What happens when you turn a psychopath into a therapist?

I. The Oak Ridge experiment

The male patients sent to St. Thomas were all considered “graduates” of a treatment program at the Oak Ridge Psychiatric Unit in Penetanguishene, for years Ontario’s only forensic hospital for those who were found criminally insane.

The hospital housed some of the country’s most notorious offenders, men like Peter Woodcock, who had been convicted of murdering three children in Toronto in the late 1950s, and David Lariviere, a reputed mafia hitman who’d also killed a woman with a wine bottle as she lay sleeping beside him.

For more than 15 years, patient-inmates at Oak Ridge were subjected to experimental treatments that included sensory deprivation, hallucinogenic drugs and physical punishment.

The program has since been called “flagrant and outrageous” by an Ontario Superior Court judge. But 50 years ago, it was considered avant garde by many in the psychiatric community.

The unorthodox program was the brainchild of Dr. Elliott T. Barker, who in the mid-1960s was a newly minted psychiatrist fresh out of the University of Toronto.

He’d been inspired by the work of British psychiatrist Dr. Maxwell Jones, who’d developed the concept of a “therapeutic community” for the treatment of the mentally ill. A fundamental component of a “therapeutic community” was that patients would take an active role in their own treatment and serve as role models to each other.

The year after graduation, Barker and his wife travelled the world, visiting a Chinese prison camp in Maoist China to observe behaviour control techniques, to a kibbutz in Israel to meet with philosopher Martin Buber and to therapeutic communities in Britain and Denmark.

