I will demonstrate how popular pseudohistorical trends and narratives are supported by underlying supremacist and violently conspiratorial ideas, and how such content can help filter these positions through the lens of popular conspiracy theories. Using the examples of Tartaria, ostensibly benign and popular on platforms like TikTok and Reddit, and the more certifiably extremist-aligned Hyperborean narrative, we can uncover the extreme threads woven throughout pseudohistorical tales.

Conspiracy Theories on Social Media

Pseudohistory refers to the kinds of unsubstantiated and baseless claims that are made in Hancock’s Netflix programme; narratives that claim to be recounting historical fact, but without reference to the standards of proof or methods of history as a discipline. Topics like Holocaust denial and the Vinland myth, in which North America was settled by Vikings, are covered by the pseudohistorical category but the possibilities are really as broad as history itself. Given the cryptic nature of these theories, the pseudohistorical narrative straddles or embraces conspiracy, and the two can become indistinguishable in online spaces.

Given the recent visibility of conspiracy theories on topics like the pandemic or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, attention has been paid to the potentially harmful effects of this kind of thinking. The issue is amplified by the internet, with platforms presenting unmitigated misinformation to users who are already algorithmically enticed into bias-confirming echo chambers.

Perhaps the best illustration of this is QAnon, a theory suggesting Donald Trump is leading a military-intelligence program to save America from a cabal of sex-trafficking paedophiles and international and domestic enemies. The theory, which asked believers to question everything, including history, and to reject the account of the past taught to them by the so-called ‘fake news media’, was a major force behind the January 6th insurrection, and otherwise crossed into the real world by inspiring a number of criminal acts. Pseudohistorical trends can harbour the same kinds of rhetoric as dangerous conspiracy theories by constructing core myths that extreme groups can use to support their narratives and form identities around.

Tartaria

Dubbed “the QAnon of architecture”, the pseudohistorical ‘nation’ of Tartaria has developed a cult following on social media. Supposedly, this country was a grand and culturally-rich empire, found in the area today recognised as Central Asia and parts of Europe. More fantastical strands of the theory add suggestions of Tartaria’s advanced technology, Tartarian buildings buried under modern cities as far as North America, or its population of giants.

Believers seek ‘evidence’ for its existence in seemingly mismatched architecture found across Europe and Asia, as well as references to ‘Tartary’ or ‘Tartaria’ on historical maps. Historians have since explained this to be a name given to various regional ethnic groups by outsiders. The theory concludes with the view that modern European powers conspired to cover up Tartaria, which was destroyed in a mud flood, and replace the idyllic civilisation with a globalised, degenerated society that they could control.

Figure 1 – Users of the Graham Hancock forums discussing Tartaria

On TikTok, the #tartaria tag has amassed almost 300 million views, and the associated #mudflood, the supposed reason for the empire’s disappearance, a further 150 million. In many cases, Tartarian interest groups present themselves as inquisitive and free-thinking, like other conspiracy theorists. The sidebar description of Reddit’s /r/Tartaria 23,000-strong community suggests “Maybe the History we’ve been told is a lie!” This content easily seeps, through algorithmic recommendations, into the feeds of users who did not directly seek content on Tartaria, especially when it is presented in a purposefully engaging way. As users search for meaning and identity in a radically-changing world, conspiracy theories provide both a welcoming in-group as well as a method of explaining the chaos through cohesive narratives, complete with heroes and villains.

Conspiratorial content presenting falsities like Tartaria as fact is designed to drive engagement. Slideshows of the kinds of architecture which supposedly ‘prove’ the existence of Tartaria are edited down into catchy clips that are designed to go viral, featuring explanations of the theory without any context or evidence to back up the claims. Users host their own discussions, use their own ‘facts’ and reach their own conclusions, constructing their own version of history and, by extension, reality. Despite appearing benign and attractive to curious viewers on the one hand, pseudohistories like Tartaria further attract the support of ethnonationalist groups who can deploy a useful myth, complete with advanced ancestors and impure enemies, to justify and support claims to supremacy and the resurrection of an idealised ‘culture’.

