How misinformation endangers us

technology

In association with

Six months after New Zealand first went into lockdown and a spate of arson attacks on cell towers began, we now have a better idea than ever before of how misinformation works and how it threatens us, Marc Daalder reports

The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked widespread concern around the spread of misinformation – particularly of a medical or scientific nature – online.

While research from Te Pūnaha Matatini shows conspiracy theories around the virus have not become more prevalent since the start of the pandemic, it also shows the tenor of those theories has quickly evolved towards an aggressive and anti-establishment ideological position.

The greater focus on misinformation in light of the pandemic has also highlighted the way false information affects our society and economy. The string of arson attacks against cellphone towers over lockdown has meant 5G has been a particular area of focus for researchers, journalists and conspiracy theorists alike.

Although there are many other topics that are the target of misinformation, 5G can serve as a useful lens for understanding how misinformation spreads and how it affects us – and perhaps even what we can do about it.

Pre-bunking

To start with, experts advise against directly addressing or attempting to debunk conspiracy theories.

Jess-Berentson Shaw, a co-director of The Workshop and an expert on the science of communication, including misinformation, has repeatedly raised concerns about the drive to debunk when it is so ineffective. In February, she told Newsroom the Ministry of Health should adopt alternate techniques.

“I think their natural inclination would be to debunk,” she said at the time, “and I think they need to avoid doing that actually. Generally as an overall strategy, they need to get really clear on what the story that they want to tell about coronavirus is.”

Instead, we should seek to preempt misinformation by spreading true information – while warning that people may at a later date see false information on this topic. This is what Berentson-Shaw calls inoculation or pre-bunking.

“Pre-bunking is where, before people are exposed to bad information, you can get in there first and let them know that they might hear this information and it will be false,” Berentson-Shaw told Newsroom in November. “That really relies on the ability to get in there first.”

It’s also a strategy that has proved effective at countering the spread of extremist ideologies.

Caleb Cain, a former alt-right true believer who now works on deradicalisation projects at American University, told Newsroom the far-right use pre-bunking to great effect.

“”Take Stefan Molyneux for example,” Cain told Newsroom in March.

“He’ll be like, ‘When you go to college, they’re going to force you to take gender studies classes and in those classes you’re going to learn about intersectional feminism. They’re going to tell you it’s about equalising power and helping minorities and raising people up. Really all it is, it’s about cutting you down, so they control you, so they can control all of us. It’s all just a form of manipulation and it’s a lie.’

“Then they’ll prime you against words like problematic. They prime you against the language. They prime you against the buzzwords like intersectional feminism. By the time you hear that stuff, you have an aversion to it – like you have a physical disgust, aversion. If I was having a conversation with you back then and you said ‘problematic’, everything else you said after that would have been static.”

Cain wants to use the same strategies to inoculate vulnerable people against radicalisation by white supremacists and Berentson-Shaw says studies overseas have shown that warning young people about the likelihood or possibility of medical misinformation makes them less susceptible to it.

What is 5G?

So, given this article will discuss 5G and misinformation, let’s begin with some pre-bunking of our own: What is 5G and how does it work?

According to a fact sheet created last year by Juliet Gerrard, the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor, 5G is the fifth generation mobile network and, like its predecessors and AM and FM radio, it works through radio waves.

Radio waves can vary in intensity (their size) and frequency (how often they arrive). In the early stages of New Zealand’s 5G rollout, where we are now, the frequency is in the same range as 4G waves. As the rollout continues, some of the network will begin to use millimetre waves, which have a higher frequency. This allows 5G to send data much more quickly than 4G.

Because the wavelength of these waves will be smaller (wavelength and frequency have an inverse relationship), they’ll have a harder time travelling distances and piercing through obstacles. That means a millimetre wave 5G network requires more towers than 4G to ensure the same amount of coverage.

“The currently available scientific evidence makes it extremely unlikely that there will be any adverse effects on human or environmental health,” the website states.

Frequency wouldn’t be the concern for health effects – intensity would.

While the radio waves used in 5G (and 4G and 3G and 2G and regular old radio) are technically a form of radiation, the standards set in place ensure the intensity remains well below anything that could be threatening to human health. Radiation sounds like a scary word, Gerrard says, but light itself is a form of radiation.

