Out There | Joe Bucciero

The earliest work in Guardian, an exhibition at Tara Downs of seven paintings by Budd Hopkins, is a small abstract tondo, a circular canvas with tracks of off-white paint rising from the surface and bleeding onto a thin frame. Hopkins made it in 1963, six years before the show’s next painting; it at once looks forward to his future output and remains something of an anomaly. Circles reappear, at least in part, in all the other works on view, but each of them is what the critic Michael Fried would call a depicted shape—painted on a larger, typically rectangular surface—and not the literal shape of the canvas.

In 1973 the curator April Kingsley, then married to Hopkins, wrote that the circle was his “personal image.” It was, she argued, like Rothko’s rectangle or, one could add, Jung’s mandala, both an ordering device and the sort of emblem one might see in dreams or visions. In the late 1950s Jung speculated that the postwar glut of UFO sightings in the West—reports of objects with “round shape, disk-like or spherical, glowing or shining fierily in different colors”—was to be understood as a popular search for mandalas, for signs of stability in the face of “technological fantasy” and possible apocalypse. It can be tempting to look at Hopkins’s circles in a similar light, which makes it tempting, too, to see the oblong splotch of black and yellow in the middle of Untitled Tondo as a flying saucer whizzing across the canvas.

Such a reading would have been anathema in Hopkins’s milieu at the time. This was downtown New York in the early 1960s, a scene under the influence of formalist critics like Fried and, even more, his mentor Clement Greenberg, who proposed that abstract paintings referred only to their own artistic properties. Fried’s friend Frank Stella—whose later work Hopkins praised in Artforum in 1976—put his own antipictorial ethos plainly: “What you see is what you see.” But outside this milieu, plenty of people still wanted to see something else in abstract art. A 1959 Life magazine article pictured the Metropolitan Museum’s director, James Rorimer, inspecting a Pollock painting with the headline, “Baffling U.S. Art—What It Is About.”

Some other midcentury theorists—those disposed to psychoanalysis, the counterculture, or both—treated abstraction as a conduit for various kinds of individual revelation. Jung, for his part, devoted a chapter of his book on flying saucers to UFOs in modern art. He argued that abstract paintings were something like Rorschach tests:

Modern art is less concerned with the pictures it produces than with the observer and his involuntary reactions. He peers at the colours on the canvas, his interest is aroused, but all he can discover is a product that defies human understanding. He feels disappointed, and already he is thrown back on a subjective reaction which vents itself in all sorts of exclamations.

What you saw in a work of art was not only what you saw but also something else, maybe something deep inside yourself—or maybe nothing at all.

The temptation to see a flying saucer in Untitled Tondo stems from more than just the postwar vogue for UFOs. As if summoned by the painting, in the summer of 1964 Hopkins saw a “small, lens-shaped object in the sky” in Truro, Cape Cod, where, having enjoyed some success in New York, he had recently built a studio. He reported the sighting to the National Guard; he told sympathetic friends, including Richard Hofstadter; he immersed himself in a growing body of UFO literature over the next decade and then began to contribute to it himself.

“For years I insisted that the 1964 UFO sighting had no lasting effect on my work,” Hopkins wrote in his 2009 memoir, Art, Life and UFOs. But then he realized that, after that year, he had “used the circle as both an imperious, controlling solid and as a mysterious void.” Like abstract paintings, UFOs prompt their viewers to search for meaning within familiar but untethered forms. Untitled Tondo preceded Hopkins’s sighting by a year, but UFOs were already in the air (the Air Force fielded 399 sighting reports in 1963). As the rest of Guardian shows, linking his art to his growing interest in ufology is both reasonable and overdetermined, clarifying and confounding, not unlike the work itself.

*

Hopkins was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1931, and began drawing as a toddler stricken with polio. He went to Oberlin, where he took art history classes and in 1952 attended visiting lectures by Robert Motherwell. To the young Hopkins, abstract expressionism “became a magnet, a goal.” It suggested to him that art’s content was “the painter’s own life and joys and restless discontents.” After graduation, he moved to New York and befriended several of the artists whose work drew him there: de Kooning, Rothko, Kline.

By the mid-1950s he was following those painters’ models—wild brushwork, muddy color—while also trying to strike out in his own direction. “It was as if memories of the West Virginia hills…were still present in my head,” he recalled in the memoir, “expressed now with some of the energy and daily velocity of New York City.” Soon he adopted a new compositional method based on preparatory paper collages and traded his formless agglomerations for hard lines, vivid colors, and layered shapes. In 1963 he was featured in the Whitney Annual and had a solo exhibition at Poindexter Gallery, which Brian O’Doherty, writing in The New York Times, called “one of the year’s best.”

