America’s flat-Earth movement appears to be growing

IT IS a stunt worthy of Evel Knievel. This week, if all goes to plan, “Mad” Mike Hughes, a Californian, will launch himself 1,800 feet (550 metres) into the sky in a homemade steam-powered rocket made of scrap metal. As well as providing entertainment, Mr Hughes wants to prove a point. On his trip over the Mojave Desert, which could propel him at speeds of up to 500 miles (800km) per hour, the 61-year-old limousine-driver-turned-daredevil hopes to prove that the Earth is flat.

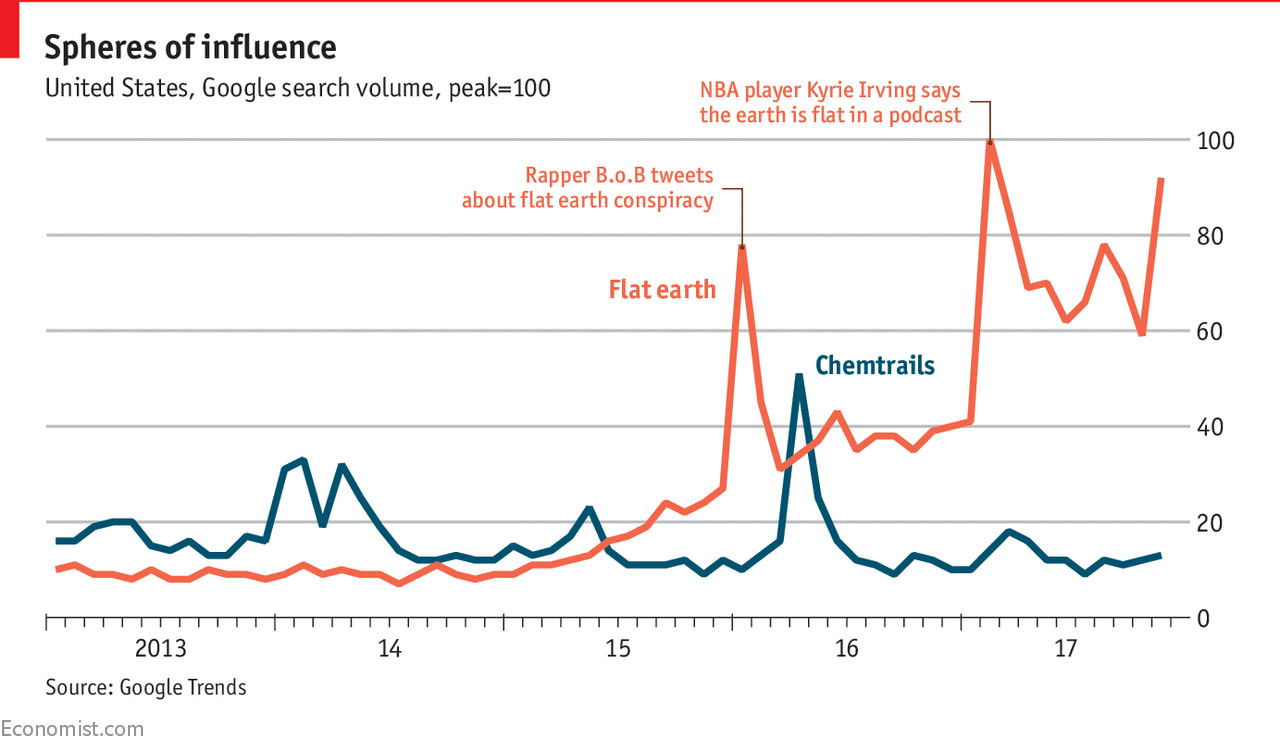

Some may be surprised to learn that people still hold such views. After all, the Earth has been photographed from space. But such photos could have been faked by the evil forces who secretly control the world, right? And all those centuries of scientific evidence suggesting that the Earth is spherical could be wrong, right? In America interest in the flat-Earth movement appears to be growing. In September Bobby Ray Simmons Jr., a rapper also known as B.o.B, launched a crowd-funding campaign to send satellites into orbit to determine the Earth’s shape. On November 9th, 500 “flat-Earthers” assembled in North Carolina for the first annual Flat Earth International Conference. Data from Google Trends show that in the past two years, searches for “flat earth” have more than tripled (see chart).

Conspiracy theories are not always harmless. The bogus notion that vaccines cause autism has led to a decline in immunisation rates in some places, which has allowed outbreaks of measles. Scepticism about climate change has infiltrated schools. A recent survey found that a third of American science teachers tell their students that climate change is driven in part by natural causes. One in ten say humans play no role in it.

Conspiracy theories are appealing because they offer simple explanations for complex phenomena, or because they let people believe they are in possession of secret knowledge that the powerful wish to suppress. They tend to be most popular among less-educated people who do not trust public institutions. They are extremely common in dictatorships, where people assume, often correctly, that the authorities are lying.

Simply rebutting conspiracy theories may make adherents even more entrenched in their views. (If “they” are so keen to deny it, it must be true!) Absence of evidence is taken as evidence of a fiendishly effective cover-up. Some conspiracy theories are irrefutable—the American government cannot prove, for example, that it is not storing dead aliens in a secret underground laboratory.

If schools were better at teaching analytical thinking, that might reduce the appeal of conspiracy theories. And it would not hurt if governments were more open and trustworthy. Meanwhile, the best response is often to ignore the tinfoil-hat brigade. After the rapper B.o.B sparked an argument on Twitter about the shape of the Earth in 2016, one of the groups supposedly responsible for misleading the public on this point, NASA, chose not to weigh in. A spokeswoman told the Washington Post: “we don’t think there’s a debate to be had.”

*** This article has been archived for your research. The original version from The Economist can be found here ***