Solar geoengineering and the chemtrails conspiracy on social media – Humanities and Social Sciences Communications

Abstract

Discourse on social media of solar geoengineering has been rapidly increasing over the past decade, in line with increased attention by the scientific community and low but increasing awareness among the general public. The topic has also found increased attention online. But unlike scientific discourse, a majority of online discussion focuses on the so-called chemtrails conspiracy theory, the widely debunked idea that airplanes are spraying a toxic mix of chemicals through contrails, with supposed goals ranging from weather to mind control. This paper presents the results of a nationally representative 1000-subject poll part of the 36,000-subject 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), and an analysis of the universe of social media mentions of geoengineering. The former shows ~ 10% of Americans declaring the chemtrails conspiracy as “completely” and a further ~ 20–30% as “somewhat” true, with no apparent difference by party affiliation or strength of partisanship. Conspiratorial views have accounted for ~ 60% of geoengineering discourse on social media over the past decade. Of that, Twitter has accounted for >90%, compared to ~ 75% of total geoengineering mentions. Further affinity analysis reveals a broad online community of conspiracy. Anonymity of social media appears to help its spread, so does the general ease of spreading unverified or outright false information. Online behavior has important real-world reverberations, with implications for climate science communication and policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The story goes like this: tens of thousands of commercial airliners a day are deliberately spraying some kind of mixture of toxic chemicals—either across the United States, or possibly globally—in what would amount to one of the largest covert operations ever. The scheme has been going on for years, perhaps decades (Thomas, 1999). The goal: everything from large-scale weather modification to mass population or mind control. The motive presumably would vary with the goal, but it is typically seen as a version of powerful business, government, and military interests covering up even worse deeds.

Except none of this is true.

“Chemtrails” are not real. The US Environmental Protection Agency says so (EPA, 2000). Scientists say so (Cairns, 2016; Shearer et al., 2016). An increasing number of investigative journalistic accounts say so (e.g., Dunne, 2017; Streep, 2008). Contrails, made up of water vapor, have been a byproduct of aviation ever since humans began to fly using jet engines (Pretor-Pinney and Sanderson, 2006).

An online essay (Thomas, 1999) might have been the first piece of writing connecting contrails to chemical spraying, even if it did not use the term “chemtrails”. Thomas (1999) references a 1996 Air Force paper on proposals to engage in weather modification (House et al., 1996). Together with the High frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP), House et al. (1996) helped fuel speculation of military links among conspiracy theorists (Newitz and Steiner, 2014; Streep, 2008), leading to online commentary under titles like: “Military Industrial Complex Takes Charge, Blasts Skies With Chemtrails”.