The Danger of Pseudohistory

The impacts of the anti-vax movement and the visibility of pseudoscientific views during the COVID-19 pandemic have drawn attention to the very real public health implications of conspiracy theories gaining traction online. We should view the threat of pseudohistory in a similar light. The spread of false histories has major implications for trust in governments and international institutions like the UN, as well as the narratives they produce, can motivate crimes by believers in white genocide or ‘Great Replacement’ narratives, and unknowingly promote extremist perspectives.

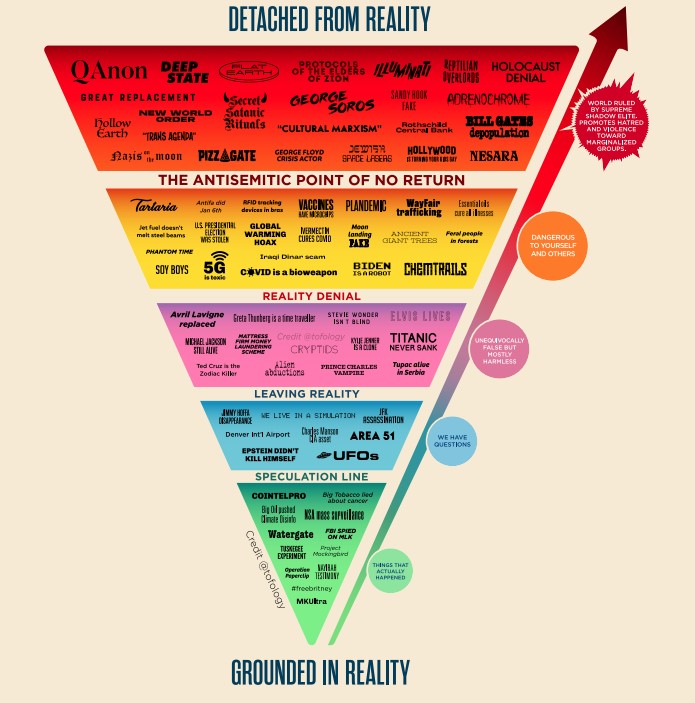

Tartaria, as harmless as it may seem, has been used by Russian ethnonationalists to support an expansion of Russian land and the supposed ‘supremacy’ of Russians. Pseudohistory has been historically deployed by extremists to justify reclaiming certain areas and expelling others, oftentimes accompanied by suggestions of ethnic or racial ‘purity’. On the Conspiracy Chart created by extremism researcher and TikToker Abbie Richards, Tartaria inhabits the second-most harmful ‘Reality Denial’ segment, described as a theory “dangerous to yourself and others”. In addition, the conclusion of Tartaria being hidden from us evokes parallels to the ‘Great Reset’ conspiracy theory, which itself suggests that global actors will group up to enslave humanity through vaccines, government control and population control – just as Tartaria was supposedly destroyed and erased to better control citizens through concealing their past.

Figure 2 – Abbie Richards’ ‘Conspiracy Chart’

This is connected to ‘doomer’ content which promotes a nihilistic worldview – in this case, that an insurmountable collaboration between global enemies is holding humankind back from embracing the superior and advanced lifestyle of the Tartarians. These strands of Tartaria content foster an atmosphere of white victimhood and New World Order narratives which portray nations, elites and minority groups such as Jews as the enemy, mirroring other conspiracies that promote a violent distrust in international governments and a desire to oppose modern liberal democracy.

Hyperborea and the ‘Normiefication’ of Extremism

Hyperborea, also known as Thule, refers to a mythical, paradisiacal region of the North Pole. Every believer’s description of the land is different, but each provides some sense of the supernatural, with white supremacist retellings focusing on Hyperborea as a pure, utopian Aryan homeland and forming an origin myth for the white race. Modern Hyperborea content is the successor of Esoteric Nazism, which sought to use close-kept and cryptic knowledge to advance the project of National Socialism in the 1920 and 1930s through officially-sanctioned myth-seeking think tanks like the Thule Society and Ahnenerbe.