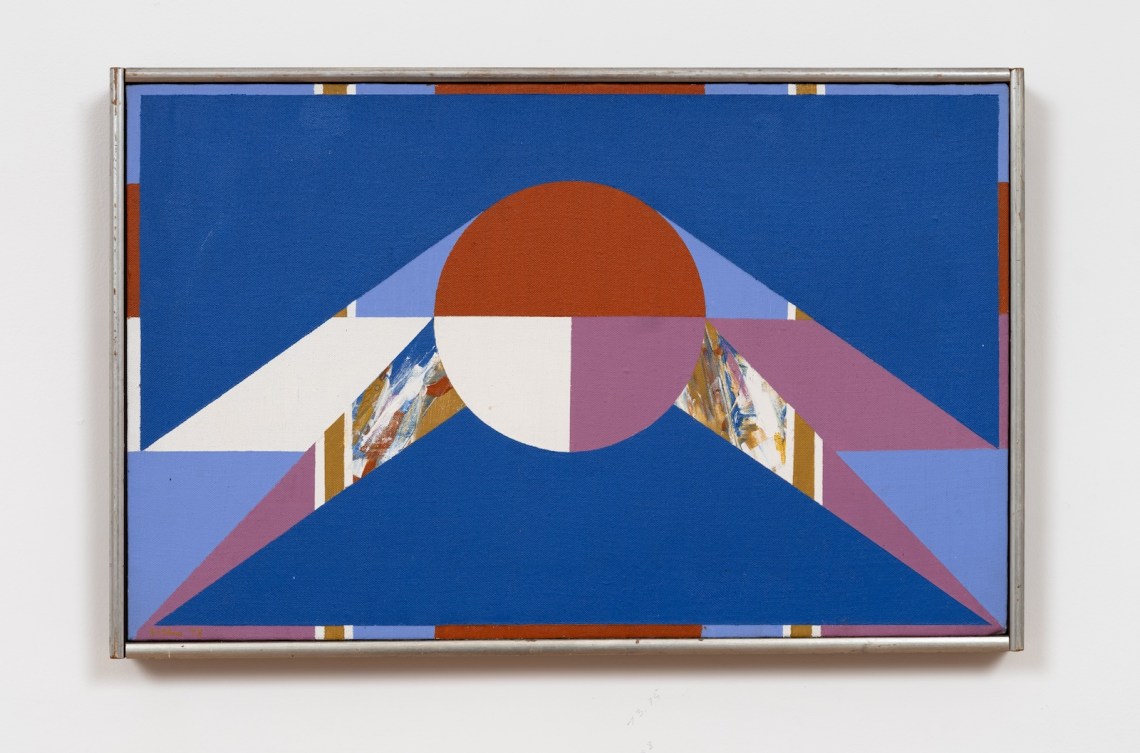

The next painting chronologically in Guardian is also the largest, the nearly seven-foot-high Tropaz (1969). Light and precise, it positions Hopkins among a loose cadre of post–abstract expressionist artists who retained the earlier movement’s energy but rationalized its forms. (Al Held, Deborah Remington, and William T. Williams were others; in a way, so was Stella.) In Tropaz a green-haloed purple circle sits atop cascading triangles. Some triangles are solid-colored, some are striped, like a Kenneth Noland painting in miniature. One of them relies on a trick Hopkins often played: it contains a clutter of wispy marks, as if there were an abstract expressionist canvas underneath the finished painting. Further conjuring this illusion of layers, the triangle’s green ground peeks from around the circle as well as from the canvas’s side edges. For all their apparent regularity, in other words, Hopkins’s shapes do not always behave rationally. Many of them cut in and out, over and back, making an otherwise flat canvas start to pulse.1

In a short essay called “Martians,” Roland Barthes argued that UFO sightings had a transportive, even utopian, allure. A semiotician, he described that allure in formal terms. The “roundness” and “smoothness” of the craft—“a substance without seams”—throws into relief the “irregular planes” and “discontinuity” of real life, with its nuclear proliferation, government secrets, and media noise. Similarly, in Tropaz an angular mess reinforces the “roundness” of the unmodulated circle that rises above it. Unlike, say, Mondrian, whose influence he often cited, Hopkins insisted that after 1964 he composed his paintings hierarchically, hierarchy being an “anthropomorphic” principle: “the way we perceive the world.” Positioned above-center, where the head might be in a portrait, the circle in Tropaz conjures the mind and its ability to organize abstract information.

Hopkins’s paintings of the early to mid-1970s synthesized what, in Tropaz, appears opposed. Hiram (1973) and Scorpio Series (Scorpius Constellation) (circa 1970s) retain the earlier painting’s sharp lines, contrasting color, and intimation of layers, but they destabilize the circle, rending it with other forms without obscuring its outline. Scorpio’s spacey title suits its 2001-esque composition: a white middle ground and a diagrammatic circle with an indeterminate relation to its surroundings. City Slant (1974), one of Hopkins’s “assembled” paintings, makes this fragmentation literal. It consists of four separate, connected canvases, one with a multihued circle, two cut by diagonal lines, and one that looks like a zoomed-in charcoal drawing, or perhaps a nebula.

