Scientist who led mind-altering experiments on soldiers dies

By Harrison Smith / The Washington Post

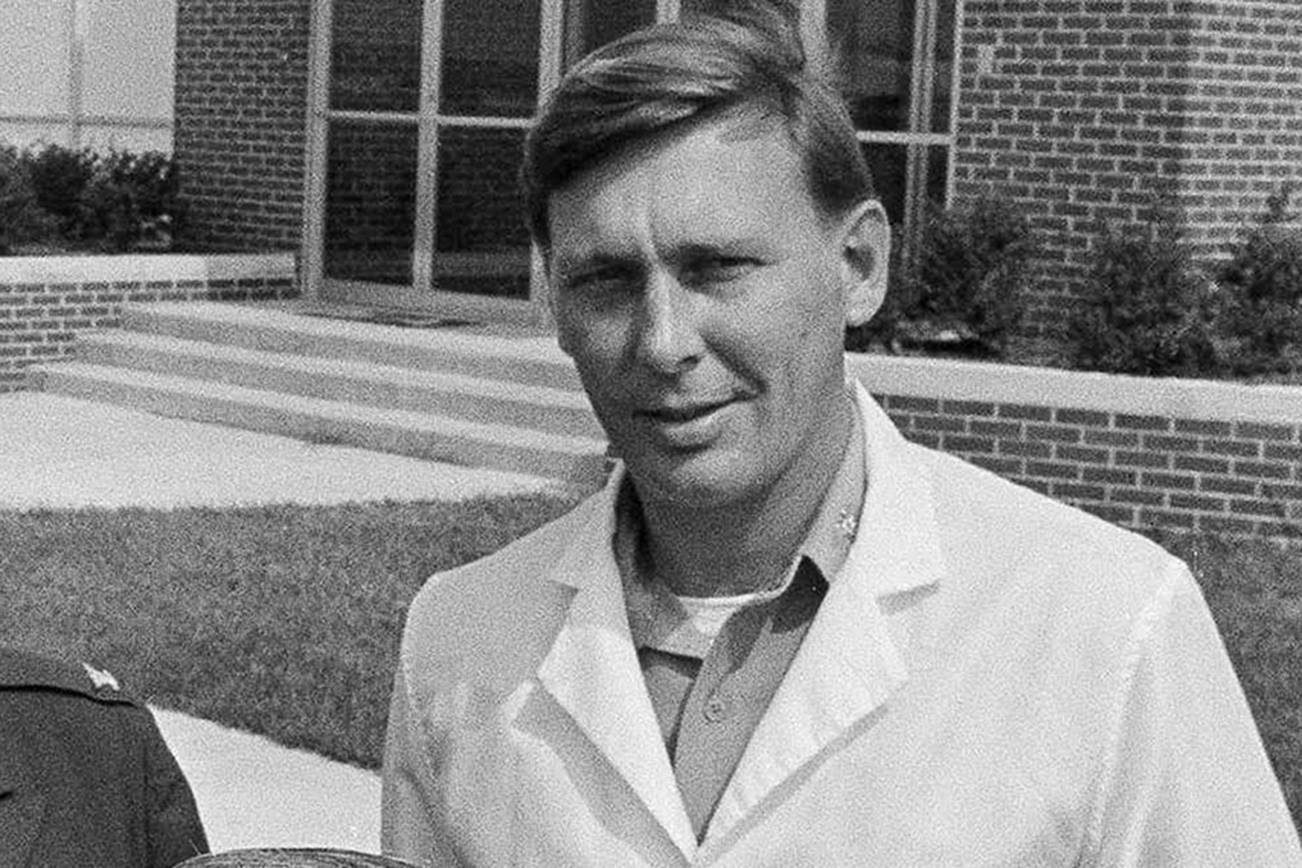

James Ketchum, an Army psychiatrist who studied the effects of LSD and other hallucinogenic drugs on American soldiers, overseeing classified Cold War-era experiments that spurred a debate on medical ethics, died May 27 at his home in Peoria, Arizona. He was 87.

His wife, Judy Ketchum, said she did not know the cause.

As American scientists raced to develop new missile systems in the 1960s, vying to outpace the Soviet Union in battlefield advances, Dr. Ketchum stood on the front lines of a parallel effort to modernize — some said civilize – human warfare.

“I was working on a noble cause,” he once said, according to a 2012 profile by New Yorker journalist Raffi Khatchadourian. “The purpose of this research was to find something that would be an alternative to bombs and bullets.”

In search of a so-called “war without death,” he and other Army researchers explored the use of mind-altering, nonlethal drugs, envisioning a day in which enemy combatants could be incapacitated by a breeze bearing psychedelics or a water supply tainted with LSD. Conducted from 1955 to 1975 at Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, the experiments echoed studies conducted through Project MKUltra, a CIA program that focused on the mind-control potential of drugs such as LSD.

Both initiatives were halted amid media reports and withering congressional hearings, during which the Edgewood project’s founder and director, Van Murray Sim, was criticized for failing to provide follow-up medical care for the 7,000 soldiers who participated as test subjects. An Army investigation found no evidence of deaths or “serious injury” as a result of the testing, although researchers later noted the possibility of long-term psychological effects.

For the most part, Ketchum was a fierce defender of the Edgewood studies and of “psychochemical warfare” more broadly — as when, in 2002, Russian authorities pumped a gas into a Moscow theater where Chechen militants had seized more than 700 hostages. The gas enabled Russian special forces to storm the theater but killed scores of innocents.