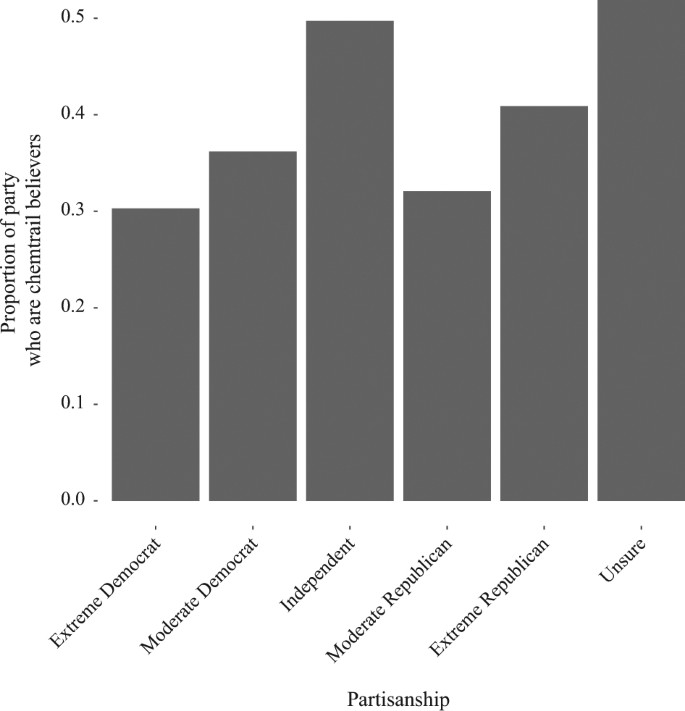

Meanwhile, the chemtrails conspiracy is no longer small. Per Public Policy Polling (2013), 5% of US respondents subscribed to the chemtrails conspiracy theory in 2013, next to a number of other conspiracies. Mercer et al. (2011) finds 2.6% “completely” and 14% “partly” believed in the conspiracy in 2010. Our representative pre-election survey of US adults conducted in October–November 2016 as part of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), shows around 10% describe the chemtrails conspiracy as “completely true” (Table 1, see Methods below). Roughly a further 20 to 30% describe it as “somewhat true”. Belief in the conspiracy spans the political spectrum, with no significant difference on either the left or right, or by strength in ideological affiliation (Fig. 1). The slightly higher belief in the chemtrails conspiracy among independents than among those on either side of the ideological spectrum is not statistically significant.

Both the sentiments expressed in the wider geoengineering discourse online and the chemtrails conspiracy demonstrate the importance of “echo chambers” (Vicario et al., 2016) created by social media in what amounts to a broad ‘community of conspiracy’. It also has potentially important linkages to wider political forces (Gainous and Wagner, 2014). While conspiracy theories have had a long history in US popular imagination and politics (Andersen, 2017; Barkun, 2013, Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009), the rise and election of President Donald Trump, in particular, has pulled discussion of conspiracy theories into the mainstream, with varying implications (Goertzel, 1994; Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009). While the CCES numbers show no correlation with extreme partisan political views (Fig. 1), our subsequent analysis of online social media discourse reveals how those propagating the chemtrails conspiracy theory online also engage in various other forms of extremist and conspiratorial discussions, ranging from affinities toward the views of Alex Jones on the one hand and toward terms like “Wikileaks” and “Benghazi” on the other. Meanwhile, representative tweets around the time of Trump’s election in November 2016 showed that some conspirators considered Trump’s election an opportunity to “expose” the chemtrails conspiracy, though opinions soon shifted, leading to online commentary such as: “Trump Admin to Increase Atmospheric Geoengineering Efforts, Spray Chemtrails for Next 100 Years Straight”.Footnote 1

Methods

US public opinion

Table 1 and Fig. 1 presented above are based on survey data collected via the CCES of the US electorate, which was conducted in October and November 2016 by YouGov/Polimetrix (YP). Administered online, it gathered a nationally stratified sample of more than 36,000 respondents. The “chemtrails” question was part of one of eighteen additional 1,000-subject pre-election studies. It came at the end of a 20-minute survey, with the latter 10 min focused on solar geoengineering.Footnote 2 Prior questions, thus, increased familiarity with solar geoengineering beyond the general public. Mahajan et al. (2017) analyzes the CCES results more broadly and provides information on general attitudes toward solar geoengineering use and research.

Online social media discourse

We use the social media analysis platform Crimson Hexagon to analyze the totality of English tweets for the decade from May 2008 through May 2017, in addition to mentions in public posts on Facebook, YouTube, Google Plus, Tumblr, and other blogs, online forums, reviews, comments, and news items. Twitter comprises the majority (77%) of the over 5 million relevant English posts, far ahead of Tumblr (4%), Facebook (3%), YouTube (3%), and Google Plus (<1%). Crimson Hexagon employs both a supervised learning method (Hopkins and King, 2010) and automated sentiment analysis of relevant online discourse on geoengineering.

“Relevant” posts include all public English posts mentioning at least one of eleven terms: “climate engineering” and “geoengineering” broadly; “solar geoengineering,” “solar radiation management” and its prominent abbreviation “SRM”, and “albedo modification” more specifically; “stratospheric aerosol injection”, “marine cloud brightening”, and “cirrus cloud thinning” as the three most promising and most commonly discussed methodologies; and, lastly, “chemtrails” and “HAARP” to zero in on the most commonly used terms in conjunction with the chemtrails conspiracy theory. We did not explicitly include word fragments or common misspellings, as Crimson Hexagon’s ‘guided’ categorization algorithm accounts for partial word mentions and detects misspellings.

