Are COVID-19 conspiracy theories for losers? Probing the interactive effect of voting choice and emotional distress on anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Abstract

This study examines demographic and attitudinal determinants of belief in COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs in Poland and their impact on psychological well-being, social functioning, and adherence to public health measures over one year. A cross-sectional study with a retrospective component was conducted one year after the pandemic outbreak (N = 1000). A COVID-19 conspiracy belief factor, extracted via PCA, served as the dependent variable in hierarchical regression models. Changes in P-score (psychological distress), S-score (social functioning), WHO-5 score (well-being), and adherence to public health guidance were analyzed using t-tests. Key predictors of conspiracy belief included lower education, younger age, higher religiosity, and distrust in experts. Conspiracy believers (CTB) exhibited significantly higher P-scores (greater psychological distress) compared to non-believers (N-CTB). While S-score (social functioning) and WHO-5 score (well-being) declined in both groups over time, differences between CTB and N-CTB were not significant. Stronger conspiracy beliefs were associated with lower adherence to public health guidelines from the pandemic’s outset, with no significant improvement after one year. These findings confirm previous research linking conspiracy beliefs to reduced adherence to health measures and poorer psychological outcomes. However, they challenge assumptions that conspiracy beliefs necessarily impair well-being and social functioning over time. Strengthening institutional trust and addressing misinformation remain critical for improving public health compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories thrived in an environment of uncertainty, as the crisis was unprecedented, imposed significant societal restrictions, and generated cognitive dissonance due to inconsistent policy decisions. This period was also marked by an “infodemic” of misinformation1, with conspiracy narratives spreading widely alongside official health guidance. Conspiracy theories, broadly defined, attribute events to covert, intentional actions by powerful groups, often contradicting mainstream or official accounts2,3. From a social-psychological perspective, they serve cognitive, emotional, or social needs by offering simplified causal explanations that reinforce group identity and reduce uncertainty4,5. Epistemologically, they rely on selective evidence and skepticism toward institutional authority, often functioning as alternative belief systems resistant to falsification6,7. A minimal definition suggests that any explanation positing a conspiracy as the primary cause qualifies as a conspiracy theory, regardless of its truthfulness8. From a cultural perspective, conspiracy theories challenge dominant power structures and arise in response to social or political instability, often serving as counter-narratives to official discourses9,10. Despite their differences, these definitions converge on the idea that conspiracy theories frame events as the result of secret coordination by influential actors and reflect broader societal tensions surrounding trust, power, and uncertainty.

In Poland, endorsement of conspiracy beliefs appears to be associated with certain socio-demographic and ideological characteristics11 and the extent to which these patterns are consistent across nations remains a topic of ongoing research12. Although no country is immune to conspiracy beliefs, Poland’s socio-political context may intensify susceptibility to conspiracy thinking. As a post-communist society with a legacy of authoritarian rule and systemic surveillance, Poland has long struggled with low levels of institutional trust and social capital13. According to European Social Survey data, generalized trust and political trust in Poland remain among the lowest in Europe. In the most recent wave (2023/24), aggregated political trust—measured as the mean of trust in parliament, politicians, and political parties—reached only 3.3 in Poland, compared to 5.7 in Norway14. This persistent deficit of trust creates a sociocultural environment in which conspiracy beliefs are more likely to emerge and persist, serving both epistemic and symbolic functions in the face of perceived institutional illegitimacy15.

Empirical studies suggest that a propensity to endorse conspiracy beliefs may have a detrimental impact on mental well-being, social functioning, and overall life satisfaction over time16. Additionally, conspiracy beliefs have been linked to lower adherence to public health guidance, including vaccine uptake and compliance with preventive measures17,18.

Despite the clear link between conspiracy thinking and reduced guideline adherence19,20,21,22,23,24, there is a research gap in understanding the longer-term psychosocial and social impact of these beliefs, especially in Poland. Most early studies were cross-sectional or focused on short time spans, providing limited insight into how conspiracy believers’ attitudes and behaviors change as the pandemic progresses. We address this gap by examining a large Polish sample one year after the outbreak of COVID-19, utilizing a retrospective component to assess changes over time.

To explore the predictors of conspiracy beliefs, this study applies six hierarchical regression models based on prior research, covering demographic characteristics, economic status, media consumption, religiosity, trust in institutions, and attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic. Demographic factors such as age and education level have been found to influence susceptibility to conspiracy theories, with younger individuals and those with lower educational attainment showing higher endorsement rates25. Economic hardship has been associated with a greater inclination to adopt conspiratorial explanations for socio-political crises26. The role of media consumption, particularly social media, has been highlighted as a significant predictor of conspiracy belief, as misinformation spreads more rapidly through these platforms than traditional news sources27,28. Furthermore, diminished trust in government and mainstream media has been associated with a stronger endorsement of conspiracy beliefs¹⁴. Finally, attitudes toward the pandemic itself have fueled COVID-19-specific conspiracies, illustrating how crisis situations amplify existing conspiracy beliefs and encourage new ones4,29.

The aim of this study is to identify key demographic and attitudinal predictors of belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories and examine their long-term implications for psychological well-being and social functioning. Specifically, we compare believers and non-believers in terms of mental health outcomes (P-score), perceived social impact (S-score), changes in well-being (WHO-5 score), and adherence to Public Health Guidance from the onset of the pandemic to one year later.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This study draws upon data from two large-scale cross-sectional surveys conducted in Poland: The Collaborative Outcomes Study on Health and Functioning During Infection Times (COH-FIT) and The Rise or Fall? Short- and Long-term Health and Psychosocial Trajectories of the COVID-19 Pandemic (ROF) study. By integrating these two datasets, this research enables a multidimensional analysis of conspiracy beliefs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both studies incorporated a retrospective component, allowing respondents to compare their psychological and behavioral states before and during the pandemic. Additionally, the datasets include a wide array of variables informed by international research frameworks such as the European Social Survey (ESS). These encompass COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, economic status, institutional trust, media consumption patterns, religiosity, attitudes toward the pandemic, public health restrictions, and vaccination policies. The combined approach strengthens the study’s analytical depth, offering insights into the socio-psychological determinants of conspiracy beliefs within a broader political and economic context.

Sampling methodology

Both COH-FIT and ROF employed quota-based stratified sampling to ensure representativeness of the Polish adult population. Sampling quotas were based on demographic data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS) and stratified by gender, age, size of domicile, and regional representation across the 16 administrative regions of Poland. Participants were recruited through opinie.pl, the largest Polish internet panel with over 100,000 active respondents. The surveys were administered by IQS Group, a certified research agency associated with OFBOR (Polish Association of Public Opinion and Marketing Research Firms), ensuring compliance with ISO and PKJPA (Quality Control Program) methodological standards.

