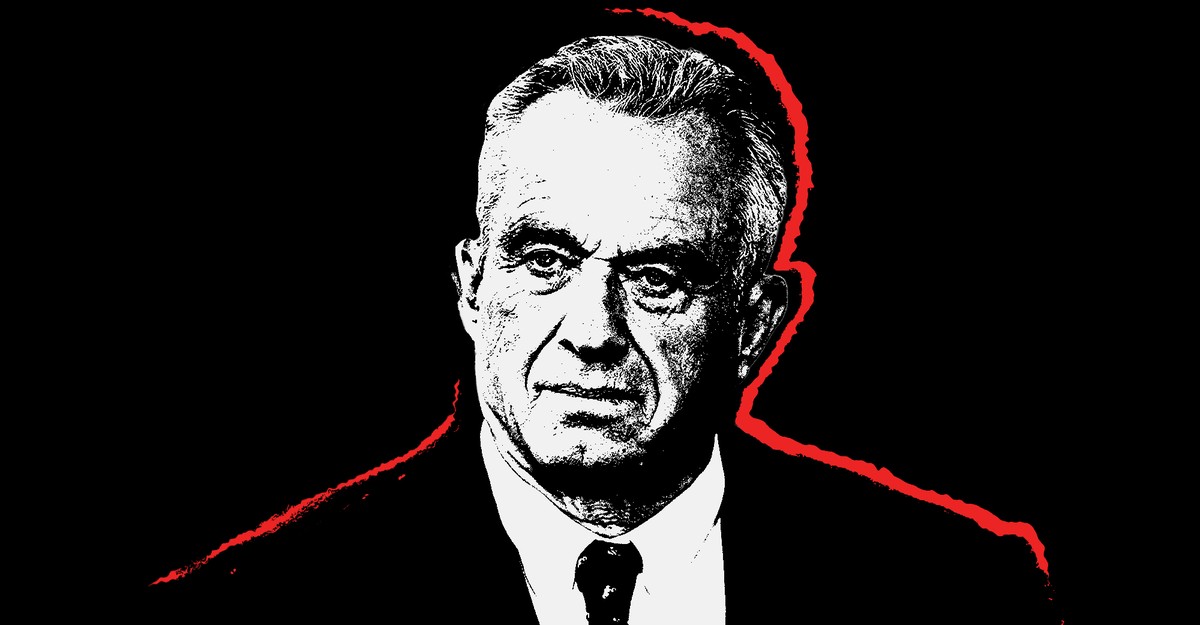

The Most Shocking Aspect of RFK Jr.’s Anti-Semitism

Last week, at a dinner event in Manhattan, the Democratic primary candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. shared his unvarnished thoughts about the nature of the coronavirus. “There’s an argument that it is ethnically targeted,” he explained, in remarks captured on video. “COVID-19 is targeted to attack Caucasians and Black people. The people who are most immune are Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.” To be sure, Kennedy added, “we don’t know whether it was deliberately targeted or not.” In other words, Kennedy apparently believes it is an open question whether the pandemic was engineered by a shadowy cabal to spare Chinese and Jewish people.

At least 1 million people in China have died from COVID-19; far from being immune to the virus, Jews in places like New York were often unfairly accused of spreading it. As a Jew who had his own bout with the coronavirus, Kennedy’s claims were news to me. But given the source, they also weren’t a surprise. That’s because Kennedy is a conspiracy theorist, and the arc of conspiracy is short and bends toward the Jews.

Here is just a small sampling of what Kennedy believes: that radiation from wireless internet causes cancer; that chemicals in the water supply are producing gender dysphoria; that the CIA killed both his father and his uncle, President John F. Kennedy; that antidepressants cause today’s mass shootings; that George W. Bush stole the 2004 presidential election; and that your phone’s 5G connection is part of a plot “to harvest our data and control our behavior.”

Seen in the context of Kennedy’s career, what’s surprising is not his foray into anti-Semitism but that it took him this long to arrive here. As I’ve written before:

Anti-Semitism is arguably the world’s oldest and most durable conspiracy theory. It presents Jews as the string-pulling puppet masters behind the world’s political, economic, and social problems. For those seeking simple solutions to life’s complexities, this outlook offers a ready-made explanation—and enemy. Anyone seeking a single source for society’s travails may start with run-of-the-mill conspiracy theories but will soon end up parroting anti-Jewish ideas.

Because anti-Semitism has produced centuries of material pinning humanity’s problems on its Jews, a person convinced that an invisible hand is conducting world affairs will eventually discover that it belongs to an invisible Jew.

For this reason, it is impossible to circulate on the conspiratorial fringe and not encounter anti-Semitism. This is why Kennedy has constantly found himself in the company of those who believe and express anti-Jewish ideas. Last week, he trumpeted his meeting with the rapper Ice Cube, a fellow conspiracy theorist who has a long history of bizarre anti-Semitic tweets and song lyrics. In the past, Kennedy has also made common cause with the hate preacher Louis Farrakhan, who regularly rails against alleged Jewish control of media and government.

That Kennedy would ultimately echo the anti-Semitic assumptions of his conspiratorial cohort was inevitable. Indeed, he is far from the first traveler on the well-trodden path from conspiracism to outright anti-Semitism. In recent years, individuals as diverse as Marjorie Taylor Greene, Kyrie Irving, and Elon Musk have graduated from garden-variety conspiracy theories to anti-Jewish arguments. Even the content of Kennedy’s COVID-19 conjecture isn’t original: Jews have been blamed for spreading plagues for centuries, most famously during Europe’s Black Death.

Over the weekend, Kennedy furiously tweeted denials and clarifications, insisting that he meant only that COVID served “as a kind of proof of concept for ethnically targeted bioweapons,” not that “the ethnic effect was deliberately engineered,” though he’d clearly raised that exact possibility in his original remarks.

Kennedy himself has no prior history of anti-Semitism, and has never evinced personal prejudice toward Jewish people. But his conspiratorial compass ensured that he would eventually arrive at this destination, because it points in only one direction.

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Atlantic can be found here.