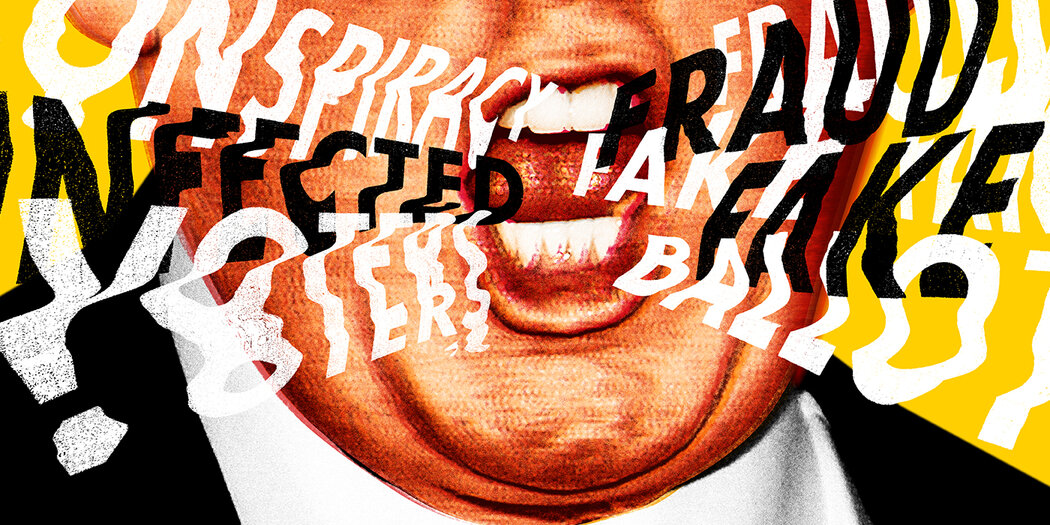

Refuting the Myth of Voter Fraud Yet Again

Election officials and experts have long been clear: voter fraud is exceedingly rare. Nonetheless, President Trump and his enablers have repeatedly made baseless claims of massive voter fraud for years, most recently as part of their fruitless attempts to overturn the presidential election. Those efforts have been rebuked by federal government agencies, scores of state and local Republican election officials, and dozens of courts (including Trump-appointed judges).

None of that has stopped Trump’s brazen attempts to subvert the will of American public. In a phone call last Saturday, he pressured Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, to “find 11,780 votes” in order to reverse the outcome in the state — a move that legal experts have condemned as a flagrant abuse of power.

What can we make of Trump’s repeated claims of voter fraud?

The president’s claims of widespread voter fraud are not just unsubstantiated — they are flat-out false, and have been repeatedly and definitively debunked by scores of the nation’s leading election administrators, national security leaders, political leaders, and election experts. Indeed, the top federal agencies in charge of election security issued a joint statement declaring that the November 3 election was “the most secure in American history” and that there was “no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.”

Since November, Trump and his allies have had ample time to provide evidence of voter fraud across the country but have been unable to do so. They have filed more than 60 lawsuits challenging the results of the November election and have lost all but one. Judges have unanimously rebuffed Trump’s claims of fraud as unfounded and contrary to evidence, including judges appointed by Trump and other Republican presidents. Trump’s fraud claims were so outrageous that several courts went so far as to denounce the ethics of the lawyers who filed them and expressed incredulity at the relief they sought — namely, to disenfranchise hundreds or even millions of voters. Trump fared no better in the lead up to Election Day, when he filed more than a dozen lawsuits predicting that the election would be marred by fraud. Courts rejected every one of those claims.

These latest attempts are consistent with more than four years of peddling lies about widespread voter fraud by Trump, who even challenged the integrity of the 2016 election, which he won. The commission he established in 2017 to prove the existence of fraud shuttered in scandal after finding no such fraud. His efforts in 2020 have failed even more spectacularly — and have made clear that his claims were no more than a pretext to disenfranchise millions of voters and steal an election.

How well-run was the election in Georgia based on what we saw both on Election Day in November and in the subsequent audit and recount processes?

The election was extremely well-run in Georgia, which is particularly remarkable given that the election was conducted in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Georgia was able to accomplish this, firstly, because the state invested in increased pay for poll workers to make sure that plenty of polling sites would be available and that they could keep crowding to a minimum. Local jurisdictions bought extra emergency paper ballots in case of machine glitches. Voters, too, played a part. They planned ahead and voted early when possible to reduce the burden on Election Day polling places. They requested and mailed their ballots in early or used secure drop boxes to ensure their ballots would be received in time to count. Just a week after experiencing a Covid-19 outbreak in their elections warehouse, workers in Fulton County, as well as across the state, logged multiple nights of late hours to ensure that all ballots were scanned quickly and results released as promptly as possible.

Last but not least, for the first time in several decades, Georgia conducted a statewide general election in which all votes were cast on paper. That’s because in 2020, Georgia finally replaced its antiquated and paperless voting systems — which security experts had long found were insecure — with new machines that produced a paper record of each vote.

