Looking for Life on a Flat Earth

On the last Sunday afternoon in March, Mike Hughes, a sixty-two-year-old limousine driver from Apple Valley, California, successfully launched himself above the Mojave Desert in a homemade steam-powered rocket. He’d been trying for years, in one way or another. In 2002, Hughes set a Guinness World Record for the longest ramp jump—a hundred and three feet—in a limo, a stretch Lincoln Town Car. In 2014, he allegedly flew thirteen hundred and seventy-four feet in a garage-built rocket and was injured when it crashed. He planned to try again in 2016, but his Kickstarter campaign, which aimed to raise a hundred and fifty thousand dollars, netted just two supporters and three hundred and ten dollars. Further attempts were scrubbed—mechanical problems, logistical hurdles, hassles from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Finally, a couple of months ago, he made good. Stuff was leaking, bolts needed tightening, but at around three o’clock, and with no countdown, Hughes blasted off from a portable ramp—attached to a motorhome he’d bought through Craigslist—soared to nearly nineteen hundred feet, and, after a minute or so, parachuted less than gently back to Earth.

For all of that, Hughes might have attracted little media attention were it not for his outspoken belief that the world is flat. “Do I believe the Earth is shaped like a Frisbee? I believe it is,” he told the Associated Press. “Do I know for sure? No. That’s why I want to go up in space.”

Hughes converted fairly recently. In 2017, he called in to the Infinite Plane Society, a live-stream YouTube channel that discusses Earth’s flatness and other matters, to announce his beliefs and ambitions and ask for the community’s endorsement. Soon afterward, The Daily Plane, a flat-Earth information site (“News, Media and Science in a post-Globe Reality”), sponsored a GoFundMe campaign that raised more than seventy-five hundred dollars on Hughes’s behalf, enabling him to make the Mojave jump with the words “Research Flat Earth” emblazoned on his rocket.

To be clear, Hughes did not expect his flight to demonstrate Earth’s flatness to him; nineteen hundred feet up, or even a mile, is too low of a vantage point. And he doesn’t like that the mainstream media has portrayed things otherwise. This flight was just practice. His flat-Earth mission will come sometime in the future, when he will launch a rocket from a balloon (a “rockoon”) and go perhaps seventy miles up, where the splendor of our disk will be evident beyond dispute.

If you are only just waking up to the twenty-first century, you should know that, according to a growing number of people, much of what you’ve been taught about our planet is a lie: Earth really is flat. We know this because dozens, if not hundreds, of YouTube videos describe the coverup. We’ve listened to podcasts—Flat Earth Conspiracy, The Flat Earth Podcast—that parse the minutiae of various flat-Earth models, and the very wonkiness of the discussion indicates that the over-all theory is as sound and valid as any other scientific theory. We know because on a clear, cool day it is sometimes possible, from southwestern Michigan, to see the Chicago skyline, more than fifty miles away—an impossibility were Earth actually curved. We know because, last February, Kyrie Irving, the Boston Celtics point guard, told us so. “The Earth is flat,” he said. “It’s right in front of our faces. I’m telling you, it’s right in front of our faces. They lie to us.” We know because, last November, a year and a day after Donald Trump was elected President, more than five hundred people from across this flat Earth paid as much as two hundred and forty-nine dollars each to attend the first-ever Flat Earth Conference, in a suburb of Raleigh, North Carolina.

“Look around you,” Darryle Marble, the first featured speaker on the first morning of the conference, told the audience. “You’ll notice there’s not a single tinfoil hat.” He added, “We are normal people that have an abnormal perspective.”

The unsettling thing about spending two days at a convention of people who believe that Earth is flat isn’t the possibility that you, too, might come to accept their world view, although I did worry a little about that. Rather, it’s the very real likelihood that, after sitting through hours of presentations on “scientism,” lightning angels, and NASA’s many conspiracies—the moon-landing hoax, the International Fake Station, so-called satellites—and in chatting with I.T. specialists, cops, college students, and fashionably dressed families with young children, all of them unfailingly earnest and lovely, you will come to actually understand why a growing number of people are dead certain that Earth is flat. Because that truth is unnerving.

The November conference was held in a darkened ballroom of an Embassy Suites near the Raleigh airport. Dozens of rows of chairs had been set out and nearly all were filled. To my right, a young couple with a stroller listened intently; a man in front of me wore a T-shirt with the words “They Lied” across the back. Onstage, Marble recounted his awakening. Marble is African-American and was one of a handful of people of color in the room. He had enlisted in the Army and gone to Iraq after 9/11; when he returned home, to Arkansas, he “got into this whole conspiracy situation,” he said.