Crimson Hexagon’s most significant advantage is its ‘‘guided’’ but otherwise automatic categorization of public posts into pre-determined categories (Hopkins and King, 2010). We chose five such categories, training the algorithm to categorize posts found via the eleven search terms into one of five groups: neutral science reporting (“neutral”); posts emphasizing unintended consequences and otherwise portraying geoengineering in a negative light without being conspiratorial (“negative”); posts emphasizing the potential positive impact and otherwise portraying geoengineering in a positive light (“positive”); posts espousing or otherwise helping to spread the chemtrails conspiracy (“chemtrails”); and off-topic posts, despite their mentioning one of the eleven keywords (“off-topic”). We trained posts to each category that had any presence in the data, and then used the built-in ReadMe algorithm to estimate the population proportions belonging to each category on the universe of posts fitting the keyword criterion.

A limitation of Crimson Hexagon’s Facebook data is the exclusive focus on public posts, missing “echo chambers” (Vicario et al., 2016) created in private online conversations among Facebook ‘friends’. On Twitter, Crimson Hexagon attempts to filter out bots, though some may well be included in the final analysis.

The sentiment analysis presented below takes advantage of Crimson Hexagon’s automated sentiment analysis, capturing “positive,” “negative,” and “neutral” attitudes toward a particular topic. The algorithm is able to pick up on sentiments conveyed in a post to categorize them, going well beyond mere keyword searches. For example, a tweet on 16 August 2016, saying “Expert consensus: Chemtrails aren’t actually a thing” is correctly categorized as science reporting, while a tweet saying “#Chemtrails Caldeira comes clean on chemtrails” is correctly categorized as chemtrails conspiracy. Some others are difficult to judge. For example, Crimson Hexagon categorizes a tweet saying “#Cloudseeding long-term, would negatively impact ecosystems left thirsty” as negative portrayal. Further inspection could also indicate it should be in the chemtrails conspiracy category, though either category might fit. Examples of off-topic mentions include tweets that use “SRM” in an entirely different context, for example, as abbreviation for “supplier relationship management”. Crimson Hexagon categorizes those correctly as off-topic.

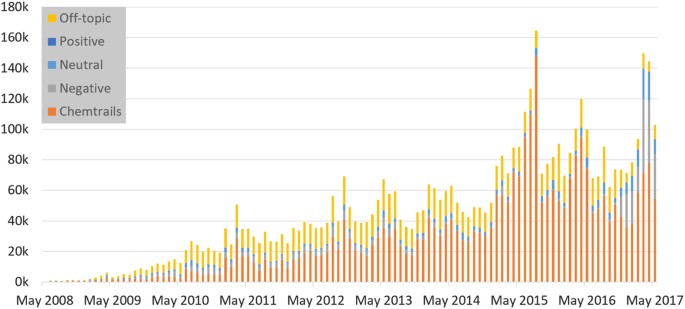

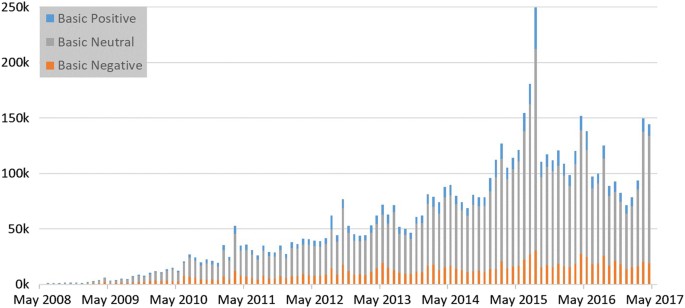

Monthly geoengineering monitor categories on Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms, May 2008–17, using Crimson Hexagon’s supervised learning methods (Hopkins and King, 2010) to categorize social media discourse as “chemtrails” (61% of total), ”negative” (8%), “neutral” science reporting (6%), “positive” (<1%), and off-topic (25%)

Findings

The vast majority of social media posts falls into the chemtrails conspiracy camp (61%), neutral science reporting is in the clear minority (6%), slightly trumped by negative portrayal (8%), with 25% of posts being off-topic. Positive portrayal barely registered at <1% (Fig. 2).

