COVID-19 origins conspiracy theories: constructive alternatives

Thanks to everyone who commented on my previous diaries regarding conspiracy theories surrounding the origins of COVID-19. This will be my last dairy for a while because it will take a fair amount of work to put together the next few dairies revisiting the development of these conspiracy theories during the pandemic. I’m tempted to say it’s not worth the effort, but I’m writing this up as much to get my own thoughts straight as for others, so I’ll probably have something together in the next month or two.

My tentative plans are to look at their development during three phases of the pandemic:

- Initial accusations against scientists and the backlash (Dec 2019 — mid 2020)*

- Backlash to the backlash (mid 2020 — mid 2022)

- ‘Stop the Steal’ adopts ‘lab leak’ (mid 2022 and on)**

In this diary, I want to highlight some of the legitimate claims involved in the ‘lab leak’ theories and some ideas on how to constructively address problems identified there. The main legitimate claims that I see are:

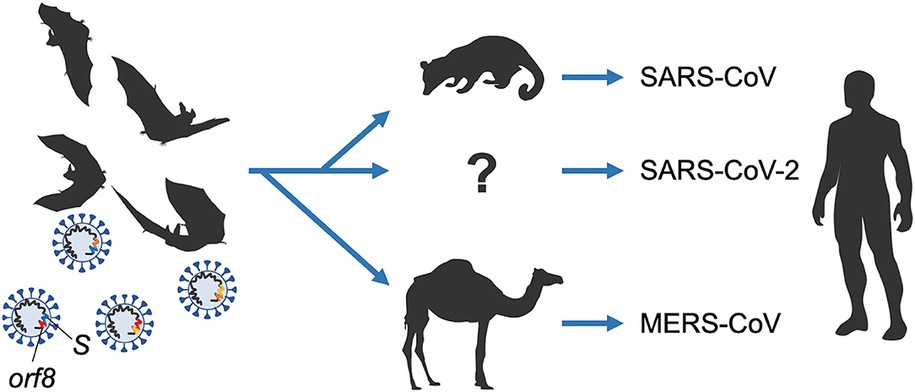

- The ‘zoonotic’ theory has gaps in it; specifically, scientists have not identified any virus population that could have been the immediate source of a zoonotic infection.

- Laboratory-acquired infections do happen, and they sometimes result in broader outbreaks.

- People hide embarrassing facts and try to deflect blame; the PRC and CCP have institutionalized this at a national scale with near-totalitarian thoroughness, but these problems exist in many other institutions as well.

These are all reasons to not rule out the possibility that the pandemic started with a laboratory acquired infection. However, these are not evidence for the ‘lab leak’ origin theory. As far as I’m aware, the claims that actually favor ‘lab leak’ are just rumors and pseudoscience — the raw material of manufactured outrage (I’ll get into those in future diaries).

The failure of our country to learn lessons from discussions of COVID-19 origins is just part of a much broader failure to examine missteps made during the early pandemic. As of now, the only level-headed review that I’ve seen comes from the self-appointed “COVID crisis group” in their book, “Lessons from the COVID War”. Of course, any possibility of non-partisan reports coming from the federal government was made nearly impossible by Trump’s coup plot in late 2020, and the GOP’s subsequent decision to rationalize and excuse those actions.

I’d say there’s lots of blame to go around, but blame is largely unproductive. Honest mistakes need to be owned and corrected at a institutional level; only abuses of power or misconduct should be punished. ‘Lab leak’ conspiracy theory propaganda has been fully mainstreamed over the past year or two, and much of it is little more than efforts to place blame on political opponents by quote-mining seemingly incriminating statements from hacked or FOIA’d documents.

Before getting into ideas of how to address the problems identified above, I think we need to acknowledge some basic facts and principles:

- The USA and allies cannot dictate China’s biosecurity policies or research priorities. If we want to influence activities in China, we need their cooperation and trust. We can share expertise and provide incentives to them to develop their biosecurity capabilities. Along these lines, we should recognize that US NIH funding of research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology had only a small impact what they researched and how.

- The USA and allies cannot perform a proper, independent investigation within China. The PRC would not trust us to perform such an investigation, and no amount of haranguing and defamation will change that.

- Being ‘Chinese-linked’ (i.e. Chinese), is not discrediting.

- Both zoonotic and laboratory-acquired infections pose a risk of outbreaks and pandemics. We knew this before COVID-19, and this big-picture fact will remain true regardless of anything we learn about the origin of COVID-19. Nailing down the origin of COVID-19 will provide a more detailed understanding of the risks.

- Scientific publishing, even peer-reviewed publishing, is rather open and very difficult to censor — in addition to the preprint servers, there are plenty of different publishers spread out across the world, some of which (e.g. MDPI) tend to go very easy on the authors.

- Real science involves clear claims and a process of back-and-forth among disagreeing scientists in order to identify and close gaps in their theories. Real science produces reviews of theories to clearly show which claims are still viable and what gaps exist. This gives skeptics a clear argument to criticize; in contrast, pseudoscience relies on dumping piles of unorganized ‘evidence’ in front of the audience and refusing to clearly describe a favored theory. Pseudoscience relies on confusing the audience with the sheer number of claims, without doing the work to organize those claims into a coherent theory that would clearly show what evidence is relevant and what evidence supports separate and mutually exclusive theories (e.g. COVID-19 originating at Wuhan CDC as opposed to Wuhan Institute of Virology) .