For two years, Marble and his girlfriend drank in YouTube. “We went from one thing to another to another—Sandy Hook, 9/11, false flags,” he said. “We got into the Bilderberg, Rothschilds, Illuminati. All these general things that one ends up looking into when you go on here, because you look at one video and then another suggestion pops up along the same lines.” Finally, he had to step away. “You come to a place where you start to feel that reality is just kind of scary,” he said. “You’ll find out that nothing, ultimately, is what it seems to be. I hit my low point, where everything was just terrifying.”

Marble found the light in his YouTube sidebar. While looking for videos related to “Under the Dome,” a TV sci-fi drama, he came across “Under the Dome,” a two-hour film, which takes the form of a documentary, by Mark K. Sargent, one of the leading flat-Earth proselytizers. The flat-Earth movement had burbled along in relative darkness until February of 2015, when Sargent uploaded “Flat Earth Clues,” a series of well-produced videos that, the Enclosed World site notes, “delves into the possibility of our human civilization actually being inside a ‘Truman Show’-like enclosed system, and how it’s been hidden from the public.” (Access to those videos and more is available on Sargent’s personal Web site, for ten dollars a month.) It announced itself as “a Reader’s Digest version” of the flat-Earth theory; Marble watched it over and over, all weekend.

“Each thing started to make that much more sense,” he said. “I was already primed to receive the whole flat-Earth idea, because we had already come to the conclusion that we were being deceived about so many other things. So of course they would lie to us about this.”

If we can agree on anything anymore, it’s that we live in a post-truth era. Facts are no longer correct or incorrect; everything is potentially true unless it’s disagreeable, in which case it’s fake. Recently, Lesley Stahl, of “60 Minutes,” revealed that, in an interview after the 2016 election, Donald Trump told her that the reason he maligns the press is “to discredit you all and demean you all so that when you write negative stories about me no one will believe you.” Or, as George Costanza put it, coming from the opposite direction, “It’s not a lie if you believe it.”

The flat Earth is the post-truth landscape. As a group, its residents view themselves as staunch empiricists, their eyes wide open. The plane truth, they say, can be grasped in experiments that anyone can do at home. For instance, approach a large body of water and hold up a ruler to the horizon: it’s flat all the way across. What pond, lake, or sea have you ever seen where the surface of its waters curves? Another argument holds that, if Earth were truly spherical, an airplane flying above it would need to constantly adjust its nose downward to avoid flying straight into space. If, say, you flew on a plane and put a spirit level—one of those levels that you buy at the hardware store, with a capsule of liquid and an air bubble in the middle—on your tray table, the level should reveal a slight downward inclination. But it doesn’t: the level is level, the flight is level, the nose of the plane is level, and therefore the surface of Earth must be level. Marble performed this experiment himself, recorded it, posted it on YouTube, and a co-worker started a Reddit thread that linked to it. Soon Marble had twenty-two thousand followers and a nickname, the Spirit-Level Guy.

“We’re not trying to express any degree of intellectual superiority,” he said at the conference. “I’m just trying to wake people up to the idea that they’ve been lied to. It’s what you would do with any friend.”