“It’s been looked at by some skeptics as a kind of tragedy,” Ketchum said, according to the New Yorker. “They say, ‘Look, 130 people died.’ Well, I think that 130 is better than 800, and it’s also better, as a secondary consideration, not to have to blow up a beautiful theater.”

Raised in New York City, with a literary bent and self-described “appetite for novelty,” Ketchum arrived at Edgewood in 1961 as a research psychiatrist amid reports that the Soviet Union was also developing robust chemical warfare capabilities. He rose to lead the arsenal’s pharmacology branch and clinical research department, designing and overseeing experiments on hundreds of healthy soldiers.

The research center tested toxic nerve agents such as VX and sarin gas, and some scientists conducted experiments that contributed to the development of bulletproof Kevlar vests and chemotherapy treatments for cancer. Ketchum specialized in drugs that caused delirium – throwing the mind into chaos, sometimes for several days – including phencyclidine, or PCP, and lysergic acid diethylamide, LSD.

Before his arrival, he said, the latter was occasionally tested on unwitting subjects: dropped into the coffee cup of a commanding officer at breakfast, mixed into cocktails at a party or added to an Army unit’s water supply. Ketchum insisted that he ended such practices and described his experiments as scarcely different from civilian drug tests.

His subjects volunteered through an Army recruitment program, but they were not told what they were given or how it would affect them, leading critics to insist that the experiments violated medical ethics by failing to obtain patients’ full consent.

Col. Douglas Lindsey, the arsenal’s chief medical officer, once declared that his volunteers were “not really informed at all.” Ketchum, by contrast, denied that subjects were “unwitting guinea pigs,” and in 2008 told the San Jose-area website Metroactive that his volunteers “performed a patriotic service.”

Soon after his arrival, Ketchum began focusing on 3-quinuclidinyl benzilate, or BZ, a white crystalline powder initially produced to treat ulcers. In small doses, it wreaked havoc on users, triggering a delirium in which patients exhibited obsessive behaviors, repeatedly fell down, experienced strange visions and more or less lost their minds.

Ketchum built padded cells for test subjects and, in one 1962 experiment, effectively created a Hollywood film set, constructing a makeshift “outpost” at which several soldiers were dosed with BZ, filmed by hidden cameras and ordered to prepare for an imminent chemical attack. In separate experiments, one subject tore down a panel of padding, “broke a wooden chair and smashed a hole in the wall,” according to notes kept by Ketchum. Another told him, “I feel like my life is not worth a nickel here.”

BZ was tested as a potential weapon, blown through wind tunnels to simulate a battlefield spray. But it proved difficult to control the size of doses and logistically challenging to administer — notably when Ketchum developed a plan, dubbed Project Dork, to disable the crews of Soviet trawlers sighted in 1964 off the coast of Alaska.

To test his proposal, a generator was used to produce a mist of BZ at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. The experiment was filmed by the Army, and Ketchum used the footage to direct a propaganda film, “Cloud of Confusion,” featuring ominous voice-over narration: “And on this desert this cloud was unleashed so men could measure the dimensions of its stupefying power.”

Project Dork failed to convince military leaders that BZ was worth using on the battlefield, however, and Ketchum left Edgewood for another Army post in 1971. He took many of the arsenal’s papers with him — a vast collection of documents that filled fireproof safes and boxes scattered across his home – and spent decades ruminating on his work, writing a memoir and weighing the duties of a doctor against those of a soldier.

“I struggle with these things,” he told the New Yorker. “But I have always had the feeling that I am doing more the right thing than the wrong thing.”

The older of two sons, James Sanford Ketchum was born in Manhattan on Nov. 1, 1931. His mother was a secretary, and his father was a telephone company manager who worked closely with Norman Vincent Peale, their church pastor and the author of “The Power of Positive Thinking.”

Ketchum received a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1952, graduated from medical school in 1956 at Cornell University and —tired of being broke and starting most days with “an old pickle jar half-filled with black coffee” for breakfast — joined the Army.

He initially worked at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and took a sabbatical from Edgewood in the mid-1960s to study at Stanford on a postdoctoral fellowship; while there, he also treated drug addicts at the Haight Ashbury Free Clinics. After resigning his colonel’s commission in 1976, he taught medicine at the University of Texas and the University of California at Los Angeles and worked at hospitals and clinics until retiring in the early 2000s.

His marriages to Joan O’Leary, Phyllis Pennington and Margot Turnbull ended in divorce. His marriage to Doris Fautheree was annulled, and in 1995 he married Judy Ann Schaller. In addition to his wife, survivors include a son, Kevin Ketchum, from his marriage to Fautheree; a daughter, Robin Ketchum, from his marriage to Turnbull; a brother; and a grandson. A daughter from his marriage to Fautheree, Laura, died in 2017.

Ketchum’s archives featured in a 2009 class-action lawsuit, filed by a veterans’ advocacy group on behalf of soldiers who participated in the chemical weapons testing program. In 2017, the U.S. District Court of Northern California ordered the Army to provide medical care to the surviving volunteers.

In his memoir, “Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten” (2006), Ketchum said that although he abstained from taking BZ, he was sometimes mystified by what he saw at Edgewood. One day, he said, he walked into his office to find a “large black steel barrel.” Inside were glass canisters filled with LSD — enough to intoxicate several hundred million people, by his estimate, and worth nearly $1 billion on the street.

Within a week, the barrel was gone. Ketchum said he never learned what it was for.

k

<!–

<!–

–>