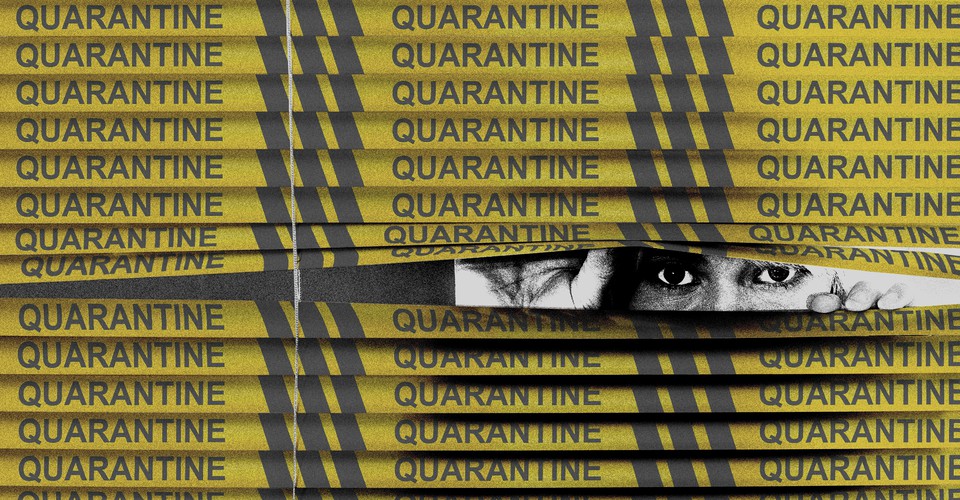

The Coronavirus Conspiracy Boom

COVID-19 has created a perfect storm for conspiracy theorists. Here we have a global pandemic, a crashing economy, social isolation, and restrictive government policies: All of these can cause feelings of extreme anxiety, powerlessness, and stress, which in turn encourage conspiracy beliefs. For more than a month, an urban legend that the pandemic was predicted in an early-’80s Dean Koontz thriller has been circulating on social media. Meanwhile, QAnon believers are circulating the “mole children” theory, which holds that the virus is a ploy to arrest members of the satanic “deep state” (Tom Hanks, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton) and to release their hostages (sex-slave children) from underneath Central Park. (Tom Hanks’s appearance on Saturday Night Live should have quelled speculation that he had been arrested for child molestation, but—in typical conspiratorial fashion—believers simply explained the irregularity away, claiming that Hanks’s monologue was a deepfake.)

But if the coronavirus pandemic is fertile ground for conspiracism, it’s also an opportunity—a rare chance for social scientists to examine just how many Americans will adopt conspiracy theories given the right set of circumstances. While laboratory experiments and public-opinion surveys are useful for understanding the basic structure of conspiracy beliefs, they can’t simulate real-world catastrophes of the kind that make conspiracy theories appealing to some people. It’s wise to step back and use these unique circumstances to consider what conspiracy theories can tell us about the media, the government, and ourselves. It turns out they can tell us a lot.

Read: What you need to know about the coronavirus

Mainstream coronavirus conspiracy theories come in two varieties: those that doubt the virus’s severity and those that suggest it might be a bioweapon. The former was endorsed by President Trump, who, early in the pandemic, referred to the virus as the Democrats’ “new hoax.” Even though he has taken the virus more seriously since mid-March, he has yet to explicitly condemn the idea that the threat of the virus has been exaggerated, or to encourage like-minded partisans in government and media to take it seriously. Indeed, conservative-media personalities continue to cast doubt on the reality of the pandemic, even as the death toll rises. Rush Limbaugh, for instance, suggested that our public-health officials are deep-state operatives and might not even be health experts. Some conservative commentators have pushed the theory that our hospitals aren’t actually treating any COVID-19 patients, going so far as to encourage people to stake out local hospitals and film the number of patients going in and out.

The second type of coronavirus conspiracy theory claims that the virus was intentionally disseminated by foreign powers, such as China or Russia, or by billionaire philanthropists such as George Soros and Bill Gates: Maybe China created or was working with this strain of coronavirus in a laboratory, and that the virus escaped by accident, or maybe Gates and the World Health Organization are at work on some nefarious plot to “control, and rule the world” with vaccines. A particularly disruptive version of this conspiracy theory connects the virus to 5G technology; it has driven believers to damage cell towers across Europe in recent weeks.

To see how much traction these two central variants of coronavirus conspiracy theories were receiving in the earlier stages of the pandemic, we polled a representative sample of 2,023 Americans from March 17 to 19 about their beliefs in these and many other conspiracy theories. We also asked survey respondents about their party affiliation and ideological leanings, as well as questions designed to capture relevant worldviews.

Read: An unprecedented divide between red and blue America

Because the pandemic, and reactions from federal and state governments, continues to evolve, we must note that our results are but a single snapshot of what we expect to be a lengthy timeline. That said, conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 were likely more influential at the outset of the pandemic, when our survey was conducted, and when social distancing, hand-washing, and other preventive measures—the types of behaviors discouraged by conspiracy beliefs—had the greatest potential to mitigate the spread of the virus. For that reason, our results are instructive for understanding the maximum impact of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs.

