He was there when JFK was shot, and he’s over the conspiracy theories

Those three shots — and the conspiracy theories that followed — have haunted him for decades.

Now 91, Joe Carter was on the press bus in the Dallas motorcade that day in 1963. He has struggled in the 60 years since, troubled by people whose wild ideas clashed with the dogged reporting he did in those early, raw moments after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“I didn’t know at that moment how deadly those shots were,” Carter said. And by deadly, he’s talking about more than the clanging violence, more than the blood and brain matter he saw on Jackie Kennedy’s clothes in the hospital, more than the nation’s massive spasm of grief at his death.

“To me, it unleashed an ugliness in the American people,” he said. For decades, he would not mention his role. “When I did, very often some nitwit would tell me what really happened. Shouting loudly. Not daring to call me a liar, but insinuating.”

The cancer has metastasized in recent years, fueled by the MAGA movement’s embrace of “alternative facts” and denial of election results. Amplified by keyboard warriors who’ve never heard fatal gunshots or knocked on a door to ask questions, the lies rage on — resulting in a different type of harm. And now the flash of conspiracy theories is being reignited by Kennedy’s own nephew, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is challenging President Biden to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee in 2024.

A vocal anti-vaxxer who suggested the coronavirus was engineered to spare Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese people, equated mask mandates with the Holocaust, and said chemicals in the nation’s water supply are turning people transgender, Kennedy is also reviving the theory that the CIA had something to do with his uncle’s assassination, that Lee Harvey Oswald was working for them.

Beloved in his luxe circle of conspiracy-theory-embracing friends in Malibu and Napa Valley, Calif., Kennedy also doubts that Sirhan B. Sirhan acted alone in the assassination of his father, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, in 1968. He even told The Washington Post’s Tom Jackman about his prison visit with Sirhan.

Kennedy family members were denouncing his claims all week.

Jack Schlossberg, John F. Kennedy’s grandson, called his cousin’s campaign an “embarrassment” and a “vanity project” in an Instagram post. “I’ve listened to him. I know him. I have no idea why anyone thinks he should be president,” he said.

Schlossberg accused him of “trading in on Camelot, celebrity, conspiracy theories, and conflict for personal gain and fame.”

Carter said he places him in the “nitwit class,” but said his name gives his lies a larger platform and a “funky credibility.”

“He undermines much more in America’s democratic system, in my view,” Carter said. “This part I take personally.”

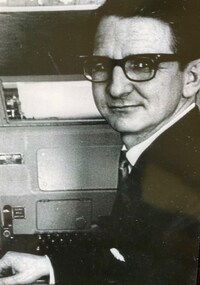

Carter was an Army veteran and 31 years old working as a police reporter in the United Press International’s Dallas bureau when his editors asked him to join the presidential team covering Kennedy’s visit on Nov. 22, 1963.

He remembers the tension among the press corps that day.

Texans weren’t supposed to have high regard for the Kennedys and their Camelot. During the campaign in 1960, a hostile, conservative crowd swarmed and harassed then-Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson and even grabbed Lady Bird’s gloves and threw them in the gutter. Two years before he was assassinated, Kennedy was rebuked by Ted Dealey, then the publisher of the Dallas Morning News, who said at a White House luncheon “that the country needs a man on horseback, and Kennedy is riding around on Caroline’s tricycle,” Stephen Fagin, curator of the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, told The Post.

“Now I was being a very cautious reporter,” Carter said, remembering the people gathered along a barricade to greet the Kennedys as they arrived at Love Field. “I was waiting for someone to do something nasty along that fence. Nothing happened. They were great.”

He boarded the press bus and sensed the relief of the White House press corps. “There were no nasty signs as we drove toward downtown,” he said.

Then suddenly, the caravan stopped. “We all leaped to our feet,” he said. They anticipated a conflict.

“But Kennedy stopped to talk and to, you know, shake hands with some school kids,” he said. Again, they exhaled.

Then, those three shots.

Carter had recently left the Army, where he was trained to the same level of marksmanship that Oswald, the shooter, had reached in the Marine Corps.

He ran toward the front of the bus, toward the gunshots. The other reporters, used to covering policy and politics, looked at him in horror and awe as he tried to stop the bus and get off.

Instead, the bus sped on and Carter followed the story, winding up in the hospital, where he watched a bronze casket wheeled out and a stoic, blood-spattered first lady follow it. He used his last dime to phone that scene in.

In the days that followed, Carter and an entire nation of journalists followed tips and leads after Oswald was arrested. The work in those days — knowing how hard everyone ran down every possibility, triple-checked every fact — and the exhaustive investigation by the Warren Commission convinced Carter that Oswald acted alone.

Carter had a long career in Washington after that tumultuous year. He eventually retired in his native Oklahoma, back where he was born during the dust bowl, where his dad was a cowboy trying to feed eight kids during the Great Depression.

But those three shots — and the idea that popular culture’s obsession with conspiracy theories began with a nation questioning their origin — keep Carter from exhaling.

“Let me say, there are not alternative facts. What happened, happened,” he said. “But you know, with Bobby Kennedy Jr. … I know the pangs of losing your father and he lost his father and that’s so sad. But that doesn’t mean he gets to twist history.”

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Washington Post can be found here.