The contrails conspiracy is not only garbage, it’s letting aviation off the hook too | George Monbiot

You spend years trying to get people to take an interest in aircraft emissions. Then at last the issue gets picked up – but in the most perverse way possible.

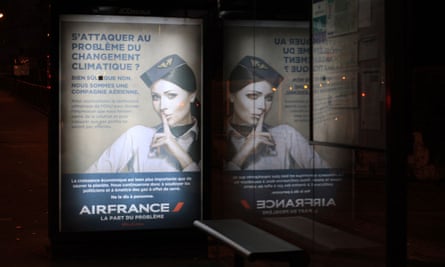

The pollutants spread by planes are a major issue. They make a significant contribution to global warming, yet they are excluded from international negotiations, such as the conference taking place in Paris. As a result, aviation’s expansion is unchecked by concerns about climate change.

This exclusion is ridiculous, not least because aircraft emissions have a particular role in heating the planet, due to the height at which they are released, and the multiplying impacts of the water vapour and other gases the planes produce. Gases that sometimes form contrails in the sky.

You might expect me to be delighted by the fact that thousands of people are taking an interest in contrails and their effects, and campaigning against the airlines producing them. Far from it.

The most vocal people protesting against aviation emissions have no interest in their contribution to global warming. Quite the opposite. Many of those now denouncing the pollution of the skies see climate science as part of the problem: a conspiracy by corporations, military planners and other nefarious interests to control the skies.

Until recently, I ignored this movement, even as it spread among people I knew. So pervasive have the rumours become that the government, which seldom responds to conspiracy theories, felt obliged this summer to produce a factsheet debunking the principal claims.

But it was only when the editor of a major environmental magazine sent me what he called “a remarkable essay” in the hope of persuading me to take up the cause that I decided I could ignore it no longer. The “remarkable essay” was garbage: a long series of disconnected facts tacked together to create what appears to be a coherent narrative, but that bears as much relationship to reality as a speech by Donald Trump. On a bad day.

In my home town, the streets are now littered with graffiti advertising the website www.look-up.org.uk. So I looked it up. You might imagine, in reading what follows, that I’m picking an extreme example, but I’m sorry to say this is typical of the hundreds of sites promoting this nonsense. I keep meeting otherwise-intelligent people who seem prepared to believe it.

Here are its main contentions:

- “Planes are not supposed to make clouds and yet we see them doing so in our skies every day.”

- “Three huge global corporations now own almost all of the world’s airlines. They have modified their aircraft to spray chemicals unknown into our skies during flight.”

- “Large private, corporate organisations [are] … modifying our atmosphere without the knowledge and consent of society.”

- “We think their insane plan to block our sunshine is unnecessary, dangerous and nothing to do with science or protecting us, but more to do with financially motivated weather control.”

You can see the impacts everywhere. The authors of the website note that “virtually the entire month of November has been a ‘white out’… unbroken cloud characterised by a thin, translucent, white blanket of chemicals sprayed from aircraft.”

Cloudy skies in November – hmmm, fishy to say the least.

So why are “they” doing it? Well, it depends which part of this website you read. On some pages it claims that the contrails (or “chemtrails”) are being used to “manipulate the CO2 figures”. This will then justify the mass re-engineering of the atmosphere. On other pages, the contrails themselves are being used to re-engineer the atmosphere, using unspecified chemicals to change the weather.

Who profits from this “financially motivated weather control” and how is left strangely vague, though of course the beneficiaries include “very well paid scientists”. Don’t they always? As everyone knows, scientists are rolling in money, which is why so many oil company executives leave to take up more lucrative careers as university lecturers.

The scientists’ mysterious benefactors must be extremely powerful, however, as they engineered the Paris attacks (“another false flag event”), in order to leave nothing to chance during the climate talks.

Everything confirms the thesis, even the dismal number of followers the site has managed to attract. That’s down to the role of Facebook – or Fakebook as they prefer to call it – in the conspiracy:

“We hired some clever people to analyse the behaviour and reach of our posts and they concluded that algorithmic restriction had been put in place to restrict the reach of our posts to just a few people, a small group of subscribers, and it was normally the same people every time.”

What other explanation could there be? And wait – it turns out that even the subscribers are in on it:

“We also suspect some, if not all of those people are operatives who regularly like our material to ensure we think we were getting an audience, whereas almost nobody was seeing the material at all.”

So on one hand we have a real threat, measurable and attestable, that is caused by an identifiable industry and persists as a result of the indifference and short-termism of the world’s governments. On the other, we have a conspiracy, attributed to forces unknown and interests unspecified, so powerful and pervasive that it extends from Mark Zuckerberg to the Paris terrorists. Why does it seem to be harder to generate interest in the real issue than the improbable one?

The real issue – global warming caused by aircraft emissions – calls on us to act. Reducing our impacts means flying less; something that few people are prepared to do. It involves an exhausting battle against a powerful industry and unresponsive governments. It means reading boring papers, attending boring meetings and engaging with a level of political and technical complexity that many people find repulsive. There’s plenty of grind and precious little glory.

But there’s nothing boring about conspiracy theories. They make sense of what can sometimes feel like a senseless world. They tell you that you are among the elect: aware of a grand scheme that other people (or sheeple or sleeple as the conspiracy sites often like to call them) are unable or unwilling to see. It tells you that you are a lonely crusader fighting evil of the kind that’s otherwise encountered only in films about superheroes.

And if hardly anyone reads your website, it only goes to prove how important you are: why else would the authorities go to such lengths to limit your followers?

It also absolves you of the responsibility to act. Sure, you might feel moved to create a website, take some photos, perhaps sign the odd petition or even attend one or two noisy demonstrations. But you don’t have to change anything, because somewhere, buried deep in the forebrain, is the knowledge that there’s not really anything to change. You get the glory without the grind.

Perhaps such movements are also a response to a sense of helplessness. In a world so complex, chaotic and badly governed that its most dangerous predicaments often seem intractable, it is paradoxically comforting to believe that godlike powers are in control, even if those powers are malign.

We distance ourselves from uncomfortable realities by creating comfortable unrealities. And it doesn’t seem to matter how unreal they may become.