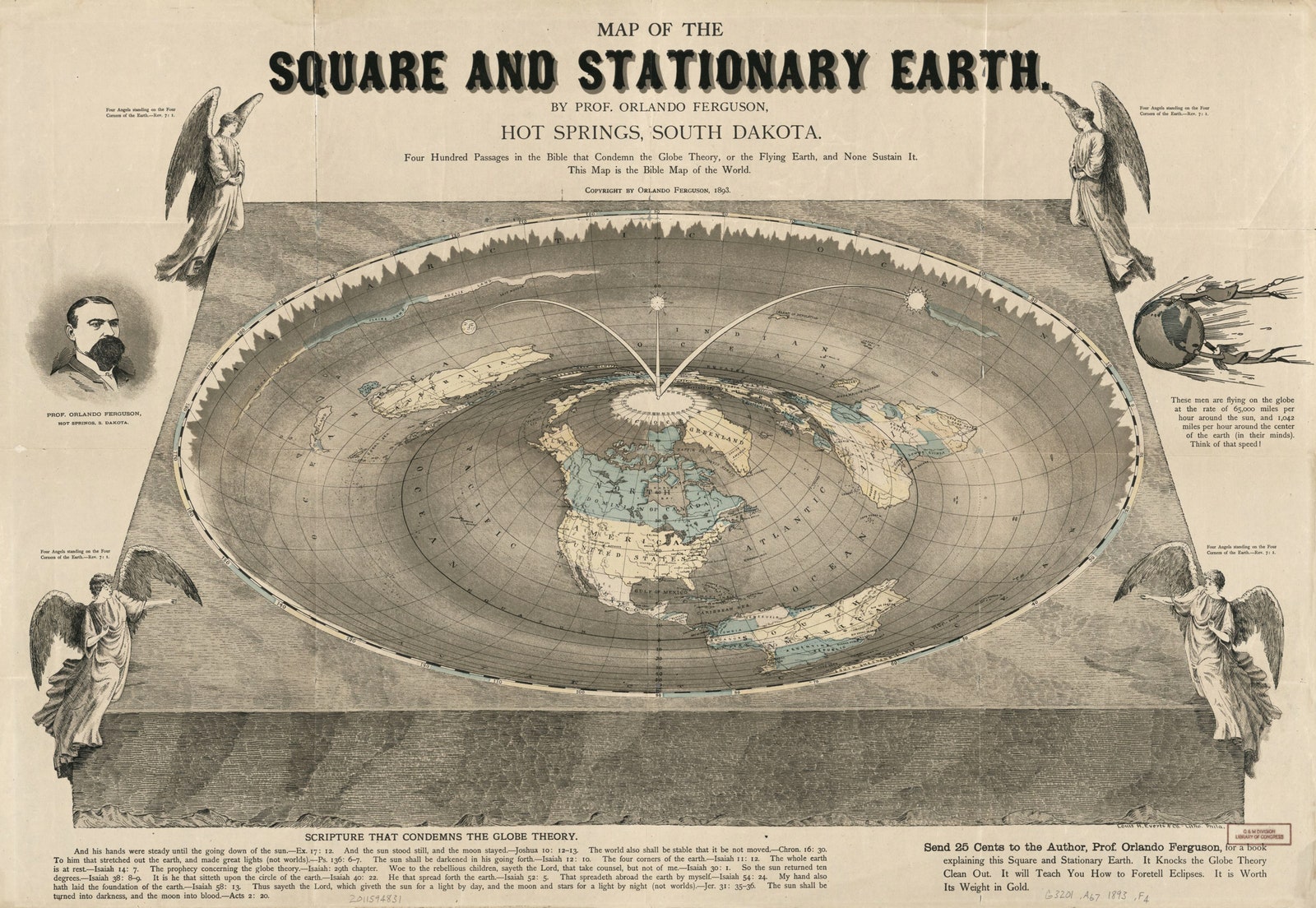

The modern case for a flat Earth derives largely from “Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe,” a book published, in 1865, by a smooth-talking English inventor and religious fundamentalist named Samuel Rowbotham. I found a copy at a bookseller’s table in the corridor just outside the conference ballroom, alongside books about the Revelations and New Testament apocrypha. The vender, a friendly woman who looked to be in her late sixties, offered her thoughts on Earth’s flatness and the enshrouding secrecy; I moved on when she got to “the Jews.”

Rowbotham began espousing his theory in the eighteen-forties, writing and lecturing under the pseudonym Parallax. He envisaged a disk, with the North Pole at the center and Antarctica a wall of ice around the perimeter. The sun, moon, and stars? All less than a thousand miles away and “much smaller than the earth from which they are measured.” Rowbotham proceeded by way of “zetetic” reasoning (from the Greek zeteo, meaning “to seek or inquire,” he explained), arguing that the facts show that Earth is flat whereas the theory of its roundness is unproven. He had demonstrated this himself at a drainage canal in the east of England. The canal runs arrow-straight for six miles, and Rowbotham, standing at one end, claimed to be able to see a boat at the other. (The planet’s curvature drops eight inches for every mile of distance squared, so an object six miles away ought to have been twenty-four feet below the sight line.)

Rowbotham’s ideas gained traction, and when he died, in 1884, his followers formed the Universal Zetetic Society. It published a magazine, The Earth Not a Globe Review, that decried the teaching of astronomy to schoolchildren, ridiculed evolution, and entertained alternative theories, including the possibility that Earth is a cube. And it developed a base in the United States; until the nineteen-forties, the town of Zion, north of Chicago, followed a strict religious code that embraced a flat-Earth doctrine. The Universal Zetetic Society sputtered out but was revived under different names over the years—in 1956, 1972, and 2004. The core model remained largely unchanged from Rowbotham’s day, although it was updated to account for space travel and other mid-twentieth-century fictions.