*

By the mid-1970s Hopkins had been staging solo shows in New York and Provincetown almost annually; in 1976 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He started writing, too, and published several pieces in Artforum: on the photographer Barbara Jo Revelle, whose “radical disjunctions” he admired; on Richard Diebenkorn, in whose abstract paintings Hopkins perceived “ghostly curves” and “half-glimpsed heads”; and on Franz Kline, praising his late friend’s architectonic forms and overlooked facility with color.

One could read Hopkins’s criticism as a kind of self-assessment. His art likewise dealt in construction and partition, in surprising color and spectral associations. In 1975, also in Artforum, Roberta Smith argued that he hewed too closely to his predecessors and peers. “Hopkins is merely combining other people’s styles without adding enough of himself,” she wrote. “It’s pastiche.” Hopkins might have countered that what he called his “collage aesthetic” was intentional, a technique meant to channel “the disjunctions of our typical life experience.” Rather than pastiche, he seems to have perceived his work as regenerative, a project of taking modernism apart and reconstituting it for the new age.

The two most recent works in Guardian come from a series of the same name that Hopkins began in the late 1970s. Both trade the circle for the semicircle. In Guardian (1981), that form’s black outline intersects a mess of solid and brushy lines, also black, all situated against a white ground, in a distorted echo of Malevich, another Hopkins touchstone. Guardian XV (1980) is painted on shaped wood; like Stella in the mid-1960s, Hopkins forms his geometry using both literal edges and painterly depiction. Here he gives pride of place to a semicircle that appears to stand in front of the other shapes. In an artist’s book from 1983, which pairs photographs of his shaped-wood paintings with the Met’s Assyrian reliefs, he personified the Guardian as a “figure…who protects the hallowed space.”

Hopkins now conceived art as a transcendental outlet, a way for him to “fly,” to ask unresolved questions. But even as he embraced his “mystical side,” he also wanted to exercise his “rational, scientific side”—to find answers. His chosen outlet was ufology, especially the study of visitations. In 1976 he wrote a piece on the topic for the Village Voice (syndicated in Cosmopolitan under the headline “UFOs: Would You Believe One If You Saw One?”). Five years later he published a book, Missing Time, that theorized why people cannot remember their alleged abductions; soon he was hypnotizing abductees to surface those often unpleasant memories, many of them involving sexual abuse. It’s a practice that some critics have deemed therapeutic and others exploitative.

Either way, Hopkins became a ufological authority, working on his own and in collaboration with credentialed adherents like the Harvard psychiatrist John Mack and the Temple historian David Jacobs. Hopkins’s follow-up to Missing Time, Intruders, was a best seller, later adapted into a documentary and a miniseries. He was also subject to criticism, including in these pages, where in 1978 Martin Gardner chided him for “verbal obfuscation” and, ten years later, blasted Intruders as “preposterous.” In 1998 Frederick Crews described Hopkins and his cohort as opportunistic and charged them with “indifference to extant empirical critiques” of ufology. Similar criticism has met the work of Hopkins’s late-in-life partner, Leslie Kean, who in 2017 cowrote a New York Times story on the Pentagon’s UFO program that has since been credited with helping to reignite congressional interest in the phenomenon.

*

With its oversized “head,” Guardian XV resembles the image of an alien—bulbous face, thin figure—codified in the popular imagination by the cover of Whitley Strieber’s 1987 book Communion, on which Hopkins consulted.2 But it is not, in the end, an extraterrestrial portrait. It is a grouping of shapes and colors—painted marks on wood. Postwar US art is replete with depicted UFOs: artists like Joseph Yoakum, Ching Ho Cheng, and Jim Shaw, to name a few, all transferred saucer images to canvas or paper. In their work the saucer can both evoke humankind’s fragility and promise a way out, toward freedom. There are no such icons in Hopkins’s art.

If his parallel practices ever intersected, it was along formal rather than literal lines. In 1977 the curator Carter Ratcliff found Hopkins’s art “both clear and ambiguous. Rather, it is clear about ambiguity.” Two years earlier, in A Theory of Semiotics, Umberto Eco had called ambiguity “a sort of introduction to the aesthetic experience…instead of producing pure disorder, it focuses my attention and urges me to an interpretive effort.” For some people, UFO sightings have a comparable effect, posing ambiguous questions that can lead to a sense of liberation, however escapist or selective. At his best, Hopkins paints this possibility, makes you wonder for a moment what you saw.