The Evolution of Terror: 6 Critical Threats 19 Years After 9/11 – Homeland Security Today

When the planes hit the Twin Towers, the Pentagon and a field in Shanksville, Pa., 19 years ago, it wasn’t the beginning of the war on terror but the advent of a more public-facing chapter in the global terror fight. After all, al-Qaeda left its calling card on the World Trade Center in 1993, killing seven and injuring more than a thousand people with a bomb in the underground parking garage. It wasn’t until 2001, though, that the terror group tried to take down the towers again — with an evolved and expanded plan that, over three locations, took 2,977 lives and injured thousands more.

In terrorist circles that now reach into every corner of the world via mountains of online propaganda and open-source tactic tutorials, the 9/11 attacks are still hailed as a gold standard of sorts — even ISIS propaganda periodically invokes al-Qaeda’s handiwork that day with 9/11 imagery while promising to similarly attack the United States. But as tactics evolved from the first World Trade Center bombing to the second, so have terror groups, independent cells, and lone extremists grown and evolved through mixing psychological and physical warfare, drawing from a diverse recruitment pool, moving operations including training into the virtual realm, picking softer targets and simple weapons that may inflict lower casualty counts but produce attacks that are harder to detect in the planning stages and cheaper to conduct, focusing on cyber operations and offering tech support to followers communicating online, and disseminating an endless stream of online materials that inspire, recruit, incite, and teach would-be attackers how to accomplish their mission.

What does the terror landscape look like on Sept. 11, 2020? There are some familiar faces as well as new threats keeping counter-extremism on its toes.

Al-Qaeda’s Latest Attack on the United States

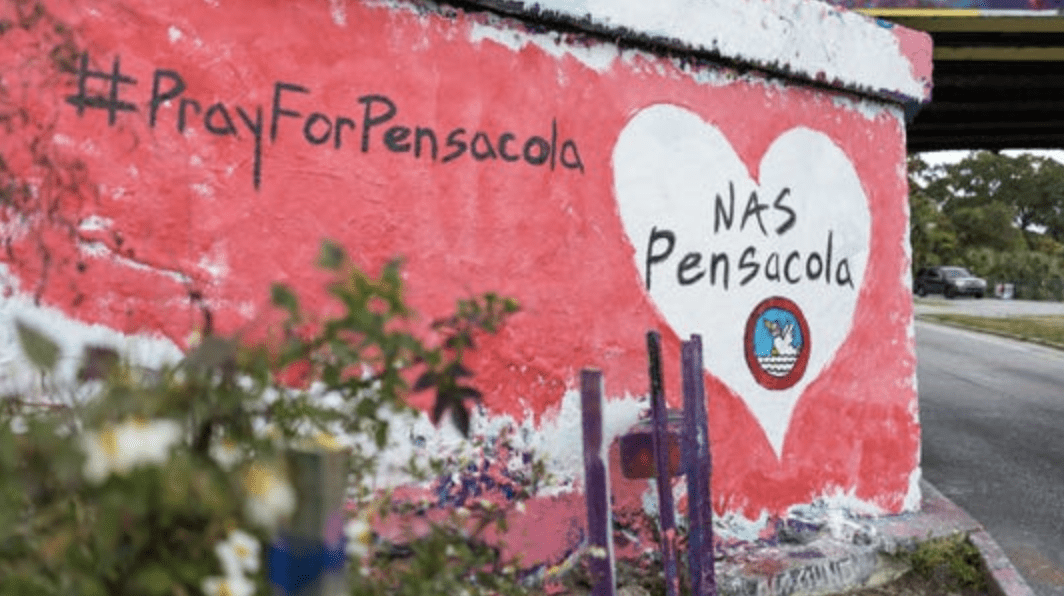

Between the 18th and 19th anniversaries of the 9/11 attacks, there was another al-Qaeda attack on America — the perpetrator even visited the 9/11 Memorial in New York City on Thanksgiving weekend before the Dec. 6, 2019, attack.

