Will We See the Deep State Playbook Again in 2024?

As of a few weeks ago, when the New York Times, 91 percent of whose core readers are Democrats, ran an op-ed video titled “It turns out the ‘deep state’ is actually kind of awesome,” both sides of our political divide acknowledged the deep state’s existence. But they differ sharply about what it actually is. For Republicans, it’s arbitrary bureaucrats enacting policies that limit people’s freedom. For Democrats, it’s the real-life model for the series Parks and Recreation or Space Force, where decent administrators use the government to serve Americans.

This second model might be more convincing were it not for the fact that, at its upper echelons, the deep state has created a group of Washington-based operators very different from the Parks and Recreation cohort: powerful people working behind-the-scenes to affect policy through connections to debt-funded defense and domestic administrative agencies and their corporate, university, nonprofit, and media outgrowths. These operators’ moves are subtle and hard to trace, predicated not on overt “power plays” but on more modern techniques for control: the manipulation of language and the dissemination of narratives.

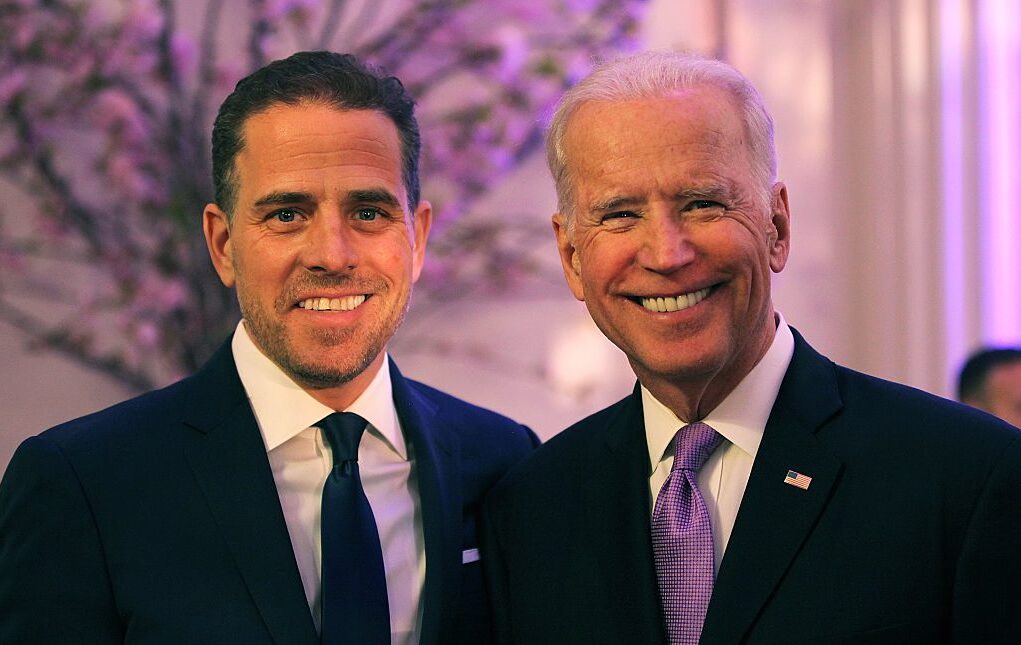

The last time these operators tipped their hand to the public was October 2020, after the New York Post released a report about Hunter Biden’s business activities: an “October Surprise” that could have cost Joe Biden the presidency. The operators’ response to this report has been memorialized by critics with the shorthand “spies who lie,” and there is widespread agreement that it diminished President Trump’s re-election chances. Yet the strategies behind it have yet to be fully examined and linked to a 50-year run of tactics, which, this election year, these operators might use again.

The chronology of the “October Surprise,” and the ensuing response, is extensively chronicled and deceptively straightforward.

On October 14, 2020, twenty days before the election, the New York Post released a report “reveal[ing] that it had obtained emails from Hunter Biden’s laptop, which a Delaware repair-shop owner said he had abandoned.” These emails contained suggestive facts about Biden Jr.’s possible influence-peddling in Ukraine and (as revealed in an October 15 follow-up story) in China, and included connections to his father.

