How Europe’s Conspiracy Influencers Went From Covid-19 to the Climate

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

On a cold morning in late February, farmer Gareth Wyn Jones was standing with a few dozen other protesters outside the annual conference for the Conservative Party in Wales. Inside the venue, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was giving a speech to the Welsh branch of the Conservatives. Wyn Jones and other farmers were here to voice anger at policies by the Labour Party and to demand Sunak’s support. With their tractors parked in a row behind them, many of the protesters held up signs that read “No Farmers No Food”.

According to Wyn Jones, Conservative Member of Parliament Virginia Crosbie approached and asked, “Would you like to meet Rishi?” Wyn Jones happily agreed. Along came Sunak in his signature slim-fit suit, looking even more like a finance bro than usual next to Wyn Jones, wearing his flat-cap and thick beige jacket. The Prime Minister gave a short speech to the assembled crowd criticizing Labour’s agricultural policies and then listened to Wyn Jones’ concerns.

Wyn Jones complained about environmental policies including a proposal that 10 percent of farmland must be given over to trees and 10 percent given over to quality wildlife habitat, and also lamented a ban on badger culling.

Perhaps keen to avoid the kind of mass farmer protests underway elsewhere in Europe, Sunak had recently been making overtures to the UK’s farming industry. This year, farmers blockaded Brussels, Berlin, and Paris, among other cities, with a set of broad demands around their struggling business model, as well as to protest environmental requirements introduced as part of the EU’s push towards a green transition.

After their conversation, Sunak posed for photos with a ruddy, grinning Wyn Jones.

But in posing for photos, Sunak had endorsed a group that pushes conspiracy theories. The “No Farmers No Food” campaign that Wyn Jones is part of has shared false information about climate action and is vehemently anti-net zero. An online organizing document claimed that “Unelected globalists” were “killing farmers” and would force the population to “eat bugs.” No Farmers No Food was founded by a PR consultant called James Melville. Scottish, with salt-and-pepper hair and clever eyes, Melville is a frequent commentator on the Fox News-style TV channel GBNews, and has shared fake news that governments are planning to force people into “climate lockdowns.”

Prime Minister Sunak’s appearance with No Farmers No Food follows a U-turn last year on key climate commitments. Ahead of a general election this Thursday, July 4 that could see the Conservatives defeated after 14 years in power, Sunak has also led endless attacks on the Labour Party’s moderate green policies.

Wyn Jones believes none of the UK party election manifestos address agriculture meaningfully — and he resents parties “blaming” farmers for climate change. “We are sleepwalking into food shortages, a lot quicker than people understand,” he says. When asked about conspiratorial posts shared by No Farmers No Food and its founder James Melville, Wyn Jones laughs deeply: “There’s always a conspiracy theory behind everything,” and adds, “I’ve been called a right-wing extremist for my opinions, and there’s no person more middle of the road than me on God’s earth — I hate politics.”

Wyn Jones previously appeared on countryside-related TV shows on the BBC, before falling “out of favor with the mainstream media.” Since then he’s built an impressive online platform — claiming to be the world’s most-followed farmer. Apart from 340,000 followers on Facebook, Wyn Jones has a staggering 2.2 million subscribers to his YouTube channel. When asked how it grew so rapidly from only 3,000 subscribers in May last year, Wyn Jones puts it down to, “Honesty, and a bit of luck,” while later noting that he has “people that help me with that kind of stuff.” Despite the huge subscriber base, most of Wyn Jones’ YouTube videos have only a few thousand views, with some scoring fewer than a thousand.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak speaking with farmers after he delivered a speech at the Welsh Conservatives Conference in February. (Photo by Peter Byrne/PA Images via Getty Images)

PA Images via Getty Images

No Farmers No Food founder James Melville also has a large online platform, with nearly half a million followers on X, formerly Twitter — double that of the far more renowned right-wing British commentator Toby Young — many of whom have long alphanumeric strings as handles, no profile picture, and have only tweeted a couple of times, all typical features of bot accounts. No Farmers No Food’s X account also appears to have many bot followers, which might explain how it hit 60,000 followers so soon after launching in January (it currently has 72,000 followers), with 30,000 in just the first five days.

Melville wasn’t always so focused on climate action and farmers. During the pandemic, he got involved with Covid-skeptic anti-lockdown groups, including Together Declaration, which according to data analysis by Rolling Stone and UK social media research company Prose Intelligence, started posting more about the climate from mid-2022 as public interest in vaccines and lockdowns waned. More recently, Together Declaration launched a “No To Net Zero” campaign.