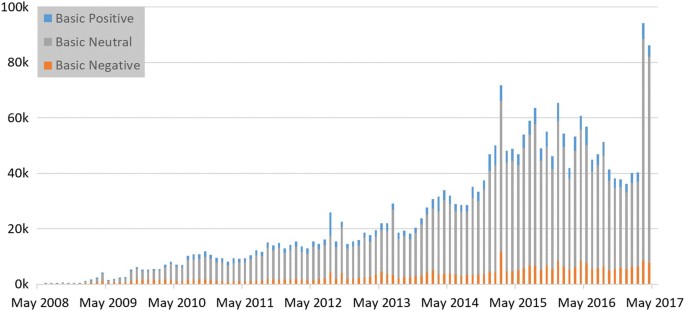

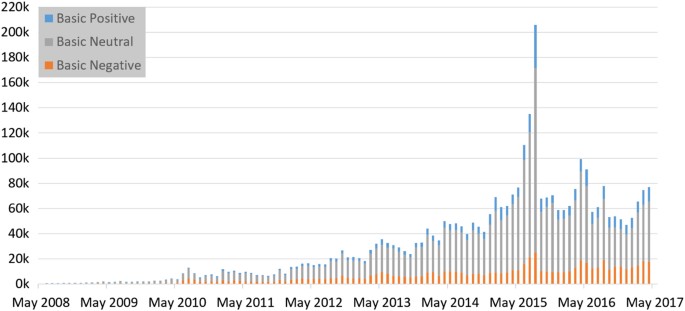

Automated sentiment analysis classifies social media mentions of geoengineering into positive, negative, and neutral categories. Figure 3 shows all social media mentions of geoengineering and assorted search terms by month from May 2008 through May 2017, including mentions of chemtrails. Figure 4 excludes chemtrails mentions. Both figures reveal a general upward trend, heavily influenced by single events. January 2015 saw the publication of the US National Academy of Science’s comprehensive set of reports on carbon and solar geoengineering (NRC, 2015a, b), leading to a spike of online discourse with and without the conspiracy theory. Similarly, the spike in April and May 2017 can be linked to the formal launch of Harvard’s Solar Geoengineering Research Program and associated media mentions (e.g., Gertner, 2017; Greenfieldboyce, 2017; Porter, 2017).Footnote 3

The proportion of non-chemtrails conspiracy social media mentions from May 2008 through May 2017 (Fig. 4) among total mentions (Fig. 3) shows no discernible trend. The ratio ranges from 18%, in March 2011, to 70%, in September 2009, with an absolute-value t-statistic of 0.61 when testing the H

0 of whether the slope of the trend line was statistically significantly different from zero. It is not. The chemtrails conspiracy appears to grow hand-in-hand with the general increase in social media discourse around geoengineering.

We compare the results between all geoengineering-focused posts (Fig. 3) to those without chemtrails (Fig. 4) instead of focusing on a chemtrails-only monitor (Fig. 5). The latter would skew results, as it excludes geoengineering posts not mentioning “chemtrails” that Crimson Hexagon’s learning mechanism subsequently classifies as pertaining to the conspiracy. It also captures too many posts that would be “off-topic” or “neutral” science reporting despite mentioning the term “chemtrails.” While Fig. 5 shows some of the same overall trends—e.g., the spike in posts in May 2015—the total numbers do not conform to the difference between all solar geoengineering-focuses posts (Fig. 3) and those without chemtrails (Fig. 4).