By integrating COH-FIT and ROF datasets, this study provides a robust framework for analyzing conspiracy beliefs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The combination of large-scale, representative cross-sectional data with retrospective self-assessments strengthens the validity of findings. Ethical approval for both studies was granted by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok, and participation was voluntary and anonymous. Detailed descriptions of sample distributions and methodological considerations are available in supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

ROF study

The ROF study was designed to complement COH-FIT by examining health and psychosocial trajectories in Poland. Conducted between March 12 and March 23, 2021, it surveyed 1,000 respondents who had previously participated in the COH-FIT study, enabling within-subject comparisons. The ROF questionnaire, informed by international and national research instruments, assessed changes in conspiracy beliefs, pandemic attitudes, and mental health over time. It followed the same rigorous methodological protocols and used the CAWI technique to ensure data consistency and quality.

Based on the ROF study, the ‘Adherence to Public Health Guidance’ measures were developed to assess the behavioral patterns of individuals prone and not prone to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories. This assessment was conducted at two time points: at the beginning of the pandemic and one year after its outbreak.

COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs

4 statements included in the ROF, incorporated from the European Social Survey to model conspiracy beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic, were asked30,31:

-

1.

‘The coronavirus (COVID-19) was created in a laboratory as a biological weapon’;

-

2.

‘Certain significant events have been the result of the activity of a small group who secretly manipulate world events’;

-

3.

‘Groups of scientists manipulate, fabricate, or suppress evidence in order to deceive the public’;

-

4.

‘The COVID-19 outbreak is the result of deliberate and covert efforts by some government or organization’.

The statements were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 ‘strongly disagree’, 2 ‘rather agree’, 3 ‘I neither agree nor disagree’, 4 ‘I rather agree’, 5 ‘I strongly agree’) (see supplementary Fig. 1&2).

The scale was measured for internal consistency using the Cronbach alpha test, which was 0.877, confirming its homogeneity with respect to the phenomenon under study.

Adherence to public health guidance

Indicators from the ROF tool were employed to investigate whether belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories influenced compliance with government-mandated public health measures, including social isolation, physical distancing, and mask-wearing. Adherence was assessed at two time points: (1) the onset of the pandemic in Poland (March 2020) – retrospective answer and (2) one year later (March 2021), allowing for an examination of temporal shifts in compliance behavior. The following behavioral indicators were included: ‘Avoidance of contact with others’ (0 – I do not avoid contact at all; 10 – I avoid contact at all times); ‘Maintaining a physical distance of 1.5 meters’ (0 – never; 10 – always); ‘Covering mouth and nose in public places’ (0 – never; 10 – always).

COH-FIT study

COH-FIT is a multinational initiative designed to assess the psychological and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic32. It collected representative data across 49 countries, including Poland, using an online survey. In Poland, a nationally representative sample of 2,500 adults aged 18 and older was recruited via quota-based stratified sampling. The study measured various psychological outcomes, including general well-being, stress, psychopathology, and coping mechanisms, in addition to factors related to pandemic-related misinformation and conspiracy beliefs. A validated Polish version of the COH-FIT questionnaire was employed, and data collection was conducted via computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) between March 5 and March 18, 2021. Findings from COH-FIT have already demonstrated significant declines in mental well-being and increased psychological distress during the pandemic32.

Based on the COH-FIT study, the Psychological & mental score (P-score)33, Social functioning score (S-score), and Well-being score (WHO-5 score) were developed, which serve as composite measures of psychological & mental distress and well-being.

Mental and psychological (P-score)

The P-score, developed as a composite measure of psychological vulnerability33,32 integrates key indicators reflecting emotional distress and cognitive-affective burden. It is derived from five subdomains: anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, and cognitive functioning, each assessed via a single-item self-report on a 0–100 Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), where higher values indicate greater symptom severity. Respondents rated the intensity of their symptoms on scales anchored at 0 (“not at all”) and 100 (“every day”) for each domain (e.g., “During the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems: Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge?”). The final P-score was computed as the arithmetic mean of the five VAS subscale scores. This composite index has been validated as a reliable measure of psychological distress in large-scale international research on mental health during the pandemic33 (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Social functioning (S-score)

The S-score, developed as a composite measure of social well-being and interpersonal functioning, captures key aspects of respondents’ family, social, and occupational dynamics. It comprises self-reported family functioning satisfaction, social functioning, and work-related functioning, each assessed on a 0–100 VAS scale, where higher scores indicate greater perceived satisfaction and effectiveness in these domains. Participants answered three questions: (1) “How satisfied are you with your family functioning?” (2) “How well are you able to function socially?” and (3) “How well are you able to function in your work or occupational role?”. All items were rated on VAS anchored at 0 (“not at all” or “unable to function”) and 100 (“fully satisfied” or “perfect functioning”). The S-score was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the three item scores.

Well-being (WHO-5 score)

The WHO-5 Well-being Index was employed as a measure of subjective psychological well-being, capturing respondents’ positive mood, vitality, and general life satisfaction. The original WHO-5 scale, which consists of five items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, was adapted to a 0–100 visual analogue scale (VAS) to maintain consistency with other indicators in COH-FIT and enhance respondent convenience. Each item was scored from 0 (never) to 100 (every day), with higher scores indicating greater well-being.

To ensure the validity and reliability of this adapted format, Warm’s Mean Weighted Likelihood Estimates (WLE) of Rasch Measures and Cronbach’s alpha were employed for scale reliability assessment. The WLE reliability formulas followed Adams (2005)34 (see Table 1). The conversion from the original 5-point Likert scale to a continuous 0–100 format did not compromise the reliability of the WHO-5 index, and subsequent analyses confirmed its measurement consistency and convergent validity. The standardized format allows for seamless integration within the broader COH-FIT framework, ensuring comparability across psychological and social dimensions assessed in the study.

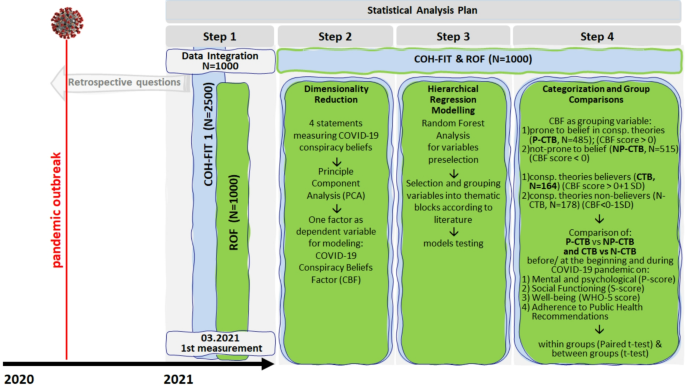

Statistical analysis plan

Comparative analyses were performed across key psychological and behavioral dimensions, including psychological vulnerability (P-score), social functioning (S-score), well-being (WHO-5 Score), and adherence to Public Health Guidance. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of how COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs relate to mental health, social relations, and compliance with preventive measures over time.

An R program with additional components for generating tables, graphs and statistics was used to conduct the analyses. List of packages used: haven, tidyverse, ggplot2, gtsummary, ggpubr, gmodels35,36,36,37,38,39.

To examine, using a representative sample and the conspiracy belief factor (CBF), who in Poland exhibits a greater propensity to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories and to analyze over time, with retrospective component, how the intensity of susceptibility to belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories influenced defined dimensions—P-score, S-score, WHO-5 score, and Adherence to Public Health Guidance—a multi-step analytical approach was implemented (see Fig. 1).

