Russell Brand: How the comedian built his YouTube audience on half-truths

PA Media

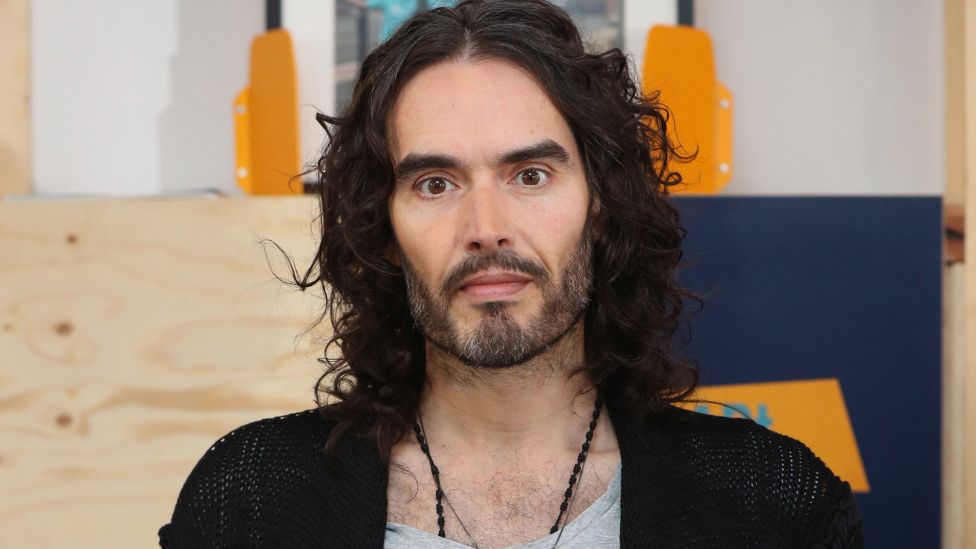

PA MediaThe first time Russell Brand really dipped his toe into the water of conspiracy theories, in early 2021, the effect was swift – a YouTube channel whose videos normally received about 100,000 views was suddenly visited by more than a million people. It won him a new income stream and a fresh army of fans.

It is also where, on 15 September, he posted a video denying accusations of rape, sexual assaults and emotional abuse between 2006 and 2013.

So how did Brand get so big on YouTube?

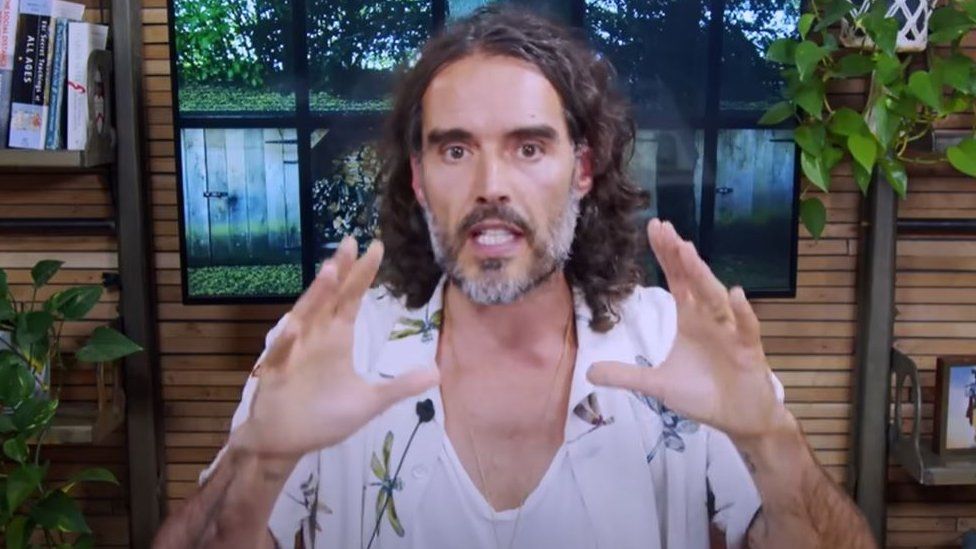

“BOMBSHELL lab leak report,” his YouTube grid now screams. “You’ve Been LIED To About Why Ukraine War Began”. Scroll a little and, “Bill Gates Has Been HIDING This And It’s ALL About To Come Out”. The channel serves as a time capsule of Brand’s latest persona, honed since the Covid pandemic.

A veteran of the streaming platform, for roughly a decade he has posted on a broad range of topics, from politics to celebrity. In lockdown, he posted a video of him making soap with his wife.

But it was not until early 2021, when the tone of his videos shifted, that his audience started rising more sharply – almost doubling to nearly five million by the end of that year.