Second Lieutenant Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani, a member of the Royal Saudi Air Force, was training at Pensacola Naval Air Station when he entered a building on the base, killed three and wounded eight. Alshamrani was killed about eight minutes after he started shooting; he was armed with a semi-automatic handgun with an extended magazine, several ammunition magazines, and about 180 rounds of ammunition. He legally purchased the gun months earlier under an exception that allows nonimmigrant visa holders to purchase weapons if they have a valid state hunting license. He posted a message on Sept. 11 stating that the countdown had begun.

In February, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula leader Qasim al-Raymi said the terror group directed Alshamrani to conduct the attack. U.S. officials later confirmed that the shooter had communicated with al-Qaeda multiple times before the attack, in which he discussed carrying out a “special operation” for the group. FBI Director Christopher Wray said that Alshamrani’s communications and coordination confirmed he was “more than inspired” by AQAP.

Nathan Sales, the State Department’s coordinator for counterterrorism, said last year that al-Qaeda “has been strategic and patient over the past several years” and is “as strong as it has ever been.” Former DHS officials said in the new Future of DHS Project report from the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security that “the international terrorist threat from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and al-Qaeda has not gone away, and DHS needs to use the next two to three years to get ready for what is coming next.” AQAP’s Inspire magazine, still easily available online, remains a key reference for terrorists of all stripes because of its easy-to-follow instructions for attack preparation and execution.

The recruitment well is also deeper. While an al-Qaeda job application recovered from Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound included screening questions about the would-be jihadist’s history, health and hobbies, today the terror group welcomes connected operatives with access to critical infrastructure and key targets — IT experts, scientists, security guards, military, etc. — and at the same time understands they can still use lower-skill “open-source jihad” operatives to carry out simple attacks with less intense planning and fewer opportunities for authorities to intervene. “Jihad is with all, pious and immoral,” al-Raymi said in 2017, telling would-be jihadists to not stress so much about what they do and don’t have to bring to the table but to just “take it easy” and attack.

In line with the terror group’s focus on economic attacks, al-Qaeda recently declared the need to recruit and train for “e-jihad” — even taking advantage of Amazon’s broadband expansion project — in order to “ruthlessly” target infrastructure and financial systems like never before. Al-Qaeda even used the death of George Floyd and subsequent police-reform protests to try to recruit Christians as supporters.

The Taliban and Their Future Impact on Terror

It would have been hard to imagine that, 19 years after the most devastating attack on U.S. soil, America would be facilitating a deal with the al-Qaeda allies who gave safe haven to Osama bin Laden and hosted al-Qaeda training camps. It may have also been hard to imagine that this group that kept Afghanistan in the dark ages now embraces the internet to disseminate their propaganda articles, statements, videos, magazines, and Twitter feeds. In a video last year, the Taliban showed video of United Airlines Flight 175 striking the World Trade Center while stating that “this heavy slap on their dark faces was the consequence of their interventionist policies and not our doing.” Heading into Doha talks this week, President Trump told reporters that “we’re getting along very, very well with the Taliban.”

And that relationship with al-Qaeda seems as cozy as ever. Helmand province officials reported in July that al-Qaeda was training Taliban fighters, while a report from the United Nation’s Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team found that al-Qaeda and the Taliban had held a series of meetings on “cooperation related to operational planning, training and the provision by the Taliban of safe havens for al-Qaeda members inside Afghanistan,” with al-Qaeda covertly active in 12 provinces as “the Taliban appear to have strengthened their relationship with al-Qaeda rather than the opposite.”

Since inking a deal with the United States in a Doha ceremony on Feb. 29, the Taliban have touted the agreement “ending the occupation,” as the pact is described in their propaganda, as a victory for not just their jihadists but all who have fought in the name of Islam. A crucial currency in terrorist recruitment and retention is motivation – look past the grisly graphics, and you have a collection of breakroom-meme posters encouraging jihadists to bring their A-game and never give up. The struggle is real, they’re told, and for every step back (like major territorial losses) they’ll take two steps forward, even if it takes time and persistence. Taliban propaganda — which doesn’t attract the attention of online extremism censors like ISIS does — has long boasted that they would eventually bring “to their knees” American “crusaders,” and as their headlines scream that they essentially accomplished their goal it can serve as a shot in the arm to other terror groups operating with the same aims.