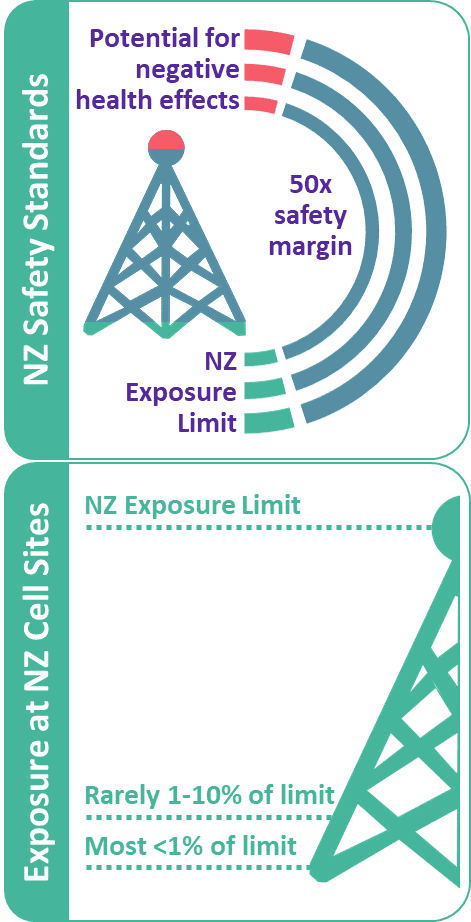

For radio waves, the legal exposure limit for intensity is set 50 times below the point at which they could endanger human health. Even more reassuring, Gerrard notes, tests at cell sites show the actual exposure level is generally below 1 percent of that legal limit and very occasionally between 1 and 10 percent.

(This chart from the Chief Science Advisor shows radio waves in New Zealand occur at levels well below the point where they might endanger human health.)

“It would take you a very long time to fry an egg with a 5G beam,” Gerrard jokes.

“People don’t think of it like that. They hear the wavelength and the frequency and they extrapolate from there rather than thinking about the intensity. It’s like waves on a beach. Lots of little waves aren’t going to hurt you, but one big one could knock you over. It’s the intensity of the radiation that is the thing that people are missing.”

Why the distrust?

That seems straightforward, but why then do people not trust it – and how widespread is that distrust?

A recent survey by the Telecommunications Forum (TCF), an industry body representing the country’s telcos, shows most New Zealanders appreciate the potential benefits of 5G.

Some 85 percent “think it will be important for New Zealanders to have access to even better, faster mobile data networks in the next few years, and a similar percentage (86%) think it’s important for them personally to have fast, reliable access via their smartphone”. Seven in ten New Zealanders even say 5G is the way to achieve that.

But when asked what they know about the technology, the numbers were a bit less reassuring. Less than a quarter were “confident” in their knowledge of 5G four in 10 said they knew “a little bit” about it and 36 percent said they knew nothing. At the same time, six in 10 correctly said 5G was about as safe as preexisting mobile technology, 13 percent said it is safer and 15 percent said it was less safe.

When asked whether they agreed with the statement that 5G is safe “as it is simply a more advanced use of radio technology”, 53 percent said yes. Another 36 percent said they didn’t know and 12 percent disagreed with the statement.

While that range (12 to 15 percent) of people who think 5G is unsafe might seem sizeable, there are likely to be a couple of different groups of people within it.

Some of them might be people who doubt the safety of the technology but are more on the fence, as opposed to the smaller core of die-hard anti-5G activists. Knowing who you’re dealing with can help you determine how – or whether – to address peoples’ concerns.

“There’s always going to be those people that you can’t convince. And what you want to make sure is that they don’t get traction or pull into the mainstream. So you need that alternative narrative there,” Gerrard said.

Nicky Preston, a senior communications lead at Vodafone NZ, agreed.

“The reality is, there’s always going to be that 2 to 3 percent of people, or 5 percent of people, who are sceptical and we’re never going to change their minds. We have to be a bit realistic in that we’re much better to focus on the 80 to 90 percent of people who don’t know all the facts, and want to understand what 5G is and why it benefits communities and why it helps New Zealand businesses stay competitive,” she said.

Different communities might also have different reasons for not trusting the official message on 5G. Karaitiana Taiuru, a longtime tech industry expert and the author of the world’s first set of indigenous guidelines on AI, algorithms, data and the Internet of Things, has previously noted the variety of reasons why Māori could doubt the prevailing narrative on 5G.

“Historically there has been widespread intergenerational mistrust by Māori with the New Zealand government dating back to early settlers with broken contracts, theft and various other crimes against Māori,” he said after a spate of arson attacks against cell towers in Māori and Pasifika communities in May.