I encountered Robbie Davidson, the organizer of the conference, in a corridor outside the ballroom. Davidson is the director and sole employee of Kryptoz Media, a company based in Edmonton, Canada. He is tall and sharp-featured, and when he speaks his sentences spill into one another. He told me that he was turned on to the flat-Earth scene in 2015; before that, Kryptoz was marketing cryptocurrencies to everyday consumers. He described the modern flat-Earth community as a confluence of three strains of thought. “There’s the conspiratorial,” he said. “It’s like, ‘That’s kind of weird with the moon landing. Maybe I’ll look into it. What else could they be lying about?’ ” The second is “the scientific-minded,” people who “just want to go out and do the experiments.” The third, Davidson said, “is the spiritual—people that want to say, ‘Wait a minute, what would happen if I took the Bible literally?’ ” In style and substance, the flat-Earth movement is a close cousin of creationism. At the end of the conference, Davidson would be screening his new documentary, “Scientism Exposed 2,” which dismisses dinosaurs, evolution, gravitational waves, and a spherical Earth as part of a broad agenda “to hide the true creator of Creation,” according to the trailer.

Davidson was pleased with the turnout in Raleigh and was already planning for the 2018 conference, in Denver; another, in Canada, will be held this August. “More people are waking up,” he said. Davidson was careful to note that the conferences are unaffiliated with the Flat Earth Society, which, he said, promotes a model in which Earth is not a stationary plane, with the sun, moon, and stars inside a dome, but a disk flying through space. “They make it look incredibly ridiculous,” he told me recently. “A flying pancake in space is preposterous.”

Here are some reasons why you may think that Earth is actually a rotating sphere. For one, some of the ancient Greeks said so: if the moon is round, Earth must be, too (Pythagoras); as you move north or south from the equator, you see a changing array of stars and constellations (Aristotle); you can calculate Earth’s circumference by comparing the lengths of the shadows of two tall sticks placed many miles apart (Eratosthenes). More recently, we’ve noticed that solar noon—the point in the day when the sun is highest—doesn’t happen everywhere on Earth at the same time. (Time zones were invented to address this dilemma). Also, the higher you climb in elevation, the farther into the horizon you can see; if Earth were flat, you’d see an equal distance—to the edge of the world, with a strong enough telescope and an unobstructed view—regardless of altitude.

Human engineering seemingly takes Earth’s curvature into account. Lighthouses are deliberately built tall so that their beams can be seen from ships far away, over the intervening curve of sea. Radio towers send their signals dozens or hundreds of miles by bouncing them off the ionosphere, which wouldn’t be necessary if Earth were flat. A long bridge appears flat because its span parallels Earth, but its supports betray the curvature; the towers of the Verrazano-Narrows, in New York, are more than an inch and a half farther apart at the top than at the bases. And, of course, we have photographic evidence of a globular planet—millions of examples since the nineteen-fifties, taken by spacecraft and orbiting satellites.

Flat-Earthers have lists of reasons why round-Earthers—globers, globetards—are wrong. Perhaps the most comprehensive is “200 Proofs that Earth is Not a Spinning Ball,” a video posted to YouTube by Eric Dubay, a yoga instructor who regards himself as the true modern reviver of flat-Earth philosophy. (Dubay has also gained attention for his Holocaust denialism.) Many of the proofs fall into the you-can’t-definitively-prove-that-I’m-wrong category. If Earth is spinning on its axis at a thousand miles per hour, as scientists say, why isn’t there a powerful wind blowing exclusively from one direction? (Dubay: “The proof that the Earth is at rest is proved by kite flying.”) If Earth is a ball, why are there no direct flights across Antarctica from Chile to New Zealand? (“These flights aren’t made because they’re impossible.”)

Of course, such arguments prompt further questions. If Earth is actually flat, why does the sun rise and set? Where does it go at night? If it’s true that the sun and the moon never actually dip below the horizon but instead travel in wide circles around the North Pole, what keeps them aloft? And what about all those satellites I’ve seen being launched into space?

The responses recede along a path from half-baked to evasive. The sun is barely three dozen miles wide (see Thomas Winship’s “Zetetic Cosmogony,” from 1899), so of course its rays don’t illuminate the whole of Earth at once; as it moves farther from you it appears closer to the horizon, just as the farthest in a series of streetlights appears closest to the ground. And those televised rocket launches? They’re fake. (Notice how the camera angle quickly shifts from a ground-up shot to one supposedly on the rocket itself, looking back toward Earth. And all of those alleged images of a round Earth were Photoshopped.) Yes, you’ve been told, or you’ve read, that Antarctica sees weeks of twenty-four-hour daylight—but have you ever been there and seen it for yourself? Gravity, too, is just another theory; flat-Earthers believe that objects simply fall. (“ ‘Gravity,’ they love that one,” Marble said, using air quotes. “Grabbity—with two ‘B’s.”)