Parallels can be made with Hyperborea, the Great Replacement theory and far-right misogynist narratives. Memes found on 4chan compare ‘Chad’ Hyperboreans with racist caricatures of ‘virgin’ non-white people. Hyperborean women are depicted as subservient to men, and the objects of deserving males in an incel-adjacent racial fantasy. The theory is also associated with the Sonnenrad or Black Sun symbol, used by original esoteric Nazis and maintained by violent neo-Nazis, because of its recurring use in propaganda supporting mystical aspects of Nazism and an idealised Aryan ancestry.

Figure 3 – a 4chan user discusses Hyperborea as the real ‘holy land’ of ‘Aryan people’

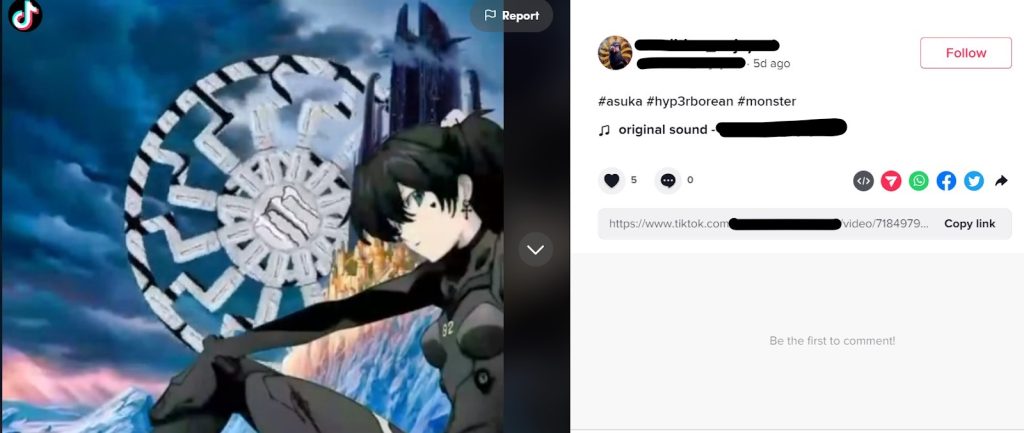

Today’s Hyperborean content, largely made up of trendy videos and digestible memes, purposefully recreates these images of an idealised Aryan race – tall, blond, muscular and white – living in a hidden civilisation immune to the ‘corruption’ of modern society. The content is flashy, well-edited and, most importantly, in line with the cultural and social cues of its target audience. It adopts aesthetic styles like ‘fashwave’ that create a sense of awe in curious users and convey the mystical supremacy associated with the mythical land. These ideas can be powerful to impressionable young people seeking an identity and meaning provided by narratives of ancient mystical homelands. Hyperborean content makes use of cultural cues from gaming communities and anime to further impart its message through ‘edgy’ humour.

Figure 4 – Examples of Hyperborea content using anime characters, from TikTok and 4chan

Making use of subcultural references to anime, among others, can serve to draw impressionable young internet users towards Hyperborean content and beliefs when it appears in these communities online, through compelling aesthetics that provide meaning, identity and a transcendental sense of belonging, as well as offering an epic tale of fantastical lands which teaches them of supremacy. This occurs precisely as tech-savvy teens feel increasingly disconnected from societal and political life; they seek alternative explanations and outlets for the anxieties of the modern world through mediums like gaming and forums which can indoctrinate impressionable viewers into dangerous worldviews that seem to offer them a like-minded community. This adoption of memes and pop-culture references to adapt Esoteric Nazi views to teenage audiences and attract belief demonstrates how online extremists can use the mysterious and engaging draw of pseudohistory as narrative support for violent ideologies.

This process of transferring content designed for chan users to a wider audience through attractive or humorous visuals (dubbed ‘normiefication’) can go some ways to explaining how extremists have been able to infiltrate social media with content that supports their ideology through falsified historical accounts. The application of pseudohistory towards extreme ends is not unique to North America or Europe; Hindutva nationalists in India have fantasised of their own Hyperborean origin myth, with imagined Aryan ancestors from the North Pole supposedly bestowing upon them a supernatural purity. In this case, too, social media groups and messaging apps become a breeding ground for disseminating narratives that support their goals and constructed identity.