- A theory is not justified by the fact that opponents eagerly dismiss it or even withhold information that could be relevant (though these can be a problem in their own right). Denials are not evidence of a cover-up. Even angry denials are not evidence of a cover-up; in fact, they are expected when a person is slandered and threatened. Conflicts of interest are not cover ups; failures to recuse oneself or disclose relevant conflicts of interest can undermine credibility, but they are only misconduct when the ‘conflict of interest’ requirements are standard practices, not the ad hoc and excessively broad demands of conspiracy theorists.

- WHO is not a neutral or objective arbiter — like the UN, it is completely dependent on cooperation of member states. The UN is great for facilitating diplomacy and coordinating action on shared interests, but is incapable of rising above the failings of its members, which include many tyrannical governments.

With that said, how can we address the issues raised above? Given the current public awareness of these problems, we have an opportunity to move forward on addressing them.

- To identify and control the risk of zoonotic infection, we need surveillance of diseases and pathogens among any animals that humans regularly have contact with (both livestock and wildlife). This will be expensive. Much of this surveillance can be worked into agricultural services, but if we want it to be global, we will have to help other countries develop their programs. China is able to do this for themselves (and they are well aware of the risks of not doing so), so maybe the only incentive we can provide for them is to race for prestige by supporting capacity building in less wealthy countries. Controlling the risk of zoonotic infection may require restrictions or even bans on certain types of livestock — such as the mink industry that hosted many COVID-19 outbreaks and have also recently hosted flu outbreaks.

- To reduce and isolate any laboratory-acquired infections, we need improved biosafety procedures and regulations. Again, this is expensive. We also can’t impose them on China. It may be tempting to say that we should just ban any dangerous research, but it would be counterproductive to prevent researchers from performing activities that other people regularly perform (e.g. visit bat-filled cave, capture bats) or studying phenomena that are known to occur in nature near humans (e.g. genetic recombination among coronaviruses in those bats).

- The broadest problem in the list is how to effectively assess the credibility of information we receive and how to assure that our institutions behave credibly even in the face of potentially embarrassing information. Some ideas are below, but this will not have a simple answer.

- Information from countries without press freedom will always have lower credibility. We all need methods to independently confirm such information, while not developing a general distrust and fear of people from those countries (or have relations in that country that expose them to leverage).

- We need strategies to identify and resist influence campaigns from hostile foreign countries. The PRC is an especially big concern given their growing wealth and increasing business relationships, causing some to self-censor as the price of doing business with China.

- Similarly, we need to identify and resist influence campaigns organized domestically — we face a constant stream of multi-million dollar propaganda campaigns funded by dark money.

- We need greater transparency and independence in science and journalism. Scientists have made great efforts to modernize scientific publishing over the past couple of decades, though arguably there’s still a lot to do. During that same period, journalism has become increasing consolidated, requiring us to be more conscious in our support of independent media.

- We need more transparency and clear ethical expectations in government, including state and local government.

- I think many scientists and science journalists jumped to conclusions and were overly defensive when faced with suspicions about a laboratory origin of the pandemic. They apparently felt the need to overstate their certainty in hopes that it could shut down conspiracy theories. I think it backfired. I don’t know how to avoid this in the future. Most scientists are not experienced in dealing with politically charged topics or being in the spotlight, but they also are not willing to sit back and let politicians lead the discussion about their research or their colleagues.

Finally, I have a few more general thoughts about how to move forward.

- Our journalists and publishers need better strategies for identifying smear campaigns (including conspiracy theories) and avoid lending credibility to them. I think this can be very difficult in a fast-paced field where information comes from many different sources and there isn’t always time to check into a source’s background or even think too critically about how they are spinning information. This may be related to reporters’ struggle to effectively cover outrageous candidates like Trump in 2016, or likewise to not portray powerful people as inherently credible.

- Activists need to avoid campism and realize that the enemy of my enemy is not my friend — too many supposedly liberal people have been working with authoritarians in the hope of getting a platform for whatever their pet project is — whether this is Jill Stein (Greens) hobnobbing with Vladimir Putin, or Jamie Metzl and other ‘liberals’ and advocates for a UN-regulated global biosecurity regime who happily cooperated with ‘Stop the Steal’ Republicans to harass scientists who disagreed with them.

- Scientific review drastically weakened during the pandemic — this allowed information to be shared more quickly, but also contributed to politicization where results would be pitched to the mainstream media before addressing fatal weaknesses identified by experienced scientists and sometimes even before releasing a full scientific report. This trend has been building for many years, but scientists and journalists still need to find a system that allows results to be communicated quickly, with peer review, but without gatekeeping.

I think many of these topics relate to general ‘security’ concepts, so I’ll point out that the Federal Government has a ‘Security Awareness Hub’ with self-paced teaching material to identify things like counterintelligence awareness and insider threat awareness.

* I know very little about the lab leak conspiracy theories circulating within China, and would appreciate any pointers to more information. I am aware of the PRC’s efforts to deflect blame to foreign actors.

** I know that MAGA Republicans promoted lab-leak conspiracy theories from the beginning, but I think they fully embraced it and became central to the campaign in 2022-2023.

Header image credit: Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses

Edit: Clean up some typos and redundancy.