Basic “positive” and “negative” sentiments, meanwhile, have shifted significantly. Among all social media mentions including “chemtrails” (Fig. 3), around 33% of tweets displayed a “negative” sentiment during the first 12 months of our analysis spanning mid-2008 to 2009, declining to 18% for the final 12 months from mid-2016 to 2017. That reflects a statistically significant decrease of 1.7% per year (t-statistic = 11.5). During the same time period, overall positive sentiment shows no significant trend, staying near-constant at 9.4% throughout (t-statistic = 0.92). Excluding tweets categorized as propagating the chemtrails conspiracy (Fig. 4), those classified by Crimson Hexagon’s automated sentiment analysis to have positive sentiment decreased slightly from 10.4 to 8.1% over the course of the decade, while those displaying negative sentiment decreased significantly from 30.9% to 13.0% (t-statistics = 3.8 and 9.4, respectively). Note that this only reflects relative sentiment and does not in itself convey greater acceptance of solar geoengineering over the course of the past decade. It does imply that online discourse on solar geoengineering more broadly happens in emotionally more neutral ways, despite the absolute dominance of the chemtrails conspiracy.

Discussion

What can explain the apparent spread of the chemtrails conspiracy? Per the CCES results, chemtrails conspirators are not confined to generally extreme political beliefs. Neither “extreme” Democrats or Republicans are more likely to subscribe to the conspiracy theory than “moderate” ones (Fig. 1). However, further detailed analysis of online behavior reveals an affinity of those tweeting about geoengineering toward other topics that could be grouped into more partisan extremist causes. Table 2 shows the top 25 keywords with the highest ratio between those captured by the overall geoengineering monitor vs. all of Twitter. A sense of a community of conspiracy quickly emerges.

The list features some expected general terms like “climate”, “climate change”, and “sustainability” but otherwise primarily focuses on topics associated with partisan politics. Those include keywords most associated with liberal concern, such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the form of “Monsanto”, and topics typically associated with conservative politics both in the United States and abroad. Some keywords are difficult to categorize, including “Msnbc” and “Fox News”, as we do not know the attitudes displayed toward those terms. Others are more clearly associated with fringe and outright conspiratorial positions. Those include Sen. Ron Paul (Republican, Texas), whose name is often invoked by chemtrails conspirators as offering ‘‘support’’ for their views, right-wing radio personality and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, the term “Talk radio” itself, and terms like “Wikileaks”, “Affordable Care Act”, “Liberty”, “Tea Party”, and “Constitution”. The 26th term not featured in Table 2: “Benghazi”.Footnote 4

Note that Table 2 captures affinities across the entire “geoengineering” monitor, not just “chemtrails” alone.Footnote 5 Despite limitations of the latter, a “chemtrails”-only affinity analysis mirrors that of the broader geoengineering monitor and reveals a similar community of conspiracy (Table 3).

The relative anonymity afforded by Twitter and other online platforms may also play a key role in the spread of conspiracy theories. There are many other differences across social media platforms, though Twitter has indeed become known for having a preponderance of anonymous ‘‘bots’’ (Varol et al., 2017). Even though Crimson Hexagon filters out bots, the general sense remains that Twitter affords its users more anonymity than other platforms, if desired by the user.

Table 4 shows the fraction of a representative sample of ~ 10,000 social media mentions over the full ten-year period by category and platform. Well over half of tweets are categorized as “chemtrails”. Only 21% of (public) Facebook posts and 13% of all other social media posts are in that category. The difference across platforms is highly statistically significant (χ

2 = 2711).Footnote 6 It is clear a much higher fraction of tweets fall into the chemtrails conspiracy camp than do public Facebook posts or those on other online platforms.

The gap between online discourse and popular belief on the one hand and the attention paid to it by scientists on the other is large. An overwhelming majority of scientists dismiss the conspiracy as just that (Shearer et al., 2016). Yet the real-world importance of social media cannot be dismissed. That goes for the Arab Spring (Jamal et al., 2015; Wagner and Gainous, 2013) as well as for US politics (Gainous and Wagner, 2014). The conspiracy similarly has important implications for global governance of solar geoengineering (Cairns, 2016).