Step 1: Data Integration.

Data from the COH-FIT and ROF surveys were merged at the individual level to ensure a consistent sample of N = 1000 respondents who participated in both studies. This integration facilitated the comprehensive analysis of conspiracy beliefs across multiple dimensions.

Step 2: Dimensionality Reduction.

Four survey items measuring COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs were subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality and identify an underlying latent Conspiracy Belief Factor (CBF). The analysis yielded a single latent factor representing a unified dimension of conspiracy beliefs (see supplementary Fig. 3). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistic confirmed the adequacy of the data for PCA (see supplementary Table 3).

Step 3: Hierarchical Regression Modeling.

The extracted Conspiracy Belief Factor (CBF) was employed as the dependent variable in a hierarchical regression analysis. The models were constructed based on thematic structures identified in the literature to assess the predictive power of various sociodemographic, psychological, attitudinal, and worldview-related factors (e.g., trust, attitudes towards the pandemic, and vaccination). Six thematic models were tested in alignment with the study framework. Predictor selection was initially guided by a Random Forest analysis, ranking variables according to their impact on the dependent variable. The final model selection was refined through expert evaluation and a review of relevant literature. Population weights were applied to ensure national representativeness.

Step 4: Categorization and Group Comparisons.

To facilitate within- and between-group comparisons over time, the conspiracy belief factor (CBF) was dichotomized, enabling the construction of categorical variables. Specifically, the following classifications were established:

-

Prone to belief in COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories (P-CTB) vs. Non-Prone (NP-CTB): The mean (M = 0) of CBF served as the classification threshold: respondents with M > 0 were categorized as P-CTB (N = 485), whereas those with M < 0 were classified as NP-CTB (N = 515).

-

Conspiracy Believers (CB) vs. Non-Believers (N-CTB): A more stringent classification approach was applied using the three-sigma rule. Respondents with scores exceeding one standard deviation above the mean (M + 1SD) were categorized as CB (N = 164). Conversely, respondents with scores one standard deviation below the mean (M − 1SD) were classified as N-CTB (N = 178). This refined classification allowed for a more rigorous comparison of extreme groups in relation to COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (see supplementary Fig. 4).

These classifications provided a structured framework for assessing variations in belief patterns and their potential influence on predefined mental & psychological, social, well-being and attitudinal domains.

Results

Step 3. Hierarchical regression analysis of COVID-19 conspiracy determinants

To investigate the factors influencing belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted (see Tables 2 and 3). This approach allowed for a structured examination of how different sets of predictors contribute to variations in conspiracy beliefs. Successive models introduced additional categories of explanatory variables, progressively refining the understanding of their relative impact. The dependent variable in the analysis was a continuous factor score derived from Principal Component Analysis (PCA), summarizing responses to multiple conspiracy belief items into a single dimension. By adopting this method, we ensured that the regression models captured nuanced variations in belief strength rather than treating COVID-19 conspiracy belief as a binary outcome. In the models table the predictor labels are abbreviated, the full wording is included in the supplementary Table 5. Trust was derived through factor analysis (see supplementary Fig. 5 & supplementary Table 4), resulting in two distinct factors: (1) trust in institutions, including the European Union institutions, healthcare services (doctors), scientists, and private media called ‘Institutional Trust in International and Expert-Based Authorities’; and (2) trust in the government, the Ministry of Health, and public media, called’ Institutional Trust in National Authorities and State Media’.

Model 1: demographic factors

Model 1 focused on demographic predictors, explaining 7.7% of the variance (adjusted R2=0.072) (see Table 2). Gender was significantly associated with conspiracy beliefs, with men being less likely than women to endorse COVID-19 conspiracy believes (β=-0.159, 95% CI [-0.273, -0.044], p = 0.007). This represents a small but meaningful effect. Education also played a critical role, as individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher were significantly less prone to COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (β=-0.390, 95% CI [-0.543, -0.238], p < 0.001) compared to those with basic vocational education or lower. The size of this effect is moderate to large, underscoring the protective role of education. Age had a negative association with COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (β=-0.007, 95% CI [-0.010, -0.003], p = 0.001), indicating that younger individuals were more susceptible. Although statistically significant, the effect size is small, reflecting a gradual trend across age. Additionally, residing in a larger urban area (≥ 100,000 inhabitants) was linked to lower belief in COVID-19 conspiracy believes (β=-0.260, 95% CI [-0.403, -0.117], p < 0.001), suggesting that individuals from rural areas were more likely to endorse such narratives. This association is of moderate strength.

Model 2: economic factors

The inclusion of economic predictors in Model 2 slightly increased the explained variance to 9.6% (adjusted R2=0.089). A significant effect was observed for financial security, with respondents not worried about their household finances being less likely to adhere to COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (β=-0.264, 95% CI [-0.382, -0.146], p < 0.001). This represents a moderate effect, indicating that perceived financial stability plays a meaningful role in shaping belief orientations Although demographic predictors remained influential, the effect of male gender on COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs slightly decreased (β=-0.122, p = 0.033). This small effect suggests that economic context partly accounts for gender differences in conspiracy belief endorsement.

Model 3: media consumption

In Model 3, media engagement variables were introduced. The results indicated that individuals who consumed less TV news were more likely to endorse COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. This effect was statistically significant and of small-to-moderate size, suggesting that disengagement from traditional news may meaningfully increase susceptibility to misinformation. Furthermore, the amount of time spent online showed a marginal association with COVID-19 conspiracy belief susceptibility. While this effect was weaker and only marginally significant, it highlights the potential role of unregulated digital environments as vectors for conspiracy content. The explained variance increased to 11.5% (adjusted R2=0.106).

Model 4: religious beliefs

The fourth model added religiosity as a predictor (see Table 3), significantly increasing the explained variance to 22.5% (adjusted R2=0.214). A higher degree of religiosity was positively associated with COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (β = 0.024, 95% CI [0.005, 0.042], p = 0.011), confirming that more religious individuals were more likely to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy believes. Although statistically significant, the effect size was small, indicating that religiosity may contribute to conspiracy belief formation in a subtle but consistent manner. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that religious worldviews may foster a predisposition to interpret events through conspiratorial frameworks. Despite the introduction of this variable, the previously established effects of demographic and economic predictors remained consistent.

Model 5: trust in institutions

In Model 5, measures of institutional trust were incorporated, revealing that trust in international and expert-based authorities was the strongest negative predictor of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs (β=-0.333, 95% CI [-0.396, -0.269], p < 0.001). Respondents who exhibited greater skepticism toward scientists and international institutions were significantly more likely to endorse COVID-19 conspiracy believes. The effect size is moderate to large, highlighting the central role of institutional trust in shaping susceptibility to conspiracy narratives. This result underscores the centrality of distrust in shaping COVID-19 conspiracy belief systems, as individuals who reject expert opinions are more inclined to seek alternative explanations, including conspiratorial narratives.

