‘Shpilkin method’: Statistical tool gauges voter fraud in Putin landslide

As many as half of all the votes reported for Vladimir Putin in Russia’s presidential election last week were fraudulent, according to Russian independent media reports using a statistical method devised by analyst Sergey Shpilkin to estimate the extent of voter manipulation.

Advertising

Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed a landslide victory on Sunday that will keep him in power until at least 2030, following a three-day presidential election that Western critics dismissed as neither free nor fair.

The criticism is shared by Russia’s remaining independent media outlets, which have published their estimates of the extent of voter manipulation during the March 15-17 election that saw Putin clinch a fifth term in office with a record 87% of ballots cast.

Massive fraud

“Around 22 million ballots officially in favour of Vladimir Putin were falsified,” said the Russian investigative journalism website Meduza, which interviewed Russian electoral analyst Ivan Shukshin.

Important Stories, another investigative news website, gave a similar number, estimating that 21.9 million false votes were cast for the incumbent president.

The opposition media outlet Novaya Gazeta Europe came up with an even bigger number, claiming that 31.6 million ballots were falsified in Putin’s favour.

That figure “corresponds to almost 50 percent of all the votes cast in the president’s favour, according to the Central Election Commission [Putin received 64.7 million votes]”, said Jeff Hawn, a Russia expert at the London School of Economics.

All three estimates suggest that “fraud on a scale unprecedented in Russian electoral history” was committed, added Matthew Wyman, a specialist in Russian politics at Keele University in the UK.

The three news outlets all used the same algorithmic method to estimate the extent of voter fraud. It is named after Russian statistician Sergey Shpilkin, who developed it a decade ago.

Shpilkin’s work analysing Russian elections has won him several prestigious independent awards in Russia, including the PolitProsvet prize for electoral research awarded in 2012 by the Liberal Mission Foundation.

However, he has also made some powerful enemies by denouncing electoral fraud. In February 2023, Shpilkin was added to Russia’s list of “foreign agents”.

Shady turnout figures

The Shpilkin method “offers a simple way of quantitatively assessing electoral fraud in Russia, whereas most other approaches focus on detecting whether or not fraud has been committed”, said Dmitry Kogan, an Estonia-based statistician who has worked with Shpilkin and others to develop tools for analysing election results.

This approach – used by Meduza, Important Stories and Novaya Gazeta – is based “on the turnout at each polling station”, said Kogan.

The aim is to identify polling stations where turnout does not appear to be abnormally high, and then use them as benchmarks to get an idea of the actual vote distribution between the various candidates.

In theory, the share of votes in favour of each candidate does not change – or does so only marginally –according to turnout rate.

In other words, the Shpilkin method has been able to determine that in Russia, candidate A always has an average X percent of the vote and candidate B around Y percent, whether there are 100, 200 or more voters in an “honest” polling station.

In polling stations with high voter turnout, “we realised that this proportional change in vote distribution completely disappears, and that Vladimir Putin is the main beneficiary of the additional votes cast”, said Alexander Shen, a mathematician and statistician at the French National Centre for Scientific Research’s Laboratory of Computer Science, Robotics and Microelectronics in Montpellier. .

To quantify the fraud, Putin’s score is compared with what the result would have been if the distribution of votes had been the same as at an “honest” polling station. The resulting discrepancy with his official score gives an idea of the extent to which the results were manipulated in his favour.

