The Banality of Conspiracy Theories

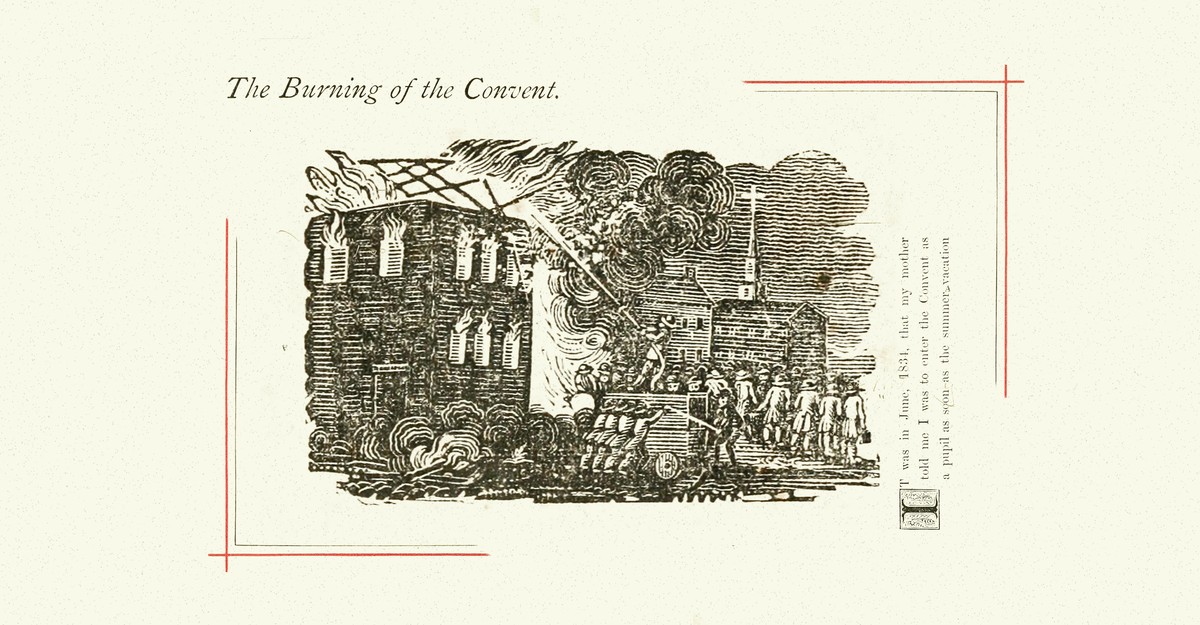

The riot, when it finally happened, was a leisurely one. In the weeks leading up to August 11, 1834, the people of Boston had been openly discussing burning down the Ursuline Convent that stood just outside the city, in what is now Somerville. The convent, many had become convinced, was a den of sexual iniquity, where priests used the confessional as a mixture of blackmail and mind control to exert power over young women and force them into sexual depravity. Further, many in the town had come to believe, infants born of these transgressions were being murdered and buried in the convent’s basement. The only solution was to liberate the women and, calmly, burn the whole place to the ground.

The Ursuline convent was targeted because of conspiracy theories that, in many ways, were the 1830s version of the contemporary panic on the right regarding child sexual abuse: Pizzagate—the conspiracy theory that, in a secret basement under a pizza parlor in Washington, D.C., Hillary Clinton and her circle abused children, drank their blood, and harvested their organs; Operation Underground Railroad—a dubious nonprofit group that alleges a vast network of child sex traffickers; and QAnon—the totalizing conspiracy theory that regularly incorporates accusations of child abuse.

Although it is tempting to see these moral panics as something new, they have been part of American culture for nearly two centuries, and they recur at key moments in history for specific, identifiable reasons. Combatting them requires first understanding that they are not only not novel, but in fact rote—almost to the point of banality.