Five days later, on October 19, 51 former intelligence officials signed a public letter released via POLITICO’s Natasha Bertrand, who disclosed that the letter had been provided to her by Nick Shapiro, a former aide to one of its signers, John Brennan—George W. Bush’s deputy CIA director, Barack Obama’s CIA Director, and a vocal opponent of President Trump. The headline of Bertrand’s story describing the letter read “Hunter Biden story is Russian disinfo, dozens of former intel officials say.” Though Bertrand acknowledged that “there has been no immediate indication of Russian involvement in the release of emails the Post obtained,” she also wrote that “its general thrust mirrors a narrative that U.S. intelligence agencies have described as part of an active Russian disinformation effort aimed at denigrating Biden’s candidacy.”

On October 19 and 20, both the signers and the story circulated. One signer, Jeremy Bash, a former CIA and Department of Defense chief of staff during President Obama’s administration, appeared on MSNBC, arguing that “this looks like Russian intelligence. This walks like Russian intelligence. This talks like Russian intelligence.” CNN analyst John Avlon claimed that the letter “parallels something I heard in an interview with a former national counterterrorism expert, saying it has all the hallmarks of a Russian disinformation campaign.”

On October 22, the letter provided Vice President Biden ammunition in the second and final presidential debate, which was watched by 63 million people, and which viewers (by a 14 percent margin) thought Biden won. “Look,” Biden said, when the subject of the laptop was raised, “there are 50 former national intelligence folks who said that [the laptop] is a Russian plan… a bunch of garbage. Nobody believes it except [Trump]….”

This was a blatant misrepresentation of the letter that went uncorrected by any of its signers. The letter did not call the laptop’s content “disinformation,” which in the intelligence community is understood to mean “false or intentionally misleading information that aims to achieve an economic or political goal.” Instead the letter posited an “information operation,” which, among intelligence professionals, means “the collection of tactical information about an adversary as well as the dissemination of propaganda in pursuit of a competitive advantage over an opponent.” This information can be true or false.

In other words, what the letter actually said was that the Hunter Biden information could be true, and that it could be part of a Russian operation to help elect Trump president—a very different message than reporters or signers emphasized at the time, and a message that was not cogently stated in the letter.

What the letter also should have said, in the interest of transparency, was that some of its signers thought that the laptop’s information was true. Indeed, several later went on record stating that they believed this to be the case, and that they believed or assumed their fellow signers thought so as well. One, Douglas Wise, said that “all of us figured that a significant portion of that content had to be real to make any Russian disinformation credible,” and three other signers told the Washington Post that they agreed with this view. (Emphasis added.) Thomas Fingar, a signer who had served as the top intelligence official at the State Department, said that “pure fiction is less likely to fool target audiences. I suspect but do not know that other signers have drawn the same lessons.” Another signer told the Post that “‘a Russia information operation’…would make sense only if a significant amount of the material was true.” This meant that, in the eyes of some signers, it was likely that the Democratic nominee for President had indirect ties to the Ukrainian and Chinese governments.

Making these and other comments two years later, when the content of the laptop had been verified by multiple news outlets and House Republicans had called them in for interviews, some of the letter signers also cited the “information operation” language as proof of their sincerity, and blamed journalists for the confusion. “There was message distortion,” James Clapper, Under-Secretary of Defense under Bush, and Director of National Intelligence under Obama, said—even as he repeated the distorted message. “All we were doing was raising a yellow flag that this could be Russian disinformation…”

Thomas Fingar was more withering: “No one who has spent time in Washington should be surprised that journalists…misconstrue oral or written statements…the statement…was carefully written to minimize the likelihood that what was said would be misconstrued…”

This explanation provided helpful cover, but was disingenuous. Why would people so versed in Washington misinterpretations fail in their letter to define a key term, “information operation,” and then fail to correct reporters’ misinterpretations, if the meaning of the letter was really intended to be clear?

Evidence that the letter was probably not intended to be clear surfaced when the investigating House Committees released excerpts of their questioning of some of the letter’s signers. According to the testimony, the main mover behind the letter, its co-drafter and seemingly its organizer, was Michael Morell, the Deputy and Acting Director of the CIA under Obama. Morell’s impetus for the letter was a conversation with Antony Blinken, a Biden campaign aide who had also served from 2009 to 2013 as Vice President Biden’s National Security Adviser and had longstanding ties to Hunter Biden.

According to CNN, “Morell testified before the committees that he had a phone call with Blinken about the Hunter Biden laptop story in the New York Post, and they discussed possible Russian involvement in the spreading of information related to Hunter Biden.” According to the New York Post, “Blinken’s October 2020 outreach…was credited by Morell with inspiring the letter, though Morell says Blinken…didn’t specifically ask him to write it.”