They’re also able to fuel terror narratives with the perceived lack of consequences for their actions, as the Taliban continued attacks during talks and didn’t lose their place at the negotiating table. Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Centre reported in February that the Taliban drove up the overall terror death toll in 2019 even as global terror attacks were on the decline. Taliban attacks increased by almost 90 percent with their fatalities up by more than 60 percent (more deaths than the next nine deadliest terror groups combined) as they surpassed ISIS to become the world’s deadliest non-state armed group. Yet, as they self-identified as a jihad-centered political entity, they traded a promise for U.S. withdrawal for a promise to behave. Terrorists no longer live, communicate, or recruit in silos: a victory against a common enemy is viewed at its core a victory for all, and that can feed the ever-growing and accessible ideological marketplace of terrorist ideas, methods and inspiration.

Rapid Growth of Domestic Extremism

Anti-Semitic and white supremacist terrorism is increasingly becoming a transnational threat that helps put the United States “at the doorstep of another 9/11,” but stopping the threat requires education and training for vulnerable communities and clear authorities to go after extremists and their online recruitment, DHS and FBI officials told Congress earlier this year. “Domestic terrorism by white supremacists and other ‘homegrown’ causes also needs more DHS attention and resources,” former DHS Assistant Secretary for Infrastructure Protection Caitlin Durkovich and former DHS Deputy Assistant Secretary for Counterterrorism Policy Thomas Warrick wrote in the Atlantic Council’s Future of DHS Project report, warning that “terrorist threats to the United States have changed from what they were immediately after 9/11 — and have further evolved from what they were as recently as 2016.”

Accelerationist movements, which can include white supremacists, neo-Nazis and other movements and seek to collapse society through violence and start anew, have been growing with increasingly global reach. We’ve recently seen accelerationists at play: Two professed members of the extremist Boogaloo Bois who claimed membership in a sub-group called the “Boojahideen” allegedly offered themselves as mercenaries to Hamas and delivered gun accessories to an undercover FBI employee they believed was a senior member of the terror group. The accused gunman in the slaying of a Federal Protective Service officer in Oakland in June is linked to the Boogaloo and was an active-duty staff sergeant stationed at Travis Air Force Base. Authorities said Steven Carrillo wrote “BOOG” and other phrases in his blood on the hood of a vehicle he later carjacked.

Propaganda and recruitment efforts are also up, as seen when a neo-Nazi group claiming their recent actions were spurred by “violent left-wing” protests posted flyers across the Arizona State University campus declaring “Hitler was right,” among other anti-Semitic messages. In a February update tracking of white supremacist propaganda, the ADL said there were 2,713 cases of racist, anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ fliers, stickers, banners and posters distributed or posted on or off campuses in 2019 — double the number of incidents in 2018 and the highest level of activity recorded by the organization. About a fourth of incidents in 2019 occurred on college campuses; this trend has risen since white supremacist groups increased their targeting of campuses with recruitment flyers beginning in 2016.

Islamist extremist propaganda and white supremacist propaganda reflect similar themes and memes in the ways they recruit and incite, contributing to the internet’s ample open-source library of D.I.Y. extremist training and incitement – from posters to videos, from social media to magazines – that bridges group allegiances and ideologies. At times they mimic each other’s memes, promote ideological dominion, urge copycats to emulate infamous attacks, threaten the social media companies that try to rein in their propaganda, praise and promote attacks that have recently occurred, circulate machismo-saturated training camp videos, and heavily traffic in anti-Semitism.

One key shared characteristic of recruitment is how Islamist extremists and white supremacists both try to appeal to grievances, hoping that potential recruits who might not otherwise join their movements could be pushed over the edge with targeted psychological messaging. Similarly, both groups seize on current events to promote core anti-government and retribution themes, trying to appeal to would-be recruits as if they’re soldiers in a cultural or kinetic war – as one recruitment propaganda poster from the neo-Nazi Feuerkrieg Division put it, “Turn your sadness into rage.” Islamist extremists and white supremacists hope to seize on the energy of current events whether it’s white supremacists using debates over Confederate monuments or Islamist terror groups using Western military operations – and both ideological movements trying to use the coronavirus pandemic to their advantage – to steer some of that fury into their movements to stoke anger and gain new recruits.

