The 15-Minute Conspiracy

As cities worldwide emerge from the social and economic devastation wrought by the coronavirus pandemic, urban planners have discovered a newfound enthusiasm for localized and pedestrianized urban life. In recent months, however, the concept of the “15-minute city” has become the center of a new and convoluted online conspiracy theory. The reactionary backlash to the 15-minute city exemplifies the amorphous fusion of conspiracies that has come to characterize anti-government sentiment in the internet age. One outrage bleeds into the next, shifts in rhetoric gloss over a fundamentally similar narrative of grievance and sinister elites, and conspiracists expand their ranks to include a new class of radicalized believers. The heightened anxiety of the pandemic prompted an additional surge of interest in alternative, and extreme, ways of making sense of the world; now, several years into the post-pandemic reality, the lockdowns of early 2020 remain a cultural touchstone against which the far right can rally. Recent protests against limited-traffic neighborhoods in Oxford exemplify this lingering and exploitable anti-government anger, which has failed to dissipate even after the loosening of Covid-19 restrictions.

About a decade ago, the social scientist and Sorbonne professor Carlos Moreno developed an urban planning concept he called the “15-minute city.” Taking its cues from the community-focused urban development pioneered by Jane Jacobs in the 1960s, modern proponents of new urbanism and walkable cities, and even as far back as the satellite “garden cities” of the early 1900s, the 15-minute city describes an urban plan in which most daily necessities can be accessed via a 15-minute walk or bike ride to another point in the city. It has taken root in academic circles, and many variations have grown from Moreno’s original plan.

Advocates tout the 15-minute city as a climate-friendly return to local living, and many cities worldwide have adopted the model as a goal. The concept reached the popular consciousness when Mayor Anne Hidalgo of Paris included achieving something close to the 15-minute city as a long-term goal in her 2020 reelection campaign (Moreno is one of Hidalgo’s advisors). Following the example set by Hidalgo, a notable climate progressive, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group set “creating ‘15-minute cities’” as a central health and wellbeing aim in their Covid-19 Recovery Task Force report. The people-first urban planning concept has also reached communities beyond the international metropolises represented by the C40 group; just recently, O’Fallon, Illinois, a community of 32,000 residents outside of St. Louis, implemented it as a framing goal of its post-pandemic community development plan.

Far from being controversial, one would assume that accessing the essentials of daily life within one convenient radius would appeal to the ordinary citizen. Likewise, the enthusiasm among urban planners in communities big and small for adopting the concept would seem to indicate that the 15-minute city is in fact the city of the future. However, as recent protests against new urban infrastructure in Oxford demonstrate, even an idea as seemingly benign as the 15-minute city can rapidly become the center of sprawling conspiracy and outrage.

In 2022, the Oxfordshire County Council began to implement an expansion of low-traffic neighborhoods (LTNs) in the eastern part of the city of Oxford. LTNs generally include limiting the number of cars, as well as regulating vehicle speed, on roads in order to expand pedestrian and bicycle accessibility. LTNs aim to increase alternative modes of transit and reduce collisions and carbon emissions; in short, they exemplify climate-conscious urban planning. Efforts toward LTNs are increasingly common in the UK and Oxford’s plan to implement traffic filters followed a standard pattern for British cities.