Model 6: attitudes toward the pandemic

The final model (Model 6) integrated pandemic-specific attitudes, achieving the highest explained variance (adjusted R2=0.317, R2=32.9%). Negative attitudes toward COVID-19 (β=-0.084, 95% CI [-0.108, -0.061], p < 0.001) and unwillingness to vaccinate (β=-0.344, 95% CI [-0.467, -0.220], p < 0.001) emerged as strong predictors of COVID-19 conspiracy endorsement. The effect of vaccine hesitancy was particularly strong, suggesting a robust link between health-related mistrust and conspiracy thinking. Additionally, perceiving government restrictions negatively was associated with increased belief in COVID-19 conspiracy believes (β = 0.026, 95% CI [0.006, 0.046], p = 0.012). While this association was modest, it reinforces the notion that oppositional attitudes toward authority correlate with conspiratorial beliefs. In this comprehensive model, education level, trust in expert-based authorities, attitudes toward vaccination, and perceptions of the pandemic stood out as the most influential predictors. Notably, the gender effect diminished to marginal significance (β=-0.110, p = 0.039), suggesting that attitudinal variables may partly mediate gender differences in conspiracy belief. Time spent online became statistically significant (β = 0.008, p = 0.032), though the effect was small, indicating that digital exposure alone is a relatively weak but consistent predictor.This hierarchical regression analysis highlights the multifaceted nature of COVID-19 conspiracy belief formation in Poland, emphasizing the role of distrust, media exposure, religiosity, and demographic characteristics in shaping susceptibility to COVID-19 conspiracy believes.

Step 4. A within & between group comparison

Within- and between-group comparisons were conducted to assess changes over time in four key measures: P-score, S-score, WHO-5 Score, and Adherence to Public Health Guidance. Independent t-tests were used for between-group comparisons, whereas within-group differences were analyzed using paired t-tests.

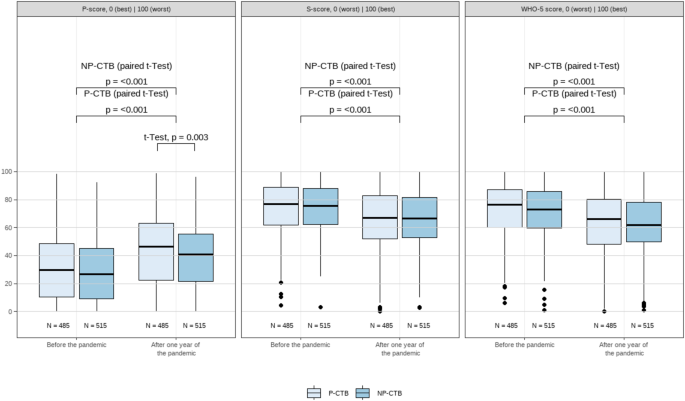

Figure 2 compares psychological distress (P-score), social functioning (S-score), and subjective well-being (WHO-5 score) before the COVID-19 pandemic and one year later, distinguishing between individuals prone to conspiracy beliefs (P-CTB) and those not prone (NP-CTB). All statistical details, including t-values, degrees of freedom, exact p-values, and Cohen’s d coefficients, are reported in supplementary Tables 6–7. Psychological distress (P-score) increased significantly over time in both groups (paired t-test, p < 0.001), with medium effect sizes: d = 0.528 for P-CTB and d = 0.506 for NP-CTB, indicating a substantial deterioration of mental health in both populations. Between-group comparisons after one year revealed a small but statistically significant difference (t(970) = -2.97, p = 0.003, d = 0.189), suggesting that P-CTB individuals experienced a moderately higher psychological burden, particularly in domains related to anxiety, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and cognitive fatigue.

Social functioning (S-score) declined significantly in both groups over time (paired t-test, p < 0.001), with small-to-moderate effect sizes (d = -0.362 for P-CTB; d = -0.407 for NP-CTB). However, no significant between-group differences were observed either before (d = -0.016) or after (d = 0.006) the pandemic’s first year, indicating relative stability and convergence in social and occupational engagement despite differing belief orientations.

Similarly, subjective well-being (WHO-5 score) significantly decreased across both groups (paired t-test, p < 0.001), with effect sizes of d = -0.447 for P-CTB and d = -0.487 for NP-CTB. The between-group differences remained non-significant (d = 0.065 after one year).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that while both groups experienced marked declines in psychosocial outcomes during the pandemic, P-CTB individuals exhibited slightly greater psychological deterioration, especially in mental distress domains. The magnitude of between-group differences remained generally small, underscoring the nuanced nature of conspiracy belief impacts.

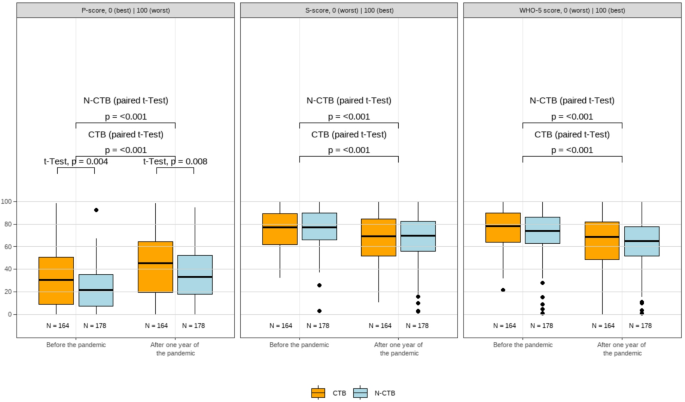

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in P-score, S-score and WHO-5 score between individuals who endorsed conspiracy beliefs (CTB) and those who did not (N-CTB). (see also supplementary Tables 8–9).

Psychological distress (P-score) increased significantly over time in both groups (p < 0.001), with medium effect sizes: d = 0.475 for CTB and d = 0.548 for N-CTB. Although the overall increase in distress was comparable, CTB individuals reported significantly higher levels of psychological burden both before (d = 0.316, p = 0.004) and after one year (d = 0.292, p = 0.008), indicating a consistent between-group disparity.

Social functioning (S-score) declined significantly over time in both groups (CTB: d = − 0.338; N-CTB: d = − 0.437; both p < 0.001), but no significant differences were observed between the groups either before (d = − 0.084, p = 0.437) or after one year (d = 0.015, p = 0.890), suggesting similar social resilience despite differing belief orientations.

Subjective well-being (WHO-5) also decreased significantly in both groups (CTB: d = − 0.479; N-CTB: d = − 0.474; both p < 0.001), with small and statistically non-significant between-group differences both at baseline (d = 0.187, p = 0.085) and follow-up (d = 0.129, p = 0.235).

These findings underscore a clear divergence between psychological symptoms and broader indicators of social functioning and well-being. While CTB individuals consistently reported more distress, their social and emotional functioning remained largely comparable to non-believers over time. This dissociation suggests that conspiracy beliefs may shape emotional strain without necessarily impairing everyday psychosocial functioning.