How ISIS Lives on

In terms of propaganda, ISIS has tried to make the best — they “had to tactically retreat from some areas” and defeats were only only “a temporary transition,” claimed one article — out of a caliphate-less situation. And that’s been made easier by design: as much as they boasted about having an Islamic State straddling Syria and Iraq, ISIS was molded to be a virtual organization at its core that could recruit, inspire, and instruct through an internet connection. Eliminating recruiter boots on the ground in every neighborhood and the need to travel to far-flung training camps served as a force multiplier for their movement and drew a broad swath of homegrown recruits beyond perhaps even Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s expectations.

The Defense Intelligence Agency and U.S. Central Command told the Defense Department’s inspector general months ago that “following the death of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the group’s capabilities in Syria remained the same… ISIS remained cohesive, with an intact command and control structure, urban clandestine networks” and operating as an insurgency. In the online sphere, the terror group has an army of keyboard jihadists supporting official ISIS media operations, creating and disseminating everything from posters encouraging attack tactics or targets to video and English-language magazines. A “lockdown special” edition of The Voice of Hind magazine published by ISIS supporters in India encouraged steps to “annihilate the disbelievers” including stabbing people with scissors and expending “less effort” by spreading COVID-19. A new 24-page cybersecurity magazine for ISIS supporters walks jihadists through step-by-step security for smartphones — while encouraging them to use a computer instead for more secure terror-related business — and warns of “nightmare” Windows collecting user data from geolocation to browsing history. And a recent video from the Islamic State’s media wing tells followers that arson is the highest-rated of the low-skill terror tactics and encourages fire attacks with the devastation and death toll of the 2018 Camp Fire in California highlighted as an example.

