Why 2024 Is Shaping Up To Be The Most Online Election Ever

Why 2024 Is Shaping Up To Be The Most Online Election Ever

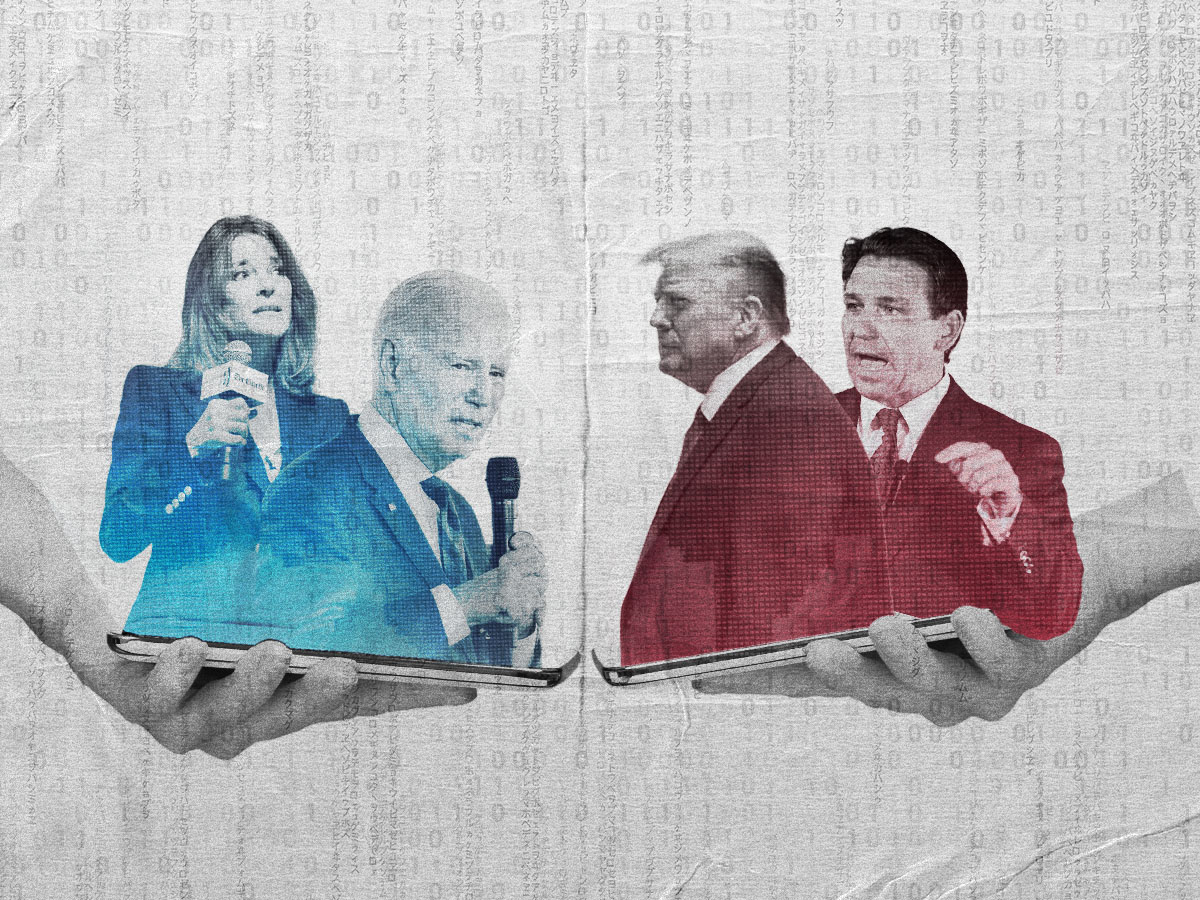

ABC News photo illustration / Getty Images; Reuters; AP Photo

When President Biden’s campaign began flogging “Dark Brandon” merch on its website, my spidey sense started tingling. The sensation rose when a PAC backing former President Donald Trump released an ad mocking Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s “pudding fingers.” By the time DeSantis announced he would be kicking off his campaign on Twitter Spaces with the help of Twitter owner Elon Musk, it was undeniable: 2024 is shaping up to be the most online election we’ve ever seen.

If these references to pudding fingers and glowing-eyed Biden memes bemuse you, congratulations. You probably don’t spend nearly as much time rooting around in the sewers of the internet as I do. But chances are, you’ve noticed at least some of these hyper-online political moments — 2024 candidates are banking on it. And while campaigns have had an online component for decades now, I’m not simply talking about candidates having a social media presence or a website of questionable design. We’re in a moment of transition, one in which candidates increasingly feel pressured to engage with and respond to every Twitter debate, TikTok microtrend and obscure meme in order to feel relevant, but also one in which most candidates didn’t grow up as digital natives. The result is a dizzying cascade of online content and IRL<a class="espn-footnote-link" data-footnote-id="1" href="https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/2024-presidential-elections-online-memes/#fn-1" data-footnote-content="

This stands for “in real life,” for any readers who actually spend most of their time there instead of online.

“>1 references to it that is as likely to make voters cringe as to delight them. And there are still 17 months until Election Day.