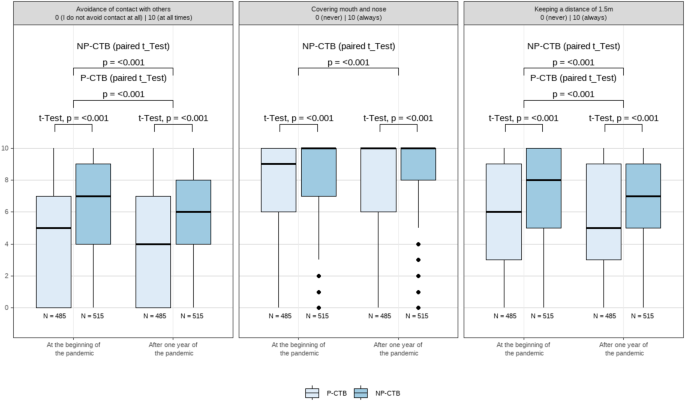

Figure 4 depicts how adherence to three public health behaviors varies between individuals prone to conspiracy beliefs (P-CTB) and those not prone (NP-CTB)., both at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and one year later. Detailed test statistics and effect sizes are available in supplementary Tables 10–11.

All three behaviors showed a statistically significant increase over time within both groups (p < 0.001), but the magnitude of change was small in all cases. For NP-CTB individuals, changes over time were modest: avoidance of contact (d = − 0.115), mask-wearing (d = 0.124), and physical distancing (d = − 0.149). P-CTB individuals showed even smaller within-group changes: avoidance (d = − 0.104), mask-wearing (d = 0.022, ns), and distancing (d = − 0.095), indicating minimal behavioral shift among this group.

Between-group differences were more pronounced. NP-CTB individuals reported significantly higher adherence across all behaviors both at baseline and follow-up. For avoidance of contact, effect sizes were moderate to large (d = − 0.500 at baseline; d = − 0.512 at follow-up). For mask-wearing, group differences increased over time (d = − 0.231 at baseline; d = − 0.331 at follow-up), and similar patterns were observed for physical distancing (d = − 0.431 at baseline; d = − 0.396 at follow-up).

These findings indicate that individuals prone to conspiracy beliefs were consistently less compliant with recommended public health measures. Moreover, while general adherence improved slightly over time, the between-group gaps persisted, suggesting that belief-related orientations substantially influenced behavioral responses throughout the pandemic.

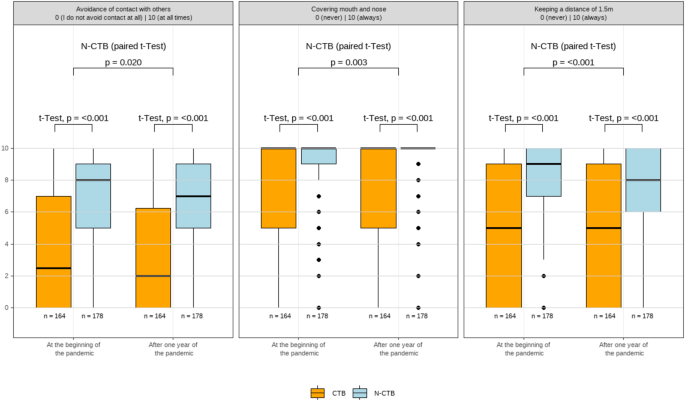

Figure 5 compares adherence to three public health measures among individuals endorsing conspiracy beliefs (CTB) and non-believers (N-CTB), before and one year after the COVID-19 outbreak. Statistical details are reported in supplementary Tables 12 and 13.

In the CTB group, adherence did not significantly change over time. Avoidance of contact (p = 0.547, d = − 0.025), mask-wearing (p = 0.646, d = 0.024), and physical distancing (p = 0.404, d = − 0.037) remained stable with negligible effect sizes. In contrast, the N-CTB group exhibited small but significant improvements: avoidance (p = 0.019, d = − 0.124), covering (p = 0.003, d = 0.194), and distancing (p < 0.001, d = − 0.205).

Between-group comparisons revealed large and persistent disparities. At baseline, CTB individuals were significantly less adherent: avoidance (d = − 0.908), mask-wearing (d = − 0.559), and distancing (d = − 0.918), all p < 0.001. These differences remained large after one year: avoidance (d = − 0.829), mask-wearing (d = − 0.743), and distancing (d = − 0.773), again all p < 0.001.

In sum, Fig. 5 underscores the strong and enduring behavioral gap between conspiracy belief endorsers and non-believers, with large effect sizes suggesting practical significance. While N-CTB individuals showed modest behavioral improvements, CTB individuals remained largely resistant to public health compliance.

Discussion

Conspiracy theories are represented everywhere and Polish society is not free from them either40. What varies from one cross-sectional study to another is the detail of the relevant variables presented in the results to explain the phenomenon of adherence to conspiracy theories, but which as a whole provide a consistent picture with the theoretical conceptualizations and findings of psychological research. Differences in the results of cross-sectional studies are sometimes due to sample selection, sample size, or, as others have argued, to various external factors (social context) unrelated to the personality of the individual: i.e. the level of democracy, the political system, the polarization of the political scene, the freedom of the media, the situational context consisting of who is currently in power – those who share the same ideology, or the opposition to ours41. Researchers agree, however, that their propagation is not without impact, both on the lives of the believers, but as a consequence of their actions, resulting from the conspiracy theories they profess, also on entire societies41.

The four-step statistical analysis allowed us to confirm many of the conclusions already found in the literature, but additionally enabled us to enrich the topic with extensive research material from which we were able to use predictors from a variety of topics for modelling: from economic to worldview (trust, religiosity), through attitudes towards vaccination and attitudes towards the social distancing obligation.

Our measurement, although pointwise, used a retrospective methodology, similar to Van Prooijen et al.41, by comparing the current intensity of the trait and then relating it to the pre-pandemic state. We are aware of the limitations of this method, which we describe in more detail in the limitations section. However, the possible biases resulting from the retrospective approach apply to both those inclined to believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories and those who do not believe in them, and therefore should not disproportionately affect only one of these groups.

Models summary

Hierarchical regression analysis reveals that COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs emerge from a complex interplay of sociodemographic, psychological, and attitudinal factors. The substantial increase in explained variance (7.7–32.9%) underscores the multidimensional nature of conspiracy belief formation, consistent with previous findings that structural and cognitive variables jointly shape susceptibility to misinformation and alternative societal explanations42,43,44.

Education consistently serves as a protective factor against conspiracy beliefs, with higher educational attainment linked to a lower likelihood of endorsing COVID-19 conspiracy theories. This finding aligns with previous research4,45, which demonstrates that as education levels increase, individuals become less likely to accept conspiracy-related statements as true.

Trust in scientific and international institutions emerges as a key determinant of susceptibility to conspiracy beliefs. Lower trust in scientists is strongly associated with increased endorsement of COVID-19-related conspiracy theories, consistent with previous research indicating that distrust in scientists and medical professionals fosters alternative explanatory frameworks rooted in misinformation19,20,41,46,47,48.