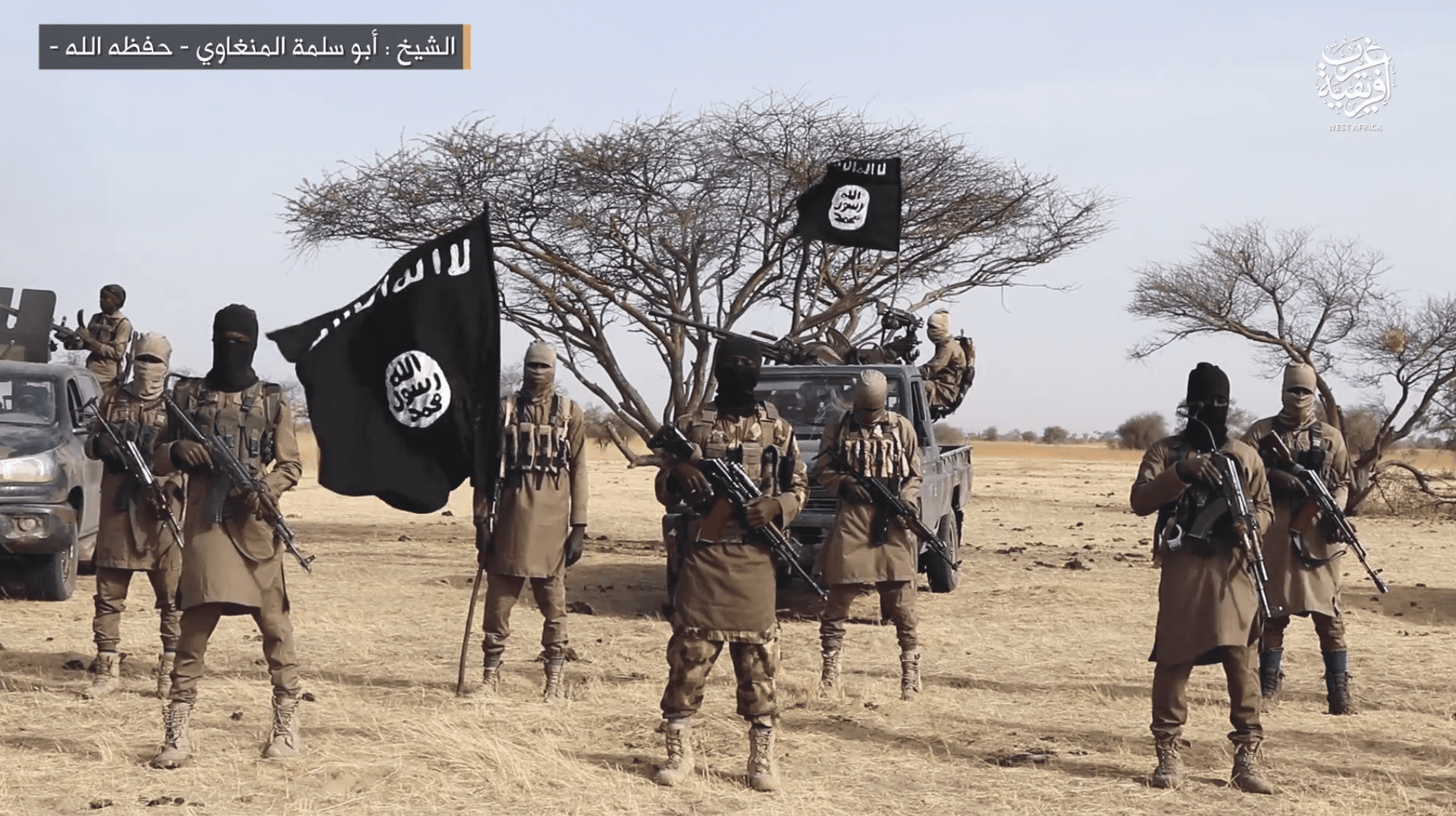

ISIS has not been defeated but has evolved out of necessity and in line with its original goal of becoming a global, insidious terror outfit. ISIS provinces are still active, particularly through attacks in West Africa and Afghanistan. But they’ve laid down a framework of borderless jihad and a blueprint for growing a terror movement both on the dark web and the open internet that is impossible to rein in.

The Next Front in Africa

In January, al-Qaeda exhorted adherents to follow the “brilliant” example of Al-Shabaab terrorists who killed three Americans in a raid on a Kenyan base. The surprise attack by a team of militants, which AFRICOM said breached the perimeter and involved mortar and small-arms fire, resulted in an hourlong gunbattle; several airplanes, fuel tankers and vehicles were destroyed or damaged. U.S. Army Specialist Heny Mayfield Jr., 23, of Hazel Crest, Ill., was killed in the pre-dawn attack on the Manda Bay Airfield on Jan. 5, along with L3Harris Technologies contractor pilots Dustin Harrison, 47, and Bruce Triplett, 64. A third contractor was wounded. Al-Shabaab is “a dangerous enemy that presents a threat to Somalia, its neighbors, and the United States,” AFRICOM said last month.

In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, deaths resulting from terrorist attacks leaped fivefold from 2016 to 2019. Terror thrives and grows where the world neglects to pay proper attention to extremists taking advantage of weaker security situations to set up shop. “ISIS and Al Qaeda are on the march in West Africa. They’re having success and the international efforts are not,” U.S. Africa Command leader Gen. Stephen Townsend told the House Armed Services Committee in March.

A common enemy can also sometimes make bedfellows out of entities we might not predict — like the ISIS and al-Qaeda alliance in West Africa. “Al-Qaeda and ISIS cooperate with one another; I can’t really explain that,” Townsend said, musing that it might be because some of these terrorists grew up together. He noted that “if ISIS can carve out a new caliphate or al-Qaeda can, they will do it and they will attempt to do it in West Africa.” If the threat continues to grow at its current pace – a fivefold increase in terror activity since last year in the Sahel alone – he said, “unchecked, this threat becomes a threat beyond the region.”

When Conspiracy Theory Extremism Turns Violent

The 9/11 attacks bred their own conspiracy theory: the 9/11 “truthers,” who allege that the attacks were an “inside job.” Nineteen years after al-Qaeda struck, extremism generated by conspiracy theories constitutes its own threat. In December 2016, Edgar Maddison Welch drove to the Forest Hills neighborhood of Washington and entered Comet Ping Pong, a family pizza shop and venue for local bands, with a .38 caliber handgun and an AR-15, firing rounds from the rifle before surrendering to police. He claimed he was investigating the “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory that alleged Democratic Party officials ran a child sex ring out of various restaurants, and the gunman vowed to rescue non-existent captive children from the restaurant’s non-existent basement. In December, Ryan Jaselskis of California pleaded guilty to setting a fire inside of Comet Ping Pong — again, luckily no one was injured. A Pizzagate video was posted on his parents’ YouTube account an hour before the arson. And this spring, threats against the pizza parlor and its employees ramped up again, with the owner speculating that “it’s part of a disruptive movement,” a “purposely designed, something-backed movement.”