Ignoring the chemtrails conspiracy may well have been a viable option at a time when perhaps ~ 5 or even ~ 15% of the general public subscribed to it. Now that the numbers appear to be closer to between ~ 30 and ~ 40% of the US public (Table 1), that may no longer be a viable option. As the 2016 US presidential election has shown, “fake news” can have real impacts (Allcott and Gentzkow, 2017). How then to attempt to address the topic?

While there is a long history of thought on the topic (e.g., Meyer, 2010), the practice of science communication is often more art than science. Climate science communication already raises difficult questions, in part linked to deeper motivations and interests among a host of stakeholders (e.g., Oreskes and Conway, 2010). The very characteristics that make climate change such a difficult public policy problem (e.g., Wagner and Zeckhauser, 2011) complicate addressing the chemtrails conspiracy further. While the US public’s confidence in leaders of the scientific community writ large has been relatively stable since the 1970s (Rainie, 2017), the spread of the chemtrails conspiracy not least reflects a general distrust in science as an institution and in science communicators more broadly (Cairns, 2016; Lewandowsky et al., 2013).

One important question is whether scientific attention to the conspiracy theory helps spread it further. Some chemtrails conspirators take the increased number of articles on the subject itself as evidence that there must be something to their theory. This mirrors what we can observe with those arguing against vaccinating children, often for unwarranted fears of a link between vaccinations and autism (Doja and Roberts, 2006; Miller and Reynolds, 2009). Much like ‘anti-vaxxers’ are hardly persuaded by evidence against their theory, chemtrails conspirators, too, are apparent masters in picking ‘evidence’ to support their views, while ignoring evidence against them. Regardless of possible unintended consequences, fighting tweets with peer-reviewed analyses does not work. Much more promising are attempts to engage at the same level, speaking to chemtrails conspirators directly using social media platforms (e.g. West, 2014).

Conclusion

Chemtrails are not real. Belief in the chemtrails conspiracy is. Between ~ 30 and ~ 40% of the general US public appear to subscribe to versions of the conspiracy theory, numbers only topped by the large fraction (~ 60%) of social media discourse, more on Twitter, focused on the topic. That renders rational conversations around solar geoengineering and its potential role in climate policy even more difficult than it would be absent the chemtrails conspiracy (Burns et al., 2016). It also shows some of the broader implications of this online community of conspiracy with implications well beyond climate policy.

Data availability

Data analyzed using Crimson Hexagon are proprietary and are not publicly available. However, once given access, it is straightforward to duplicate our analysis by following the steps enumerated in the methods section above. All summary data used in this analysis, including CCES survey results, are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

-

We do not cite specific tweets but instead rely on Crimson Hexagon’s algorithm and comprehensive archive of social media posts. In general, and with one notable exception (Thomas, 1999), we do not cite here most online pieces propagating the “chemtrails” conspiracy theory directly. A sampling of them can be found on sites like thesleuthjournal.com. It calls itself an “independent alternative media organization” but mainly serves as one of many hubs for far-reaching conspiracy theories. Similarly instructive is a basic search for YouTube clips mentioning “chemtrails”.

-

The first 10 min of “common content” gathered commonly used political and demographic information.

-

The specific terms change somewhat over time. For example, an affinity table for June 2015–16 includes the terms “Fukushima” and “Al Gore”, whereas an analysis confined to January through June 2017 features “Benghazi” more highly and does not include either “Tea Party” or “Talk Radio”. The overall trends, however, are relatively stable. Keywords featured regardless of which time period is analyzed over the past five years include: “Climate”, “climate change”, “Affordable Care Act”, “Monsanto”, “Fox News”, “Alex Jones”, “Ron Paul”, “British National Party”, and “Liberty”.

-

See our prior discussion of the limitations of a “chemtrails”-only monitor.

-

Simplifying the table to only capture “chemtrails” vs. “not chemtrails” across platforms still results in χ

2 = 1415. Only looking at Twitter versus Facebook results in χ

2 = 197, still indicating a rejection of H

0 hypothesizing equal fractions across platform well beyond the 0.1% significance level.