A robust association between vaccination reluctance and conspiracy beliefs raises significant public health concerns. Individuals endorsing conspiracy theories are markedly less likely to accept vaccines, reinforcing prior research showing that conspiracy thinking constitutes a substantial barrier to immunization29,49. Earnshaw et al. report43 that belief in COVID-19 conspiracies reduces vaccination intent nearly fourfold, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to counter misinformation. Similarly, Douglas et al.49, demonstrate that conspiracy narratives portraying vaccines as harmful hinder uptake.

Media consumption patterns significantly influence conspiracy belief endorsement. Disengagement from traditional news sources predicts higher susceptibility, suggesting that individuals avoiding mainstream information channels may be more vulnerable to misinformation50. This aligns with Jabkowski et al.12, who observe that lower consumption of traditional news correlates with greater belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories. While the effect of online exposure is marginally significant, digital environments remain a potential vector for misinformation, warranting further investigation.

In the Polish context, these media-related dynamics are embedded within a broader landscape of political polarization. The COVID-19 pandemic unfolded amid deep ideological divisions between the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party and the opposition Civic Platform (PO), with territorial patterns of support shaping both media consumption and institutional trust. Prior studies show that individuals who support opposition parties tend to endorse conspiracy theories more often when their party is out of power51. In Poland, this polarization was further reinforced by the state-affiliated media’s anti-European rhetoric during the pandemic.

Consistent with this, our findings demonstrate that higher trust in international and expert-based institutions—such as the European Union institutions, Healthcare services (doctors), Scientists, Private media (independent of government control)) —significantly reduces the likelihood of endorsing conspiracy theories17. This stands in contrast to the dominant narrative promoted by the ruling party’s media ecosystem those time, which frequently undermined EU institutions and framed external expert bodies as politically biased. These results suggest that institutional trust serves as a crucial protective factor against conspiracy thinking and should be a focal point for future interventions.

The relationship between religiosity and conspiracy beliefs requires nuanced interpretation. This aligns with previous research indicating that religious individuals are more likely than non-religious individuals to endorse conspiracy theories21,52. While religiosity does not directly predict conspiracy beliefs, it weakens the protective effect of education, suggesting that certain religious frameworks may facilitate conspiratorial thinking12. Studies have shown that religious fundamentalism can heighten skepticism toward science, potentially reinforcing conspiracy narratives12. Therefore, religious messaging during health crises should be carefully considered to mitigate misinformation while respecting faith-based perspectives. Poland remains a country with a high level of declared religiosity (71,3% Catholic according to the 2021 Census in comparison to 87,6% in 2011), though regular religious practice is declining—especially among youth, where it has dropped by almost 50% in the last 30 years53,54,55 This may be linked to institutional distrust, which replace traditional religiosity as drivers of conspiratorial thinking. Importantly, the decline of institutional religion does not necessarily liberate individuals from spiritual needs—rather, it often redirects them toward alternative frameworks such as supernaturalism, which has been shown to correlate with conspiracy thinking41,56,57.

Mental health, social functioning, and well-being

COVID-19 conspiracy believers reported higher levels of psychological distress (P-score), including increased anxiety, depression, and stress. These findings are consistent with previous cross-sectional studies showing that individuals endorsing conspiracy theories often experience heightened psychological burdens due to increased uncertainty and distrust50,58,59,60 similarly identified that conspiracy thinking is associated with reduced psychological resilience and elevated distress during the pandemic.

Our findings call into question the assumption that conspiracy beliefs inherently diminish well-being or impair social functioning over time. Although previous research has consistently linked conspiracy beliefs to increased distress, we provide novel evidence that subjective well-being (WHO-5) and social functioning (S-score) among conspiracy believers remain stable over time, even in the face of elevated psychological symptoms. This differs from earlier studies, such as van Prooijen16, which emphasized emotional costs but did not explore the divergence between distress and broader psychosocial functioning.

This dissociation between distress and well-being highlights an important contribution of our study. It suggests that conspiracy beliefs may not uniformly erode mental health, but instead interact with coping strategies or behavioral adaptations—such as non-compliance—to maintain subjective functioning. Additionally, conspiracy beliefs may function as a psychological coping mechanism, offering a sense of control in uncertain situations22. This may explain why, despite experiencing higher distress (P-score), conspiracy believers do not report significantly lower well-being. Similar effects have been observed in other crises, where belief in alternative narratives helps reduce existential anxiety17.

Furthermore, conspiracy theory believers (CTB) exhibited lower adherence to public health measures, consistent with prior findings linking conspiracy beliefs to reduced compliance17,61. Despite this, their well-being (WHO-5) and social functioning (S-score) remained stable, suggesting that non-compliance may have compensated for pandemic-related distress. Defying restrictions could have preserved social interactions and autonomy, buffering against loneliness and psychological decline62,63. These findings suggest a potentially underexplored pattern of paradoxical stability in well-being among conspiracy believers, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of how belief systems may intersect with psychosocial outcomes in a national context.

Future research should explore whether resistance to health measures mitigated the adverse effects of pandemic-related isolation and stress.

These results highlight a crucial gap in the literature: while the psychological distress associated with conspiracy beliefs is well-documented, longitudinal studies on well-being and social functioning remain limited. The assumption that conspiracy believers experience long-term declines in well-being lacks robust empirical support. Future research should investigate moderating variables such as social identity, coping strategies, and cultural differences to better understand why some conspiracy believers maintain stable well-being. Furthermore, examining whether specific subgroups of conspiracy believers—such as those with stronger institutional distrust—are more vulnerable to well-being declines would be an important avenue for further study.

Adherence to public health guidance

Consistent with prior research, we observed that conspiracy believers were significantly less likely to comply with public health measures, including social distancing, mask-wearing, and avoiding close contact17,19,20,21,23,24. Cross-sectional studies from multiple countries (e.g., Poland, UK, USA) have shown that COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs strongly predict reduced adherence to preventive behaviors19,29. Notably, our findings indicate that while overall compliance improved over time, the gap between conspiracy believers and non-believers persisted or even widened. This aligns with longitudinal evidence that those who endorsed conspiracies early in the pandemic showed slower behavioral adaptation to health guidelines64. Vaccine hesitancy was also significantly higher in conspiracy believers, confirming previous findings that misinformation fuels distrust in medical interventions20.