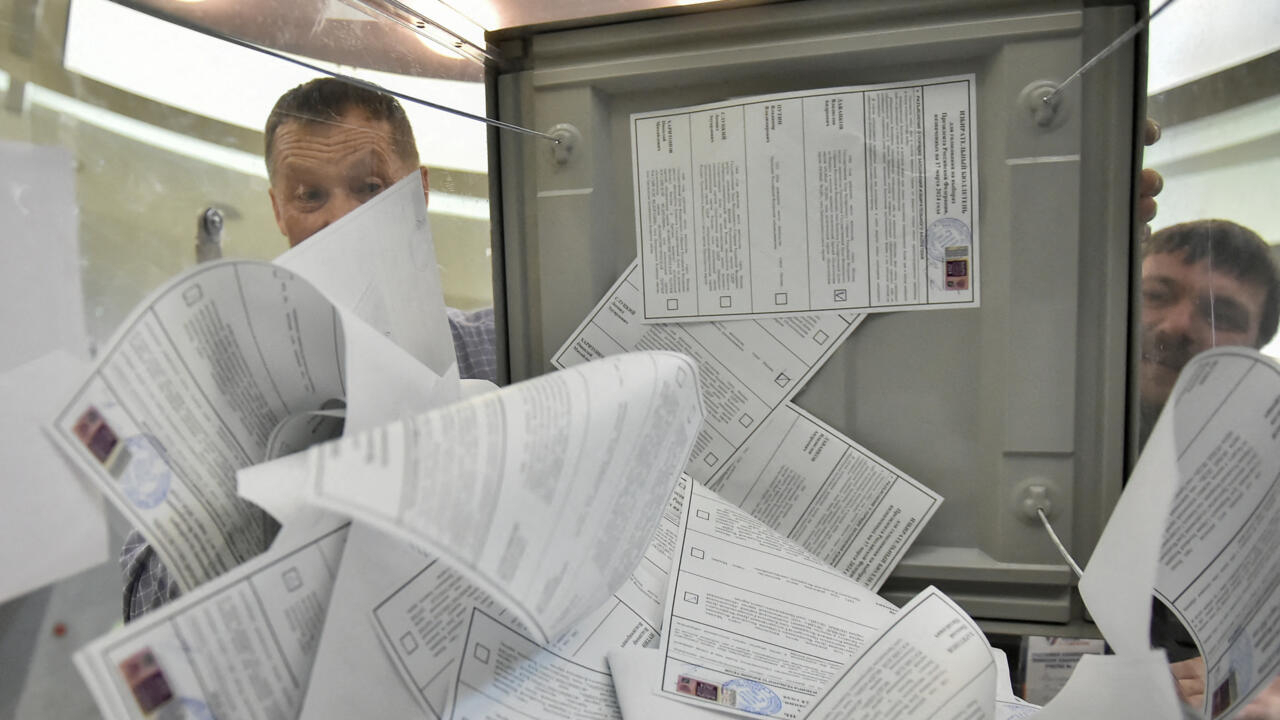

The Shpilkin method makes it possible to put a figure on the “ballot box stuffing and accounting tricks to add votes for Vladimir Putin”, said Shen.

Limitations of the Shpilkin method

However, “this procedure would be useless if the authorities used more subtle methods to rig the results”, Kogan cautioned.

For instance, if the “fraudsters” took votes away from one of the candidates and attributed them to Putin, the Shpilkin method would no longer work, he explained.

“The fact that the authorities seem to be continuously using the most basic methods shows that it doesn’t bother them that people are aware of the manipulation,” Kogan added.

Another problem with the Shpilkin method is that it requires “at least a few polling stations where you can be reasonably sure that no fraud has occurred”, said Kogan, for whom that condition was not easy to be sure about in last week’s presidential election.

“I’m not sure we can really reconstruct a realistic distribution of votes between the candidates, because I don’t know if there is enough usable data,” added Shen.

Does this negate the validity of the estimates put forward by independent Russian media?

Kogan said he stopped trying to quantify electoral fraud in Russia in 2021. He explained: “At the time, I estimated that nearly 20 million votes in the Duma [lower house] election had been falsified. Then I said to myself, ‘what’s the point in going to all this trouble if the ballots were completely rigged?’”

Nevertheless, he said it is important to have estimates based on the Shpilkin method because even if it is difficult to get a precise idea, “the order of magnitude is probably right”.

These rough estimates are also “an important political weapon”, said Wyman, stressing the need to “undermine the narrative of the Russian authorities, who claim that the high turnout and the vote in favour of Putin demonstrate that the country is united”.

It is also an important message to the international community, added Hawn.

“The stereotype is that Russians naturally vote for authoritarian figures,” he said. “By showing how inflated the figures are, this is a way of proving that the reality is far more nuanced.”

This article has been translated from the original in French.