References

-

Allcott H, Gentzkow M (2017) Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. J Econ Perspect 31(2):211–236. https://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jecper/v31y2017i2p211-36.html

-

Andersen K (2017) Fantasyland: How America went haywire: A 500-year history. Random House, New York

-

Barkun M (2013) A culture of conspiracy: apocalyptic visions in contemporary America. Univ of California Press, Oakland, CA. Google-Books-ID: Rn213R48e2YC

-

Burns ET, Flegal JA, Keith DW, Mahajan A, Tingley D, and Wagner G (2016) What do people think when they think about solar geoengineering? A review of empirical social science literature, and prospects for future research. Earth’s Futur p. 2016EF000461. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016EF000461/abstract

-

Cairns R (2016) Climates of suspicion: ‘chemtrail’ conspiracy narratives and the international politics of geoengineering. Geogr J 182(1):70–84. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/geoj.12116/full

-

Doja A, Roberts W (2006) Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature. Can J Neurol Sci 33(04):341–346. http://journals.cambridge.org/article_S031716710000528X

-

Dunne C (2017) My month with chemtrails conspiracy theorists, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/may/22/california-conspiracy-theorist-farmers-chemtrails

-

EPA U (2000) Aircraft contrails factsheet, Technical Report EPA430-F-00-005. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/00000LVU.PDF?Dockey=00000LVU.PDF

-

Gainous J and Wagner KM (2014) Tweeting to power: The social media revolution in American politics. Oxford University Press, Princeton, NJ. Google-Books-ID: KYdeAQAAQBAJ

-

Gertner, J (2017) Is it O.K. to tinker with the environment to fight climate change?, The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/18/magazine/is-it-ok-to-engineer-the-environment-to-fight-climate-change.html

-

Goertzel T (1994) Belief in conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol 15(4):731–742. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3791630

-

Greenfieldboyce N (2017) Scientists who want to study climate engineering shun Trump. http://www.npr.org/people/4494969/nell-greenfieldboyce

-

Hopkins DJ, King G (2010) A method of automated nonparametric content analysis for social science. Am J Pol Sci 54(1):229–247. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00428.x/abstract

-

House TJ, Near Jr JB, Shields WB, Celentano RJ, and Husband DM (1996) Weather as a force multiplier: Owning the weather in 2025, Technical report, DTIC document. http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecordmetadataPrefix=htmlidentifier=ADA333462

-

Jamal AA, Keohane RO, Romney D, Tingley D (2015) Anti-Americanism and anti-interventionism in Arabic twitter discourses. Perspect Polit 13(1):55–73. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/antiamericanism-and-antiinterventionism-in-arabic-twitter-discourses/B845BE52DC35D6D7FF77A90D6BD7E5FD

-

Keith DW and Wagner G (2017) Fear of solar geoengineering is healthy—but don’t distort our research, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/mar/29/criticism-harvard-solar-geoengineering-research-distorted

-

Lewandowsky S, Gignac GE, Oberauer K (2013) The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PLoS ONE 8(10):e75637, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0075637

-

Lukacs M (2017) Trump presidency ’opens door’ to planet-hacking geoengineer experiments, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/true-north/2017/mar/27/trump-presidency-opens-door-to-planet-hacking-geoengineer-experiments

-

Mahajan A, Tingley D and Wagner G (2017) Fast, cheap, and imperfect? American public opinion about solar geoengineering.

-

Mercer AM, Keith DW, Sharp JD (2011) Public understanding of solar radiation management. Environ Res Lett 6(4):044006, http://stacks.iop.org/1748-9326/6/i=4/a=044006?key=crossref.0f9ca3ba8da0b53b500c2b5793f1d1de

-

Meyer M (2010) The rise of the knowledge broker. Sci Commun 32(1):118–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547009359797

-

Miller L, Reynolds J (2009) Autism and vaccination—the current evidence. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 14(3):166–172. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00194.x/full

-

Neslen A (2017) US scientists launch world’s biggest solar geoengineering study, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/mar/24/us-scientists-launch-worlds-biggest-solar-geoengineering-study