Limitations

Although by carrying out two extended surveys (COH-FIT & ROF) on the same population we were able to gather extensive research material, the results obtained have some limitations. Firstly, our study was cross-sectional and, as pointed out by De Coninck et al.50, this means that the results should not be interpreted as causal but as correlational. Establishing causality is possible with longitudinal studies i.e. with at least three time points65. Secondly, the retrospective method we used after one year of the pandemic COVID-19 in Poland, where we asked respondents about their feelings ‘during the last two weeks’ and ‘for a fortnight of regular life before the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak’ may have influenced the declared level of values of variables built referentially to an individual’s current psychosocial state and biased the data. It is worth noting, however, that the retrospective method is widely used, particularly in cohort studies, as it allows for the comparison of respondents’ subjective assessments with their clinical performance, providing valuable insights into psychosocial changes. Nevertheless, this approach may be subject to recall bias, which could influence the accuracy of self-reported data. Retrospective methods, like any research approach, have both strengths and limitations. In the case of an event such as the COVID-19 pandemic, strict lockdown measures and the lack of systematic access to respondents for conducting assessments, including medical evaluations, made retrospective data collection the only viable alternative for capturing conditions both prior to and during the pandemic. Recent methodological research also highlights that recall bias may operate differentially across subgroups in observational designs—particularly when respondents’ prior beliefs shape memory reconstruction—posing an additional consideration for group-level comparisons66 These retrospective issues are discussed in the work of L. Hipp et al.67, which provides a statistical analysis of the impact of retrospective questions on the obtained results. As the authors note, despite their limitations „.even though data elicited using retrospective questions [.]they are pretty consistent at the aggregate level” (see also Jaspers et al.68. Therefore, although the influence of current well-being on retrospective responses may occur, it does not necessarily bias the results unequivocally.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the significant role of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs in shaping public health behaviors, mental health, and social functioning. The findings reinforce that individuals who endorse conspiracy theories exhibit increased psychological distress (P-score), lower adherence to public health measures, and heightened distrust in institutions. Importantly, the observed associations were accompanied by small-to-moderate effect sizes for mental health outcomes, and large effect sizes for behavioral non-compliance, indicating that the practical implications of conspiracy beliefs are particularly pronounced in the behavioral domain. Stability in WHO-5 and S-score outcomes among conspiracy believers suggests that defiance of public health directives may have served as an adaptive mechanism, providing a sense of agency and buffering pandemic-related distress. This interpretation should be viewed cautiously, as the observational nature of the data does not allow for causal inference. These findings emphasize the importance of distinguishing psychological distress from subjective well-being when analyzing the impact of belief systems.

The persistence of conspiracy beliefs over time underscores the need for targeted public health strategies. Rather than prescriptive solutions, our findings suggest that interventions targeting institutional trust may hold potential for improving public health compliance among groups prone to conspiracy beliefs. Research suggests that preemptive fact-checking, transparent communication, and engagement with trusted community leaders can help mitigate the spread of conspiracy theories and improve adherence to health guidelines. Additionally, tailored mental health support for individuals affected by pandemic-related misinformation is crucial.

Importantly, our results show that trust in international and expert-based institutions—such as the European Union, healthcare services (doctors), scientists, and private media —was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of endorsing conspiracy beliefs. This highlights the need to actively counter politicized narratives that undermine such institutions, particularly in polarized contexts.

Moving forward, future research should adopt a longitudinal approach to further examine the causal relationships between conspiracy beliefs, well-being, and public health behaviors. Given the magnitude and persistence of behavioral gaps identified in this study, longitudinal methods will be essential for disentangling short-term reactive behaviors from long-term attitudinal change. Investigating the role of social identity, cognitive coping mechanisms, and cultural variations in conspiracy thinking may provide deeper insights into the resilience of these beliefs. Additionally, exploring whether specific subgroups—such as those with pronounced institutional distrust—are at higher risk for long-term adverse outcomes will be essential for developing effective interventions.

Addressing conspiracy beliefs requires a multidisciplinary effort that integrates psychological insights, evidence-based communication strategies, and policy initiatives aimed at strengthening public resilience against misinformation in future crises. By fostering a more informed and trust-based relationship between the public and health authorities, societies can enhance their preparedness for future public health challenges.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection reasons and proprietary rights within the global consortium and the fact that the ROF project is still ongoing and new data is being collected., but are available from the correspondence author upon reasonable request.

References

-

Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 395, 676 (2020).

-

Sunstein, C. R. & Vermeule, A. Conspiracy theories: causes and cures**. J. Political Philos. 17, 202–227 (2009).

-

Keeley, B. L. Of conspiracy theories. J. Philos. 96, 109 (1999).

-

Van Prooijen, J. W. & Douglas, K. M. Conspiracy theories as part of history: the role of societal crisis situations. Memory Stud. 10, 323–333 (2017).

-

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (un-)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. Eur. J. Pers. 28, 25–43 (2014).

-

Brotherton, R. Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories (Zed Books, 2021). https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472944528

-

Lewandowsky, S., Oberauer, K. & Gignac, G. E. NASA faked the Moon Landing—Therefore, (Climate) science is a hoax: an anatomy of the motivated rejection of science. Psychol. Sci. 24, 622–633 (2013).

-

Conspiracy Theories: The Philosophical Debate. (Routledge, 2019). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315259574

-

Fenster, M. Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

-

Husting, G. & Orr, M. D. Machinery conspiracy theorist as a transpersonal strategy of exclusion. Symbolic Interact. 30, 127–150 (2007).

-

Duplaga, M. The determinants of conspiracy beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of internet users. IJERPH 17, 7818 (2020).

-

Jabkowski, P., Domaradzki, J. & Baranowski, M. Exploring COVID-19 conspiracy theories: education, religiosity, trust in scientists, and political orientation in 26 European countries. Sci. Rep. 13, 18116 (2023).

-

Sztompka, P. Trust: A Sociological Theory (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

-

Political Trust in the European Social Survey. Encompass. https://encompass-europe.com/comment/political-trust-in-the-european-social-survey (2025).

-

Ferreira, S. et al. What drives beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories? The role of psychotic-like experiences and confinement-related factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 292, 114611 (2022).

-

Van Prooijen, J. W., Etienne, T. W., Kutiyski, Y. & Krouwel, A. P. M. Conspiracy beliefs prospectively predict health behavior and well-being during a pandemic. Psychol. Med. 53, 2514–2521 (2023).

-

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. A. Bioweapon or a hoax?? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 11, 1110–1118 (2020).

-

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel: the System-Justifying function of conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 39, 465–478 (2018).

-

Bierwiaczonek, K., Kunst, J. R. & Pich, O. Belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Appl. Psych Health Well. 12, 1270–1285 (2020).

-

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. The social consequences of conspiracism: exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 105, 35–56 (2014).

-

Oliver, J. E. & Wood, T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the united States. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 817 (2014).

-

Hornsey, M. J. et al. To what extent are conspiracy theorists concerned for self versus others? A COVID-19 test case. Euro. J. Social Psych. 51, 285–293 (2021).

-

Bird, S. T. & Bogart, L. M. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV/AIDS and birth control among African Americans: implications for the prevention of HIV, other stis, and unintended pregnancy. J. Soc. Issues. 61, 109–126 (2005).

-

Gillman, J. et al. The effect of conspiracy beliefs and trust on HIV diagnosis, linkage, and retention in young MSM with HIV. Hpu 24, 36–45 (2013).

-

Uscinski, J. E., Klofstad, C. & Atkinson, M. D. What drives conspiratorial beliefs?? The role of informational cues and predispositions. Polit. Res. Q. 69, 57–71 (2016).

-

Goertzel, T. Belief in conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 15, 731 (1994).

-

Marwick, A. & Lewis, R. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.

-

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D. & Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 359, 1146–1151 (2018).

-

Romer, D. & Jamieson, K. H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 263, 113356 (2020).

-

https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/COVID-19-Conspiracy-Beliefs.pdf (2024).

-

Round 10 COVID-19 Questions Finalised | European Social Survey. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/news/article/round-10-covid-19-questions-finalised.