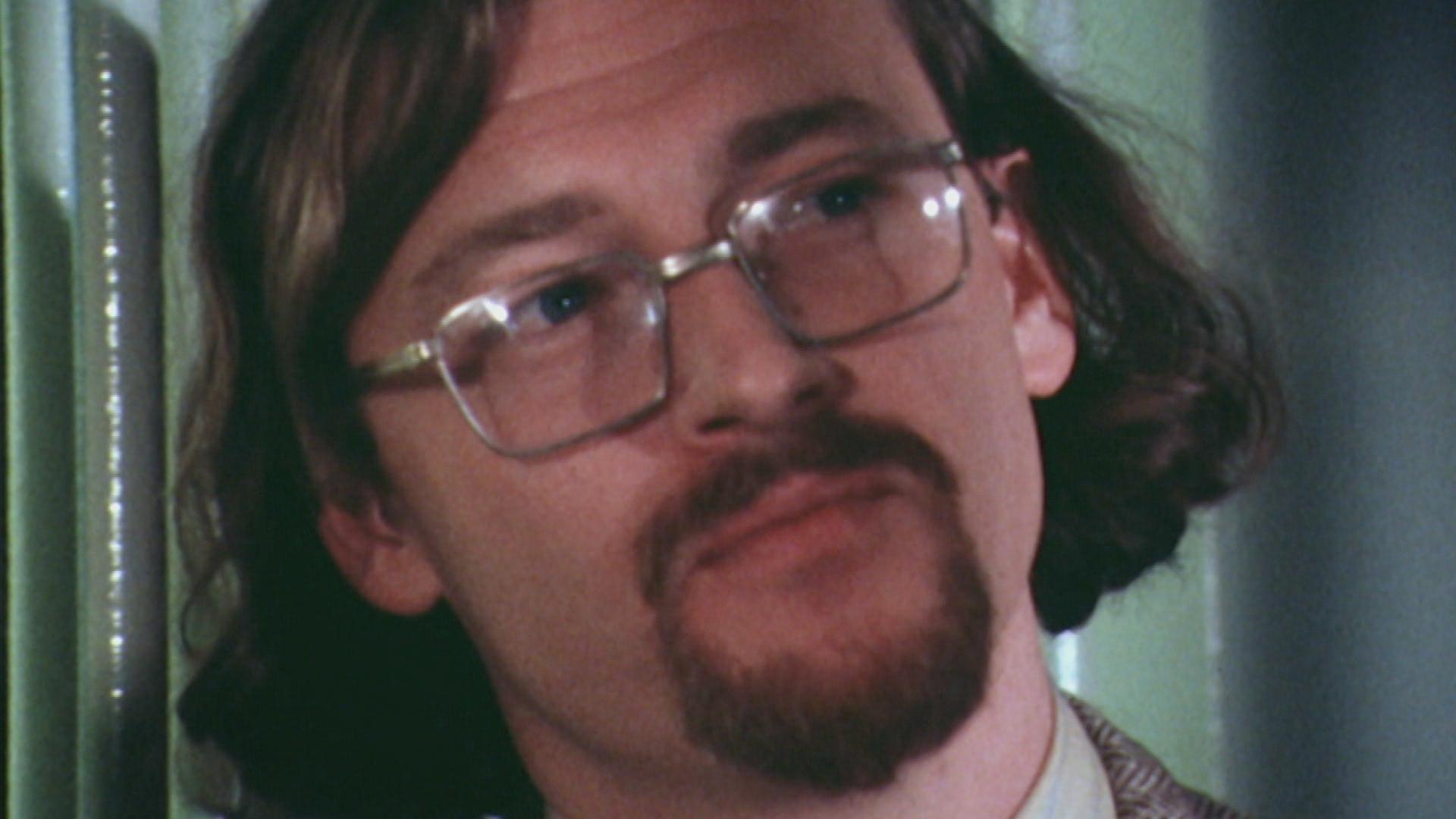

Dr. Elliott T. Barker had been inspired by the work of British psychiatrist Dr. Maxwell Jones, who had pioneered involving patients in mental hospitals in their own therapy. (CTV)

Barker arrived at his new job at Oak Ridge in 1965 with a novel plan of his own, one inspired in part by his travels. He would combine coercive techniques like truth serums and sensory deprivation with patient-led encounter groups to force psychopaths to confront their illnesses. It would be called the Social Therapy Unit.

“I think I was more idealistic than I am now,” Barker said in an interview recorded in 1993 and obtained by The Fifth Estate. “I thought we were developing the best program in the world and we really were going to fix psychopaths and these patients really were going to get better.”

One of the key components of the Barker plan was that patients would serve as therapists to each other. To an underfunded institution, it was an attractive solution to a rather ugly problem: there weren’t enough doctors on staff to treat prisoners.

But if the initial motivation had been to make a virtue out of necessity, Barker doubled down on his idea.

“I hired a patient when there were no staff around, a patient who could do superb mental statuses, better than I could, and he’d see each new admission and write up a beautiful mental status,” Barker said in 1993. “He was there for about six months until he ran off with the social worker’s wallet and credit cards and whatever.”

The prisoner-patients at Oak Ridge could order drug treatments for each other, including LSD, methamphetamine and truth serums. Alcohol treatments were another favourite. The men, some of them severe alcoholics, have said they would be forced to drink large quantities of high-proof alcohol. The goal wasn’t to treat their mental illness, but to weaken their defences and force them to examine their own shortcomings.

“The point of the whole program was to break us down mentally,” former Oak Ridge patient Jim Motherall said in 2016. “They believed if you could strip away all our bad defences that got us into trouble, they could rebuild us as better human beings.”