Conspiracy theories tend to emerge in times of rapid cultural or demographic change; many of them reflect unease with that change, suggesting that it is not just the result of evolving values or newly emergent communities—the messy progression of democracy—but instead the work of a hidden network of nefarious actors whose ultimate goal is the destruction of America itself. And they often portray the American nuclear family, particularly its women and its children, as uniquely vulnerable and in need of protection.

In the late 1820s and ’30s, a sharp increase in immigration, mainly from Ireland and Germany, led to an explosion in anti-Catholic attitudes. Anti-Catholicism itself wasn’t new—it had been fundamental to the founding of American democracy: a model of political participation that wasn’t ruled by a divine authority. Catholics, Protestants feared, could not be trusted to participate in representative democracy, because rather than act as autonomous citizens making informed decisions, they’d vote as a bloc in accordance with the wishes of the pope. (This “philosophical” aspect of anti-Catholicism, which targeted not the individuals so much as the idea that people could be controlled by a religious authority not bound by American sovereignty, helps explain why it was so easily repackaged more recently against Muslim immigrants and the specter of Sharia law.)

“We make war upon no sect,” Senator Sam Houston of Texas said in an 1855 speech at a barbecue for the rabidly anti-immigrant Know Nothing party, while also asserting the need to resist “the political influence of Pope or Priest.” More fundamentally, he wondered, “Are not their doctrines opposed to republican institutions?” One only had to look at Mexico, Houston continued, where “priestcraft rules, and civil liberty is subordinate. There is no freedom where the Catholic Church predominates.” He favored a 21-year naturalization period for immigrants before they could gain the right to vote, which would, he argued, be enough time for them to shed their knee-jerk subservience to foreign religious leaders.

By the mid-19th century, the influx of Catholic immigrants had transformed a rather philosophical question about Catholicism into something more urgent and paranoid. Catholic was now becoming a rumor and a slur. Conspiracy theories proliferated, many framed around the threat of white Protestants being “enslaved” at the hands of the pope. These were a means of preserving a sense of white unity as the question of actual slavery continued to drive apart the country in the decades before the Civil War. Anti-Catholic conspiracists repeatedly used the fear of Catholic mind control to shift the discussion away from America’s divisions. Although white people disagreed on whether or not Black people should be enslaved, they could all agree that none of them wanted that fate for themselves.

A new literary genre emerged. Many popular books—some purported to be memoirs, some pure fiction—involved convents. Scipio de Ricci’s Female Convents: Secrets of Nunneries Disclosed, Richard Baxter’s Jesuit Juggling: Forty Popish Frauds Detected and Disclosed, and dozens of others detailed a nightmare world of women in bondage, lecherous priests, and unwanted infants murdered and buried in cellars.

In these stories and the other sensationalist faux memoirs, the convent was revealed to be not a place of piety and devotion but a secret den of illicit sex and infanticide. George Bourne’s novel Lorette: The History of Louise, Daughter of a Canadian Nun, described the convent as “the sepulchre of goodness, and the castle of misery. Within its unsanctified domain, youth withers; knowledge is extinguished; usefulness is entombed; and religion expires.”

Even in newspapers, such attitudes were reported as straightforward fact. “Convents,” The Harrisburg Herald reported in November 1854, “are the very hot-beds of lust and debauchery.”

Conspiracy theories always breed strange architectural imaginings. They start with something like the rumors of illicit sex between priests and nuns, and from there the allegations of unwanted pregnancies. But no children are around, so the infants must have been murdered. Where are the bodies buried? You start to envision deep catacombs, hidden structures, sub-basements and labyrinths. You must, because how otherwise to account for the lack of evidence? The idea of the subterranean, the house with secrets—all of this becomes an architectural necessity to explain where the dead are hidden.

These books were popular because they were both titillating and moralizing. They promised a world of illicit sex and fantasy while at the same time decrying such a world. For all their lurid detail, there was a heavy hand to the moral worldview here. Scipio de Ricci told his readers that the “sole object of all monastic institutions in America is merely to proselyte youth of the influential classes of society, and especially females; as the Roman priests are conscious that by this means they shall silently but effectually attain the control of public affairs.”