-

Newitz A and Steiner A (2014) Here’s where the chemtrail conspiracy theory actually came from. http://io9.gizmodo.com/is-that-reflective-cloud-about-to-poison-you-and-change-1638680856

-

NRC (2015a) Climate intervention: Carbon dioxide removal and reliable sequestration. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18805

-

NRC (2015b) Climate intervention: Reflecting sunlight to cool earth, Technical report National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18988/climate-intervention-reflecting-sunlight-to-cool-earth

-

Oreskes N, Conway EM (2010) Defeating the merchants of doubt. Nature 465(7299):686–687. https://www.nature.com/articles/465686a

-

Public Policy Polling (2013) Conspiracy theory poll results, Technical report. http://www.publicpolicypolling.com/main/2013/04/conspiracy-theory-poll-results-.html

-

Porter E (2017) To curb global warming, science fiction may become fact, The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/04/business/economy/geoengineering-climate-change.html

-

Pretor-Pinney G and Sanderson B (2006) The cloudspotter’s guide: The science, history, and culture of clouds. Taylor & Francis http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3200/WEWI.59.5.60-61

-

Rainie L (2017) U.S. public trust in science and scientists. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/06/27/u-s-public-trust-in-science-and-scientists/

-

Shearer C, West M, Caldeira K, Davis SJ (2016) Quantifying expert consensus against the existence of a secret, large-scale atmospheric spraying program. Environ Res Lett 11(8):084011, http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/8/084011/meta

-

Streep A (2008) The military’s mystery machine, Popular science. http://www.popsci.com/military-aviation-space/article/2008-06/militarys-mystery-machine

-

Sunstein CR, Vermeule A (2009) Conspiracy theories: causes and cures. J Polit Philos 17(2):202–227. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x/abstract

-

Thomas W (1999) Contrails: poison from the sky. http://www.netowne.com/environmental/contrails/willthomas/contrails.htm

-

Varol O, Ferrara E, Davis CA, Menczer F, and Flammini A (2017) Online human-bot interactions: Detection, estimation, and characterization, arXiv:1703.03107 [cs]. arXiv: 1703.03107. http://arxiv.org/abs/1703.03107

-

Vicario MD, Bessi A, Zollo F, Petroni F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Stanley HE, Quattrociocchi W (2016) The spreading of misinformation online. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(3):554–559. http://www.pnas.org/content/113/3/554

-

Wagner G, Zeckhauser RJ (2011) Climate policy: hard problem, soft thinking. Clim Change 110(3–4):507–521. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-011-0067-z

-

Wagner KM, Gainous J (2013) Digital uprising: The internet revolution in the middle east. J Inf Technol Polit 10(3):261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2013.778802

-

West M (2014) Debunking “Contrails don’t persist” with a study of 70 years of books on clouds. https://www.metabunk.org/debunking-contrails-dont-persist-with-a-study-of-70-years-of-books-on-clouds.t3201/

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the Weatherhead Initiative on Climate Engineering for financial support, Aseem Mahajan for help analyzing the CCES survey, Emma Wheeler for research assistance, and Adam Band, Lizzie Burns, Jane Flegal, David Keith, János Pásztor, Stefan Schäfer, and participants in the 15th Annual Meeting of the Science and Democracy Network as well as the inaugural Gordon Research Conference on Climate Engineering for thoughts and discussion. Thanks to Crimson Hexagon for access to their platform via the Social Research Grant Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T. and G.W. contributed equally to conceptualizing and conducting the analysis and to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests. G.W. co-directs Harvard’s Solar Geoengineering Research Program mentioned in the article. Both DT and GW are on its Advisory Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tingley, D., Wagner, G. Solar geoengineering and the chemtrails conspiracy on social media.

Palgrave Commun 3, 12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0014-3

-

Received: 11 August 2017

-

Accepted: 25 September 2017

-

Published: 31 October 2017

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0014-3

This article has been archived for your research. The original version from Nature.com can be found here.