“Based on recent research and Waitangi Tribunal applications and hearings, government departments and entities, such as Courts, social services, Police and the education system, have proven to still have inherited biases and stereotypes against Māori. One impact of these biases in the education system is that Māori are underrepresented in sciences, engineering and other technologies, creating a wide knowledge gap on topics such as 5G.”

Preston told Newsroom, anecdotally, that the Covid-19 pandemic seems to have altered the magnitude and tenor of the opposition to 5G.

“All countries seem to be dealing with this in slightly different ways. In terms of the arson attacks – the actual, physical attacks on cell sites – New Zealand’s actually seen more attacks than many other countries in the Vodafone network,” she said.

“Despite causing massive disruptions, in some ways the far-out Covid-19 conspiracies helped to reassure most New Zealanders, because I think people go, ‘Surely Covid-19 is not caused by mobile radio waves or by Bill Gates’. Once most people think that through, they take Covid-19 a little more seriously and dismiss misinformation around 5G a little more easily”, she believes.

Gerrard also saw some upsides in the Covid-19-related misinformation surge.

“I’m an optimist, so I think in some ways it’s been helpful in that it surfaced a lot of that anti-science belief and you can see it for what it is,” she said.

The impact of misinformation

Misinformation does more than just mislead people – it can have knock-on impacts on our society and economy.

The false information around 5G is likely responsible for the spate of arson attacks on cell towers this year – although Preston is quick to caution that, with only one alleged perpetrator caught, no one can say for sure what motivated all of the attacks. Video footage of at least one of them, however, shows the person discussing 5G in negative terms.

“It costs a lot of money to build a cell site and maintain connectivity that serves communities. On one hand, we’ve got communities asking us for more cell sites – they want better mobile coverage or they’re experiencing buffering or lag because there’s not enough capacity in a certain area – and then on the other side you’ve got a small minority burning down cell towers,” she said.

“For us, it’s a cost. It’s really a significant amount of money to upgrade or replace this community infrastructure. And it’s also a safety issue. Thankfully the attacks that we’ve had have damaged cell sites but haven’t completely taken them out.”

There’s also redundancy built into the system in the event of power failures or adverse weather events. But if the right conditions are struck, entire regions could lose coverage, she warns.

“If it’s a remote cell site, it could really cause issues in that, if no one can connect to the cell site, they can’t make phone calls. They might not be able to call 111. There could be real negative outcomes for the community, not able to reach police or emergency services.”

Misinformation also has an impact on Vodafone’s operations and its staff, she says. The arson attacks and the spread of misinformation has led even some Vodafone staff to raise concerns.

“The impact on us is time, cost and effort. We could spend a lot more time actually promoting benefits of technology or helping New Zealand businesses innovate as opposed to having to correct the misinformation out there,” she said.

It also threatens New Zealand’s ability to roll out a world-leading digital economy.

“We really want to contribute to a safer Aotearoa and create a better New Zealand for everyone – by providing better access to technology. By launching 5G, New Zealand became the 22nd country in the world to have access to the next generation mobile network,” Preston said.

“Technology is an enabler and it could be the biggest export opportunity for New Zealand. We’re a small country with finite resources, however the scale that technology offers is massive. Xero is a great example of that.”

And Taiuru says Māori risk getting left behind.

“If you have Māori communities saying, you know, 5G is bad, then you’re going to have whole communities who won’t want to get on the bandwagon and take advantage of the technology. It’s a unique opportunity for Māori to actually be leaders in this new technology,” he said.

“We have an allocation of [5G] spectrum and I don’t know what the group’s doing with that, but to me, we could set up training schools, wānanga, work with Māori education providers and train up anyone to use these technologies. If we look at the 3G model, arguably, you could say that didn’t really benefit Māori in a longer-term sense. That was more about selling the spectrum to another telco provider.

“I would suggest that we should look at using a different model. Not selling the spectrum, just using it for ourselves. Create products, create our own research. That’s the way that we’ll get the technical skills that will certainly help Māori out of all the negative demographics.”

But that won’t happen if Māori communities reject 5G, he says.

Other forms of misinformation can also have adverse impacts. Overseas, the University of Oxford has found that belief in coronavirus conspiracy theories reduces compliance with public health measures, including social distancing, staying home, not visiting friends and family during lockdown, willingness to be tested for Covid-19 and wearing a face mask.

“Conspiracy beliefs are likely to be both indexes and drivers of societal corrosion. They matter in this context because they may well have reduced compliance with government social distancing guidelines, thereby contributing to the spread of the disease. One consequence of this national crisis may be to reveal fully the harmful effects of mistrust and misinformation,” the study found.