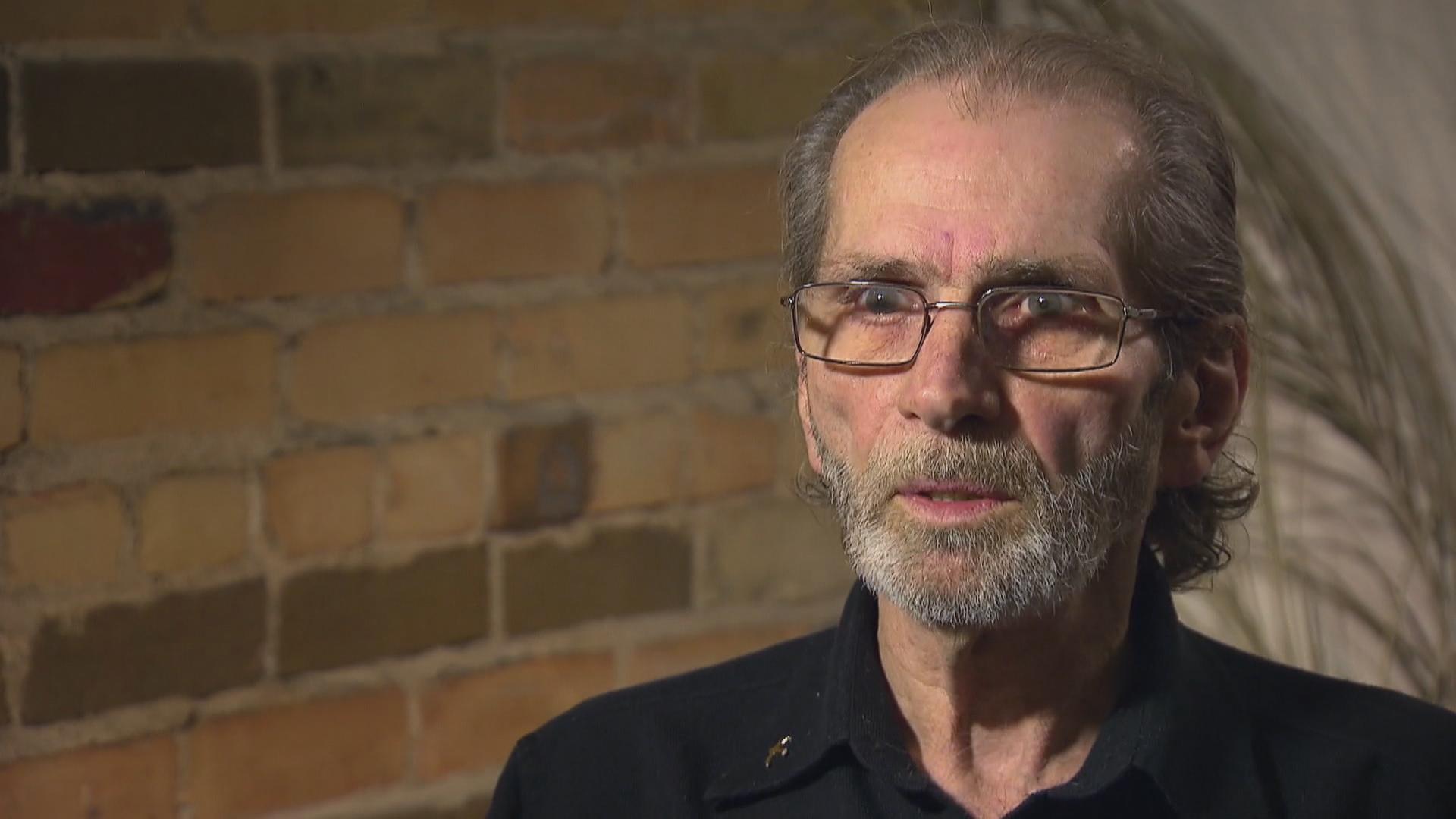

Jim Motherall, shown in in 2016, was sent to Oak Ridge in 1972 , where he was diagnosed as having a personality disorder and underwent numerous experimental drug treatments. He died in 2018. (Warren Kay)

Motherall was sent to Oak Ridge in 1972 after he attacked a 15-year-old girl with a tire iron, an offence he admitted was not his first, nor would it be his last. He was diagnosed as having a personality disorder and underwent numerous experimental drug treatments at Oak Ridge, including LSD and a hallucinogen called scopolamine.

“They gave you six shots a day of that stuff. By the end of the first day, you didn’t know who you were or what you were doing,” said Motherall. “You can’t do that to that many people over and over … and call it treatment because that’s the nice word people want to hear when the real word is torture. Cause that’s all it was beginning to end,” he said.