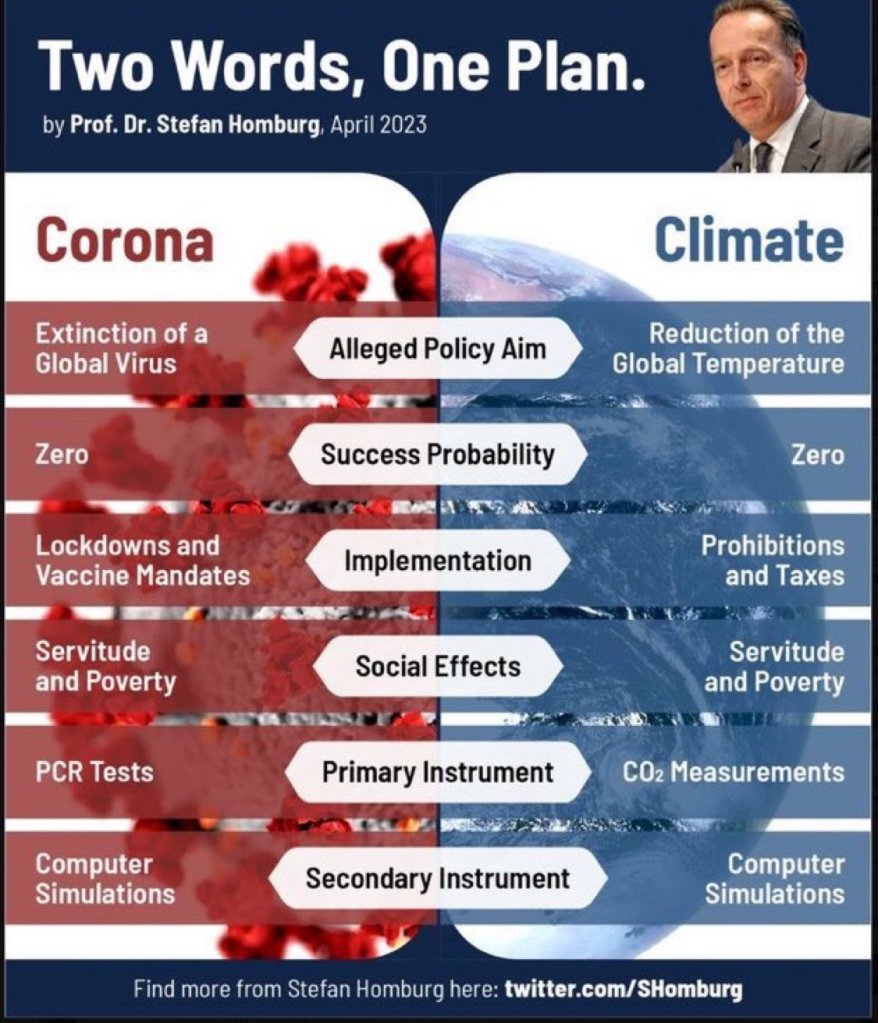

Many of the group’s posts link efforts to reduce emissions to a conspiracy theory about “15-minute cities,” a fairly innocuous urban planning concept to make amenities easily accessible to city residents, but which has been warped into allegations that the idea is just a pretext for imposing a totalitarian system limiting citizens’ right to movement. Other posts claim policies to reduce emissions from vehicles are part of a “war on cars,” or that health risks from poor air quality are a hoax. This pivot towards climate posts mirrors Melville’s own. Since mid-2022, Melville started tweeting more about the climate and net zero policies, claiming that there would be “climate lockdown trials” for people leaving 15-minute zones, and suggesting both Covid-19 and climate change were manufactured crises designed to impoverish citizens and impose high taxes. At a recent Together Declaration event, Melville called for a fight back against “Poundland authoritarians” enacting net zero policies.

Increasingly, conspiratorial influencers who built large audiences during the Covid-19 pandemic have turned to false and misleading claims about the climate and other topics to keep their audiences engaged. They are in turn influencing political parties and shaping discussion on climate policy. When the farmers’ protests broke out, these influencers sought to co-opt them into the “climate culture wars,” framing the complex demands of farmers into a reductive anti-net zero narrative. The strategy appears to be working. By the time the European parliamentary elections had rolled round in early June this year, the EU had already rolled back on key green pledges — in the wake of tractor blockades and sometimes violent protests roiling major cities. The elections themselves saw record gains for far-right parties, while green parties lost ground amid disputes over the costs of the green transition, both real and imagined.