-

Solmi, M. et al. The collaborative outcomes study on health and functioning during infection times in adults (COH-FIT-Adults): design and methods of an international online survey targeting physical and mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 393–407 (2022).

-

Solmi, M. et al. Validation of the collaborative outcomes study on health and functioning during infection times (COH-FIT) questionnaire for adults. J. Affect. Disord. 326, 249–261 (2023).

-

Adams, R. H. & Page, J. Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Dev. 33, 1645–1669 (2005).

-

Wickham, H., Miller, E. & Smith, D. Haven: Import and Export ‘SPSS’, ‘Stata’ and ‘SAS’ Files. (2023).

-

Kassambara, A. ggpubr ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. (2023).

-

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open. Source Softw. 4 (2019).

-

Lüdecke, D. Tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J. Open. Source Softw. 3, 772 (2018).

-

Sjoberg, D., Whiting, D., Curry, K., Lavery, M., Larmarange, J. & J., A. & Reproducible summary tables with the Gtsummary package. R J. 13, 570 (2021).

-

De Golec, A. & Cichocka, A. Collective narcissism and anti-Semitism in Poland. Group. Processes Intergroup Relations. 15, 213–229 (2012).

-

Van Prooijen, J., Douglas, K. M. & De Inocencio, C. Connecting the Dots: illusory pattern perception predicts belief in conspiracies and the supernatural. Euro. J. Social Psych. 48, 320–335 (2018).

-

Georgiou, N., Delfabbro, P. & Balzan, R. COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and their relationship with perceived stress and pre-existing conspiracy beliefs. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 166, 110201 (2020).

-

Earnshaw, V. A. et al. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Translational Behav. Med. 10, 850–856 (2020).

-

Banerjee, D. & How COVID-19 is overwhelming our mental health. Nat. India. https://doi.org/10.1038/nindia.2020.46 (2020).

-

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Callan, M. J., Dawtry, R. J. & Harvey, A. J. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Think. Reason. 22, 57–77 (2016).

-

Swami, V. et al. Conspiracist ideation in Britain and Austria: evidence of a Monological belief system and associations between individual psychological differences and real-world and fictitious conspiracy theories: conspiracist ideation. Br. J. Psychol. 102, 443–463 (2011).

-

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M. & De Zavala, A. G. Does Self-Love or Self-Hate predict conspiracy beliefs?? Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and the endorsement of conspiracy theories. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 7, 157–166 (2016).

-

Wahl, I., Kastlunger, B. & Kirchler, E. Trust in authorities and power to enforce tax compliance: an empirical analysis of the slippery slope framework: TRUST IN AUTHORITIES AND POWER. Law Policy. 32, 383–406 (2010).

-

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M. & Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 538–542 (2017).

-

De Coninck, D. et al. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front. Psychol. 12, 646394 (2021).

-

Lin, F., Meng, X. & Zhi, P. Are COVID-19 conspiracy theories for losers? Probing the interactive effect of voting choice and emotional distress on anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1–12 (2025).

-

Lahrach, Y. & Furnham, A. Are modern health worries associated with medical conspiracy theories? J. Psychosom. Res. 99, 89–94 (2017).

-

GUS. stat.gov.pl Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna i ekonomiczna ludności Polski w świetle wyników NSP. https://stat.gov.pl/spisy-powszechne/nsp-2021/nsp-2021-wyniki-ostateczne/stan-i-struktura-demograficzno-spoleczna-i-ekonomiczna-ludnosci-polski-w-swietle-wynikow-nsp-2021,6,2.html (2025).

-

ISKK. Ilu jest Katolików W Polsce? Seminarium i Raport ISKK. Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC. https://iskk.pl/ilu-jest-katolikow-w-polsce-raport-iskk/ (2024).

-

GUS. Rocznik Demograficzny stat.gov.pl. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-demograficzny-2023,3,17.html (2023).

-

Dagnall, N., Denovan, A., Drinkwater, K. G. & Escolà-Gascón, Á. Paranormal belief and conspiracy theory endorsement: variations in adaptive function and positive wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 16, 1519223 (2025).

-

Hart, J. & Graether, M. Something’s going on here: psychological predictors of belief in conspiracy theories. J. Individual Differences. 39, 229–237 (2018).

-

Freeman, D. et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 52, 251–263 (2022).

-

Grzesiak-Feldman, M. The effect of High-Anxiety situations on conspiracy thinking. Curr. Psychol. 32, 100–118 (2013).

-

Swami, V. et al. Putting the stress on conspiracy theories: examining associations between psychological stress, anxiety, and belief in conspiracy theories. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 99, 72–76 (2016).

-

Pummerer, L. et al. Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 13, 49–59 (2022).

-

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 united Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 265, 113521 (2020).

-

Martela, F. & Ryan, R. M. Prosocial behavior increases well-being and vitality even without contact with the beneficiary: causal and behavioral evidence. Motiv Emot. 40, 351–357 (2016).

-

Van Prooijen, J. & Song, M. The cultural dimension of intergroup conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 112, 455–473 (2021).

-

Ployhart, R. E. & MacKenzie, W. Jr. I. Two waves of measurement do not a longitudinal study make. In More Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends. 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110391814 (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2015).

-

Bong, S., Lee, K. & Dominici, F. Differential recall bias in estimating treatment effects in observational studies. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2307.02331 (2023).

-

Hipp, L., Bünning, M., Munnes, S. & Sauermann, A. Problems and pitfalls of retrospective survey questions in COVID-19 studies. Surv. Res. Methods. 14, 109–114 (2020).

-

Jaspers, E., Lubbers, M. & Graaf, N. D. Measuring once twice: an evaluation of recalling attitudes in survey research. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 25, 287–301 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Ł.K, P.S. P.L.; methodology, Ł.K, P.S., P.L., A.M.M, K.K.; sofware, Ł.K., P.S., P.L., M.A.; validation, Ł.K., P.S., P.L., M.A., A.M.M., K.K.; formal analysis, Ł.K, P.S., P.L., M.A; investigation, Ł.K, P.S., P.L., M.A, A.M.M, Ł.Sz., S.S., K.K, K.Ż., J.S, M.S, Ch.C., T.T., A.E.; resources, Ł.K, P.S., P.L., M.A, A.M.M, Ł.Sz., S.S., K.K, K.Ż., J.S, M.S, Ch.C., T.T., A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, Ł.K, P.S, P.L., M.A., writing—review and editing, A.M.M, Ł.Sz., S.S., K.K, K.Ż., J.S, M.S, Ch.C., T.T., A.E.; visualization, Ł.K., P.S.,P.L.,M.A., supervision, Ł.K. K.K., M.S, Ch.C.; project administration, K.K., M.S, Ch.C. funding acquisition, Ł.K., P.S., K.K., K.Ż., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiszkiel, Ł., Sowa, P., Laskowski, P.P. et al. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs in Poland. Predictors, psychological and social impact and adherence to public health guidelines over one year.

Sci Rep 15, 16274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99991-w

-

Received: 17 May 2024

-

Accepted: 24 April 2025

-

Published: 10 May 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99991-w