The convent was a space distinct from the home, and thus an affront to the role of the Protestant woman as a mother and wife. Women in the early days of the republic could not vote, and yet were envisioned as the keepers of democracy, because it was their job to raise sons and inject values into them. This is what the scholar Linda Kerber has called “Republican motherhood”: the complicated way in which women were held up as the vessels of American ideals even as they were denied access to political power. As such, men worried about secret subversion often fretted about the susceptibility of women to moral decay and degeneration, and assumed that foreign conspirators would target them as the key to bringing down America itself.

It was only a matter of time until these salacious rumors and simmering xenophobia burst forth into violence.

Boston’s Ursuline convent had opened in 1820, and quickly established itself as a leading school for the young women—both Catholic and Protestant—of the city’s elite. But it was far from the city center, looming up on Mount Benedict over its neighbors, mostly brickmakers and other working-class laborers. Relations between them and the nuns, particularly the mother superior, Sister Mary Edmond St. George, were tense. As one John Buzzell would later say of St. George, “She was the sauciest woman I ever heard talk.”

These local tensions were fueled by the rise of national anti-Catholic sentiment, and by the flood of lurid best sellers. So when, on the night of July 28, 1834, a young woman named Elizabeth Harrison fled the convent, the community was quick to see confirmation of their deepest suspicions. The woman, who had taught music there for 12 years, sought refuge with a local neighbor before being taken to her brother in Cambridge. There, distraught, she said that she didn’t want to return to Mount Benedict—for reasons that were never fully made clear. But within a few hours, the Bishop had arrived and was able to comfort the young woman, persuading her to return.

Years of anti-Catholic fearmongering now had a narrative to cling to. On August 8, a local newspaper ran an article headlined “MYSTERIOUS,” relating the story in brief and ending on a suspicious note: “After some time spent in the Nunnery, she became dissatisfied, and made her escape from the institution—but was afterward persuaded to return, being told that if she would continue but three weeks longer, she would be dismissed with honor. At the end of that time, a few days since, her friends called for her, she was not to be found, and much alarm is excited in consequence.”

That same weekend, Lyman Beecher (the father of Harriett Beecher Stowe and the abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher) delivered a series of anti-Catholic sermons in Boston, and though he would later claim that he had no influence on the events that followed, something was clearly in the air.

The decision to riot seems to have developed rather leisurely. Genuine concern about Harrison’s status was mingled with a long-simmering resentment toward these women who seemed to look down on their laboring neighbors. Local men began to talk openly of securing Harrison’s rescue and burning down the convent. Placards and posters appeared throughout the city that read: GO AHEAD. To Arms!! To Arms!! Ye brave and free the Avenging Sword unshield! Leave not one stone upon another of that cursed Nunnery that prostitutes female virtue and liberty under the garb of Holy Religion.

A week before the riot, a farmer named Alvah Kelley was holding court at a local bar, complaining about the Catholics; another patron asked if there was a plan to attack the convent, and “in a cool deliberate manner,” Kelley replied that if Harrison was not “liberated” within a few days, the nunnery would come down.

Early in the evening on August 11, St. George allowed a fact-finding mission: Prominent men toured the convent and found nothing amiss and Harrison apparently happy and fine. Satisfied, the group prepared a report to this effect to be published in the papers the following morning. But it was too late—by the time the report was published, the Ursuline convent was a smoking ruin.

By 11 p.m., a crowd had lit several barrels of tar on fire in a neighboring field to provide ready incendiaries and torches. St. George, sensing what was in the offing, threatened the rabble, telling them, according to one account, “The Bishop has 20,000 Irishmen at his command in Boston who will whip you all into the sea,” but this only infuriated them. Around midnight, men stormed the convent; after making sure that the nuns and their pupils had all been evacuated, they ransacked the place in search of the hidden crypts where the bodies of infants were buried, and in search of what they assumed would be Harrison’s corpse. They found nothing, but razed the building anyway.