While Europeans remain overwhelmingly in favor of climate action, the U.S. style of partisan disputes and paranoid theories has punctured the previous broad consensus on tackling climate change, diverting the conversation into bizarre claims of secret government plots against its citizens — such as wanting to make everyone eat bugs. “Climate is now firmly embedded in the culture wars,” says Jennie King, director of climate disinformation research and policy at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue. As climate has become a more salient topic, influencers began to experiment with climate themes, she says. “They saw that it was successful and doubled down on that strategy,” adds King, whose research shows that as Covid-19 receded, a vacuum formed in spaces online. “Bad actors flooded into those spaces and weaponized them in pursuit of other agendas, one of which was opposition to the climate movement.”

One consequence of this shift is that conspiratorial narratives about climate action have entered the mainstream, filtered through far-right voices into the speeches of more traditional conservative parties. And this is now happening all over Europe.

“Climate is now firmly embedded in the culture wars”

A calm middle-aged man with a plain black T-shirt, clean-shaven face, and dark, inexpressive eyes looks into the camera, speaking German. “Whoever thinks that IKEA is just a furniture store only sees half of the truth,” he says, referring to the Swedish multinational furniture chain IKEA. “Because it’s also a place of re-education.” IKEA, he says, has vowed to make 50 percent of its in-store restaurant menu vegan by 2025 in Sweden to limit its carbon footprint. Allegedly, the man adds, the store will soon cease to offer its signature meatballs, and by 2030, the entire menu will become carbon-neutral. “IKEA wants to make us vegans!” he concludes, waving his right fist theatrically.

The man is Boris Reitschuster, one of Germany’s prominent “alternative journalists.” In his video, titled “How IKEA wants to make us vegan: The fight against hot dogs and meatballs” and published on YouTube in March 2024, Reitschuster rants to his 371,000 subscribers about the umpteenth “disgusting” move made in the name of climate action. “It’s not up to a furniture store to explain what people have to eat,” he says. In another video, he compares Germany’s supposed green future to North Korea and the stone age.

Reitschuster is one of the most prominent figures in Germany’s “alternative media” scene, and this is not the only time he has posted against climate-related issues. From his online platforms — which, apart from YouTube, include 253,800 X followers, and nearly 240,000 subscribers to his channel on Telegram, an immensely popular platform for Germany’s conspiratorial and far-right scenes, as well as his popular website, reitschuster.de — he frequently authors or amplifies contrarian takes against so-called climate ideology.

“Are the climate police now coming?” reads the headline of one of his articles published in December 2023. Another article posted to his Telegram channel in February 2024, and seen by nearly 110,000 people on the platform alone, warned against the supposed onset of state surveillance and threat of violence to enforce recycling quotas in Germany. More recently, he called out a weather announcer on Germany’s public broadcaster ZDF for “exploiting floods for climate ideology,” and warned that renewable energies were increasing the risks of blackouts on the European grid.

Some influencers who built large audiences during the Covid-19 pandemic have turned to false and misleading claims about the climate

Reitschuster’s online success largely goes back to the Covid-19 pandemic, when his profile shot up quickly. Since Covid, Reitschuster has posted consistently about climate-related issues — one of his most viewed and engaging recent posts on Telegram lambasted a “green” journalist for her “dream of a revolution and eco-dictatorship.”

Like other conspiratorial influencers in Germany, Reitschuster used to be a respected journalist for traditional media. After 16 years as an award-winning Russia correspondent at German newsweekly Focus, Reitschuster left in 2015, citing “different opinions.” He freelanced for a few years for international media including The Guardian and The Washington Post, as well as some of Germany’s niche far-right magazines. In 2019, he began regularly posting on his website reitschuster.de. But it was the pandemic that catapulted him into the premier league of Germany’s conspiratorial world. He railed frequently and passionately against vaccines and Covid restrictions, and in April 2020, when Facebook began deplatforming accounts sharing false information about Covid-19, he opened his Telegram channel. As he warned against “deadly” Covid-19 vaccines and called out Germany’s restrictions, his following skyrocketed, peaking at some 319,000 followers in early 2022.

Reitschuster claims his website garners more than 50 million hits per month, apparently supported by donations and an affiliated shop selling anything from mugs to Covid-19 face masks to T-shirts sporting sayings such as “stop war,” and “only dead fish swim with the current.” Newsguard noted that it did not fulfill “basic requirements for credibility and transparency.” He was also awarded a sarcastic “golden tinfoil prize” by a nonprofit organization for education about conspiracy ideologies, sects, ideological abuse, and extremism for allegedly giving conspiracy theories and misinformation a “seemingly serious look.”