“Higher levels of coronavirus conspiracy thinking were associated with less adherence to all government guidelines and less willingness to take diagnostic or antibody tests or to be vaccinated. Such ideas were also associated with paranoia, general vaccination conspiracy beliefs, climate change conspiracy belief, a conspiracy mentality, and distrust in institutions and professions.”

Tackling misinformation

What can we do about this? To some degree, this is a systemic issue, rooted in centuries of colonialism, the architecture of social media and the rising distrust in previously-authoritative sources like the media or academia.

That means it needs a system-wide solution, from the community level to central government and everyone in between.

On the lower tiers, Vodafone has sought to engage with communities that have been most affected by the arson attacks in recent months.

“We need to introduce 5G for the development of our network and New Zealand needs it for the ongoing development of our country,” Preston said.

“What we’re doing is trying to address community concerns and share information from reputable government sources. We’ve done community workshops to understand people’s thoughts about 5G – understanding their concerns, and opportunities that they think it will come with. If we can start combatting some of this misinformation with real information, or using humour to beat the rumours, then maybe it might help to convince some of the people who still aren’t sure that it’s okay.”

“Listening is a technology that we don’t employ enough,” Berentson-Shaw said. “I think if you’re going to engage in a listening exercise, it’s much more effective than a communication, mythbusting exercise.”

Preston said many of the people who attended the early engagement meetings weren’t there to discuss misinformation, but simply wanted to learn how the advent of 5G would affect them. A major topic was the way it would improve video calling.

“One impact of the pandemic is that people really understand the importance of online [connection] more than ever before.”

Taiuru said there was a role for community leaders to play in touting the benefits of the new technology as well.

“If government and telecommunication providers actually engaged with Māori leaders, that would definitely go some way to solving some of the issues. But I saw recently Hone Harawira speaking out about the conspiracy theorists and also Matthew Tukaki has been speaking out about the theories as well, but they’re only two prominent Māori leaders speaking out,” he said.

“I don’t see any reason why we can’t have more engagement, more leaders speaking out. We have Māori economic advisory groups, the Iwi Leaders Forum, we have a lot of corporate iwi. I don’t see why they can’t be engaged or why they don’t take the lead in this area.”

But Preston says social media companies also bear some responsibility for these issues, given the way their platforms amplify misinformation and shroud users in anonymity.

“The other part to it is the social media platforms, and how they can play a bigger role in helping combat the misinformation on their platforms,” she said.

“Quite frankly, social media platforms have a moral responsibility. But also from an operational perspective and the amount of money they make from advertising revenue. This includes the functionality their platforms have introduced, providing a forum for conspiracies to flourish. Surely they can invest a little bit more in combatting some of the misinformation that’s now swirling on their platforms, because really it’s creating a health issue.”

Berentson-Shaw says there’s still room for more research about social media’s part in the spread of false information.

“I would like to see more of a structural and systems analysis on where that false information spreads in social media. Again, there’s been just so much research on the role of false information, how social media specifically works to spread false information. What are the role of social media companies in this? What’s the New Zealand government’s role to encourage or incentivise social media companies in this space?”

Then there’s a role for central government as well in working with communities, engaging with (or regulating) social media companies and building plans to preempt misinformation into its crisis response plans.

“Partly it’s government providing factual information, reassuring citizens about the science. And they have been really good at doing that,” Preston said.

She also said that Jacinda Ardern’s rebuke of 5G conspiracy theories during lockdown – prompted by a question from a reporter about the prevalence of such theories – was immensely helpful.

“The fact that the question was asked and that it was negated in such a way was super helpful for us. People go, ‘aw, if someone like Jacinda Ardern who most people trust, if she can assert this is false, then I should trust her’.”

Berentson-Shaw believes that responding to misinformation needs to be outlined in every future pandemic plan – and that we’re already missing an opportunity to preempt anti-vaccine sentiment ahead of the eventual rollout of a Covid-19 vaccine.

“I think that the implications of people believing false information about Covid are serious. Getting in front of it has to be part of the pandemic plan. That has to be part of any general approach to what I would call public health. Our communications environments and our information environment is now one of those key environments that determines our health,” she said.

Preston also believes misinformation is a health risk.

“Misinformation is a health issue. It’s a silent pandemic that is creating a new health crisis,” she said.

“We’ve obviously got a real global health crisis with Covid-19, but we’ve also got this information health crisis with people concerned about negative health impacts and conspiracy theories, where they really just shouldn’t be.”

Vodafone is a foundation partner of Newsroom