Once it became clear that law enforcement would make no effort to put down the mob, the scene turned carnivalesque. John Buzzell broke into the bishop’s retreat inside the convent and draped himself with the bishop’s vestments. Rioters, disappointed in their search for dead babies, overturned coffins in the crypt and desecrated the remains. One of the students, Louisa Whitney, later described the mob’s cheery violence as the work of “amiable ruffians”; the Christian Examiner described the seen as “a sort of diabolical frolic, as if such an atrocity were no more than the kindling of a great bonfire.”

Having destroyed the nuns’ homes, the rioters seemed to think they had acted philanthropically. The morning after, some of the men told Whitney (according to her later court testimony), “We’ve spoiled your prison for you. You won’t never have to go back no more.” Whitney, who’d just seen her home burned to the ground, was incredulous: “The general sentiment of the mob seemed to be that they had done us a great favor in destroying the convent, for which we ought to be grateful to them.”

Following the riot, multiple men were arrested, but they would face no serious punishment. This marked the beginning of a major turn in America’s paranoid history. Anti-Catholicism became mainstream, a successful political posture. After 1854, newly elected lawmakers forced the Church to divest its real-estate holdings, transferring property to boards of trustees instead. “Nunnery committees” in Massachusetts and Maryland were founded to investigate convents over rumors of sexual abuse. (The Massachusetts committee ran into scandal, predictably, when the chairman himself was revealed to be engaging in sexual impropriety, using taxpayer money to pay for his mistress’s lodging.)

A book supposedly by an ex-nun, Maria Monk (but actually written by a group of Protestant preachers), Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal, yet another pornographic morality tale, appeared soon after and sold 300,000 copies, becoming one of the most popular books in antebellum America, second only to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In 1835, two more enormously successful books were published: A Plea for the West and Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States. Both warned that Protestant America was on the verge of being caught unawares by a new George III: the pope in Rome.

The panic abated only as concern began to shift away from the Vatican toward the more pressing crisis of slavery. In the South, those who enslaved others were riven with paranoia of uprisings and abolitionist saboteurs. In the North, fears focused instead on the slavocracy and its brutal political power. In 1854, the journalist Charles A. Dana wrote that “neither the Pope nor the foreigners ever can govern the country or endanger its liberties, but the slavebreeders and slavetraders do govern it, and threaten to put an end to all government but theirs.”

As for the convent itself, not much remains today, not even the hill on which it was built. The site where it once stood is now Broadway, a thoroughfare that runs through Somerville and connects Cambridge and Boston. A small public library sits there today, with only a small stone marker noting that the Ursuline convent “burned” in 1834. The hill itself, the text explains, was dug down in the late 19th century, which gave rise to the place’s current name: Ploughed Hill.

A hill that’s been ploughed, a name that testifies to its erasure. In a city known for meticulously preserving its history, it’s disorienting to see how little is said about what happened here.

Part of the reason these moral panics resurface so frequently is that they’re so easily forgotten. The same script gets recycled again and again, only to be memory-holed as soon as the fervor subsides. What happened in Boston in 1834 would resurface in 1920s, with the Ku Klux Klan’s willingness to use violence to defend against fictitious assaults on Protestant women’s “purity” by Catholics and Jews, and again in the ’80s during the Satanic panic, when children were coerced into accusing day-care employees and even their own parents of ritualistic abuse and murder. Contemporary conspiracy theories about Clinton’s murderous sex cabal may sound outlandish, but it’s only the latest page in a playbook that is more than 200 years old. If we remember this, perhaps we can rob the next panic of its heat and fury.

This essay is adapted from the author’s forthcoming book, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Atlantic can be found here.