Morell testified that his goals in initiating the letter were to “share [the] concern with the American people that the Russians were playing on this issue; and…to help Vice President Biden…because I wanted him to win the election.” In an email between Morell and Brennan, later obtained by Just the News, Morrell noted that he was “trying to give the campaign, particularly during the debate on Thursday, a talking point to push back on Trump on this issue.”

As much of this information became public, the implicated players and their allies, again, responded by parsing language. According to Blinken, “With regard to that letter, I didn’t—wasn’t my idea. didn’t ask for it, didn’t solicit it. And I think the testimony that…Mike Morell, put forward confirms that.” House Democrats took the same line.

So did establishment journalists in Washington. Aaron Blake at the Washington Post cited his colleague Glenn Kessler, whose February 2023 column on the letter had been the first to distinguish between “information operation” and “disinformation,” to argue that “the [letter’s] statement was more nuanced than it was initially described…” Blake ended his piece with a quote from Mark Zaid, the lawyer representing a number of letter signers, that “What [the] GOP is doing is far greater politicization than what they allege of Dems”—shifting the story back to a safely partisan arena.

What these parsings and hedgings and re-directions suggest would be par for the course in an episode of Law and Order: the effort to obscure coordinated wrongdoing by people who committed the wrong in the first place in order to keep unwarranted gains. In the case of the letter, its signatories lived at the heart of the “swamp” that Trump was increasingly targeting. Of the 19 signers listed first (by prominence rather than alphabetically), 14 had links to defense contractors or to security firms which leverage their principals’ defense and intelligence connections in Washington. Seven of these 19 had links to the international schools and think tanks which help feed personnel to defense and intelligence agencies, and seven of these 19 appeared regularly on networks staffed by journalists who report on defense and intelligence policy from insider leaks.

In some cases, the interconnections between these players are glaring. One of these is Morell, who in March 2020 was described as a contributing columnist for the Washington Post and on Nov. 12, 2020 was reported to be one of President-elect Biden’s top two contenders for CIA director before progressives stalled his nomination. Another is Brennan, whose aide leaked the letter to POLITICO, and who in 2022 became a principal at WestExec Advisors, the contracting firm founded in 2017 by Blinken. A third is Avlon, who spoke on October 20, 2020, with such certainty of Russian “disinformation” and is now running as a “centrist” Democrat in New York’s first Congressional district, working “to build the broadest possible coalition to defeat Donald Trump, defend our democracy, and win back Congress from his MAGA minions.”

Sometimes they’re quieter, as with signer Michael Vickers: a career CIA-and-Defense official famous enough inside Washington to have been written into a movie by Aaron Sorkin, the court poet of the governing elite. Vickers now serves on the board of the American subsidiary of the world’s seventh largest defense contractor. Often, these quieter connections span education and social life. Jeremy Bash, the signer who on October 19 appeared on MSNBC arguing that the laptop “looks,” “walks,” and “talks like Russian intelligence,” comes from a prominent, Washington-centric background and was educated at elite universities; he was married to and remains “very good friends” with Dana Bash, who comes from a prominent, Acela-corridor background and is CNN’s chief political correspondent. Michael Vickers is the ex-husband of the CEO of the fifth largest defense contractor in the United States.

Washington institutions are the long-time lubricators of these links, and not just the CIA and the Defense Department. Booz Allen Hamilton, a major player linked to covert CIA missions since the 1950s, is on the resume of one prominent signer. The School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins, a seed-ground of Cold War strategy and later of the Iraq War, is on the resume of two others, including Michael Vickers. The New York Times’ Washington bureau and the Washington Post, helmed by a revolving door of insiders, have shaped coverage in directions helpful to these movers since the 1950s; POLITICO, for its part, is a de-facto spin-off of the Washington Post. The Atlantic, a magazine of the establishment elite which has run several pieces papering over, equivocating about, or strategically re-directing questions regarding press coverage of the October 2020 letter, is run by the grandson and biographer of the founder of SAIS.

Decade by decade, these movers and those like them have shown themselves willing to enact October 2020–style plays to protect or expand their power bases. Their methods are always the same: language manipulation and narrative distortion, followed by dissemination via pliant journalists of the distortions, followed by parsing of the language to escape blame.

The examples proliferate, and they’re discouraging reading for those committed to representative government, reportorial diligence, or even effective policymaking.