At the outset, Barker thought patients would take part willingly in the new programs, but that didn’t always happen. To ensure that even the most reluctant patients would submit to the “therapy,” Barker invented the Total Encounter Capsule.

Some say he cribbed the idea for the capsule from the U.S. military, but wherever the inspiration came from, the reality was stark.

The capsule was a windowless room with padded walls and no furniture except for an open toilet. Lights were left on 24/7 to remove all references to time and food was administered through a tube in the wall. Groups of prisoners, usually naked, would be locked in together for as long as 10 days at a time, their only task to confront one another about their mental flaws.

“It didn’t matter if you cried, there was no compassion, there was no recognizing you as a human being who’s had enough,” said former patient Allen McMann.

McMann is now homeless and living on the streets of Vancouver, but in the mid-1970s, he was a 16-year-old who’d tried to run away from a group home to escape abuse.

Allen McMann was a teenager when he was sent to Oak Ridge, where he was sexually abused there by an older patient. (Christian Amundson)

Authorities pegged him as a troublemaker and sent him off to live with the country’s most dangerous offenders in Oak Ridge.

He spent his 17th birthday in the capsule, where he was first celebrated and then punished by a patient who was a few decades older than him.

“They took toilet paper and they wrote Happy Birthday with it on the wall. And later that day … one of the guys wanted me to masturbate him,” he said. “I didn’t know what a pedophile was. When I went there, I was a virgin. I wasn’t the brightest kid on the block, I readily admit that.”

If the capsule was intended as therapy, then to the patients, the MAP program never seemed to be anything other than punishment. MAP stood for motivation, attitude and participation, or as it’s been called more recently by the patients themselves, torture.

“They would strap your legs together and then you’d be put on the floor, and you had to maintain a perfect T-square position,” said McMann. “You weren’t allowed to move unless you asked for permission, and asking for permission would be raising your finger for like two seconds and then putting it down. If you kept your finger up longer than that, they would accuse you of trying to garner favour from the teacher.”

Barker would later describe his role in day-to-day operations at Oak Ridge as not so much a doctor but as a sort of master puppeteer.

“My policy was to work with the key power players, the key attendants who had informal power and the key patients who had informal power and me, and I was like a politician negotiating,” he said in the 1993 interview. “I had total control.”