As Covid-19’s prominence in the news cycle was overshadowed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Reitschuster’s following plateaued, then tumbled. Being critical of Vladimir Putin and his war proved unpopular among Germany’s Covid-skeptics and conspiratorial community. Tens of thousands of people left his Telegram channel in the wake of the invasion.

Since then, he changed tacks. “Reitschuster has written far fewer posts about Putin and Russia — he keeps a very low profile on this topic,” says Josef Holnburger, a political data scientist who researches conspiracy ideologies and right-wing extremism at the nonprofit Center for Monitoring, Analysis, and Strategy (CeMAS). In recent months, Reitschuster’s audience appears to have warmed to his environment content, which data analysis showed has taken up as much as 30 percent of his coverage on certain weeks. (The rest of his coverage is exactly what you’d expect from a “culture warrior”: Covid-19 restrictions — yes, still — migration, LGBT+ rights, and attempts to unmask the supposed hypocrisy of “globalists.”)

But it was the farmers’ protests, which exploded in Germany in January 2024, bringing central Berlin and other cities to a standstill with tractors and demonstrations, that really breathed new life into Reitschuster’s audience. As protests spread rapidly across Europe, reischuster.de’s following began growing again for the first time in nearly two years.

Reitschuster’s turnaround is far from an isolated one. “The farmers’ protests provided a strong boost to this scene,” Holnburger says. “Several channels attempted to hijack the positive image of farmers and frame the demonstration as an uprising of the middle classes and consumers.”

One of the most popular conspiratorial channels on German-speaking Telegram is AUF1, a self-styled far-right news organization that grew popular during the pandemic. On its website, you can buy a t-shirt emblazoned with “I love CO2” for about $30. Other shirts have slogans like “Germany for the Germans” and “White Lives Matter.” It’s an indication of what at least partly motivates some of these platforms: the chance to make a buck off xenophobia and hate.

AUF1’s founder, Stefan Magnet, has quite the resume, starting with a leading role in Austrian right-wing extremist youth organization “Bund free Youth” (BfJ), a photograph with convicted Holocaust denier Gottfried Küssel in 2006, and an arrest in 2007 on suspicion of having violated a law banning Nazi parties. (He was released after six months of pre-trial detention and acquitted in May 2008.) He also traveled to Russia with a delegation of Austria’s far-right FPÖ party in 2016 to sign a working agreement with Putin’s United Russia party.

Magnet has said that Covid-19 restrictions mobilized him to launch AUF1 in 2021. Since then, AUF1 has expanded from its Austrian base — frequently interviewing politicians from Germany’s far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, currently ranked second in national opinion polls. AUF1’s Telegram channel has also grown to become the biggest channel of its kind in Germany, with 274,000 followers at the time of writing. During 2023, subscribers seemed to have plateaued, even at one point falling, but the channel has added 16,000 followers since the start of 2024, tracking with the boost other conspiracy influencers received since the farmers’ protests.

Like Reitschuster’s followers, AUF1’s audience appears to have warmed to climate-skeptic content. One of its most successful posts in recent months, which misleads readers into thinking that NASA has found the planet to be cooling, was viewed by some 365,000 people. Another popular post questions whether “breathing to blame for climate change,” while citing a study that supposedly declares babies “climate killers.”

In response to questions from Rolling Stone, AUF1’s founder Stefan Magnet railed against “climate hysteria,” saying it was unscientific: “Our fundamental position at AUF1 is that science is always in flux and that all sides must be heard.” He blamed corporations both for damaging the environment and creating hysteria about climate change, so that the population can be “controlled and oppressed.”

While AUF1 has promoted conspiracy theories in Germany that appear to have filtered through to the far-right AfD party, one of Spain’s most notorious spreaders of disinformation has gone one step further — recently pulling off a shocking triumph in European elections.

Luis ‘Alvise’ Perez Fernandez, leader of the group Se Acabo la Fiesta, on July 1 (Photo By Eduardo Parra/Europa Press via Getty Images)

Europa Press via Getty Images

On June 8, 2024, beneath the strobe lights of a Madrid nightclub, a bearded 30-something grinned with child-like glee as all around him men toasted him, some brandishing signs reading, “Se Acabó la Fiesta,”, or, “The Party is Over.” This was the name of a conspiracy-driven campaign, and Luis “Alvise” Perez had just won three seats in the EU’s parliament. Against all odds, his platform was the sixth most voted force with almost 5 percent of the vote.