Almost everyone told us that they believe in one of the 22 conspiracy theories we asked about. In fact, only 9 percent of respondents didn’t express some level of agreement with any of the 22. Fifty-four percent believe that the “1 percent” of the wealthiest Americans secretly control the government; 50 percent believe that billionaire Jeffrey Epstein was murdered to conceal his activities; 45 percent believe that the dangers of genetically modified foods are being hidden from the public; and 43 percent believe that an extrajudicial deep state is secretly embedded in our government. Partisan conspiracy theories—those that explicitly accuse members of one party of conspiring—also have strong support. Thirty-seven percent of Americans believe that Trump colluded with Russia to steal the 2016 election and that Trump is a Russian asset. Twenty-eight percent believe that Hillary Clinton provided Russia with nuclear materials, and 20 percent still believe that Barack Obama faked his citizenship to illegally usurp the presidency.

Meanwhile, 29 percent believe that the threat of the virus was being exaggerated to hurt President Trump’s chances at reelection, and 31 percent believe that the virus was created and spread on purpose. In other words, belief in coronavirus conspiracy theories is about in the middle: about 20 percentage points lower than beliefs in the Epstein and the “1 percent” theories, but about twice as high as beliefs in theories that school shootings are “false flag” events, and that the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust has been exaggerated. Other health conspiracy theories exhibit similar levels of support among the mass public: 30 percent believe that the dangers of vaccines have been concealed, and 26 percent believe as much about 5G technology.

Read: What the ‘liberate’ protests really mean for Republicans

These are troublesome numbers, but our optimistic view—given what we know about other conspiracy beliefs—is that the numbers could be much higher. Of course, more polling is needed to track the life cycle of these theories as the pandemic unfolds. But, given the unprecedented levels of stress, uncertainty, and feelings of powerlessness Americans are coping with, the numbers are likely indicative of a natural ceiling in conspiracy beliefs that will be hard to break without greater numbers of influential figures peddling them.

Where do these beliefs come from?

A common misconception is that the internet, and social media in particular, is responsible for the seeming proliferation of conspiracy theories in American political culture. But while these platforms make spreading any idea easier and more efficient, the internet is but a tool for disseminating a human concoction. For the most part, social scientists have yet to find evidence that conspiracy beliefs have increased in the internet age. Indeed, some conspiracy theories, such as those surrounding the Kennedy assassination, lost support as internet access and use spread. Instead, conspiracy beliefs have roots in fundamental elements of human psychology and interaction.

The first of those elements is group attachments. Simply put, people are prone to believing that their group is good and right, and that other, competing groups are dangerous, malicious, or otherwise wrong. For example, people tend to view politics through their own partisan or ideological lens: Their party, its members, and its priorities are correct, and the other party is incompetent or corrupt. This dynamic explains why some Republicans believe that Obama “faked” his birth certificate or that Clinton secretly dealt uranium to the Russians, just as it accounts for some Democrats’ beliefs that Trump is a Russian asset.

Read: No, the internet is not good again

These group attachments don’t operate solely from the bottom up. They can be activated by “cues”—speeches, advertisements, tweets—from their group’s leaders. If public officials or media personalities associated with a political party spread conspiracy theories, their followers are more likely to take that information to heart and adopt those beliefs. Take the theory that the effects of the coronavirus have been exaggerated to hurt Trump. This theory finds considerably more support among Republicans than Democrats, for two reasons: Republicans have much to lose in a presidential election year, and Trump and other right-wing elites have explicitly peddled the idea that COVID-19 has been exaggerated to hurt him.

The second major causal factor behind conspiracy theories is “conspiracy thinking”—a worldview that predisposes people to interpret events and information as the product of shadowy conspiracies. When activated—by information suggesting a conspiracy, or by the rhetoric of political elites, or by the anxiety brought on by an uncontrollable disaster—this latent predisposition makes conspiracies an attractive explanation for undesirable circumstances. In our poll, we measured conspiracy thinking by asking respondents to react to statements such as “The people who really ‘run’ the country, are not known to the voters.” We find that respondents who agree with sentiments such as this tend to believe more conspiracy theories, more deeply. In fact, our measure of conspiracy thinking strongly predicts beliefs in every one of the 22 specific conspiracy theories we asked respondents about. On the one hand, it’s troubling that some people so easily adopt conspiracy beliefs. On the other, many people don’t—and these people act as a firewall to the spread of conspiracy theories, giving most a natural ceiling.

Read: A new statistic reveals why America’s COVID-19 numbers are flat

Conspiracy thinking is most predictive of beliefs in specific conspiracy theories when partisan leaders don’t stake out positions, and least predictive when they do. Republican leaders have, for example, long questioned the reality of climate change, going so far as to call it a hoax. In this case, Republicanism is almost as predictive as conspiracy thinking in explaining climate-change denial. But this is not the case for conspiracy theories that have not been pulled into the political fray, such as those about AIDS, vaccines, and genetically modified foods. Should theories such as these become fodder for popular political and ideological leaders, the beliefs in them could increase rather quickly.

Under this framework, the structure of COVID-19 conspiracy theories—how widespread they are, where they come from, and what they might mean—is completely predictable. The key difference in the case of the coronavirus is the stakes. We have little reason to be concerned, for example, about the one in three Americans who thinks aliens have secretly made contact with humans. And at no point was our society in danger because nearly 80 percent of Americans once thought the Warren Commission got the details of John F. Kennedy’s assassination wrong. But the consequences of blaming the coronavirus’s emergence on the wrong source, or of doubting its seriousness, could be life-threatening on a massive scale. People who believe that the virus is a bioweapon may be more likely to engage in hoarding and other self-centered behaviors. And if the one in three Americans who believes that the effects of COVID-19 have been exaggerated choose to forgo crucial health practices, such as social distancing, frequent hand-washing, and wearing a mask, then the disease could spread faster and farther than otherwise, and could cost many thousands of lives.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.