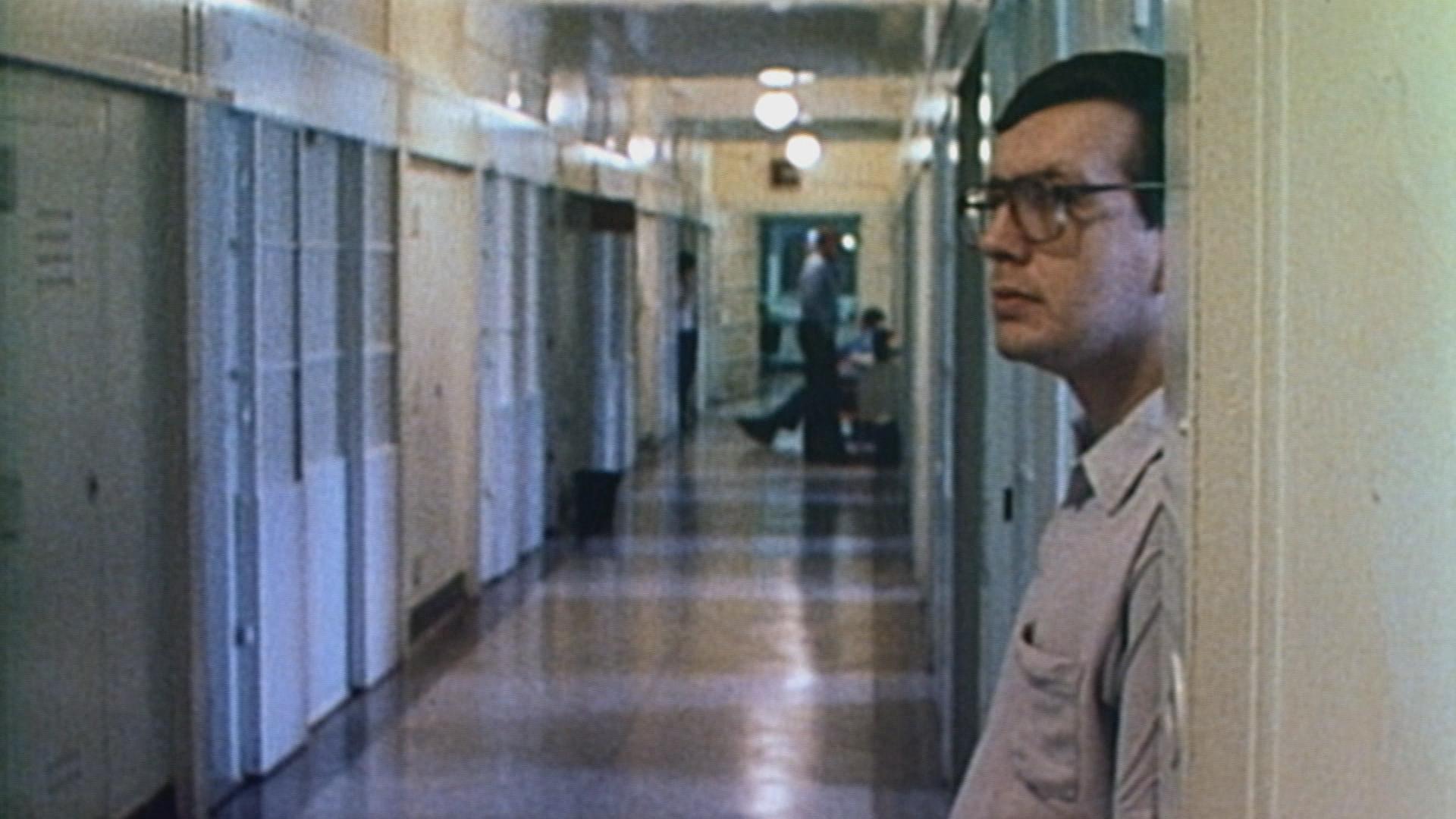

Many of the prisoners sent to Oak Ridge had been found not criminally responsible for crimes such as murder or rape. (CBC)

Looking back, it’s hard to imagine how the psychiatric community, let alone government authorities, could have viewed the Oak Ridge experiment as an exciting mental health initiative.

But when you look at the history of mental health hospitals, it becomes clear that change, almost any change, was seen as an improvement. Asylums, as they were known in the earlier 20th century, were desolate places where those with mental illnesses were warehoused and the focus was on controlling patients, not treating them.

Dr. John Deadman, a psychiatrist who was a contemporary of Barker’s, said even as recently as the 1950s, little was known about how to treat mental illness. Treatments for a diagnosis like mania were not only crude but cruel.

“The only way you could deal with a patient who was manic was to put them in a tub with continuously running water through the tub,” said Deadman.

“It had a canvas cover on it so they couldn’t get out, just their heads stuck out … and then you lowered the temperature of the water and they went into a state of hypothermia. That was the only treatment they had for mania at that time.”

Then the swinging ’60s came along. New ideas began to spread like contagion and the field of psychiatry was not immune.

At McGill University in Montreal, Dr. Ewan Cameron was conducting CIA-funded experiments on mind control and sensory deprivation. While the public didn’t know about it, some in the field of psychiatry did.

“At the time Elliott Barker was doing this, this was all new fresh stuff. And I don’t know exactly what his motivations were, but he really felt he was trying cutting-edge therapy,” said Deadman, who would later become medical director of the Whitby Psychiatric Hospital.

“I met him on a stag weekend … and I can remember he was really quite enthusiastic about all these things and perhaps not as critical as he should have been.”