Conclusion

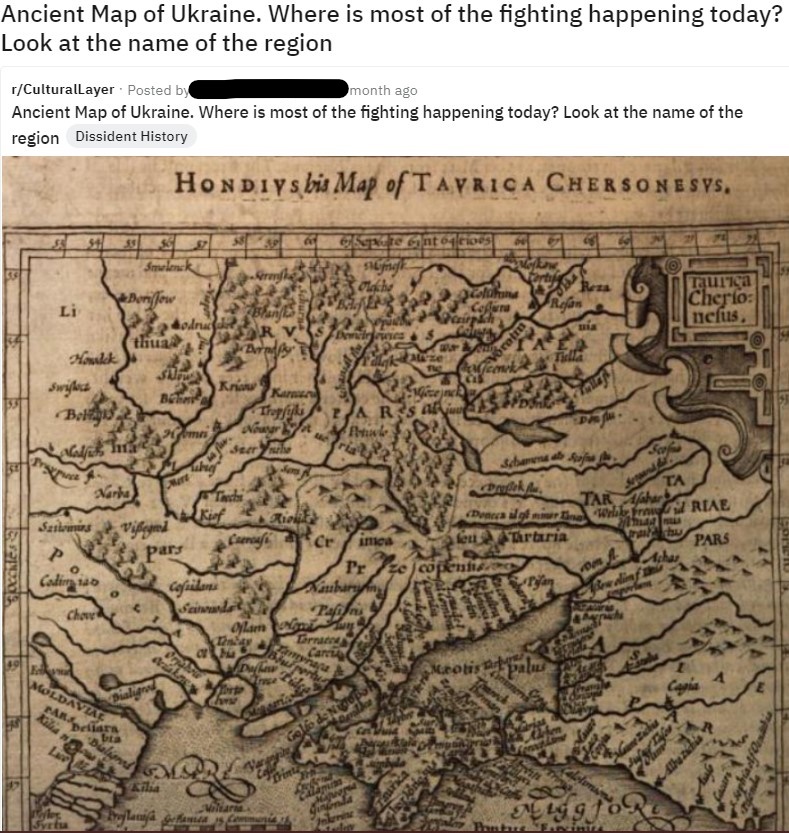

A misinformed understanding of history can lead to not just factually incorrect but harmful perspectives on the present; contemporary issues such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been re-framed via Tartaria-related content to imply that Russia is reclaiming Tartarian land.

Figure 5 – Reddit post discussing the Tartarian causes of the invasion of Ukraine

As the anti-vax and QAnon cases have displayed, dealing with disinformation on social media is a global challenge. Signposting on mainstream social media platforms has helped clearly identify misinformation, but in minimally-moderated discussion boards like 4chan, this is a much more complicated matter. Counter-speech has also been used by some content creators seeking to undermine the virality of these theories. Those with expert knowledge can take the initiative to comprehensively break down pseudohistorical narratives and expose the faults of arguments made about the history of societies and civilisations, for example, on Hancock’s Netflix programme. While these shows, like Tartaria, do not explicitly promote extremist views, they can both support and be supported by extremist ways of thinking.

Racialised pseudohistorical perspectives that are presented as fact allow for far-right extremist and white supremacist ideas to infiltrate digital communities and mainstream online discourse. Social media is weaponised to spread a false history and thus imply a fundamentally different identity and a story of modern society in which white people are simultaneously victims and victorious. Those driving this discourse know their audience and craft messages with engagement in mind, using modern editing tools and meme formats to draw users in during the ongoing ‘infodemic’.

History is an ever-changing field; we are constantly re-evaluating the past with fresh perspectives and changing our outlook as new evidence comes to light. To keep in step with individuals seeking to bend the historical fact to their own will, it is vital that we both recognise and formulate responses to the rising popularity of pseudohistory and its potential to harbour extreme perspectives.

Harrison Pates is a recent graduate from the University of Birmingham, with a Master’s in International Security in Terrorism. Twitter: @HarrisonPates