Alvise became notorious during the pandemic for anti-vax and anti-lockdown content on his online platforms, spreading false statements about vaccines, masks, and Spain’s relatively strict lockdown policies. Since then, he has broadened his message to all elements of the culture wars, including posts about the climate and farmers’ protests, though he is best known for his bombastic, Trumpian promises to lock up opponents and deport immigrants.

While many influencers built careers spreading misinformation around the pandemic, Alvise is a rare example of someone who has pivoted from online hoaxes into running å— and winning — in an election.

“Alvise can be classified as a ‘disinformation entrepreneur,’” says Ana Romero, a researcher at EU Disinfo Lab. Much of his activity has been aimed at “discrediting traditional politicians, attacking the government, and gaining personal influence,” says Romero.

Even by the standards of the far-right, Alvise stands out for his reliance on lies about his opponents. He has been ordered to pay damages for spreading a hoax about the former mayor of Madrid and posting private photos of a journalist. He also faces several additional ongoing accusations of defamation against other public figures. Even so, his message seems to have resonated with voters exhausted by years of successive corruption scandals and hungry for an outside voice. Alvise rails against the political “caste,” borrowing a populist trope first coined by the anti-austerity left-wing Podemos party in the early 2010s, before being wielded by Argentina’s new far-right firebrand president Javier Milei against anyone who disagreed with him. Alvise’s claims tap into widely held feelings — even if they make little or no sense. In a recent post, Alvise suggested that dengue infections were caused by immigration, and that “international interests” had coordinated to release the mosquitos that carry the virus.

At the final event of his European election campaign, Alvise appeared wearing a T-shirt with a QR code leading to his Telegram channel, which has a much greater reach than any other political force, but doesn’t tell the whole story behind his rise.

“He is not a product of Telegram, he is a product of his clients,” says Marcelino Madrigal, an expert in the far right and online misinformation networks. “He claims to live off his millions of followers. In reality, he lives off the money and resources provided by a minority of them.”

Alvise has previously worked for a far-right anti-abortion, anti-LGBT campaign group with links to the U.S.-based Howard Center for Family. In response to questions about his funding, Alvise told Rolling Stone that his campaign was entirely supported by “donations from readers.” He refused to provide any further details of campaign financing. “There is an attempt to cast doubt on someone financed by his own community, because of big media’s inability to believe what we have done.”

Alvise has proven adept at portraying a range of issues as part of a plot by a shadowy elite against the average voter. Following the outbreak of farmers’ protests in Europe, he at one point dedicated almost half of his posts to the issue, often blaming competition from Moroccan farmers or implying a plot organized by the center-left government. This coincided with a boost in subscribers since January.

The jump from anti-immigrant fearmongering to hoaxes around climate change is also happening in France.

During the farmers protests, one prominent conspiracy theory channel usually exclusively dedicated to anti-immigration content expanded their coverage to issues around climate, portraying efforts to reduce emissions as another tool by elites to supposedly attack the white European population, alongside the racist conspiracy theory known as the “great replacement.” This rhetoric is increasingly reaching the far-right National Rally (RN) party, which is expected to win in second-round voting in parliamentary elections on Sunday July 7. Some RN candidates have pushed theories including that that the moon landings were faked and that Covid vaccines made people magnetized, while several also attacked the science of climate change.

A similar trend is playing out in the UK ahead of its own general election on July 4. During the campaign, former Conservative energy minister Chris Skidmore blamed Prime Minister Rishi Sunak for breaking the consensus on climate action and stoking polarization — even saying he would vote Labour in the upcoming election as a result. Last year, the Conservatives’ own transport secretary warned against “15-minute cities” and claimed CCTV would control how often people could go shopping.

“As the climate has become a more polarized topic, and has really been taken up by right-wing parties and the more extreme factions of centrist parties, it has weakened the public mandate,” says Jennie King, the climate disinformation researcher.

She cautions against drawing a direct line between conspiracy influencers’ output, election results and government policy, but argues that it has made the topic more divisive, with a growing risk that climate action becomes perceived as just another so-called “woke” concern. She adds that extreme online views are spilling over into the real world, with people invading council meetings, issuing death threats, and accusing politicians of being shills for an insidious form of green tyranny that wants to enslave them.

“All of this,” King warns, “creates the worst possible enabling environment for the kinds of really ambitious and quite seismic systemic forms of climate action that the science says we need to be pursuing.”