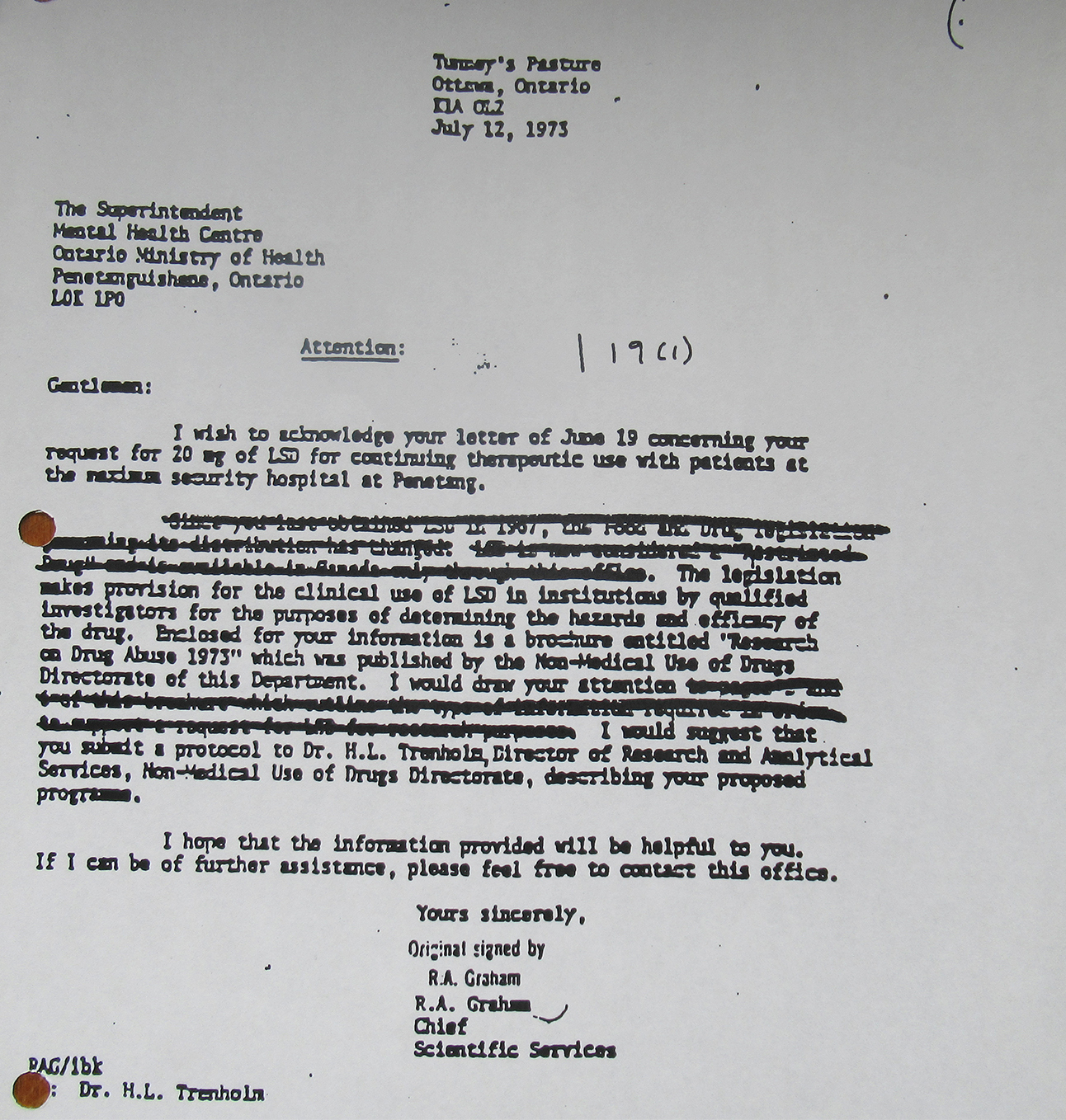

There’s no evidence that the programs at Oak Ridge were funded by the CIA. The federal Department of Health supplied Barker with LSD to conduct his experimental treatments. In the 1993 interview, Barker bristled at the idea that hallucinogens were forced on patients.