Election Day was followed by a full canvass of these votes (which means, among other things, comparing the number of voters who signed in at the polls or requested and returned mail ballots with the total number of votes reported), and then a full recount of every one of the nearly 5 million paper ballots. Georgia completed that full process twice: once by hand and once by machine.

In short, there has probably never been an election in Georgia that has involved so much work both in preparation and to reconfirm the results.

In a recent phone call, Trump pressured Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, to “find” enough votes to overturn his defeat. Historically speaking, where does this rank as a presidential abuse of power?

This undoubtedly ranks as one of the most egregious abuses of presidential power in the history of the republic. Never before has a sitting president attempted to use his power to try to overturn the result of an election he lost. Not only did Trump threaten a public official to try to get him to violate the law, but he did so in an attempt to subvert the democratic process — the very foundation of our political system and the president’s authority.

This incident is part of a broader pattern of conduct by Trump that includes his notorious 2017 conversation with the president of Ukraine, an incident that led to Trump’s impeachment. Then, too, he threatened to use the powers of the presidency (to withhold U.S. aid granted by Congress) unless Ukraine helped him politically (by supporting his efforts to undermine the investigation into Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and launching a criminal investigation of Hunter Biden). Trump has also repeatedly tried to shut down the Russia probe and to pressure the Department of Justice to take myriad actions to benefit his allies and punish his political adversaries.

Did voting machine companies founded by Hugo Chávez play a decisive role in the 2020 election?

Trump’s allies have attempted to link Dominion Voting Systems, a company that makes voting machines used in several Georgia counties and in jurisdictions across the United States, with the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. They have claimed that Dominion used software from another voting machine company, Smartmatic, and that the latter company was founded by Chávez to fix elections. These claims are unfounded and categorically false. These companies are not connected to the Venezuelan government, nor did they or any voting machine company interfere in the 2020 general election.

First, while the founders of Smartmatic are Venezuelan, the company was founded in Florida, incorporated in the United States, and is now headquartered in London, and there is no evidence that the company has any relationship with governments or political parties in Venezuela or elsewhere. The families of Antonio Mugica and Roger Piñate, Smartmatic’s founders, hold the majority of the company’s shares. Furthermore, Smartmatic’s involvement in the 2020 U.S. general election was limited. As the New York Times reports, aside from a contract with Los Angeles County, the company was not involved in the 2020 general election. Smartmatic has stated that none of the systems it provided counted, tabulated, or stored votes.

Similarly, there is no evidence that Dominion has any corporate ties with Venezuela. In response to a request by the House Committee on Administration, Dominion CEO John Poulos stated in an April 2020 letter that approximately 75 percent of the company was owned by Staple Street Capital, a New York City-based private equity firm; that Poulos himself, a Canadian citizen, held a 12 percent stake; and that no other investor held more than a 5 percent stake. It should be noted that these numbers are reported by a privately owned company and as a result are not independently verifiable. The Brennan Center has called for greater transparency when it comes to the ownership or control of election system vendors. Nonetheless, any claims of ties between Dominion and the Venezuelan government remain unsubstantiated.

Importantly, there is also no evidence that Dominion voting machines used Smartmatic software during the November election, and both companies have stated that they have no business relationship.

Trump has cited, among other things, a report that claims it uncovered significant tabulation errors in Antrim County, Michigan. Did glitchy voting machines throw off the vote counts in battleground states?

As with any technology, it is important to double (and triple) check results reported by voting systems, which are prone to occasional human and technical errors and malfunctions. That’s why it’s so important to have paper ballots, a postelection canvass, and post-election audits that allow election officials to check, verify, and if necessary, correct initial unofficial election results.

In Antrim County, human error led to mistakes in entering initial vote tallies. The county clerk caught the error and fixed it the next morning, before initial results were finalized. These results were later confirmed in a postelection audit, which included a hand recount of every single vote for president.

More generally, it’s worth noting that in the three states where Trump supporters plan to contest election results in Congress — Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania — there were paper ballots for every single vote. All of these states have conducted postelection audits comparing paper ballots with the machine totals.

What kind of effects do repeated voter fraud claims have on American democracy? What can or should be done to set the record straight?

After January 20, the United States will have to grapple with whether and how to best ensure Trump is held accountable for his persistent abuses of presidential power. But it is not enough to look backwards: the country also needs to shore up the guardrails against presidential overreach in order to prevent similar abuses in future administrations. Congress can start by passing the Protect Our Democracy Act and adopting the other recommendations made by the bipartisan National Task Force on Rule of Law and Democracy. For its part, the incoming administration can adopt constraints to ensure the rule of law and ethical governance.

Congress can also act to strengthen voting rights and the electoral counting system to ensure that there are no more loopholes that unscrupulous candidates can exploit to disenfranchise eligible voters. The best ways for Congress to start are by passing the For the People Act (H.R. 1), which would guarantee every American fair voting access; by passing the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would shore up protections against discrimination in the voting process; and by upgrading the byzantine Electoral Count Act, which governs how electoral votes are cast and counted.