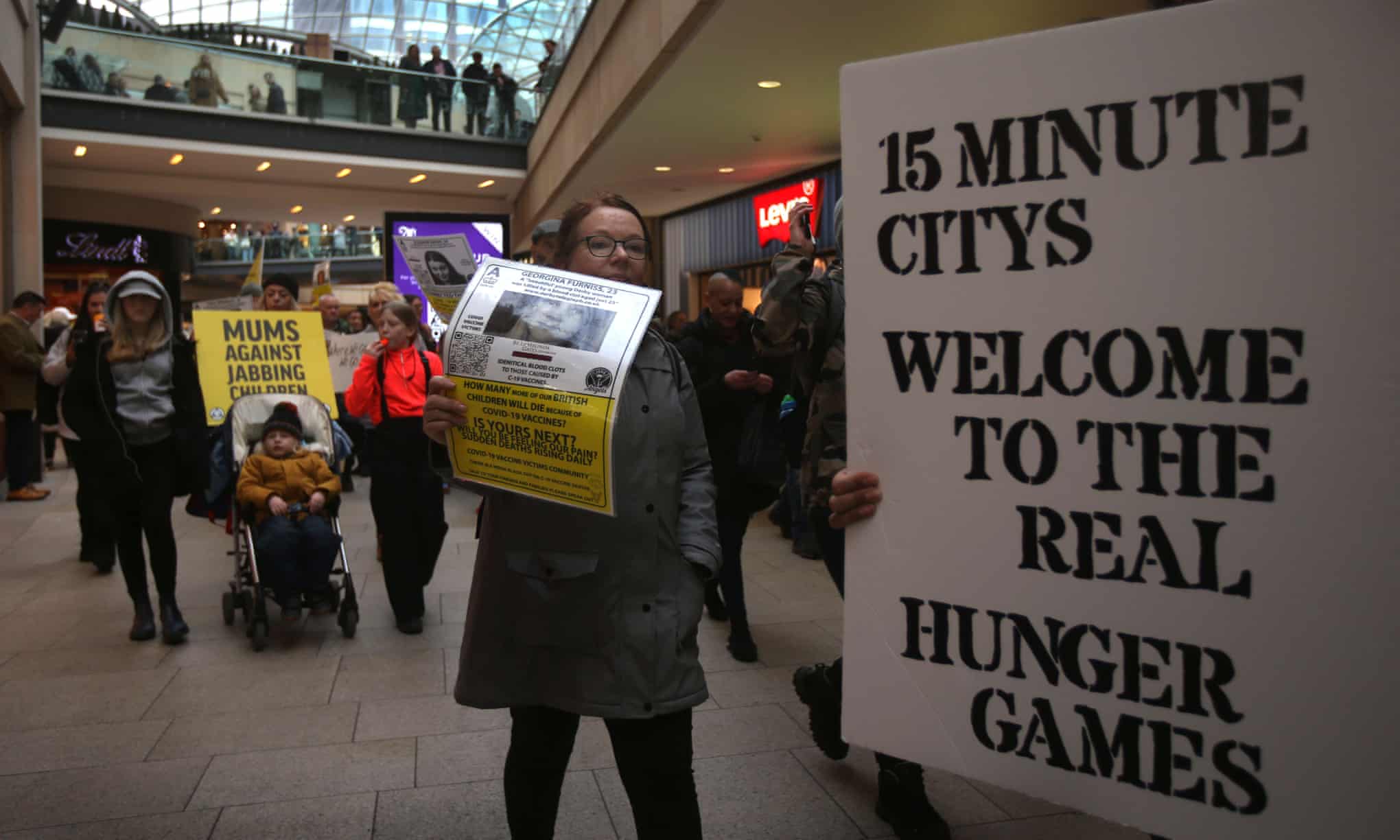

But on February 18, over 2,000 conspiracy-fueled demonstrators congregated at a protest in Oxford, demanding a halt to LTN infrastructure. The conspiracy against new urbanism follows a predictable pattern: Shadowy elites (here, “socialist” city councilmembers) impose a restrictive world order on an aggrieved group of ordinary citizens. The protestors’ online rhetoric derided the 15-minute city in particular as an example of leftist “ghettoization,” in spite of the fact that Oxford’s plan did not include reference to the concept. The experience of the pandemic seemingly constitutes a critical origin point for such outbreaks of aggressive anti-government protest, even those concerning apparently unrelated matters; many Oxford protest signs linked pedestrian-friendly urban infrastructure to the Covid-19 lockdowns of years prior, weaving a continuous narrative of tyrannical state surveillance and enforced confinement from disparate policies.

The Oxford protests also demonstrate the increasingly pervasive influence of American conservative rhetoric in particular. The conspiracy reveres the car-friendly city, but Oxford’s medieval town center has always been pedestrian- and bike-accessible and, if anything, difficult to navigate via automobile. And, most alarmingly, they exemplify modern far-right conspiracy theories’ ability to fuse at will, expanding their numbers with each new source of grievance. Some marchers at the February 18 protest reportedly chanted “Jews will not replace us,” an antisemitic rallying cry frequently leveled by white supremacists.

The backlash that arose in Oxford took on even further significance when conversations about the 15-minute city reached Westminster, England in late February. Nick Fletcher, a Conservative MP from South Yorkshire, demanded parliamentary debate, describing the idea as an “international socialist concept” threatening the integrity of British cities. A conservative presenter on GB News claimed that developments like the ones in Oxford heralded “a surveillance culture that would make Pyongyang envious,” drawing a direct line between pedestrianizing cities and authoritarianism and exposing a whole new audience to the conspiratorial line of criticism. “The latest stage in the ‘15-minute city’ agenda is to place electronic gates on key roads in and out of the city, confining residents to their own neighborhoods,” claimed one sensationalist headline.

This extreme and bizarre conspiracy theory, stemming from as anodyne a concept as a localized city, marks a significant merging of various threads of far-right radicalism that have been percolating in the United States and Europe. Further, the demonstrations in Oxford represent the fascinating injection of car-centric American notions of freedom into the vocabulary of European ideologues. In all, the 15-minute city conspiracy encapsulates the increasing attractiveness of extremism in the information-saturated post-Covid world, where the scores of citizens disaffected by lockdowns and vaccination requirements have instant access to infinite fodder for their paranoias.