“God, the guys we had there were lining up for LSD. Everyone wanted it. It was the ’60s and we gave it in a responsible way,” he said.

The federal Department of Health controlled access to LSD for scientific research purposes in the 1970s. (Submitted by estate of William Brennan)

For a while, Barker was a darling of the psychiatric world, his programs praised by government officials, the media and other psychiatrists who frequently toured the Oak Ridge facility.

The superintendent of Oak Ridge, Dr. Barry Boyd, bragged about his young doctor’s successes to visiting officials.

But by the early 1970s, Barker himself began to doubt his treatments always worked.

“Boyd used to say to people: ‘Dr. Barker has a program that will cure people — next month. You know, by next month they’ll be cured.'” Barker said. But “by that time, guys had been out and [reoffended] and it was pretty clear that … guys were going out and getting into shit.”

By that time, he’d been working with psychopaths for about five years and his initial belief that he had come up with a way of curing them had been replaced with a new belief, one firmly rooted in reality and tinged with the bittersweet.

“You have to be burned by psychopaths a few times and survive it before you can like them and enjoy them and not be hurt by them,” Barker said.

“Psychopaths are marvellous at making you think that their world revolves around you…. And if you believe that and sort of bask in that glory and then … you find one day that they deal you off or stick a knife in your throat — not literally — that you mean nothing to them emotionally.”

Around 1971, Barker took a leave of absence from Oak Ridge and retreated to his farm just outside nearby Midland. He set up a private practice in town and from time to time, he served as an expert witness in court.

In the 1970s, when Canada was debating the abolition of the death penalty, Barker developed a new reputation — one he described as a “hanging psychiatrist.”

“There are guys who are so dangerous nobody is going to affect that,” he said. “It’s far better [rather] than curtailing parole, which is what they were doing, to hang a few people even though it was wrong. And you can pick out a few people who are absolutely dangerous and absolutely untreatable and hang them.”

WATCH: How Dr. Elliott T. Barker became known as the ‘hanging psychiatrist’:

But even though Barker now believed that the sickest of his patients could never be cured, the programs he’d developed for treating them continued at Oak Ridge under a new doctor, Gary J. Maier.

“Gary Maier was really out of the box, you know, he’s a kind of spiritual guy,” said Welsh-American author Jon Ronson, who interviewed him for his 2011 book The Psychopath Test. “He talked to me a lot about looking into people’s eyes and seeing their souls.”

Maier had recently graduated from medical school, was not a psychiatrist and did not have a background in forensic medicine. Two or three times a week, he’d pay a visit to Barker to discuss whatever issues came up. It became clear early on that Maier was quite different from Barker.

Dr. Gary J. Maier had just graduated from medical school when he took over from Barker at Oak Ridge. (BBC)

“I’m an agnostic psychiatrist — I don’t really believe a lot of psychiatry,” Barker said in the 1993 interview, “but he was a believer. But his fatal flaw was he didn’t recognize the politics of the situation and after a year, I went to Boyd and said: ‘Look, I want to stop supervising Gary. I think it’s not going to work. I think this guy is going to run afoul of the attendants.’ “

Barker’s prediction was correct. Ronson said Maier tried lots of what might now be considered new age therapies on his patients — things like chanting and dream analysis — but his favourite treatment was said to be LSD. He’d tried putting small groups of prisoners on acid trips, but one day decided to give LSD to the whole ward at once.

“That seemed to be a turning point,” said Ronson. “I think the guards were like ‘This is becoming a real safety risk now.’ And Gary Meier turned up one day to find that … his key didn’t work anymore, the locks had been changed and that was the end of the program.”

WATCH: How the program under Dr. Gary Maier ended:

Barker had been in and out of Oak Ridge since going into private practice, but now with Maier’s departure, he was lured back full time, at least for a year.

What his involvement was in the next evolution of the Oak Ridge experiment isn’t clear from the documents, but the programs he’d created had long since taken on a life of their own. And they were about to mutate.