Sometimes, the onlineness of the campaign manifests in fairly straightforward ways: Marianne Williamson, who is running against Biden in the Democratic primary, is trendy on TikTok. She also polls better among Gen Z and millennials than she does among older generations. These two facts are likely related, though the former did not necessarily cause the latter. Other times, the onlineness emerges in moments that are so deeply entangled in layers of internet culture, they require multiple explanations to unravel, like when a certain segment of liberal Twitter was convinced DeSantis’s campaign’s desire to work on his ability to control his facial expressions before he gets on a debate stage was a direct response to memes of his face. (It sounds straightforward enough, but I haven’t even mentioned the soyboy wojak layer of it.)

But it’s clear campaigns are indulging in the online aspect of this election, and that’s likely to accelerate, according to Ryan Broderick, an internet culture writer who has been covering the election in his newsletter, Garbage Day. In some ways, the pressure for campaigns to engage with internet culture is an inevitability of our increasingly digitally focused lives. But Broderick said it’s also a direct response to Trump, and the integral role online culture played in his election and administration.

“I sort of see this election cycle as a real referendum on the last two, with the big question being, ‘Does the internet impact, and influence, and amplify people that aren’t Trump?’” Broderick said. “I think it’s a huge concern for the Republicans, because since Trump’s victory in 2016, they’ve kind of just devoted all of their energy to acting like Trump on the internet.”

The internet has always been key to Trump’s success. His prolific and often problematic Twitter account was a chaotic platform from which he could communicate with his supporters with little filter. Entire online communities formed around his ideas and messaging, without Trump ever having to actually interact with them. His false claims that the 2020 election was stolen launched the “Stop the Steal” movement, which organized and grew online before spilling out into the real world, culminating in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Then there’s QAnon: the baseless conspiracy theory that there is a global cabal of Satan-worshiping child sex traffickers and Trump is involved in a righteous plan to bring these evildoers to justice. The conspiracy theory and its community of followers spawned entirely online and was largely based on deciphering social media posts from Trump and those in his orbit, alongside cryptic posts from “Q,” an anonymous message-board user who claimed to have insider knowledge about the government and administration. Trump would wink at the QAnon crowd, while also claiming he knew little about it.

Broderick said this was the secret to Trump’s ability to leverage internet culture: He knows what to post to set the internet ablaze, and how to respond while seeming oblivious to his own impact online. This is in contrast to more obvious, and less successful, attempts to capitalize on internet culture that other politicians have made — consider former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s Snapchat-turned-Vine-meme circa 2015. The then-candidate had attempted to make an irreverent Snapchat post, but it ended up going viral in the wrong way, with Vine (the short, looping video app that predated TikTok) users mocking her.

The difference between a campaign that capitalizes on internet culture successfully and one that just ends up feeling cringy is authenticity, according to Jolie Rosenberg, who worked as a digital organizer for Sen. John Fetterman’s campaign last year. Fetterman’s campaign was widely praised for its effective use of memes and TikTok and for trolling his Republican opponent, celebrity physician Mehmet Oz. Rosenberg said part of the success was due to the fact that the digital teams were large, young and generally given free rein to create the content they liked.

“Largely it was just [saying], ‘If this is funny, if it makes sense, if it fits with the strategy we’re aiming for this week, then we can, I don’t want to say ask questions later, but figure out if we need to pivot later,’” Rosenberg said. “It also makes it a lot less corporate; when a lot of campaigns are trying to focus-group or trying to make sure they suss out every idea and every meme, that removes the authenticity, the primacy and relevance.”

Rosenberg said it also helps to have staff who genuinely support the candidate. Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg proved this during his 2020 presidential campaign, when he attempted to buy online capital by hiring random teen influencers and popular meme pages to post memes and messages about him, which came across as inauthentic and often bizarre.

The 2024 cycle is the culmination of a trend that’s been building throughout the last few elections, but much has changed even since 2022. Trump, despite being reinstated on Twitter, now exclusively posts on his own social media site, Truth Social, which has a significantly smaller reach — Trump has 5.4 million followers on Truth Social, compared with 86.8 million on Twitter. Twitter, meanwhile, has been going through an identity crisis since Musk took over, resulting in many users jumping ship or simply using the platform less. Many right-wing communities that existed on mainstream platforms like Facebook and Reddit have scattered into smaller, disparate corners of the internet on the messaging app Telegram or message boards (in part the result of these communities violating terms of service and being booted off the mainstream sites). And TikTok’s influence on all aspects of online culture continues to grow. This decentralized online ecosystem, combined with the heightened pressure on candidates to engage online, results in the somewhat chaotic stream of memes and internetspeak we’ve seen infiltrating this election. And it means the election is going to keep feeling extremely online as it progresses.

For his part, Broderick predicts this will actually be one of the last elections where the onlineness of campaigns is so palpable. As younger, digital-native candidates age up and start running for office, they will be able to effortlessly engage online without all the hand-wringing and troubleshooting of this generation of politicians. But for now, it’s best to buckle in for the most online election cycle yet — and maybe have your Gen Z cousin on speed dial to explain the memes that fly over your head.