His following on YouTube now stands at 6.6 million, alongside multimillion-strong followings on X, formerly known as Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

The door to this new fan base might have creaked open when Brand first discussed “the Great Reset” – a vague set of proposals from an influential think tank to rebuild the global economy after Covid. Parallel to this real report, a hazy theory that this represented proof of a plot to control the world’s population and strip people of their freedoms, emerged.

At the time, Brand did not seem to be promoting that view.

“There are some people out there that believe in shady global cabals running things from behind the scenes. Now I don’t believe that – I believe that there are plain visible economic interests that dominate the direction of international policy,” he said.

Nevertheless, the very mention earned his video more than a million views, compared with the average 100,000 to 200,000 his videos were getting at that time. His next video on the Great Reset was watched almost three million times.

Subsequent video titles shouted: “The Great Reset is HAPPENING” and is “NOT a conspiracy!”, each again racking up between one and three million views.

Words like “lie”, “hid” and “exposed” began to appear more often in headlines.

Brand’s coverage of wider politics, celebrity and relationships started to take a back seat.

Covid and vaccines, the idea that institutions are lying to you, and later the Ukraine war came to the fore.

His channel’s transformation was complete. And it worked for Brand – his following grew much more rapidly than before.

“Leaders tend to be created by followers rather than the other way round,” says Dr Carol Jasper, a social psychologist at the University of Stirling.

“I suspect Brand has been emboldened by his following, encouraged by the popularity and motivated to continue,” she says, adding that making money could have been another incentive.

Social media analytics company Social Blade estimated Brand could be making up to £4,000 per video.

YouTube announced on Tuesday it had stopped Brand earning money from his videos.

Russell Brand allegations

A cursory glance at Brand’s YouTube channel could suggest someone with a deep belief in conspiracy theories.

But Dr Jasper thinks the reality is more nuanced.

“He stopped short of actively endorsing conspiracy theories on a number of occasions,” she says.

He also mixes in “healthy scepticism” with arguments that are “largely fact-free”, Dr Jasper says.

“Stopping short of having lots of specifics in a message can actually be quite useful, because the reader or the listener then sort of fills in the blanks,” she says.

This would allow content to be accessible to a wider audience.

On Covid, for example, Brand raised concerns that vaccine passports could be discriminatory and that the vaccines themselves were not being shared fairly around the world. These are concerns shared by the UK equality watchdog and the UN.

But he also regularly, baselessly, suggested the only reason vaccines were being recommended was because money was changing hands – excluding the fact they had dramatically reduced the number of people dying.

He will present “nuggets of truth” but frame them as being explained by, “global, controlling, usually nefarious cabals who are intent on harm”, in ways that are not verifiable, Dr Jasper explains.

On the Ukraine war, Brand discusses the complexity of the country’s political situation.

But at the same time, he speaks of a claim believed to have been sown by the Kremlin, that the war had something to do with the existence of US-funded “biolabs” in Ukraine.

“There are no biolabs in Ukraine – that’s a conspiracy theory,” Brand says. “There’s biological research facilities… but that’s completely different.”

Disinformation-tracking company Logically has explained that: “In the context of Russia’s claims, [a biolab] is supposed to mean a place in which biological weapons are engineered,” whereas what Ukraine has are biological research facilities which are “working to counter potential diseases and outbreaks”.

Its head of investigations, Joe Ondrak, suggests Brand stops short of delivering a conspiracy theory himself, but gives audiences “the ingredients to make the disinformation themselves”.

He says that people using this kind of tactic say: “I’m not saying this. But look at these dots. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if you brought some red string along [to connect them]?”

And rather than committing to a specific viewpoint, Brand, “flits around between different narratives”, Mr Ondrak says, “circling around saying that bit in the middle that would get him in trouble.”

He explains how engaging with stories like Ukraine biolabs, that were already going viral, also helped Brand gain popularity.

“He’s a fixture, but he’s never the one to really push forward a story,” Mr Ondrak says.

By joining conversations that are already happening – for example on hot-button topics like ivermectin, vaccine passports and elements of US politics, including Donald Trump – big spikes in viewership have followed.

Where he was previously racking up about 100,000 to 300,000 views per video, posts on these topics gained him figures in the millions.

Now, videos featuring figures associated with the “alt-right” in the US, like Tucker Carlson, outperform earlier interviews with celebrities including actor Emma Watson and presenter Jameela Jamil.

A recent interview with Bear Grylls about surviving in the wild, more similar to Brand’s old style, saw his viewing figures back down to 167,000 views.

All this means, by the time the allegations were made, Brand’s subscribers included many who were mistrustful of the mainstream media and were happy to come to his defence.

It was a ready-made following, Dr Jasper suggests, primed to say that he was being targeted for “telling the truth”.