In the 1970s, Richard Nixon, trying to bring intelligence agencies under direct White House control after a quarter-century of foreign misadventures from Iran and Guatemala to Cuba and Vietnam, was deposed off leaks to the Washington Post from anonymous sources inside these agencies. But the story that got told by the press was about intrepid reporters defying Washington power centers and bringing down a president. Wondering how on earth this distortion might have happened, Renata Adler, the New Yorker reporter who had worked with the House Committee investigating Richard Nixon, wrote that reporters relying on intelligence sources had corrupted their own material. They had obscured obvious points thanks to the fact that “a whole lexicon of euphemisms, metaphors, and misnomers has slipped into investigative reporting from… in just such a euphemism…the ‘intelligence’ agencies of government” that “actually blur what the subject of investigation is.” What Adler saw then is just what “disinformation” and “information operation” represent today.

But what Adler observed repeated itself long before today, as early as the late 1980s, when elements of the Reagan administration, linked to burgeoning think tanks and supported by a congressional minority led by Congressman Dick Cheney, colluded to unconstitutionally fund the Nicaraguan contras against congressional legislation prohibiting it. Structurally, this was a story about what Theodore Draper, in his book on the subject, described as the “usurpation of power by a small, strategically placed group within the government.” But this wasn’t the story that ended up being emphasized by a press corps which had “become more preoccupied with daily coverage” than with “probing, investigative reporting.” Instead the story was about Ronald Reagan’s hard-charging, camera-ready National Security Aide Colonel Oliver North, a fount of “quote-ready” commentary heavy on convoluted descriptions of his relationship with the “man at the top,” Ronald Reagan. This commentary, in turn, functioned to distract from the suspicious pro-contra organizations and their sprawling network of funders described in Draper’s book.

Fifteen years later, the target was Iraq, and the players were Dick Cheney, then Vice President after a stint with a major war contractor, and Paul Wolfowitz, former Dean of the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins, pushing the Bush White House’s argument that “disarming Iraq of its chemical and biological weapons and dismantling its nuclear weapons program is a crucial part of winning the War on Terror.” The pliant reporters were Judith Miller and Elisabeth Bumiller of the New York Times, at the expense of the Times’ James Risen, whose skeptical reports were “back-paged,” a process he later characterized with as telling a description of 21st century establishment journalism as may yet exist: “It’s like any corporate culture, where you know what management wants, and no one has to tell you.”

Only later, when America was already in Iraq and no WMD was to be found, did the administration begin its explanatory turn, making “the intellectual argument” that “there is a war in Iraq and a war on terrorism and you have to separate them, but the public doesn’t do that”—as if the Administration hadn’t been the one pushing that very conflation on the public in the first place.

Fifteen years after that, the target was President Trump; the justification was Russian collusion; and the reporters included Bumiller, now Washington Bureau Chief for the New York Times, and Natasha Bertrand, who made her career beginning in 2017 off reporting intelligence leaks alleging Russia-Trump collusion from an FBI investigation that was riddled with problems from the start. Even the Washington Post had criticized Bertrand in February 2020 for the unquestioning way she pursued the Russia story in 2016. Interestingly, this was not a prominently featured point on or after October 19, 2020, when Bertrand broke news of the “Russian disinfo” letter.

Instead, by their own admission, reporters in October 2020 were busy blaming themselves for, and vowing not to repeat, what they saw as their real failure four years earlier: going against the dictates of “national security” by reporting on (genuine) emails leaked from the Clinton campaign by actors connected to Russia. In this context, these reporters’ willingness to accept Bertrand’s “Russian disinfo” claims despite her history and despite the October 19 letter’s actual text is the only way the Washington side of the “spies who lied” story could end.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

This is not representative government. Instead it’s a government within the government, predicated on the casual coordination of people who came up in the same institutions and rose through the same defense-and-intelligence agencies, law firms, contractors, press pools, and green rooms in Northwest Washington. These people know that, when they want to run an agenda, “plotting” is less necessary than a dropped hint or implication over the phone or dinner which can easily turn into a leaked letter powering lurid headlines they can deny later.

This government within a government may not be as far from Parks and Recreation and Space Force episodes and from Democratic imaginings as it may seem. After all, a tagline of the New York Times op-ed video in support of the deep state, between featurettes of friendly administrators at the Planetary Missions Program and the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Labor, is this: “The ‘deep state’ is hard at work making America great. Just because we don’t know about it doesn’t make it suspicious.”

The question for Americans is whether this shadow government allows us to make informed choices as citizens of a constitutional republic. For those of us who answer “No,” the follow-up question is whether, in 2024, we’ll let the deep state and its operators exercise their influence again.