Threats posed by COVID-19 were detailed in an April Joint Intelligence Bulletin from DHS, the FBI, and National Counterterrorism Center warning law enforcement that domestic extremists were “extremely likely” to continue attacks linked to the pandemic. White supremacist Timothy Wilson, killed in March in an FBI shootout as his alleged plan to bomb a Missouri hospital was disrupted, linked the plot to the pandemic, stating that “if he contracts COVID-19, he would conduct a ‘lone wolf attack’ and ‘try to take out as many as I can during that time, but I don’t want to sit in a hospital bed and die, doing nothing.’” Wilson wanted to “attack high value targets if the government issued martial law and quarantine orders as a result of COVID-19.” At the end of March, Edward Moreno, a train engineer who shared conspiracy theories about nefarious pandemic “segregating” intent of the Navy’s hospital ship in the Port of Los Angeles derailed the train with the intent of striking the USNS Mercy, according to prosecutors

Conspiracy theories around coronavirus have led to other criminal acts. Dozens of communications towers in the UK have been targeted by arsonists and telecom employees harassed as a result of a conspiracy theory alleging that 5G technology is connected to the spread of the coronavirus. The latest 5g/COVID conspiracy theory alleges that the nose bridge of surgical masks contains 5G antennas that are being used to track people. A recent DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency memo to industry partners warned that “while the U.S. has not seen similar levels of attacks against 5G infrastructure linked to the pandemic, the tactics used in Western Europe [have] begun to migrate to the U.S.”

Believers of QAnon, described by extremism researchers at the Anti-Defamation League as “first and foremost an online trolling and disinformation movement” that began in 2017 on the 4chan message board, have been involved in incidents including threats and attacks. Forrest Clark, accused of setting a destructive wildfire in Orange County, Calif., in 2018, posted QAnon links on his Facebook page. Jeffrey Gardner Boyd, arrested in Pennsylvania in 2018 and charged with threatening to kill the president and his family, “had become convinced that a Pennsylvania woman who posts about QAnon on Twitter was being held hostage by shadowy forces” and thought Trump was under CIA mind control. Anthony Comello, the suspect in last year’s shooting of alleged Gambino family boss Francesco “Frank” Cali, believes in QAnon and thought Cali “was a prominent member of the deep state, and, accordingly, an appropriate target for a citizen’s arrest,” Comello’s attorney wrote in court documents. Jessica Prim of Illinois, who shared QAnon theories online, was arrested in New York this spring with a stash of knives after posting on her Facebook page, “Hillary Clinton and her assistant, Joe Biden and Tony Podesta need to be taken out in the name of Babylon! I can’t be set free without them gone. Wake me up!!!!!” Matthew Wright pleaded guilty to blocking a bridge at the Hoover Dam in 2018 with an armored truck, holding up a sign referring to a prominent QAnon demand; behind bars, he would sign a letter with the common QAnon phrase “where we go one, we go all.”

A May 2019 intelligence bulletin from the FBI’s Phoenix Field Office warned that “anti-government, identity based, and fringe political conspiracy theories very likely motivate some domestic extremists,” and some theories “very likely encourage the targeting of specific people places and organizations” while some narratives “tacitly support or legitimize violent action.” The FBI “assumes some, but not all individuals or domestic extremists who hold such beliefs will act on them” but notes that the spread of conspiracy theories in the “modern information marketplace” could be mitigated by social media companies regulating potentially harmful content.

“Promoters of conspiracy theories, claiming to act as ‘researchers’ or ‘investigators,’ single out people, businesses, or groups which they falsely accuse of being involved in the imagined scheme,” the bulletin continues. “These targets are then subjected to harassment campaigns and threats by supporters of the theory, and become vulnerable to violence or other dangerous acts.”

(Visited 2,271 times, 5 visits today)